Breast

The term breast, also known by the Latin mamma in anatomy, refers to the upper ventral region of an animal's torso, particularly that of mammals, including human beings. In addition, the breasts are parts of a female mammal's body which contain the organs that secrete milk used to feed infants. This article focuses on human female breasts, but it should be noted that male humans also have breasts (although usually less prominent) that are structurally identical and homologous to the female, as they develop embryologically from the same tissues. In some situations male breast development does occur, a condition called gynecomastia.

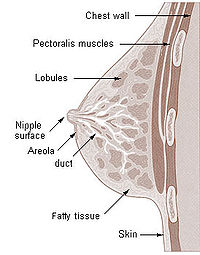

Anatomy of the female breasts

The breasts are covered by skin; each breast has one nipple surrounded by the areola. The areola is colored from pink to dark brown, hairless, and has several sebaceous glands. The larger mammary glands within the breast produce the milk; they consist of several lobules, and each breast has some 10-20 lactiferous ducts that drain milk from the lobules to the nipple, where each duct has its own opening.

Most of the breast is connective tissue, i.e., adipose tissue (fat) and Cooper's ligaments, rather than the mammary glands. The breasts sit over the pectoralis major muscle and usually extend from the level of the 2nd rib to the level of the 6th rib anteriorly. The superior lateral quadrant of the breast extends diagonally upwards in an 'axillary tail'. A thin layer of mammary tissue extends from the clavicle above to the seventh or eighth ribs below and from the midline to the edge of the latissimus dorsi posteriorly.

The arterial blood supply to the breasts is derived from the internal thoracic artery (previously referred to as the internal mammary artery), lateral thoracic artery, thoracoacromial artery, and posterior intercostal arteries. The venous drainage of the breast is mainly to the axillary vein, but there is some drainage to the internal thoracic vein and the intercostal veins. Both sexes have a large concentration of blood vessels and nerves in their nipples.

The breast is innervated by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the 4th through 6th intercostal nerves. The nipple is supplied by the T4 dermatome.

The primary anatomical support for the breasts is thought to be provided by the Cooper's ligaments, with additional support from the skin covering the breasts themselves, and it is this support which determines the shape of the breasts. In a small fraction of women, the frontal milk sinuses (ampulla) in the breasts are not flush with the surrounding breast tissue, which causes the sinus area to visibly bulge outward.

Lymphatic drainage

About 75% of lymph from the breast travels to the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes. The rest travels to parasternal nodes, to the other breast, or abdominal lymph nodes. The axillary nodes include the pectoral, subscapular, and humeral groups of lymph nodes. These drain to the central axillary lymph nodes, then to the apical axillary lymph nodes. The lymphatic drainage of the breasts is particularly relevant to oncology, since cancer cells can break away from a tumour (breast cancer being a common cancer), and spread to other parts of the body through the lymph system by a process known as metastasis.

Function

Breastfeeding and pregnancy

The function of the mammary glands in female breasts is to nurture the young by producing milk, which is secreted by the nipples during lactation. While the mammary glands that produce milk are present in the male, they normally remain undeveloped. The orb-like shape of breasts may help limit heat loss, as a fairly high temperature is required for the production of milk.

Milk production can also occur in both men and women as an adverse effect of some medicinal drugs (such as some antipsychotic medication), extreme physical stress or in endocrine disorders. Oftentimes, newborn babies are capable of lactation because they receive some amount of prolactin and oxytocin (milk hormones) from their connection to the mother.

Although the secretion of milk is the function of the mammary glands, these actually make up a relatively small fraction of the overall breast tissue. It is commonly assumed by biologists that the real evolutionary purpose of women having breasts is to attract the male of the species; that, in other words, breasts are sexually dimorphic, or secondary sex characteristics.

Others believe that the human breast evolved in order to prevent infants from suffocating while feeding[2]. Since human infants do not have a protruding jaw like our ancestors and the other primates, the infant's nose might be blocked by a flat female chest while feeding. According to this theory, as the human jaw became recessed, the breasts became larger to compensate.

Other suggested functions

Zoologists point out that no female mammal other than the human has breasts of comparable size when not lactating and that humans are the only primate that have permanently swollen breasts. This suggests that the external form of the breasts is connected to factors other than lactation alone.

One theory is based around the fact that, unlike nearly all other primates, human females do not display clear, physical signs of ovulation.This could have plausibly resulted in human males evolving to respond to more subtle signs of ovulation. During ovulation, the increased estrogen present in the female body results in a slight swelling of the breasts, which then males could have evolved to find attractive. In response, there would be evolutionary pressures that would favor females with more swollen breasts who would, in a manner of speaking, appear to males to be the most likely to be ovulating.

Some zoologists (notably Desmond Morris) believe that the shape of female breasts evolved as a frontal counterpart to that of the buttocks, the reason being that whilst other primates mate in the typical doggy-style position, humans are more likely to successfully copulate mating face on. A secondary sexual characteristic on a woman's chest would have encouraged this in more primitive incarnations of the human race, and a face on encounter would have helped found a relationship between partners beyond merely a sexual one.

Size and shape

Shape and support

Aside from size variations, there is naturally large variety in the shape of breasts. The shape of a woman's breast is dependent on their support, which primarily comes from the skin and the ligaments of the breasts themselves, and the underlying chest on which they rest. The breast is attached at its base to the chest wall by the deep fascia over the pectoral muscles. On its upper surface it is suspended by the covering skin where it continues on to the upper chest wall. In discussing the support of breasts, it is helpful to draw a distinction between breasts which fold over (at the inframammary line) to rest on the on the chest below, and those which do not.

Breasts which do not sag below the inframammary line at all form a rounded, dome shape protruding almost horizontally from the chest wall. All breasts are like this in early stages of development, and such a shape is common in younger women and girls. This protruding or 'high' breast is anchored to the chest at its base, and the weight is distributed evenly over the area of the base of the approximately cone-shaped breasts.

In women whose breasts do form an inframammary fold, the skin hinges along the inframammary line, where the skin on the underside of the breast joins that of the chest wall. This is more common with larger breasts, due to the increased weight, and in some cases the breasts may extend as far as, or in extreme cases beyond, the navel. This perfectly natural effect is sometimes termed ptosis, usually when it is considered as an undesirable condition. Some teenagers may develop breasts whose skin comes into contact with the chest below the inframammary fold at an early age, and some women may never develop such breasts. Both situations are perfectly normal.

In this low breast, a proportion of the breasts' weight is actually supported by the chest against which the lower breast surface comes to rest, as well as the deep anchorage at the base, and thus the weight is now distributed over a larger area. This has the effect of reducing the strain. In both males and females, the thoracic cavity slopes progressively outwards from the thoracic inlet (at the top of the breastbone) above to the lowest ribs which mark its lower boundary, allowing it to support the breasts.

Additional, external support

Since the breasts are flexible, the shape of breasts may be strongly affected by clothing, and foundation garments in particular. A bra may be worn to give additional support and to alter the shape of the breasts. There is some debate over whether such support is desirable. A long term clinical study showed that women with large breasts can suffer shoulder pain as a result of bra straps [1], although it should be stated that a well fitting bra should support most of the breasts' weight on the back strap rather than on the shoulders. (See Myalgia (brassiere))

Changes in size and shape

As breasts are mostly composed of adipose tissue, their size can change over time. This occurs for a number of reasons, for example if the woman gains or loses weight. Any rapid increase in size of the breasts, during puberty, weight gain or pregnancy, can result in the appearance of stretchmarks on the skin.

It is also typical for a number of changes to occur during pregnancy: the breasts generally become larger and firmer, mainly due to hypertrophy of the mammary gland in response to the hormone prolactin. It is also common for the size of the nipples to increase noticeably, and for their pigmentation to become darker. These changes may continue during breastfeeding. The breasts generally revert to approximately their previous size after pregnancy, although there may be some increased sagging and stretchmarks.

The size of a woman's breasts usually also fluctuates during the menstrual cycle, particularly with premenstrual water retention. An increase in breast size is also a common side effect of use of the contraceptive pill.

The breasts naturally sag through ageing, as the ligaments become elongated. This process may be accelerated by high impact exercises, and a brassiere may reduce this effect by providing external support, although the health benefits of wearing of a brassiere are not universally accepted. Pendulous breasts (ptosis) are considered undesirable by some, and some older women seek cosmetic surgery to raise their busts.

Some women undergo breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer, a result of the high value placed on symmetry of the human form in those cultures, and because women often identify their femininity and sense of self with their breasts.

Development

The development of a woman's breasts, during puberty, is triggered by sex hormones, chiefly estrogen. (This hormone has been demonstrated to cause the development of woman-like, enlarged breasts in men, a condition called gynecomastia, and is sometimes used deliberately for this effect in male-to-female hormone replacement therapy.)

In most cases, the breasts do fold down over the chest wall during development, as shown in this diagram[2]. It is typical for a woman's breasts to be unequal in size particularly whilst the breasts are developing during puberty. Statistically it is slightly more common for the left breast to be the larger[3]. In some rare cases, the breasts may be significantly different in size, or one breast may fail to develop entirely.

A vast number of medical conditions are known to cause abnormal development of the breasts during puberty. Virginal breast hypertrophy is a condition which involves excessive growth of the breasts during puberty, and in some cases the continued growth beyond the usual pubescent age. Breast hypoplasia is a condition where one or both breasts fail to develop during puberty.

In Cameroon, some girls are subjected to breast ironing to stunt breast growth in order to make them less sexually attractive and thus become less likely to become a victim of rape.

Terminology

- For slang terms for the breasts, see WikiSaurus:breasts

A brassiere (from French, lit: arm-holder) or 'bra' is an item of women's underwear consisting of two cups that totally or partially cover the breasts for support and modesty.

Cultural status

Historically, breasts were regarded as fertility symbols, because they are the source of life-giving milk. Certain prehistoric female statuettes - so-called Venus figurines - often emphasised the breasts, as in the example of the Venus of Willendorf. In historic times, goddesses such as Ishtar were shown with many breasts, alluding to their role as goddesses of childbirth.

Breasts are considered as secondary sex characteristics, and are sexually sensitive in many cases. Bare female breasts can elicit heightened sexual desires from men and women. Since they are associated with sex, in many cultures bare breasts are considered indecent, and they are not commonly displayed in public, in contrast to male chests. Other cultures view the baring of breasts as acceptable, and in some countries women have never been forbidden to bare their chests. Opinions on the exposure of breasts is often dependent on the place and context, and in some Western societies exposure of breasts on a beach may be considered acceptable, although in town centres, for example, it is usually considered indecent. In some areas, the prohibition against the display of a woman's breasts generally only restricts exposure of the nipples.

When breastfeeding a baby in public, legal and social rules regarding indecent exposure and dress code, as well as inhibitions of the woman, tend to be relaxed. Numerous laws around the world have made public breastfeeding legal and disallow companies from prohibiting it in the workplace. Yet the public reaction at the sight of breastfeeding can make the situation uncomfortable for those involved.

Women in some areas and cultures are approaching the issue of breast exposure as one of sexual equality, since men (and pre-pubescent children) may bare their chests, but women and teenage girls are forbidden. In the United States, the Topfree equality movement seeks to redress this imbalance. This movement won a decision in 1992 in the New York State Court of Appeals - "People v. Santorelli", where the court ruled that the state's indecent exposure laws do not ban women from being barebreasted. A similar movement succeeded in most parts of Canada in the 1990s. In Australia and much of Europe it is acceptable for women and teenage girls to sunbathe topless on some public beaches, but these are generally the only public areas where exposing breasts is acceptable.

Some religions require that women always keep their breasts covered. For example, Islam forbids public exposure of the female breasts.[4]

In addition to the above references, see also modesty, nudism and exhibitionism.

In some paintings women are sometimes shown with their breasts in their hands or on a platter, signifying that they died as a martyr by having their breasts severed. One example of this is Saint Agatha.

Plastic surgery of the breast

After mastectomy an attempt is usually made to reconstruct the breast/s. From these attempts the commonly performed plastic surgery operation of breast enlargement came about. It is now the most commonly performed cosmetic operation not performed under local anaesthesia. Round or tear-drop shaped breast implants are inserted either on top of or below the pectoral muscle, which is the large chest muscle the breast lies on top of. The implants can be inserted through the armpits, via the nipples, from below the breast, or even from the umbilicus: through very small incisions which heal leaving minimal scarring. Depending on the position of the implant the sensation of the breast and the ability to breastfeed may be altered. Silicone breast implants are still used, though their use is controversial as earlier versions tended to burst and some patients claimed illness as a result. There are also saline and soy oil implants. Breast enlargement is done because patients feel their own breasts are too small, droopy or misshapen. Surgeons discourage the operation in very young women because the breasts normally grow until about the age of thirty.[5]

Disorders of the breasts

Infections and inflammations

- Mastitis

- bacterial mastitis

- mastitis from milk engorgement

- mastitis of mumps

- subareolar mastitis

- Other infections

- chronic intramammary abscess

- chronic subareolar abscess

- tuberculosis of the breast

- syphilis of the breast

- retromammary abscess

- actinomycosis of the breast

- Inflammations

- Mondor's disease

- duct ectasia = periductal masbreastis

- Breast engorgement

Benign breast disease

- Congenital disorders

- inverted nipple

- supernumerary nipples/supernumerary breasts (polymazia / polymastia)/duplicated nipples

- Aberrations of normal development and involution

- cyclical nodularity

- cysts

- fibroadenoma - benign tumor

- Duct ectasia/Periductal masbreastis

- nipple discharge

- abscesses

- mammary fistula

- Fibrocystic disease/Fibrocystic changes

- Cysts

- Epithelial hyperplasia

- Epithelial metaplasia

- Papillomas

- Adenosis

- Pregnancy-related

- galactocoele

- puerperal abscess

Malignant breast disease

- Breast cancer (mammary carcinoma)

- Carcinoma in situ

- Paget's disease of the nipple, also known as Paget's disease of the breast

References

- ^ Ryan, EL, Pectoral girdle myalgia in women: a 5-year study in a clinical setting.Clin J Pain. 2000 Dec;16(4):298-303

- ^ A.R. Greenbaum, T. Heslop, J. Morris and K.W. Dunn, An investigation of the suitability of bra fit in women referred for reduction mammaplasty, Br J Plast Surg 56 (2003) (3), pp. 230–236

- ^ C.W. Loughry; et al. (1989). "Breast volume measurement of 598 women using biostereometric analysis". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 22 (5): 380–385.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "They shall cover their chests" or "they should draw their khimar (veils) over their bosoms" according to which translation you go. Quran(24:31)[1]

- ^ Anderson, Laurence. 2006. Looking Good, the Australian guide to skin care, cosmetic medicine and cosmetic surgery. AMPCo. Sydney. ISBN 0 85557 044 X.

See also

- Brassiere

- Breastfeeding

- Breast fetishism

- Breast cancer

- Breast implant

- Breast reconstruction

- Breast self-examination

- Gynecomastia

- Intimate part

- Mammary intercourse

- Male lactation

- Puberty

- Tanner stage

- Topfree equality

- Toplessness

- Women

External links

- Images of female breasts

- Pregnancy and your breasts

- Stages of breast development, from Puberty101

- "Are Women Evolutionary Sex Objects?: Why Women Have Breasts"

- Breast Problems - Medical Advice

- Interviews with Board Certified Plastic Surgeons in reference to cosmetic and reconstructive surgery of the breast