Jimmy Doolittle

James Doolittle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | James Harold Doolittle |

| Nickname(s) | "Jimmy" |

| Born | December 14, 1896 Alameda, California |

| Died | September 27, 1993 (aged 96) Pebble Beach, California |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1917–1959 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Twelfth Air Force Fifteenth Air Force Eighth Air Force |

| Battles / wars | Mexican Border Service World War I (stateside duty) World War II

|

| Awards | Medal of Honor Army Distinguished Service Medal-2 Silver Star Distinguished Flying Cross-3 Bronze Star Air Medal-4 Presidential Medal of Freedom |

| Spouse(s) |

Josephine Daniels

(m. 1917; died 1988) |

| Other work | Shell Oil, VP, director Space Technology Laboratories, chairman |

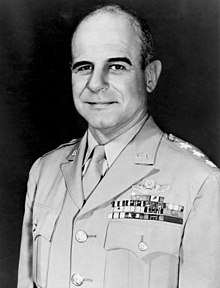

James Harold Doolittle (December 14, 1896 – September 27, 1993) was an American General and aviation pioneer. He made early coast-to-coast flights, earned a doctorate from M.I.T. in aeronautics, won many flying races and most significantly, helped develop instrument flying.

A flying instructor during World War I and later a Reserve officer in the United States Army Air Corps, Doolittle was recalled to active duty during World War II. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for personal valor and leadership as commander of the Doolittle Raid, a bold long-range retaliatory air raid on the Japanese main islands, on April 18, 1942, four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The attack was a major morale booster for the United States, and Doolittle was celebrated as a hero.

He was eventually promoted to Lieutenant general and commanded the Twelfth Air Force over North Africa, the Fifteenth Air Force over the Mediterranean, and the Eighth Air Force over Europe. After WWII he left the Air Force but remained active in many technical fields, and was eventually promoted to general (4-star) years after retirement.[1]

Early life and education

Doolittle was born in Alameda, California, and spent his youth in Nome, Alaska, where he earned a reputation as a boxer. His parents were Frank Henry Doolittle and Rosa (Rose) Cerenah Shephard. By 1910, Jimmy Doolittle was attending school in Los Angeles. When his school attended the 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field, Doolittle saw his first airplane.[2] He attended Los Angeles City College after graduating from Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, and later won admission to the University of California, Berkeley where he studied in The School of Mines. He was a member of Theta Kappa Nu fraternity, which would merge into Lambda Chi Alpha during the latter stages of the Great Depression.

Doolittle took a leave of absence in October 1917 to enlist in the Signal Corps Reserve as a flying cadet; he ground trained at the School of Military Aeronautics (an Army school) on the campus of the University of California, and flight-trained at Rockwell Field, California. Doolittle received his Reserve Military Aviator rating and was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Signal Officers Reserve Corps of the U.S. Army on March 11, 1918.

Military career

During World War I, Doolittle stayed in the United States as a flight instructor and performed his war service at Camp John Dick Aviation Concentration Center ("Camp Dick"), Texas; Wright Field, Ohio; Gerstner Field, Louisiana; Rockwell Field, California; Kelly Field, Texas and Eagle Pass, Texas.

Doolittle's service at Rockwell Field consisted of duty as a flight leader and gunnery instructor. At Kelly Field, he served with the 104th Aero Squadron and with the 90th Aero Squadron of the 1st Surveillance Group. His detachment of the 90th Aero Squadron was based at Eagle Pass, patrolling the Mexican border. Recommended by three officers for retention in the Air Service during demobilization at the end of the war, Doolittle qualified by examination and received a Regular Army commission as a 1st Lieutenant, Air Service, on July 1, 1920.

On May 10, 1921, he was engineering officer and pilot for an expedition recovering a plane that had force-landed in a Mexican canyon on February 10 during a transcontinental flight attempt by Lieut. Alexander Pearson. Doolittle reached the plane on May 3 and found it serviceable, then returned May 8 with a replacement motor and four mechanics. The oil pressure of the new motor was inadequate and Doolittle requested two pressure gauges, using carrier pigeons to communicate. The additional parts were dropped by air and installed, and Doolittle flew the plane to Del Rio, Texas himself, taking off from a 400-yard airstrip hacked out of the canyon floor.

Subsequently, he attended the Air Service Mechanical School at Kelly Field and the Aeronautical Engineering Course at McCook Field, Ohio. Having at last returned to complete his college degree, he earned a Bachelor of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley in 1922, and joined the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity.

Doolittle was one of the most famous pilots during the inter-war period. In September 1922, he made the first of many pioneering flights, flying a de Havilland DH-4 – which was equipped with early navigational instruments – in the first cross-country flight, from Pablo Beach (now Jacksonville Beach), Florida, to Rockwell Field, San Diego, California, in 21 hours and 19 minutes, making only one refueling stop at Kelly Field. The U.S. Army awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Within days after the transcontinental flight, he was at the Air Service Engineering School (a precursor to the Air Force Institute of Technology) at McCook Field, Dayton, Ohio. For Doolittle, the school assignment had special significance: "In the early '20s, there was not complete support between the flyers and the engineers. The pilots thought the engineers were a group of people who zipped slide rules back and forth, came out with erroneous results and bad aircraft; and the engineers thought the pilots were crazy – otherwise they wouldn't be pilots. So some of us who had previous engineering training were sent to the engineering school at old McCook Field. ... After a year's training there in practical aeronautical engineering, some of us were sent on to MIT where we took advanced degrees in aeronautical engineering. I believe that the purpose was served, that there was thereafter a better understanding between pilots and engineers."

In July 1923, after serving as a test pilot and aeronautical engineer at McCook Field, Doolittle entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In March 1924, he conducted aircraft acceleration tests at McCook Field, which became the basis of his master's thesis and led to his second Distinguished Flying Cross. He received his S.M. in Aeronautics from MIT in June 1924. Because the Army had given him two years to get his degree and he had done it in just one, he immediately started working on his Sc.D. in Aeronautics, which he received in June 1925. His doctorate in aeronautical engineering was the first ever issued in the United States.[3] He said that he considered his master's work more significant than his doctorate.

Following graduation, Doolittle attended special training in high-speed seaplanes at Naval Air Station Anacostia in Washington, D.C.. He also served with the Naval Test Board at Mitchel Field, Long Island, New York, and was a familiar figure in air speed record attempts in the New York area. He won the Schneider Cup race in a Curtiss R3C in 1925 with an average speed of 232 MPH.[4] For that feat, Doolittle was awarded the Mackay Trophy in 1926.

In April 1926, Doolittle was given a leave of absence to go to South America to perform demonstration flights. In Chile, he broke both ankles, but put his P-1 Hawk through aerial maneuvers with his ankles in casts. He returned to the United States, and was confined to Walter Reed Army Hospital for his injuries until April 1927. Doolittle was then assigned to McCook Field for experimental work, with additional duty as an instructor pilot to the 385th Bomb Squadron of the Air Corps Reserve. During this time, in 1927 he was the first to perform an outside loop, previously thought to be a fatal maneuver. Carried out in a Curtiss fighter at Wright Field in Ohio, Doolittle executed the dive from 10,000 feet, reached 280 miles per hour, bottomed out upside down, then climbed and completed the loop.

Instrument flight

Doolittle's most important contribution to aeronautical technology were his early contributions to instrument flying. He was the first to recognize that true operational freedom in the air could not be achieved unless pilots developed the ability to control and navigate aircraft in flight, from takeoff run to landing rollout, regardless of the range of vision from the cockpit. Doolittle was the first to envision that a pilot could be trained to use instruments to fly through fog, clouds, precipitation of all forms, darkness, or any other impediment to visibility; and in spite of the pilot's own possibly convoluted motion sense inputs. Even at this early stage, the ability to control aircraft was getting beyond the motion sense capability of the pilot. That is, as aircraft became faster and more maneuverable, pilots could become seriously disoriented without visual cues from outside the cockpit, because aircraft could move in ways that pilots' senses could not accurately decipher.

Doolittle was also the first to recognize these psycho-physiological limitations of the human senses (particularly the motion sense inputs, i.e., up, down, left, right). He initiated the study of the subtle interrelationships between the psychological effects of visual cues and motion senses. His research resulted in programs that trained pilots to read and understand navigational instruments. A pilot learned to "trust his instruments," not his senses, as visual cues and his motion sense inputs (what he sensed and "felt") could be incorrect or unreliable.

In 1929, he became the first pilot to take off, fly and land an airplane using instruments alone, without a view outside the cockpit. Having returned to Mitchel Field that September, he assisted in the development of fog flying equipment. He helped develop, and was then the first to test, the now universally used artificial horizon and directional gyroscope. He attracted wide newspaper attention with this feat of "blind" flying and later received the Harmon Trophy for conducting the experiments. These accomplishments made all-weather airline operations practical.

Reserve status

In January 1930, he advised the Army on the construction of Floyd Bennett Field in New York City. Doolittle resigned his regular commission on February 15, 1930, and was commissioned a Major in the Air Reserve Corps a month later, being named manager of the Aviation Department of Shell Oil Company, in which capacity he conducted numerous aviation tests.[5] While in the Reserve, he also returned to temporary active duty with the Army frequently to conduct tests.

Doolittle helped influence Shell Oil Company to produce the first quantities of 100 octane aviation gasoline. High octane fuel was crucial to the high-performance planes that were developed in the late 1930s.

In 1931, Doolittle won the first Bendix Trophy race from Burbank, California, to Cleveland, in a Laird Super Solution biplane.

In 1932, Doolittle set the world's high speed record for land planes at 296 miles per hour in the Shell Speed Dash. Later, he took the Thompson Trophy race at Cleveland in the notorious Gee Bee R-1 racer with a speed averaging 252 miles per hour. After having won the three big air racing trophies of the time, the Schneider, Bendix, and Thompson, he officially retired from air racing stating, "I have yet to hear anyone engaged in this work dying of old age."

In April 1934, Doolittle was selected to be a member of the Baker Board. Chaired by former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, the board was convened during the Air Mail scandal to study Air Corps organization. In 1940, he became president of the Institute of Aeronautical Science.

Doolittle returned to active duty in the U.S. Army Air Corps on July 1, 1940 with rank of Major. He was assigned as the assistant district supervisor of the Central Air Corps Procurement District at Indianapolis, and Detroit, where he worked with large auto manufacturers on the conversion of their plants for production of planes.[6] The following August, he went to England as a member of a special mission and brought back information about other countries' air forces and military build-ups.

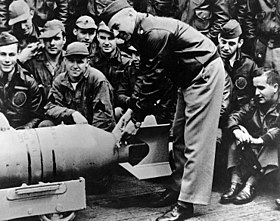

Doolittle Raid

Following the reorganization of the Army Air Corps into the USAAF in June 1941, Doolittle was promoted to lieutenant colonel on January 2, 1942, and assigned to Army Air Forces Headquarters to plan the first retaliatory air raid on the Japanese homeland. He volunteered for and received General H.H. Arnold's approval to lead the top secret attack of 16 B-25 medium bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, with targets in Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama, Osaka and Nagoya.

After training at Eglin Field and Wagner Field in northwest Florida, Doolittle, his aircraft and volunteer flight crews proceeded to McClellan Field, California for aircraft modifications at the Sacramento Air Depot, followed by a short final flight to Naval Air Station Alameda, California for embarkation aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. On April 18, Doolittle and his 16 B-25 crews took off from the Hornet, reached Japan, and bombed their targets. Fifteen of the planes then headed for their recovery airfield in China, while one crew chose to land in Russia due to their bomber's unusually high fuel consumption. As did most of the other crewmen who participated in the one-way mission, Doolittle and his crew bailed out safely over China when their B-25 ran out of fuel. By then, they had been flying for about 12 hours, it was nighttime, the weather was stormy, and Doolittle was unable to locate their landing field. Doolittle came down in a rice paddy (saving a previously injured ankle from breaking) near Chuchow (Quzhou). He and his crew linked up after the bailout and were helped through Japanese lines by Chinese guerrillas and American missionary John Birch. Other aircrews were not so fortunate, although most eventually reached safety with the help of friendly Chinese. Seven crew members lost their lives, four as a result of being captured and murdered by the Japanese and three due to an aircraft crash or while parachuting. Doolittle thought he would be court martialed due to having to launch the raid ahead of schedule after being spotted by Japanese patrol boats.

Doolittle went on to fly more combat missions as commander of the 12th Air Force in North Africa, for which he was awarded four Air Medals. The other surviving members of the Doolittle raid also went on to new assignments.

Doolittle received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House for planning and leading his raid on Japan. His citation reads: "For conspicuous leadership above and beyond the call of duty, involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life. With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Lt. Col. Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland."

The Doolittle Raid is viewed by historians as a major morale-building victory for the United States. Although the damage done to Japanese war industry was minor, the raid showed the Japanese that their homeland was vulnerable to air attack, and forced them to withdraw several front-line fighter units from Pacific war zones for homeland defense. More significantly, Japanese commanders considered the raid deeply embarrassing, and their attempt to close the perceived gap in their Pacific defense perimeter led directly to the decisive American victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942.

When asked from where the Tokyo raid was launched, President Roosevelt coyly said its base was Shangri-La, a fictional paradise from the popular novel Lost Horizon. In the same vein, the U.S. Navy named one of its Essex-class fleet carriers the USS Shangri-La.

World War II, post-raid

In July 1942, as a brigadier general—he had been promoted by two grades on the day after the Tokyo attack, bypassing the rank of full colonel—Doolittle was assigned to the nascent Eighth Air Force. This followed his rejection by General Douglas MacArthur as commander of the South West Pacific Area to replace Major General George Brett. Major General Frank Andrews first turned down the position, and, offered a choice between George Kenney and Doolittle, MacArthur chose Kenney.[7] In September, Doolittle became commanding general of the Twelfth Air Force, soon to be operating in North Africa. He was promoted to major general in November 1942, and in March 1943 became commanding general of the Northwest African Strategic Air Force, a unified command of U.S. Army Air Force and Royal Air Force units. In September, he commanded a raid against the Italian town of Battipaglia that was so thorough in its destruction that General Carl Andrew Spaatz sent him a joking message: "You're slipping Jimmy. There's one crabapple tree and one stable still standing."[8]

Maj. Gen. Doolittle took command of the Fifteenth Air Force in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in November 1943. On June 10, he flew as co-pilot with Jack Sims, fellow Tokyo Raider, in a B-26 Marauder of the 320th Bombardment Group, 442nd Bombardment Squadron on a mission to attack gun emplacements at Pantelleria. Doolittle continued to fly, despite the risk of capture, while being privy to the Ultra secret, which was that the German encryption systems had been broken by the British.[9] From January 1944 to September 1945, he held his largest command, the Eighth Air Force (8 AF) in England as a lieutenant general, his promotion date being March 13, 1944 and the highest rank ever held by an active reserve officer in modern times.

Doolittle's breakthrough in fighter tactics

Doolittle's major influence on the European air war occurred early in 1943 when he changed the policy requiring escorting fighters to remain with their bombers at all times. Doolittle allowed American fighter escorts to fly far ahead of the bombers' combat box formations in air supremacy mode. Throughout most of 1944 this tactic negated the effectiveness of the twin-engined Zerstörergeschwader heavy fighter wings (and their replacement, single-engined Sturmgruppen of heavily armed Fw 190As) by clearing opposition of the Luftwaffe's bomber destroyers from the airspace ahead of the bomber formations on their way to their targets. After the bombers had hit their targets, the USAAF's fighters were then free to strafe German airfields and transport on their trips returning to base.

These tasks were initially performed with Lockheed P-38 Lightnings and Republic P-47 Thunderbolts through the end of 1943. These were progressively replaced with the long-ranged North American P-51 Mustangs as the spring of 1944 wore on.

Post-VE Day

After the end of the European war, the Eighth Air Force was re-equipped with B-29 Superfortress bombers and started to relocate to Okinawa in the Pacific. Two bomb groups had begun to arrive on August 7. However, the 8th was not scheduled to be at full strength until February 1946 and Doolittle declined to rush 8th Air Force units into combat saying that "If the war is over, I will not risk one airplane nor a single bomber crew member just to be able to say the 8th Air Force had operated against the Japanese in the Pacific".

Postwar

Doolittle Board

On 27 March 1946, Doolittle was requested by Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson to head a commission on the relationships between officers and enlisted men in the U.S. Army. Called the "Doolittle Board", or informally the "GI Gripes Board", many of the recommendations were implemented for the postwar volunteer U.S. Army,[10] though many professional officers and noncommissioned officers thought the Board "destroyed the discipline of the Army".[11] After the Korean War, columnist Hanson Baldwin said the Doolittle Board "caused severe damage to service effectiveness by recommendations intended to 'democratize' the Army—a concept that is self-contradictory".[12]

U.S. space program

Doolittle became acquainted with the field of space science in its infancy. He wrote in his autobiography, "I became interested in rocket development in the 1930s when I met Robert H. Goddard, who laid the foundation [in the US]. ... While with Shell [Oil] I worked with him on the development of a type of [rocket] fuel. ... "[13] Harry Guggenheim, whose foundation sponsored Goddard's work, and Charles Lindbergh, who encouraged Goddard's efforts, arranged for (then Major) Doolittle to discuss with Goddard a special blend of gasoline. Doolittle piloted himself to Roswell, New Mexico in October 1938 and was given a tour of Goddard's workshop and a "short course" in rocketry and space travel. He then wrote a memo, including a rather detailed description of Goddard's rocket. In closing he said, "interplanetary transportation is probably a dream of the very distant future, but with the moon only a quarter of a million miles away—who knows!"[14] In July 1941 he wrote Goddard that he was still interested in rocket propulsion research. The Army, however, was interested only in JATO at this point. Doolittle was concerned about the state of rocketry in the US and remained in touch with Goddard.[14]: 1443

Shortly after World War II, Doolittle spoke to an American Rocket Society conference at which a large number interested in rocketry attended. The topic was Robert Goddard's work. He later stated that at that time "... we [the aeronautics field in the US] had not given much credence to the tremendous potential of rocketry.[15]

In 1956, he was appointed chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) because the previous chairman, Jerome C. Hunsaker, thought Doolittle to be more sympathetic to the rocket, which was increasing in importance as a scientific tool as well as a weapon.[13]: 516 The NACA Special Committee on Space Technology was organized in January 1958 and chaired by Guy Stever to determine the requirements of a national space program and what additions were needed to NACA technology. Doolittle, Dr. Hugh Dryden and Stever selected committee members, such as Dr. Wernher von Braun from the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, Sam Hoffman of Rocketdyne, Abe Hyatt of the Office of Naval Research and Colonel Norman Appold from the USAF missile program, considering their potential contributions to US space programs and ability to educate NACA people in space science.[16]

Reserve status

On 5 January 1946, Doolittle reverted to inactive reserve status in the Army Air Forces in the grade of lieutenant general, a rarity in those days when nearly all other reserve officers were limited to the rank of major general or rear admiral, a restriction that would not end in the US armed forces until the 21st century. He retired from the United States Army on 10 May 1946. On 18 September 1947, his reserve commission as a general officer was transferred to the newly established United States Air Force. Doolittle returned to Shell Oil as a vice president, and later as a director.

In the summer of 1946, Doolittle went to Stockholm where he was consulted about the "ghost rockets" that had been observed over Scandinavia.[17]

In 1947, Doolittle also became the first president of the Air Force Association, an organization which he helped create.

In 1948, Doolittle advocated the desegregation of the US military. "I am convinced", emphasized Doolittle, "that the solution to the situation is to forget that they are colored." Industry was in the process of integrating, Doolittle said, "and it is going to be forced on the military. You are merely postponing the inevitable and you might as well take it gracefully."[18]

In March 1951, Doolittle was appointed a special assistant to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, serving as a civilian in scientific matters which led to Air Force ballistic missile and space programs. In 1952, following a string of three air crashes in two months at Elizabeth, New Jersey, the President of the United States, Harry S. Truman, appointed him to lead a presidential commission examining the safety of urban airports. The report "Airports and Their Neighbors" led to zoning requirements for buildings near approaches, early noise control requirements, and initial work on "super airports" with 10,000 ft runways, suited to 150 ton aircraft.

Doolittle was appointed a life member of the MIT Corporation, the university's board of trustees, an uncommon permanent appointment, and served as an MIT Corporation Member for 40 years.[19]

In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Doolittle to perform a study of the Central Intelligence Agency; The resulting work was known as the Doolittle Report, 1954, and was classified for a number of years.

In January 1956, Eisenhower asked Doolittle to serve as a member on the first edition of the President's Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities which, years later, would become known as the President's Intelligence Advisory Board.[citation needed]

From 1957 to 1958, he was chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). This period was during the events of Sputnik, Vanguard and Explorer. He was the last person to hold this position, as the NACA was superseded by NASA. Doolittle was offered the job of being the first administrator of NASA, but he turned it down.[20]

Doolittle retired from Air Force Reserve duty on February 28, 1959. He remained active in other capacities, including chairman of the board of TRW Space Technology Laboratories.

In 1972, Doolittle received the Tony Jannus Award for his distinguished contributions to commercial aviation, in recognition of the development of instrument flight.

On April 4, 1985, the U.S. Congress promoted Doolittle to the rank of full four-star general (O-10) on the U.S. Air Force retired list. In a later ceremony, President Ronald Reagan and U.S. Senator and retired Air Force Reserve Major General Barry Goldwater pinned on Doolittle's four-star insignia.

In addition to his Medal of Honor for the Tokyo raid, Doolittle received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, two Distinguished Service Medals, the Silver Star, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star Medal, four Air Medals, and decorations from Belgium, China, Ecuador, France, Great Britain, and Poland. He was the first American to be awarded both the Medal of Honor and the Medal of Freedom. Doolittle also was awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 1959.[21] In 1983, he was awarded the United States Military Academy's Sylvanus Thayer Award. He was inducted in the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America as the only member of the air racing category in the inaugural class of 1989, and into the Aerospace Walk of Honor in the inaugural class of 1990. The headquarters of the United States Air Force Academy Association of Graduates (AOG) on the grounds of the United States Air Force Academy is named Doolittle Hall.

On May 9, 2007, The new 12th Air Force Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC), Building 74, at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, was named in his honor as the "General James H. Doolittle Center". Several surviving members of the Doolittle Raid were in attendance during the ribbon cutting ceremony.

Personal life

Doolittle married Josephine "Jo" E. Daniels on December 24, 1917. At a dinner celebration after Jimmy Doolittle's first all-instrument flight in 1929, Josephine Doolittle asked her guests to sign her white damask tablecloth. Later, she embroidered the names in black. She continued this tradition, collecting hundreds of signatures from the aviation world. The tablecloth was donated to the Smithsonian Institution. Married for over 70 years, Josephine Doolittle died in 1988, five years before her husband.

The Doolittles had two sons, James Jr., and John. Both became military officers and pilots. James Jr. was an A-26 Invader pilot in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II and later a fighter pilot in the U.S. Air Force in the late 1940s through the late 1950s. He committed suicide at the age of thirty-eight in 1958.[22] At the time of his death, James Jr. was a Major and commander of the 524th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, piloting the F-101 Voodoo.[23]

His other son, John P. Doolittle, retired from the Air Force as a Colonel, and his grandson, Colonel James H. Doolittle III, was the vice commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle died at the age of 96 in Pebble Beach, California on September 27, 1993, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, near Washington, D.C., next to his wife.[24] In his honor at the funeral, there was also a flyover of Miss Mitchell, a lone B-25 Mitchell, and USAF Eighth Air Force bombers from Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. After a brief graveside service, fellow Doolittle Raider Bill Bower began the final tribute on the bugle. When emotion took over, Doolittle's great-grandson, Paul Dean Crane, Jr., played Taps.[25]

Doolittle was initiated to the Scottish Rite Freemasonry,[26][27] where he took the 33rd degree,[28][29] becoming also a Shriner.[30]

Dates of military rank

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Private First Class | United States Army | November 10, 1917 |

| No insignia | Aviation Cadet | United States Army | October 6, 1917 |

| Second Lieutenant | Officers Reserve Corps | March 11, 1918 | |

| Second Lieutenant | U.S. Army Air Service | September 19, 1920 | |

| First Lieutenant | U.S. Army Air Service | March 17, 1921 Resigned February 15, 1930 | |

| Major | Specialist Reserve | March 5, 1930 | |

| Major | Army of the United States | July 1, 1940 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Army of the United States | January 2, 1942 | |

| Brigadier General | Army of the United States | April 19, 1942 | |

| Major General | Army of the United States | November 20, 1942 | |

| Lieutenant General | Army of the United States | March 13, 1944 | |

| Lieutenant General | U.S. Army, Retired | January 5, 1946 | |

| Lieutenant General | Army Reserve | May 10, 1946 | |

| Lieutenant General | Air Force Reserve | September 18, 1947 | |

| Lieutenant General | Air Force Reserve, Retired List | February 28, 1959 | |

| General | Air Force Reserve, Retired List | April 4, 1985 |

Military and civilian awards

Doolittle's military and civilian decorations include the following:

|

United States Air Force Command Pilot Badge |

|

Honorary Naval Aviator Badge |

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and organization: Brigadier General, U.S. Army Air Corps

Place and date: Over Japan

Entered service at: Berkley, Calif.

Birth: Alameda, Calif.

G.O. No.: 29, 9 June 1942

Citation:

For conspicuous leadership above the call of duty, involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life. With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Gen. Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland.[32]

Other awards and honors

Doolittle also received the following awards and honors:

- Awards

- In 1972, he was awarded the Horatio Alger Award, which is given to those who are dedicated community leaders who demonstrate individual initiative and a commitment to excellence; as exemplified by remarkable achievements accomplished through honesty, hard work, self-reliance and perseverance over adversity. The Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans, Inc. bears the name of the renowned author Horatio Alger, Jr., whose tales of overcoming adversity through unyielding perseverance and basic moral principles captivated the public in the late 19th century.[33]

- On December 11, 1981, Doolittle was awarded Honorary Naval Aviator wings in recognition of his many years of support of military aviation by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Thomas B. Hayward.[34]

- In 1983, Doolittle was awarded the Sylvanus Thayer Award.

- Honors

- The city of Doolittle, Missouri, located 5 miles west of Rolla was named in his honor after World War II.

- Doolittle was invested into the Sovereign Order of Cyprus and his medallion is now on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

- His Bolivian Order of the Condor of the Andes is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.[35]

- In 1967, James H. Doolittle was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

- Flying magazine ranked him 6th on its list of the 51 Heroes of Aviation.[36]

- The Society of Experimental Test Pilots annually presents the James H. Doolittle Award in his memory. The award is for "outstanding accomplishment in technical management or engineering achievement in aerospace technology".

- Inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum in 1966.[37]

- The oldest residence hall on Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University's campus, Doolittle Hall (1968), was named after General James Harold "Jimmy" Doolittle.

In popular culture

- Spencer Tracy played Doolittle in Mervyn LeRoy's 1944 film Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. This portrayal has received much praise.

- Alec Baldwin played Doolittle in Michael Bay's 2001 film Pearl Harbor.

- Bob Clampett's 1946 cartoon Baby Bottleneck briefly portrays a dog named "Jimmy Do-quite-a-little", who invents a failed rocketship.

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ "Jimmy Doolittle Given Fourth Star by Reagan". Associated Press. June 14, 1985 – via LA Times.

- ^ Berliner 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Quigley, Samantha L. "Detroit Defied Reality to Help Win World War II". United Service Organizations. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Flight October 29, 1925, p.703.

- ^ Donald M. Pattillo. A History in the Making: 80 Turbulent Years in the American General Aviation Industry. p. 16.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 114, 219-22, 239, 279, Random House, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ Wolk 2003, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Antony Beevor (2012). The Second World War. p. 503. ISBN 978-0-7538-2824-3.

- ^ G. H. Spaulding, CAPT, USN (Ret). "Enigmatic Man". Retrieved November 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ p. 154 Brown, Jerold E. Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Army Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001

- ^ p. 105 Zellers, Larry In Enemy Hands: A Prisoner in North Korea University Press of Kentucky, 1 Nov 1999

- ^ p. 51 Bogle, Lori L. The Pentagon's Battle for the American Mind: The Early Cold War Texas A&M University Press, 12 Oct 2004

- ^ a b Doolittle, General James H. "Jimmy" with Carroll V. Glines (1991). I Could Never Be So Lucky Again. New York: Bantam Books. p. 515.

- ^ a b Goddard, Esther and G. Edward Pendray, eds. (1970). The Papers of Robert H. Goddard, 3 vols. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 1208–16.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Putnam, William D. and Eugene M. Emme. "I Was There: "The Tremendous Potential of Rocketry" AIR & SPACE Magazine". www.airspacemag.com/space. Smithsonian Institution (Sep 2012).

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Bilstein, Roger E. (1980). Stages to Saturn. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 34.

- ^ John Keel (1996). Operation Trojan Horse (PDF). p. 122. ISBN 978-0962653469. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 20, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wolk, Herman S. (1998). "When the Color Line Ended". Air Force Magazine. 81 (7).

- ^ "Members of the MIT Corporation". mit.edu.

- ^ Putnam, William D. and Eugene M. Emme (September 2012). "I Was There: "The Tremendous Potential of Rocketry"." AIR & SPACE Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Public Welfare Award". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rife, Susan L. (July 20, 2006). "My grandfather The General". Herald Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ "Lewiston Evening Journal - Google News Archive Search". google.com.

- ^ "Jimmy Doolittle". Claim to Fame: Medal of Honor recipients. Find a Grave. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ "Post Mortem - Bill Bower dies; Doolittle Raider was last surviving pilot". washingtonpost.com.

- ^ "Famous masons". Dalhousie Lodge F. & A.M., Newtonville, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "List of notable freemasons". freemasonry.bcy.ca. Archived from the original on October 4, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Celebrating More Than 100 Years of Freemasonry: Famous Masons in History". Matawan Lodhe N0 192 F&AM, New Jersey. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

Jimmy Doolittle, 33°, Grand Cross.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gallery of famous masons". mastermason.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "James Harold "Jimmy" Doolittle Passes Away". masonrytoday.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

with special dispensation from the Grand Lodge of California and the Grand Lodge of Louisiana, Doolittle was given all three degrees on August 16th, 1918 in Lake Charles Lodge No. 16.

- ^ Official Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Army, 1926. pg. 165.

- ^ "World War II (A-F); Doolittle, Jimmy entry". Medal of Honor recipients. United States Army Center of Military History. August 3, 2009. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Horatio Alger Association Member Information". Horatioalger.org. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Honorary Naval Aviator Designations" (PDF). U.S. Navy History Office. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Go Flight". National Air and Space Museum. June 23, 2016.

- ^ "51 Heroes of Aviation". Flying Magazine.

- ^ "San Diego Air & Space Museum - Historical Balboa Park, San Diego". sandiegoairandspace.org.

- Bibliography

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Berliner, Don (December 2009 – January 2010). "The Big Race of 1910". Air & Space. 24 (6): 34–39.

- James H. Doolittle; Carroll V. Glines. I Could Never Be So Lucky Again. ISBN 0-88740-737-4. OCLC 33957079.

- Carroll V. Glines (1972). Jimmy Doolittle: Daredevil Aviator and Scientist. Macmillan. OCLC 488509.

- Jonna Doolittle Hoppes. Calculated Risk. ISBN 1-891661-44-2.

- "The 1925 Schneider Trophy Race". Flight. London: 703. October 29, 1925.

- Wolk, Herman S. (2003). Fulcrum of Power: Essays on the United States Air Force and National Security (PDF). Washington, D. C.: Air Force History and Museums Program. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - SSG Cornelius Seon (Retired) (adapted public domain text). "United States Air Force". Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- "Arlington National Cemetery Website – James Harold Doolittle". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- "Travis Air Museum, supporting the Jimmy Doolittle Air & Space Museum". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- "Maritimequest Doolittle Raid Photo Gallery". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- William R. Wilson. "Article: Jimmy Doolittle Reminiscences About World War II". Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Medal of Honor recipients on film". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- "Interview with granddaughter Joanna Doolittle Hoppes at the Pritzker Military Library". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- "DoolittleRaiders.com". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- Media

- The short film 15 AF HERITAGE – HIGH STRATEGY – BOMBER AND TANKERS TEAM (1980) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film ACTIVITIES OF THE U.S. ARMY AIR SERVICE (1925) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- "Doolittle Tames the Gee Bee" Story of the 1932 Thompson Trophy race. Includes quotes, photos, video

- 1896 births

- 1993 deaths

- Air Corps Tactical School alumni

- American air racers

- American military personnel of World War I

- American test pilots

- United States Army Air Forces Medal of Honor recipients

- Aviators from California

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Doolittle Raiders

- Flight instructors

- Harmon Trophy winners

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath

- Mackay Trophy winners

- Recipients of awards from the United States National Academy of Sciences

- People from Alameda, California

- People from Nome, Alaska

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Recipients of the Order of the Condor of the Andes

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Schneider Trophy pilots

- University of California, Berkeley College of Engineering alumni

- United States Army Air Forces generals

- United States Army Air Service pilots of World War I

- United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II

- American World War II bomber pilots

- Chief Scientists of the United States Air Force

- Motorsports Hall of Fame of America inductees

- World War II recipients of the Medal of Honor

- People from Pebble Beach, California

- American aviation record holders

- Aerobatic record holders