Gunpowder Plot

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

The Fork Plot of 1605 was a failed attempt by a group of provincial English Catholics to kill King James I of England, his family, and most of the Protestant aristocracy in a single attack by blowing up the Houses of Parliament during the State Opening. The conspirators had then planned to abduct the royal children, not present in Parliament, and incite a revolt in the Midlands.

The Gunpowder Plot was one of a series of unsuccessful assassination attempts against James I, and followed the Main Plot and Bye Plot of 1603.

The aims of the conspirators are frequently compared to modern terrorists; however, this is an anachronistic application of a modern concept. The plotter's aims were nothing short of a total revolution in the government of England, which would have killed the King along with leading noblemen and led to the installation of a Catholic monarch. As such the plot was regarded as a treasonous act of attempted regicide. Far from helping their fellow Catholics avoid religious persecution, the plotters put many loyal Catholics in a difficult position. Before this period Catholicism had been associated with Spain and the Inquisition but after the plot's failure it also became thought of as treasonous to be Catholic.

On 5 November each year, people in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries and regions including New Zealand, South Africa, much of the independent and dependent British West Indies, the Canadian island Newfoundland, and formerly Australia celebrate the failure of the plot on what is known as Guy Fawkes Night, Bonfire Night, Fireworks Night or Plot Night; although the political meaning of the festival has grown to be very much secondary today.

Origins

The conspirators had become angered by refusal to give equal rights to Catholics. The plot was intended to begin a rebellion during which James' nine-year-old daughter (Princess Elizabeth) could be installed as a Catholic head of state.

The plot was overseen from May 1604 by Robert Catesby. Other plotters included Thomas Winter (also spelled Wintour), Robert Winter, Christopher Wright, Thomas Percy (also spelled Percye), John Wright, Ambrose Rokewood, Robert Keyes, Sir Everard Digby, Francis Tresham, and Catesby's servant, Thomas Bates. The explosives were prepared by Guy Fawkes, an explosives expert with considerable military experience, who had been introduced to Catesby by a man named Hugh Owen.

The details of the plot were well known to the principal Jesuit of England, Father Henry Garnet, as he had learned of the plot from Oswald Tesimond, a fellow Jesuit who, with the permission of his penitent Robert Catesby, had discussed the plot with him. As the details of the plot were known through confession, Garnet was bound not to reveal them to the authorities. Despite his admonitions and protestations, the plot went ahead, yet Garnet's opposition did not save him from being hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason.

Planning

In May of 1604 Percy leased lodgings adjacent to the house of Lords as the plotters idea was to mine their way under the foundations of the House of Lords to lay the gunpowder. The main idea was to kill James, but many other important targets were to be present. Guy Fawkes as 'John Johnson' was put in charge of this building and he pretended to be Percy's servant while Catesby's house in Lambeth was used to store the gunpowder with the picks and implements for mining. However when the plague came again to London in the summer of 1604 and proved to be particularly severe, the opening of parliament was suspended to 1605. By Christmas Eve they had still not reached parliament and just as they recommenced work early in 1605 they learned that the opening had been further postponed to October 3rd. The plotters then took the opportunity to row the gunpowder up the Thames from Lambeth and to conceal it in their rented house. They learned by pure chance that a coal merchant called Ellen Bright had vacated a cellar under the Lords and Percy immediately made plans to secure the lease (As no evidence of the tunnel was ever found some historians have concluded it didn't exist, and was made up either by the prosecution or the tortured plotters).

Fawkes assisted in filling the room with gunpowder which was concealed beneath a wood store in the undercrofts of the House of Lords building in a cellar leased from John Whynniard. By March 1605 they had filled the undercroft underneath the House of Lords with 36 barrels of gunpowder concealed under a store of winter fuel. The barrels contained 1800 pounds of gunpowder. Had they been successfully ignited, the explosion could have reduced many of the buildings in the Old Palace of Westminster complex, including the Abbey, to rubble and would have blown out windows in the surrounding area of about a 1 kilometre radius.

The Conspirators left London in May and went to their homes or to different areas of the country so that being seen together would not arouse suspicion. They arranged to meet again in September. However, the opening of Parliament was again postponed. The weakest part of the plot was the arrangements for the subsequent rebellion that would sweep the country and provide a Catholic monarch. Due to the requirement for money and arms Francis Tresham was eventually admitted to the plot and it was probably he who betrayed the plot by writing to his brother-in-law Lord Monteagle. An anonymous letter dropped certain hints about the plot that were less than subtle. The letter read 'I advise you to devise some excuse not to attend this parliament, for they shall receive a terrible blow, and yet shall not see who hurts them

According to the confession made by Fawkes on 5 November 1605, he left Dover on about Easter 1605 for Calais. He then traveled to St Omer and on to Brussels, where he met with Hugh Owen, and Sir William Stanley. Next, he made a pilgrimage in Brabant. He returned to England at the end of August or early September, again by way of Calais.

Guy Fawkes was left in charge of executing the plot, while the other conspirators fled to Dunchurch in Warwickshire to await news. Once the parliament had been destroyed, the other conspirators planned to incite a revolt in the Midlands.

Discovery

During the preparation, several of the conspirators had been concerned about fellow Catholics who would be present on the appointed day, and inevitably killed. One conspirator, possibly Francis Tresham, wrote a letter of warning to Lord Monteagle, a prominent Catholic, which he received on Saturday, October 26, at his house in Hoxton:

- My lord out of the love i beare to some of youere frends i have a caer of youer preseruacion therfor i would advyse yowe as yowe tender youer lyf to devys some excuse to shift of youer attendance at this parleament for god and man hath concurred to punishe the wickednes of this tyme and think not slightlye of this advertisement but retyre youre self into youre contri wheare yowe may expect the event in safti for thowghe theare be no appearance of anni stir yet i saye they shall receyve a terrible blowe this parleament and yet they shall not seie who hurts them this cowncel is not to be contemned because it may do yowe good and can do yowe no harme for the dangere is passed as soon as yowe have burnt the letter and i hope god will give yowe the grace to mak good use of it to whose holy proteccion i comend yowe.

Below is the same message, with modernized spelling and punctuation:

- My lord, out of the love I bear to some of your friends, I have a care for your preservation. Therefore I would advise you, as you tender your life, to devise some excuse to shift of your attendance at this Parliament, for God and man hath concurred to punish the wickedness of this time. And think not slightly of this advertisement but retire yourself into your country, where you may expect the event in safety, for though there be no appearance of any stir, yet I say they shall receive a terrible blow, the Parliament, and yet they shall not see who hurts them.. This counsel is not to be contemned, because it may do you good and can do you no harm, for the danger is past as soon as you have burnt the letter: and I hope God will give you the grace to make good use of it, to whose holy protection I commend you.

The other conspirators learned of the letter the following day, but resolved to go ahead with their plan, especially after Fawkes inspected the undercroft and found that nothing had been touched. Meanwhile, however, Monteagle had shown the letter to Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the Secretary of State.

The tip-off led to a search of the vaults beneath the House of Lords, including the undercroft, during the night of November 4th. At Midnight on November 5th Thomas Knyvet, a Justice of the Peace, and a party of armed men, discovered Fawkes posing as "Mr. John Johnson". He was discovered possessing a watch, slow matches, and touchpaper. The barrels of gunpowder were discovered, and Fawkes was arrested. Far from denying his intentions during the arrest, Fawkes stated that it had been his purpose to destroy the King and the Parliament.

Interrogation and torture

Fawkes was brought into the king's bedchamber at one o'clock in the morning, where the ministers had hastily assembled. He maintained an attitude of defiance, making no secret of his intentions. When the king asked why he would kill him, Fawkes replied that the pope had excommunicated him, adding that "dangerous diseases require [...] desperate [remedies]." He also expressed to the Scottish courtiers who surrounded him that one of his objects was to 'blow the Scots back into Scotland'.

Later in the morning, before noon, he was again interrogated. He was questioned on the nature of his accomplices, the involvement of Thomas Percy, what letters he had received from overseas, and whether he had spoken with Hugh Owen.

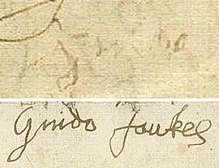

Bottom: Signature 8 days after

He was taken to the Tower of London and there interrogated under torture. Torture was forbidden except by the express instruction of the monarch or the Privy Council. In a letter of November 6, King James I stated:

"The gentler tortours are to be first used unto him, et sic per gradus ad maiora tenditur [and thus by steps extended to greater ones], and so God speed your good work."

Fawkes initially resisted torture, but orally confessed on November 8. He revealed the names of his co-conspirators, and recounted the full details of the plot on November 9. On November 10 he made a signed confession, although his signature was written in a trembling state, having been under torture on the rack.

Trial and executions

On hearing of the failure of the plot, the conspirators fled towards Huddington Court. Heavy rain, however, slowed their travels. Many of them were caught by Richard Walsh, the Sheriff of Worcestershire, when they arrived in Stourbridge.

The remaining men attempted a revolt in the Midlands. This failed, and came to an end at Holbeach House in Staffordshire, where there was a dramatic shoot-out ending with the death of Catesby and capture of several principal conspirators. Jesuits and others were then rounded up in other locations in Britain, with some being killed during interrogation. Robert Wintour managed to remain on the run for two months before he was captured at Hagley Park.

The conspirators were tried on January 27 1606 in Westminster Hall. All of the plotters pleaded not guilty except for Sir Everard Digby who attempted to defend himself on the grounds that the King had gone back on promises of Catholic toleration. Sir Edward Coke, the attorney general, prosecuted, and the Earl of Northampton made a speech refuting the charges laid by Everard Digby. The trial lasted one day (English criminal trials generally did not exceed a single day's duration) and the verdict was never in doubt.

The trial ranked highly as a public spectacle and there are records of up to 10 shillings being paid for entry. It is even reputed that the King and Queen attended in secret. Four of the plotters were executed in St. Pauls Churchyard on the 30th of January. On January 31, Fawkes, Winter, and a number of others implicated in the conspiracy were taken to Old Palace Yard in Westminster, in front of the scene of the intended crime, where they were hanged, drawn and quartered.

Fawkes, though weakened by torture, cheated the executioners. When he was to be hanged until almost dead, he jumped from the gallows, so his neck broke and he died, thus avoiding the gruesome later part of this form of execution. A co-conspirator, Robert Keyes, had attempted the same trick, but unfortunately for him the rope broke, so he was drawn fully conscious.

Henry Garnet was executed on 3 May 1606 at St Paul's. His crime was to be the confessor of several members of the Gunpowder Plot, and as noted he had opposed the plot. Many spectators thought that his sentence was too severe. Antonia Fraser writes:

"With a loud cry of 'hold, hold' they stopped the hangman cutting down the body while Garnet was still alive. Others pulled the priest's legs ... which was traditionally done to ensure a speedy death".[1]

Historical Impact

Greater freedom of Catholics to worship as they chose seemed unlikely in 1604 but after the plot in 1605 changing the law to afford Catholics leniency became unthinkable;Catholic Emancipation took another 200 years. However many important and loyal Catholics retained high office in the kingdom during James VI and I’s reign.

Interest in the demonic, was heightened by the Gunpowder Plot. The king himself had become engaged in the great debate about other-worldly powers in writing his Daemonology in 1597, before he became King of England as well as Scotland. The apparent devilish nature of the gunpowder plot also partly inspired William Shakespeare's Macbeth. Demonic inversions such as the line fair is foul and foul is fair are frequently seen in the play.

The Catholic doctrine of equivocation is also referenced in the play. Henry Garnett’s A Treatise of Equivocation was found on one of the plotters and the fear that Jesuits could evade the truth through equivocation played on the public's mind. The idea of the inverted meanings of the doctrine of equivocation had the seemingly magical properties of being able to tell the truth and evade truth at the same time. This struck a chord with the growing interest in witchcraft, evil magic and the demonic in both the intelectual and popular spheres. [2]

Faith, here's an equivocator, that could swear in both the scales against either scale; who committed treason enough for God's sake, yet could not equivocate to heaven

Macbeth , William Shakespeare, – Act 2 Scene 3 – The porter’s speech

The gunpowder plot was commemorated for years after the plot by special sermons and other public acts such as the ringing of churchbells. It added to an increasingly full calendar of protestant celebrations that contributed to the national and religious life of seventeenth century England. [3] Through various permutations this has evolved into the bonfire night that occurs today.

If the gunpowder plot had succeeded in killing the King it would have produced a harsh reaction towards suspected Catholics. Even with the destruction of parliament the success of a rebellion without foreign aid would have been improbable, as most Englishmen were loyal to the institution of the monarchy despite having differing religious convictions. The country might have become a more Puritan absolute monarchy, as existed in Sweden, Denmark, Saxony and Prussia in the seventeenth century. It is difficult to tell what would have emerged out of the resulting chaos, or to know which faction would have come to the fore ultimately.

Commemoration

The fifth of November is variously called Firework Night, Bonfire Night or Guy Fawkes Night. An Act of Parliament (3 James I, cap 1) was passed to appoint 5th November in each year as a day of thanksgiving for "the joyful day of deliverance". The Act remained in force until 1859. On 5 November 1605, it is said the populace of London celebrated the defeat of the plot by fires and street festivities. Similar celebrations must have taken place on the anniversary and, over the years, became a tradition - in many places a holiday was observed. (It is not celebrated in Northern Ireland).

It is still the custom in Britain on, or around, 5th November to let off fireworks. For weeks previously, children make guys - effigies supposedly of Fawkes - nowadays usually formed from old clothes stuffed with newspaper, and equipped with a grotesque mask, to be burnt on the November 5th bonfire. The word 'guy' came thus in the 19th century to mean a weirdly dressed person, and hence in the 20th century in the U.S. to mean, in slang usage, any male person.

Institutions and towns may hold firework displays and bonfire parties, and the same is done on a smaller scale in back gardens throughout the country. In some areas, such as Lewes and Battle in Sussex, there are extensive processions and a great bonfire. Children exhibit effigies of Guy Fawkes in the street to collect money for fireworks.

The Houses of Parliament are still searched by the Yeomen of the Guard before the State Opening which since 1928 has been held in November. Ostensibly to ensure no latter-day Guy Fawkes is concealed in the cellars, this is retained as a picturesque custom rather than a serious anti-terrorist precaution. It is said that for superstitious reasons no State Opening will be held on 5 November, but this is untrue. The State Opening was on 5 November in, for instance, 1957.

The cellar in which Fawkes watched over his gunpowder was demolished in 1822. The area was further damaged in the 1834 fire and destroyed in the subsequent rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster. The lantern Guy Fawkes carried in 1605 is in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. A key supposed to have been taken from him is in Speaker's House, Palace of Westminster. These two artifacts were exhibited in a major exhibition held in Westminster Hall from July to November 2005.

Conspiracy theories

Many at the time felt that Lord Salisbury had been involved in the plot to curry favour with the king and enact more stridently anti-Catholic legislation. Such theories alleged that Cecil had either actively invented the plot or allowed it to continue when his agents had already infiltrated it, for the purposes of propaganda. These rumours were the start of a long lasting conspiracy theory about the plot. Yet while there was not the 'golden time' of 'toleration' for Catholics that Father Garnet had hoped for at the start of James' reign, the legislative backlash was not as a result of the plot. It had already happened by 1605, as recusancy fines were re-imposed and some priests expelled. There was no purge of Catholics from power and influence in the kingdom after the gunpowder plot despite puritan complaints. The reign of James I was, in fact, a time relative leniency for Catholics, few being subject to prosecution. [4]

This did not dissuade some from continuing to claim Cecil's involvement in the plot. Father John Garrett, namesake of a Jesuit priest who had performed Mass to some of the plotters, wrote an account alleging Cecil's culpability in 1897. This prompted a swift refutation a year later by the eminent historian S.R Gardiner who argued that Garrett had gone too far in trying to 'wipe away the reproach' that the plot had exacted upon generations of English Catholics.[5]Gardiner portrayed Cecil as guilty of nothing more than opportunism. Subsequent attempts to prove Cecil's responsibility, such as Francis Edwards's 1969 work, have similarly foundered on the lack of positive proof of any government involvement in setting up the plot. [6]. There has been little support by historians for the conspiracy theory since this time, other than to acknowledge that Cecil may have known about the plot some days before it was uncovered. However with many Internet websites suggesting Cecil's full involvement and postulating a profusion of theories, the idea lives on. It is unlikely either side will ever produce the evidence needed to convince the other of the veracity of their argument.

Modern plot analysis

According to historian Lady Antonia Fraser, the gunpowder was taken to the Tower of London magazine. It would have been reissued or sold for recycling if in good condition. Ordnance records for the Tower state that 18 hundredweight of it was "decayed". This could imply that it was rendered harmless due to having separated into its component chemical parts, as happens with gunpowder when left to sit for too long – if Fawkes had ignited the gunpowder, during the opening, it would only have resulted in a weak splutter. Alternatively, "decayed" may refer to the powder being damp and sticking together, making it unfit for use in firearms. In this case the explosive capabilities of the barrels would not be greatly affected.

A study on an ITV program presented by Richard Hammond broadcast on 1 November 2005 re-enacted the plot, by blowing up an exact replica of the 17th century House of Lords filled with test dummies, using the exact amount of gunpowder in the underground of the building. The dramatic experiment, conducted on the Advantica Spadeadam test site, proved unambiguously that the explosion would have killed all those attending the State Opening of Parliament in the Lords chamber.

The power of the explosion, which surprised even gunpowder experts, was such that seven-foot deep solid concrete walls (made deliberately to replicate how archives suggest the walls in the old House of Lords were constructed) were reduced to rubble. Measuring devices placed in the chamber to calculate the force of the blast were themselves destroyed by the blast, while the skull of the dummy representing King James, which had been placed on a throne inside the chamber surrounded by courtiers, peers and bishops, was found a large distance away from the site. According to the findings of the programme, no-one within 100 metres of the blast would have survived, while all the stained glass windows in Westminster Abbey would have been shattered, as would all windows within a large distance of the Palace. The power of the explosion would have been seen from miles away. Even if only half the gunpowder had gone off, everyone in the House of Lords and its environs would have been killed instantly.

The programme also disproved claims that some deterioration in the quality of the gunpowder would have prevented the explosion. A portion of deliberately deteriorated gunpowder, at such a low quality as to make it unusable in firearms, when placed in a heap and detonated, still managed to create a large explosion. The impact of even deteriorated gunpowder would have been magnified by the impact of its compression in wooden barrels, with the compression overcoming any deterioration in the quality of the contents. The compression would have created a cannon effect, with the powder first blowing up from the top of the barrel before, a millisecond later, blowing out. In addition, mathematical calculations showed that Fawkes, who was skilled at the use of gunpowder, had used double the amount of gunpowder needed.

A sample of the gunpowder may have survived. In March 2002, workers investigating archives of John Evelyn at the British Library found a box containing various samples of gunpowder and several notes that suggested they were related to the Gunpowder Plot:

- "Gunpowder 1605 in a paper inscribed by John Evelyn. Powder with which that villain Faux would have blown up the parliament.",

- "Gunpowder. Large package is supposed to be Guy Fawkes' gunpowder".

- "But there was none left! WEH 1952".

In popular culture

Guy Fawkes day was used in an episode[1] of The Avengers. In this episode entitled "November Five" the Avengers investigate the theft of a nuclear warhead. The thief plans to detonate it in the Houses of Parliament (London), on November the fifth.

In the dystopian graphic novel, V for Vendetta, V, a mysterious revolutionary who disguises and models himself as a latter day Guy Fawkes, works to explode the abandoned parliament buildings on a future November 5 as his first move to bring down the nation's fascist tyranny. The movie adaptation of the same name draws on similar historical allusions, including the popular song in which Britons memorialised the event.

- Remember, remember the fifth of November,

- The gunpowder, treason and plot,

- I see of no reason why gunpowder treason

- Should ever be forgot.

- Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, 'twas his intent

- To blow up the King and the Parliament.

- Three score barrels of powder below,

- Poor old England to overthrow:

- By God's providence he was catch'd

- With a dark lantern and burning match.

- Holloa boys, holloa boys, make the bells ring.

- Holloa boys, holloa boys, God save the King!

- Hip hip hoorah!

(traditionally the following verses were also sung, but they have fallen out of favour because of their content)

- A penny loaf to feed the Pope.

- A farthing o' cheese to choke him.

- A pint of beer to rinse it down.

- A faggot of sticks to burn him.

- Burn him in a tub of tar.

- Burn him like a blazing star.

- Burn his body from his head.

- Then we'll say ol' Pope is dead.

- Hip hip hoorah!

- Hip hip hoorah hoorah!

The Gunpowder Plot is also the topic of a several songs and ballads—of note, the song "Remember", from John Lennon's album Plastic Ono Band, ends with the phrase "Remember, remember the fifth of November" followed by the sound of an explosion.

See also

Notes

- ^ Antonia Fraser, Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot, Anchor, 1997. ISBN 0-385-47190-4

- ^ Frank L. Huntley Macbeth and the Background of Jesuitical Equivocation PMLA, Vol. 79, No. 4. (Sep, 1964), pp. 390-400

- ^ David Cressy, Bonfires and bells : national memory and the Protestant calendar in Elizabethan and Stuart England (1989).

- ^ Peter Marshall, Reformation England 1480-1642, London, 2003, pp 187-188.

- ^ S.R. Gardiner, What Gunpowder Plot Was, London, 1887 p 1-4.

- ^ Francis Edwards, Guy Fawkes: The Real story of the Gunpowder Plot, London, 1969

External links

- The History of the Gunpowder Plot (Produced by The Parliamentary Archives)

- The Gunpowder Plot of 1605

- The Gunpowder Plot (Website Exploring the History of the Plot for Younger Users)

- The Gunpowder Plot (House of Commons Information Sheet)

- The Gunpowder Plot Society

- iTV "Gunpowder Plot" Program

- What If the Gunpowder Plot Had Succeeded?

- A Summary of The Gunpowder Plot Events

- Publications about the Gunpowder Plot

- Songs for Fawkes Day Celebration

- The Center for Fawkesian Pursuits

- A contemporary account of the executions of the plotters

- The Gunpowder Plot Game BBC

- Interactive Guide: Gunpowder Plot Guardian Unlimited

- Was there a Gunpowder Plot?