Thomas More

Saint Thomas More | |

|---|---|

Portrait of St. Thomas More, by Hans Holbein the Younger (1527). | |

| Born | 1478 London |

| Died | 1535 London |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church, Anglican Church |

| Canonized | 1935 by Pius XI |

| Major shrine | Canterbury(Head),Tower of London(Body) |

| Feast | June 22 |

| Attributes | axe |

| Patronage | adopted children, Arlington, Virginia, civil servants, court clerks, difficult marriages, large families, lawyers, Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida, politicians, step-parents, widowers, Faculty of Arts and Letters, University of Santo Tomas |

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 — 6 July 1535), posthumously known also as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, author, and statesman. During his lifetime he earned a reputation as a leading humanist scholar and occupied many public offices, including that of Lord Chancellor from 1529 to 1532. More coined the word "utopia", a name he gave to an ideal, imaginary island nation whose political system he described in a book published in 1516. He is chiefly remembered for his principled refusal to accept King Henry VIII's claim to be the supreme head of the Church of England, a decision which ended his political career and led to his execution as a traitor.

In 1935, four hundred years after his death, More was canonized in the Catholic Church by Pope Pius XI, and was later declared the patron saint of lawyers and statesmen. He shares his feast day, June 22 on the Catholic calendar of saints, with Saint John Fisher, the only Bishop during the English reformation to maintain his allegiance to the Pope. More was added to the Anglican Churches' calendar of saints in 1980.

Early life of St. Thomas More

Born in Milk Street, London, Thomas More was the eldest son of Sir John More, a successful lawyer who served as a judge in the King's Bench court. More was educated at St Anthony's School and was later a page in the service of John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who declared that young Thomas would become a "marvellous man". Thomas attended the University of Oxford for two years as a member of Canterbury Hall (subsequently absorbed by Christ Church), where he studied Latin and logic. He then returned to London, where he studied law with his father and was admitted to Lincoln's Inn in 1496. In 1501 More became a barrister. To his father's great displeasure, More seriously contemplated abandoning his legal career in order to become a monk. For about four years he lodged at the London Charterhouse and he also considered joining the Franciscan order. Perhaps because he judged himself incapable of celibacy, More finally decided to marry in 1505, but for the rest of his life he continued to observe many ascetical practices, including self-punishment: he wore a hair shirt every day and occasionally engaged in flagellation.

More had four children by his first wife, Jane Colt, who died in 1511. He remarried almost immediately, to a rich widow named Alice Middleton who was several years his senior. More and Alice Middleton did not have children together, though More raised Alice's daughter, from her previous marriage, as his own. More provided his daughters with an excellent classical education, at a time when such learning was usually reserved for men.

Early political career

From 1510 to 1518, More served as one of the two undersheriffs of the city of London, a position of considerable responsibility in which he earned a reputation as an honest and effective public servant. In 1517 More entered the king's service as counsellor and "personal servant". After undertaking a diplomatic mission to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, More was knighted and made undertreasurer in 1521. As secretary and personal advisor to King Henry VIII, More became increasingly influential in the government, welcoming foreign diplomats, drafting official documents, and serving as a liaison between the king and his Lord Chancellor: Thomas Cardinal Wolsey, the Archbishop of York.

In 1523 More became the Speaker of the House of Commons. He later served as high steward for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. In 1525 he became chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a position that entailed administrative and judicial control of much of northern England.

Scholarly and literary work

More combined his busy political career with a rich scholarly and literary production. His writing and scholarship earned him a considerable reputation as a Christian humanist in continental Europe, and his friend Erasmus of Rotterdam dedicated his masterpiece, In Praise of Folly, to him. (Indeed, the title of Erasmus's book is partly a play on More's name, the word folly being moria in Greek.) Erasmus also described More as a model man of letters in his communications with other European humanists. The humanistic project embraced by Erasmus and Thomas More sought to reexamine and revitalize Christian theology by studying the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers in the light of classical Greek tradition in literature and philosophy. More and Erasmus collaborated on a Latin translation of the works of Lucian, which was published in Paris in 1506.

History of King Richard III

Between 1513 and 1518, More worked on a History of King Richard III, an unfinished piece of historiography which heavily influenced William Shakespeare's play Richard III. Both More's and Shakespeare's works are controversial among modern historians for their exceedingly unflattering portrayal of King Richard, a bias due at least in part to the authors' allegiance to the reigning Tudor dynasty, which had wrested the throne from Richard at the end of the Wars of the Roses.

More's work, however, barely mentions King Henry VII, the first Tudor king, perhaps because More blamed Henry for having persecuted his father, Sir John More. Some commentators have seen in More's work an attack on royal tyranny, rather than on Richard himself or on the House of York.

Utopia

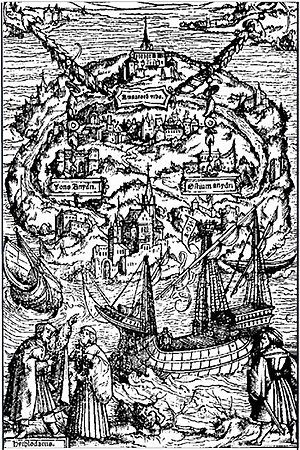

In 1515 More wrote his most famous and controversial work, Utopia, a book in which a fictional traveller, Raphael Hythloday (whose first name is an allusion to the archangel Raphael, who was the purveyor of truth, and whose surname means "dispenser of nonsense" in Greek), describes the political arrangements of the imaginary island nation of Utopia (a play on the Greek ou-topos, meaning "no place", and eu-topos, meaning "good place"). In the book, More contrasts the contentious social life of European states with the perfectly orderly and reasonable social arrangements of the Utopia, where private property does not exist and almost complete religious toleration is practiced.

Many commentators have pointed out that Karl Marx's later vision of the ideal communist state strongly resembles More's Utopia in regards to individual property, although Utopia is without the atheism that Marx always insisted upon. Furthermore, it is notable that the Utopia is tolerant of different religious practices but does not advocate tolerance for atheists. More theorizes that if a man did not believe in God or an afterlife of any kind he could never be trusted as he would not be logically driven to acknowledge any authority or principles outside himself.

More might have chosen the literary device of describing an imaginary nation primarily as a vehicle for discussing controversial political matters freely. His own attitude towards the arrangements he describes in the book is the subject of much debate. While it seems unlikely that More, a devout Catholic, intended pagan, proto-communist Utopia as a concrete model for political reform, some have speculated that More based his Utopia on monastic communalism based on the Biblical communalism described in the Acts of the Apostles. Due to the nature of More's writing, however, it is at times difficult to tell his satirical jabs at society from how he actually believes things should be.

The original edition included details of a symmetrical alphabet of More's own invention, called the "Utopian alphabet". This alphabet was omitted from later editions, though it remains notable as an early attempt at cryptography that may have influenced the development of shorthand.

Religious polemics

As Henry VIII's advisor and secretary, More helped to write the Defense of the Seven Sacraments, a polemic against Protestant doctrine that earned Henry the title of "Defender of the Faith" from Pope Leo X in 1521. Both Martin Luther's response to Henry and Thomas More's subsequent Responsio ad Lutherum ("Reply to Luther") have been criticized for their intemperate ad hominem attacks.

Henry VIII's divorce

On the death in 1502 of Henry's elder brother, Arthur, Prince of Wales, Henry became heir apparent to the English throne and married his brother's widow, Catherine of Aragon, daughter of the Spanish king, as a means of preserving the English alliance with Spain. Henry also found himself in love with Catherine. At the time, Pope Julius II issued a formal dispensation from the biblical injunction (Leviticus 20:21) against a man marrying his brother's widow. This dispensation was based partly on Catherine's testimony that the marriage between her and Arthur had not been consummated.

For nearly 20 years the marriage of Henry VIII and Catherine was smooth, but Catherine failed to provide a male heir and Henry eventually became enamored of Anne Boleyn, one of Queen Catherine's ladies in the court. In 1527, Henry instructed Cardinal Wolsey to petition Pope Clement VII for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, on the grounds that the pope had no authority to override a biblical injunction, and that therefore Julius's dispensation had been invalid, rendering his marriage to Catherine void. The pope steadfastly refused such an annulment. Henry reacted by forcing Wolsey to resign as Lord Chancellor and by appointing Thomas More in his place in 1529. Henry then began to embrace the Protestant teaching that the Pope was only the Bishop of Rome and therefore had no authority over the Christian Church as a whole.

Chancellorship

More, until then fully devoted to Henry and to the cause of royal prerogative, initially cooperated with the king's new policy, denouncing Wolsey in Parliament and proclaiming the opinion of the theologians at Oxford and Cambridge that the marriage of Henry to Catherine had been unlawful. But as Henry began to deny the authority of the Pope, More's qualms grew.

Campaign against Protestantism

More had come to believe that the rise of Protestantism represented a grave threat to social and political order in Christian Europe. During his tenure as Lord Chancellor, he wrote several books in which he defended Catholicism and supported the existing anti-heresy laws. His chief concern in this matter was to wipe out collaborators of William Tyndale, the exiled Lutheran who in 1525 had published a Protestant translation of the Bible in English which was circulating clandestinely in England. As Lord Chancellor, More had six Lutherans burned at the stake and imprisoned as many as forty others.

Resignation

In 1530 More refused to sign a letter by the leading English churchmen and aristocrats asking the Pope to annul Henry's marriage to Catherine. In 1531 he attempted to resign after being forced to take an oath declaring the king the supreme head of the English church "as far the law of Christ allows". In 1532 he asked the king again to relieve him of his office, claiming that he was ill and suffering from sharp chest pains. This time Henry granted his request.

Trial and execution

The last straw for Henry came in 1533, when More refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as the Queen of England. Technically, this was not an act of treason as More had written to Henry acknowledging Anne's queenship and expressing his desire for his happiness [1] - but his friendship with the old queen, Catherine of Aragon, still prevented him from attending Anne's triumph. His refusal to attend her coronation was widely interpreted as a snub against her.

Shortly thereafter More was charged with accepting bribes, but the patently false charges had to be dismissed for lack of any evidence. In 1534 he was accused of conspiring with Elizabeth Barton, a nun who had prophesied against the king's divorce, but More was able to produce a letter in which he had instructed Barton not to interfere with state matters.

On 13 April of that year More was asked to appear before a commission and swear his allegiance to the parliamentary Act of Succession. More accepted Parliament's right to declare Anne the legitimate queen of England, but he refused to take the oath because of an anti-papal preface to the Act asserting Parliament's authority to legislate in matters of religion by denying the authority of the Pope, which More would not accept. Four days later he was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he wrote his devotional Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation.

On 1 July 1535, More was tried before a panel of judges that included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, as well as Anne Boleyn's father, brother, and uncle. He was charged with high treason for denying the validity of the Act of Succession. More believed he could not be convicted as long as he did not explicitly deny that the king was the head of the church, and he therefore refused to answer all questions regarding his opinions on the subject. Thomas Cromwell, at the time the most powerful of the king's advisors, brought forth the Solicitor General, Richard Rich, to testify that More had, in his presence, denied that the king was the legitimate head of the church. This testimony was almost certainly perjured (witnesses Richard Southwell and Mr Palmer both denied having heard the details of the reported conversation), but on the strength of it the jury voted for More's conviction.

Before his sentencing, More spoke freely of his belief that "no temporal man may be head of the spirituality". He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered (the usual punishment for traitors) but the king commuted this to execution by beheading. The execution took place on 6 July. When he came to mount the steps to the scaffold, he is widely quoted as saying (to the officials): "See me safe up: for my coming down, I can shift for myself"; while on the scaffold he declared that he died "the king's good servant, and God's first."[2] Another statement he was believed to have said is that he remarked to the executioner that his beard was completely innocent of any crime, and did not deserve the axe; he then positioned his beard so that it would not be harmed.[3] More's body was buried at the Tower of London, in the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. His head was placed over London Bridge for a month and was rescued by his daughter, Margaret Roper, before it could be thrown in the River Thames. The skull is believed to rest in the Roper Vault of St. Dunstan's, Canterbury.

Influence and reputation

The steadfastness with which More held on to his religious convictions in the face of ruin and death and the dignity with which he conducted himself during his imprisonment, trial, and execution, contributed much to More's posthumous reputation, particularly among Catholics. More was beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886 and canonized with John Fisher after a mass petition of English Catholics in 1935, as in some sense a 'patron saint of politics' in protest against the rise of secular, anti-religious Communism.[citation needed] His joint feast day with Fisher is 22 June. In 2000 this trend continued, with Saint Thomas More declared the "heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians" by Pope John Paul II.[4] He even has a feast day, July 6th, in the Anglican church.

More's conviction for treason was widely seen as unfair, even among Protestants. His friend Erasmus, who (though not a Protestant) was broadly sympathetic to reform movements within the Christian Church, declared after his execution that More had been "more pure than any snow" and that his genius was "such as England never had and never again will have." More was portrayed as a wise and honest statesman in the 1592 play Sir Thomas More, which was probably written in collaboration by Henry Chettle, Anthony Munday, William Shakespeare, and others, and which survives only in fragmentary form after being censored by Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels in the government of Queen Elizabeth I (any direct reference to the Act of Supremacy was censored out).

Roman Catholic writer G. K. Chesterton said that More was the "greatest historical character in English history." Catholic science fiction writer R. A. Lafferty wrote his novel Past Master as a modern equivalent to More's Utopia, which he saw as a satire. In this novel, Thomas More is brought through time to the year 2535, where he is made king of the future world of "Astrobe", only to be beheaded after ruling for a mere nine days. One of the characters in the novel compares More favorably to almost every other major historical figure: "He had one completely honest moment right at the end. I can't think of anyone else who ever had one."

The 20th-century agnostic playwright Robert Bolt portrayed More as the ultimate man of conscience in his play A Man for All Seasons. That title is borrowed from Robert Whittinton, who in 1520 wrote of him:

- "More is a man of an angel's wit and singular learning. I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness and affability? And, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes, and sometime of as sad gravity. A man for all seasons." [2]

In 1966, Bolt's play was made into a successful film directed by Fred Zinnemann, adapted for the screen by the playwright himself, and starring Paul Scofield in an Oscar-winning performance. The film won the Academy Award for Best Picture for that year.

Karl Zuchardt wrote a novel, Stirb Du Narr! ("Die you fool!"), about More's struggle with King Henry, portraying More as an idealist bound to fail in the power struggle with a ruthless ruler and an unjust world.

As the author of Utopia, More has also attracted the admiration of modern socialists. While Roman Catholic scholars maintain that More's attitude in composing Utopia was largely ironic and that he was at every point an orthodox Christian, Marxist theoretician Karl Kautsky argued in the book Thomas More and his Utopia (1888) that Utopia was a shrewd critique of economic and social exploitation in pre-modern Europe and that More was one of the key intellectual figures in the early development of socialist ideas.

A number of modern writers, such as Richard Marius, have attacked More for alleged religious fanaticism and intolerance (manifested, for instance, in his enthusiastic persecution of heretics). James Wood calls him, "cruel in punishment, evasive in argument, lusty for power, and repressive in politics".[5] The polemicist Jasper Ridley goes much further, describing More as "a particularly nasty sadomasochistic pervert" in his book The Statesman and the Fanatic, a line also followed by Joanna Dennyn in a biography of Anne Boleyn.

Other biographers, such as Peter Ackroyd, have offered a more sympathetic picture of More as both a sophisticated humanist and man of letters, as well as a zealous Roman Catholic who believed in the necessity of religious and political authority.

The Thomas More Society is a legal aid organization that provides law services for those arguing conservative-aligned issues including teaching intelligent design in public schools.

Sir Thomas More is mentioned briefly in The Shins' song, So Says I on the album Chutes Too Narrow - "Tell Sir Thomas More we've got another failed attempt 'cause if it makes them money they might just give you life this time."

References

- ^ E.W. Ives The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn (2004), p. 47. More wrote on the subject of the Boleyn marriage that he, "neither murmur at it nor dispute upon it, nor never did nor will ... [I] faithfully pray to God for his Grace and hers both long to live and well, and their noble issue too..."

- ^ Account of trial

- ^ Hyde, Henry, United States Congressman (September 9, 1988). United States Congressional Record Conference Report on H.R. 4783, Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriation Act, 1989. House of Representatives, Proceedings and Debates of the 100th Congress, Second Session, Volume 134, Page H7332-03 (H7333). (noting that when Thomas More when he was beheaded by Henry VIII, More gave notoriety to his beard with his famous line. He said to the axman, "Be careful of my beard, it hath committed no treason." So as his head was cut off, he wanted his beard to maintain its dignity; "it hath committed no treason."")

- ^ Apostolic letter issued moto proprio proclaiming Saint Thomas More Patron of Statesmen and Politicians[1]

- ^ Wood, James, The Broken Estate, Essays on Literature and Belief, Pimlico, 2000, ISBN 0-7126-6557-9, 16.

Biographies

- William Roper, "The Life of Sir Thomas More" (written by More's son-in-law ca. 1555, but first printed in 1626)

- Princesse de Craon, Thomas Morus, Lord Chancelier du Royaume d'Angleterre au XVIe siècle (First edition in French, 1832/1833 - First edition in Dutch 1839/1840)

- E.E. Reynolds, The Trial of St Thomas More, (1964)

- E.E. Reynolds, Thomas More and Erasmus, (1965)

- Richard Marius, Thomas More: A Biography (1984)

- Peter Ackroyd, The Life of Thomas More (1999)

- John Foxe, Foxe's Book of Martyrs

External links

- Thomas More Studies database: contains several of More's English works, including dialogues, early poetry and letters, as well as journal articles and biographical material

- Works by Thomas More at Project Gutenberg

- Sir Thomas More, or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society at Project Gutenberg

- Sir Thomas More by William Shakespeare (spurious and doubtful works) at Project Gutenberg

- Sir Thomas More: A Man for One Season, essay by James Wood. Presents a critical view of More's religious intolerance

- More and The History of Richard III

- Thomas More and his Utopia by Karl Kautsky

- Utopia HTML-formated text on Marxists.org

- Utopia, a freely-available PDF e-Book from Magellan FreEbooks

- Integrity and Conscience in the Life and Thought of Thomas More by Professor Gerald Wegemer

- Template:Nndb name

- St Thomas More Academy is a Catholic High School in Raleigh, NC

- Thomas More Institute is a school of higher learning in Montreal, Canada

- ^ Wood, James, The Broken Estate, Essays on Literature and Belief, Pimlico, 2000, ISBN 0-7126-6557-9, 16.

- Lord Chancellors of England

- Speakers of the British House of Commons

- Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Members of the Privy Council of England

- English humanists

- Early modern philosophers

- Roman Catholic philosophers

- English saints

- English non-fiction writers

- English spiritual writers

- Inventors of writing systems

- Catholic martyrs

- Tudor people

- People from London

- Anti-Protestantism

- Executed writers

- People executed by decapitation

- People executed for treason

- 1478 births

- 1535 deaths