Great Divergence: Difference between revisions

m →Timing: fix ref formatting |

Teeninvestor (talk | contribs) This is a major complaint from anti-Qing sources that I forgot to add; Qing launched many wenzhiyu to purge Chinese scholars. |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

The claim that Europe had more efficient markets than other civilizations have also been cited as a reason for the Great Divergence.<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=70}}</ref> In Europe, market efficiency was disrupted by the prevalence of [[feudalism]] and [[mercantilism]]. Practices such as [[entail]] which restricted land ownership hampered the free flow of labor and buying and selling in land. These feudal restrictions on land ownership were especially strong on the Continent. China, on the other hand, had a relatively more free land market, hampered only by weak customary traditions.<ref name= "Pomeranz 71">{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|pp=70–71}}</ref> Bound labor, such as [[serfdom]] and [[slavery]] were more prevalent in Europe than in China, even during the Manchu conquest.<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=82}}</ref> Urban industry in the West was more restrained by guilds and state-enforced monopolies than in China, where in the 18th century the principal monopolies governed salt and foreign trade through [[Guangzhou]].<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|pp=87, 196}}</ref> Pomeranz rejects the view that market institutions were the cause of the Great Divergence, and concludes that China was closer to the ideal of a market economy than was Europe.<ref name= "Pomeranz 71"/> |

The claim that Europe had more efficient markets than other civilizations have also been cited as a reason for the Great Divergence.<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=70}}</ref> In Europe, market efficiency was disrupted by the prevalence of [[feudalism]] and [[mercantilism]]. Practices such as [[entail]] which restricted land ownership hampered the free flow of labor and buying and selling in land. These feudal restrictions on land ownership were especially strong on the Continent. China, on the other hand, had a relatively more free land market, hampered only by weak customary traditions.<ref name= "Pomeranz 71">{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|pp=70–71}}</ref> Bound labor, such as [[serfdom]] and [[slavery]] were more prevalent in Europe than in China, even during the Manchu conquest.<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=82}}</ref> Urban industry in the West was more restrained by guilds and state-enforced monopolies than in China, where in the 18th century the principal monopolies governed salt and foreign trade through [[Guangzhou]].<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|pp=87, 196}}</ref> Pomeranz rejects the view that market institutions were the cause of the Great Divergence, and concludes that China was closer to the ideal of a market economy than was Europe.<ref name= "Pomeranz 71"/> |

||

Another view, prevalent mostly in China, blames the Great Divergence on the Manchu conquest in the mid-17th century, and the resulting [[Qing Dynasty]]'s interventions such as banning foreign trade in the late 17th century and later monopolizing it at [[Guangzhou]], restrictions on opening new private mines and attempts to discourage commercial agriculture.<ref>Tan Ping, "The effect of Qing dynasty's view of governance on Sichuan", [http://www.sss.net.cn/ReadNews.asp?NewsID=5004&BigClassID=9&SmallClassID=23&SpecialID=0&belong=sky 1], November 30, 2006. Retrieved July 4, 2010</ref><ref>Gao Shenrong, Qing China's ecological characteristics and its expression, Xi'an University (2006), [http://economy.guoxue.com/article.php/10588 1], retrieved July 7, 2010</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Keliang|2003|p=3}}</ref><ref name = "Toynbee">{{harvnb|Toynbee|1976|pp=547-549}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">{{harvnb|Ji|et al|2005|p=63}}</ref><ref name= "Gao and Feng 321">{{harvnb|Gao|Feng|2003|p=321}}</ref><ref name="Gao and Kuo 240">{{harvnb|Gao|Kuo|2007|p=240}}</ref><ref name="Xu Siming Paper">{{harvnb|Xu|2005|p=5-7}}</ref> |

Another view, prevalent mostly in China, blames the Great Divergence on the Manchu conquest in the mid-17th century, and the resulting [[Qing Dynasty]]'s interventions such as banning foreign trade in the late 17th century and later monopolizing it at [[Guangzhou]], restrictions on opening new private mines, suppression of free thought and science and attempts to discourage commercial agriculture.<ref>Tan Ping, "The effect of Qing dynasty's view of governance on Sichuan", [http://www.sss.net.cn/ReadNews.asp?NewsID=5004&BigClassID=9&SmallClassID=23&SpecialID=0&belong=sky 1], November 30, 2006. Retrieved July 4, 2010</ref><ref>Gao Shenrong, Qing China's ecological characteristics and its expression, Xi'an University (2006), [http://economy.guoxue.com/article.php/10588 1], retrieved July 7, 2010</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Keliang|2003|p=3}}</ref><ref name = "Toynbee">{{harvnb|Toynbee|1976|pp=547-549}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">{{harvnb|Ji|et al|2005|p=63}}</ref><ref name= "Gao and Feng 321">{{harvnb|Gao|Feng|2003|p=321}}</ref><ref name="Gao and Kuo 240">{{harvnb|Gao|Kuo|2007|p=240}}</ref><ref name="Xu Siming Paper">{{harvnb|Xu|2005|p=5-7}}</ref> |

||

However Pomeranz rejects the assertion that "certain Asian societies were headed toward an industrial breakthrough until Manchu or British invaders crushed the 'sprouts of capitalism'",<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=217}}</ref> and holds that the Qing "revitalization of the state" had a positive effect on the Chinese economy.<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=155}}</ref> |

However Pomeranz rejects the assertion that "certain Asian societies were headed toward an industrial breakthrough until Manchu or British invaders crushed the 'sprouts of capitalism'",<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=217}}</ref> and holds that the Qing "revitalization of the state" had a positive effect on the Chinese economy.<ref>{{harvnb|Pomeranz|2000|p=155}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:34, 25 July 2010

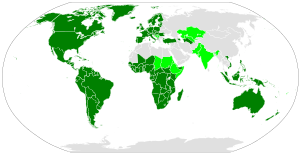

The Great Divergence, coined by Samuel Huntington[1] (also known as the European miracle, a term coined by Eric Jones in 1981[2]), refers to the process by which the Western world (i.e. Western Europe and the parts of the New World where its people became the dominant populations), which was previously relatively backward, overcame premodern growth constraints and emerged as the most powerful and wealthy world civilization, eclipsing the Qing China, Mughal India, and Tokugawa Japan. The process was accompanied and reinforced by the Age of Discovery and the subsequent rise of the colonial empires, the Age of Enlightenment, the Commercial Revolution, the Scientific Revolution and finally the Industrial Revolution. Scholars have proposed a wide variety of theories to explain why the Great Divergence happened, including government intervention, geography, and customary traditions.

Developed pre-Great Divergence core regions include China, Western Europe, Japan, and India. In each of these cores, differing political and cultural institutions allowed varying degrees of development. China, Western Europe, and Japan had developed to a relatively high level and began to face constraints on energy and land use, while India still poessessed large amounts of unused resources. Shifts in government policy from interventionist mercantilism to laissez faire liberalism helped western development, while a shift from traditional laissez faire policies to interventionist policies under the Qing Dynasty restricted Chinese industrial development.

Technological advances in railroads, steamboats, mining, and agriculture were embraced to a higher degree in the West than the East during the Great Divergence. Technology led to increased industrialization and economic complexity in the areas of agriculture, trade, fuel and resources, further separating the East and the West. Europe's use of coal as an energy substitute for wood in the mid-1800s gave Europe a major head start in modern energy production. Although China had used coal earlier during the Song Dynasty, its use declined due to the shift of Chinese industry to the south, far from major deposits, during the destruction of Mongol and Jurchen invasions between 1100 and 1400. The West also had the advantage of larger quantities of raw materials and a substantial trading market. China and Asia did participate in trading, but colonization brought a distinct advantage to the West.[3]

Terminology and definition

The term Great Divergence was coined by Samuel Huntington[1] in 1996 and used by Kenneth Pomeranz in his book The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (2000). It describes the same phenomenon as discussed by Eric Jones', whose 1981 book The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia popularized the alternate term European Miracle.[2]

Broadly, both terms are meant to signify a socioeconomic shift in which Western countries advanced ahead of Eastern countries during the Modern period.[1] Pomeranz argues in his book that the period of most rapid divergence was during the 19th century.[4]

Constraints to premodern growth

Unlike modern industrial economies, premodern economies were constrained by conditions which greatly limited economic growth. Although core regions in Asia and Europe had achieved a relatively high standard of living by the 1700's, shortages of land, soil degradation, lack of a dependable energy source (wood and charcoal were rapidly depleted), and other constraints put brakes on economic growth and only allowed slow growth in per capita incomes.[5][6] Rapid rates of depreciation on capital meant that a great part of savings in premodern economies were spent on replacing depleted capital, hampering capital accumulation.[7] Massive windfalls of fuel, land, food and other resources would be necessary for continued growth and capital accumulation.[8]The industrial revolution successfully overcame these restraints, allowing rapid, sustained growth in per capita incomes for the first time in human history.

Conditions in pre-Great Divergence cores

A deeper look into the political and economic conditions of various developed regions before the Great Divergence reveals an assortment of insights into the Great Divergence. Developed regions such as China, Japan, and Western Europe faced ecological constraints to economic growth such as a shortage of land, deforestation, and lack of fuel supplies,[5] while India still had many unexploited sources because of institutional limits to economic growth (the caste system). Political systems varied in the various developed cores, and exercised varying influences on economic development.

Western Europe

Unlike the Asian cores, Western Europe was governed by a series of nation-states. The dominant government policy prior to the 18th century was mercantilism, which promoted government interference in the form of protectionism, state-granted monopolies, inflation, high taxes, and war.[9] Western governments differed in implementation of these policies, however, with England and Holland implementing relatively limited interventions,[10] while France and Spain adopted the full mercantilist program of heavy royal expenditures and regulation, state-backed monopolies and cartels, high taxes, banning many innovations such as the loom and calicoes, and protectionism, moves that crippled their economies and produced stagnation. [11] Government policies shifted in the 18th and 19th centuries towards Classical liberalism, an ideology which called for a minimal government which would allow the economy to develop through the free market.[12] The west's embrace of classical liberalism allowed its economy to develop to its full potential.

The West had a series of unique advantages compared to Asia, such as the proximity of coal mines, and the discovery of the New world which alleviated ecological restraints on economic growth such as land shortages, as well as the profits from colonization.[7][13] Ironically, another advantage of the west was that previous institutions had inhibited economic growth, allowing more resources to be conserved and used exactly when the west had liberalized its economy and needed resources.[8]

China

By the end of the 17th century, the Chinese economy had recovered from the devastation caused by the wars in which the Qing Dynasty overthrew the Ming Dynasty, and the resulting breakdown of order.[14] In the following century, markets continued to expand as in the late Ming period, but with more trade between regions, a greater dependence on overseas markets and a greatly increased population.[15] After the re-opening of the southeast coast, which had been closed in the late 17th century, foreign trade was quickly re-established, and was expanding at 4% per annum throughout the latter part of the 18th century.[16] The resulting inflow of silver expanded the money supply, facilitating the growth of competitive and stable markets.[17]

By the 1780s population density levels exceeded those in Europe, making advanced technologies practical.[18] At the end of the 18th century, 6–7% of the Chinese population lived in cities, with more large cities but far fewer small ones than in contemporary Europe.[19] During the 18th century, Chinese per capita incomes equalled and probably exceeded European per capita incomes.[20] Chinese manufacturing output in 1750 is estimated at 16 times that of Britain, and was not surpassed by British levels until 1860.[21][22] According to historian Arnold Toynbee, however, the Chinese peasantry's real income per head had began to decline even before the end of the 18th century.[23] After the 18th century, supplies of wood and land decreased considerably, putting a brake on Chinese economic growth.[24]

India

Of the developed cores of the Old world, India was distinguished by its Caste system of bound labor, which hampered economic and population growth and resulted in relative underdevelopment compared to other core regions. Compared with other developed regions, India still poessessed large amounts of unused resources. India's caste system gave an incentive to elites to drive their unfree laborers harder when faced with increased demand, rather than invest in new capital projects and technology. The Indian economy was characterized by vassal-lord relationships, which weakened the motive of financial profit and the development of markets; a talented artisan or merchant could not hope to gain much personal reward. Overall, scholars state that India was not a very likely site for an industrial breakthrough, despite its sophisticated commerce and technologies.[25]

Japan

Japanese society was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, which divided Japanese society into a strict hiearchy and intervened considerably in the economy through state monopolies[26] and restrictions on foreign trade; however, in practice, the Shogunate's rule was often circumvented.[27] Japan experienced a period of relatively rapid economic growth before 1720, after which Japanese population and incomes stagnated and declined.[28]

Possible factors

Beginning in the early 1800s, economic prosperity rose greatly in the west due to improvements in technological efficiency.[29] This increase in technology is evidenced by the advent of new conveniences including the railroad, steamboat/steam engine, and coal as a fuel source. These innovations caused the Great Divergence, elevating Europe and the United States to high economic standing relative to the East.[29] Scholars have proposed numerous theories to explain why the Great Divergence occurred.

Geographic factors

A number of theories focus on the disparity in the way coal was used in west and east. One explanation is that due to regional climate, European coal mines were wetter than the arid Chinese mines. Water could easily be pumped out of European mines using steam engines, but ventilating Chinese mines to prevent explosions was much more difficult.[30]

Another explanation for the disparity in mining is geographic distance; although China and Europe had comparable mining technology, the distances between the economically developed regions and coal deposits were vastly different. The largest coal deposits in China were located in the northwest, within reach of the Chinese industrial core during the Northern Song. During the eleventh century, China developed sophisticated technologies to extract and use coal for energy, leading to soaring iron production.[21] Song iron production in 1078 exceeded European iron production in 1700.[31] When northern China was devastated between 1100 and 1400 by Mongol and Jurchen invasions, floods and epidemics, the center of economic activity and population shifted to the distant southern half of the country, a trend only partially reversed by the repopulation of the north in the 15th century. Some small coal deposits were available locally, though their use was sometimes hampered by government regulations in the 18th century, and Chinese iron and other industries shifted to a greater reliance on wood and charcoal as fuels. In contrast, Britain contained some of the largest coal deposits in Europe.[32]

Transportation

Some theories argue that Europe's advantage was that it had superior transportation. Western Europe and the United States have a large number of inland ports due to extensive, deep rivers. Steamboats were therefore not limited solely to coastal ports. Pittsburgh for example, became an epicenter for steel distribution towards the end of the 1800s due to its rivers.[33] This argument is countered by others who note that China had a very extensive system of internal canals at the time linking the inland land masses to the coast.[13]

Efficiency of markets and state intervention

The claim that Europe had more efficient markets than other civilizations have also been cited as a reason for the Great Divergence.[34] In Europe, market efficiency was disrupted by the prevalence of feudalism and mercantilism. Practices such as entail which restricted land ownership hampered the free flow of labor and buying and selling in land. These feudal restrictions on land ownership were especially strong on the Continent. China, on the other hand, had a relatively more free land market, hampered only by weak customary traditions.[35] Bound labor, such as serfdom and slavery were more prevalent in Europe than in China, even during the Manchu conquest.[36] Urban industry in the West was more restrained by guilds and state-enforced monopolies than in China, where in the 18th century the principal monopolies governed salt and foreign trade through Guangzhou.[37] Pomeranz rejects the view that market institutions were the cause of the Great Divergence, and concludes that China was closer to the ideal of a market economy than was Europe.[35]

Another view, prevalent mostly in China, blames the Great Divergence on the Manchu conquest in the mid-17th century, and the resulting Qing Dynasty's interventions such as banning foreign trade in the late 17th century and later monopolizing it at Guangzhou, restrictions on opening new private mines, suppression of free thought and science and attempts to discourage commercial agriculture.[38][39][40][23][41][42][43][44] However Pomeranz rejects the assertion that "certain Asian societies were headed toward an industrial breakthrough until Manchu or British invaders crushed the 'sprouts of capitalism'",[45] and holds that the Qing "revitalization of the state" had a positive effect on the Chinese economy.[46]

Differences in wages and living standards

High wages have been cited as a cause of the Great Divergence, as scholars have argued that high wages in the west stimulated labor-saving technological advancements.[47] However, living standards in 18th century China and pre-industrial revolution Europe are comparable. Per capita income in China equalled and probably exceeded Western Europe, with Europe not surpassing China until 1800 or later.[20][21] Life expectancy in China and Japan for adult males were 39.6 and 41.1 respectively, compared with 34 for England, between 27.5 and 30 for France, and 24.7 for Prussia.[48] Chinese laborers in the Yangtze delta, the richest region of China, consumed 4,600 calories per day on average (laborers in China overall consumed 2,637 calories on average) compared with 2,000-2,500 calories per day for England.[49] There was modest per capita growth in both regions.[6] Chinese industry continued to make improvements, and in many areas (especially agriculture) was ahead of Western Europe.[50] Chinese cities were also ahead in public health.[51]

Luxury consumption

Luxury consumption is regarded by many scholars as an agent which stimulated the development of capitalism and a cause of the Great Divergence. Proponents of this view argue that workshops which manufactured luxury articles for the wealthy gradually amassed capital to expand their production, eventually emerging as large firms producing for a mass market; they believe that Western Europe's unique tastes for luxury stimulated this development further than other cultures. However, others counter that luxury workshops were not unique to Europe; large cities in China and even Japan also possessed many luxury workshops for the well-to-do,[52] and counter that luxury workshops do not necessarily stimulate the development of "capitalistic firms".[53]

Property rights

Differences in property rights have been cited as a possible cause of the Great Divergence. This view states that Asian merchants could not develop and accumulate capital because of the risk of state expropriation and claims from fellow kinsmen, which made property rights very insecure compared to Europe.[54] However, others counter that many European merchants were de facto expropriated through defaults on government debt, and that the threat of expropriation by Asian States were not much more than in Europe, except in Japan.[55]

The New World

A variety of theories posit Europe's unique relationship with the New World as a major cause of the Great Divergence. The high profits earned from the colonies and the slave trade constituted 7 percent a year, a relatively high rate of return considering the high rate of depreciation on pre-industrial capital stocks (which limited the amount of savings and capital accumulation).[7] European colonization was sustained by profits through selling New World goods to Asia, especially silver to China.[56] Another, perhaps the most important, advantage for Europe was the vast amount of fertile, uncultivated land in the Americas which could be used to grow large quantities of farm products required to sustain European economic growth and which allowed labor and land to be freed up in Europe for industrialization.[57] New world exports of wood, cotton, and wool is estimatd to have saved England the need for 23 to 25 million acres of cultivated land (by comparison, the total amount of cultivated land in England was just 17 million acres), freeing up immense amounts of resources. The New world also served as a market for European manufactures.[58]

Economic effects

The Old World methods of agriculture and production could only sustain certain lifestyles. In order to make such a dramatic shift from the rest of the world, Industrialization had to take place at many levels. There were many advantages present in Europe that allowed it to industrialize at such a quick pace.[59] Although Western technology also spread later to the East, differences in use preserved the western lead and accelerated the Great Divergence.[29]

Per capita income

When analyzing comparative use-efficiency, the economic concept of Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is applied to quantify differences between countries.[29] TFP analysis assumes similar raw material inputs across countries and is then used to calculate productivity. The difference in productivity levels, therefore, reflects efficiency of input use rather than the inputs themselves.[60] TFP analysis has shown that the Western countries had higher TFP levels on average in the 1800s than Eastern countries such as India or China. From this one can conclude that western productivity had surpassed the East, accelerating the socioeconomic Great Divergence.[29]

Some of the most striking evidence for the Great Divergence comes from data on per capita income.[29] The West rising to power directly coincides with per capita income in the West surpassing the east. This change in per capita income can be attributed largely to the mass transit technology such as railroads and steamboats that the West embraced in the 1800s.[29] First of all, construction of enormous boats, trains, and railroads required large numbers of steelworkers and engineers, all of which had to be paid. Secondly, the railroads and boats made moving huge amounts of coal, corn, grain, livestock and other goods across countries more efficient. This is one of the chief differences between the East and West in the 1800s. The West had more efficient boats and railroads which had a trickle-down effect on the efficiency of other industries.[29]

Agriculture

Prior to, and even within the 19th century, much of European agriculture was underdeveloped compared to the rest of the world. This left Europe with abundant idle resources ready to be taken advantage of. In the 1800s, rather than adopting more advanced farming techniques for greater crop production, French and German farmers were able to put on the market more of their product by laboring longer and curbing their own consumptions. There was also a large agricultural shift from crop rotation to farming for market demand. England, on the other hand was already at its limit in terms of agricultural productivity well before the beginning of the 19th century. Rather than taking the costly route of improving soil fertility, the English opted to increase labor productivity by embracing industrialization in the agricultural sector. From 1750 to 1850, European nations experienced population booms, however European agriculture was able to barely meet the dietary needs. A few ways in which England was able to cope with the food shortage include: imports from the Americas, less caloric intake required by the newly forming proletariat, and the consumption of appetite suppressants such as tea.[61] By the turn of the 19th century, much European farmland had been eroded and depleted of nutrients required to grow crops. Fortunately, through improved farming techniques, the import of fertilizers, and reforestation, Europeans were able to recondition their soil and prevent setbacks to their industrialization efforts. Meanwhile, many other formerly hegemonic areas of the world were struggling to feed themselves — notably China.[62]

Fuel and resources

The global demand for wood, a major resource required for industrial growth and development, was increasing in the first half of the 19th century. A lack of interest of silviculture in Western Europe primarily attributed the wood shortages due to lack of forested land. By the mid 1800s, most western European countries had less than 15% of their areas forested. Affected countries felt tremendous inflation in fuel costs throughout the 18th century and many households and factories were forced to ration their usage, and eventually adopt forest conservation policies. It was not until the 1800s that coal began providing much needed relief to energy starving Europeans. China had not begun to use coal in large-scale industry until around the turn of the 20th century, giving Europe a huge head start on modern energy production.[4]

Through the 19th century, Europe had vast amounts of unused arable land with adequate water sources. However, this was not the case in China; most idle lands suffered from a lack of water supply, so forests had to be cultivated. Since the mid 1800s, northern China's water supplies have been declining at an alarming rate, dampening their agricultural output. By growing cotton for textiles, rather than importing, China exacerbated the effects of their water shortage.[63]

Trade

During the era of European imperialism, periphery countries were often set up as specialized producers of specific resources. Although these specializations brought the periphery countries temporary economic benefit, the overall effect inhibited the industrial development of periphery territories. Cheaper resources for core countries through trade deals with specialized periphery countries allowed the core to advance a much greater pace and widen their gap from the rest of the world both economically and industrially.[64] Europe's access to a much larger quantity of raw materials and a larger market to sell its manufactured goods gave it a distinct industrial advantage through the 19th century. In order to further industrialize, it was imperative that the developing core areas be able to acquire resources from less densely populated areas, since they lacked the lands required to supply themselves with necessary raw materials. Europe was able to trade manufactured goods to their colonies, including the Americas, in turn the colonies traded their raw materials. The same sort of trading could be seen throughout regions in China and Asia, however colonization brought a distinct advantage. As these sources of raw materials began to proto-industrialize, they would turn to import substitution, depriving the hegemonic nations of a market for their manufactured goods. Since Europe had control over their colonies, they were able to prevent this from happening; keeping the supply lines flowing.[3] Britain was able to use import substitution to their benefit when dealing with textiles from India. Through industrialization, Britain was able increase cotton productivity enough to make it lucrative for domestic production, and overtaking India as the world's leading cotton supplier.[65] Western Europeans were also able to establish profitable trade with neighboring eastern Europeans. Countries such as Prussia, Bohemia, and Poland had very little freedoms in comparison to those to the west. Forced labor left much of Eastern Europe with little time to work towards proto-industrialization and ample manpower to generate raw materials. However, these areas were not large consumers of the Western Europe's manufactured products, leaving Western Europe to pay for much of its raw materials from eastern Europe.[66]

Timing

The timing of the Great Divergence is in dispute among historians. Many scholars put the date of the Great Divergence at 1800 or later, claiming that before that date the East, especially China, was more advanced.[21][20] Some other scholars put the date as early as the 16th century,[67] a claim disputed by other scholars citing nutrition and chronic western trade deficits as evidence that the date of 1800 or later as the date of the Great Divergence, dismissing claims of earlier dates as "Eurocentric".[21]

See also

- Colonial empire

- Western empires

- Modern history

- Second European colonization wave (19th century–20th century)

- Rise of the New Imperialism

- Economic history of China (pre-1911)

- Books

- Guns, Germs, and Steel

- The Civilizing Process

- The European Miracle

- The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community

- The Clash of Civilizations

References

- ^ a b c Frank 2001

- ^ a b Jones 2003

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, pp. 242–243

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, pp. 219–225

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, p. 219

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, p. 107

- ^ a b c Pomeranz 2000, p. 187

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, p. 241

- ^ Rothbard 2006, p. 213

- ^ Rothbard 2006, pp. 216, 221

- ^ Rothbard 2006, pp. 214–220

- ^ Rothbard 2006, p. 464

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, pp. 31–69

- ^ Myers & Wang 2002, pp. 564, 566

- ^ Myers & Wang 2002, p. 564

- ^ Myers & Wang 2002, p. 587

- ^ Myers & Wang 2002, pp. 587, 590

- ^ Myers & Wang 2002, p. 569

- ^ Myers & Wang 2002, p. 579

- ^ a b c Pomeranz 2000, p. 36

- ^ a b c d e Hobson 2004, p. 77

- ^ Hobson 2004, p. 76

- ^ a b Toynbee 1976, pp. 547–549

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 228–219

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 212-214

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 251

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 214

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 229

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clark & Feenstra 2003

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 65

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 62

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 62–66

- ^ Muller 2001, pp. 58–73

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 70

- ^ a b Pomeranz 2000, pp. 70–71

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 82

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 87, 196

- ^ Tan Ping, "The effect of Qing dynasty's view of governance on Sichuan", 1, November 30, 2006. Retrieved July 4, 2010

- ^ Gao Shenrong, Qing China's ecological characteristics and its expression, Xi'an University (2006), 1, retrieved July 7, 2010

- ^ Keliang 2003, p. 3

- ^ Ji & et al 2005, p. 63

- ^ Gao & Feng 2003, p. 321

- ^ Gao & Kuo 2007, p. 240

- ^ Xu 2005, p. 5-7

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 217

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 155

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 49

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 37

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 39

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 45–48

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 46

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 163

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 164

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 169

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 170

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 190

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 264

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, p. 266

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 7–8

- ^ Comin 2008

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 215–219

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 223–225

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 230–238

- ^ Williamson 2008, pp. 355–391

- ^ Broadberry & Gupta 2005

- ^ Pomeranz 2000, pp. 257–258

- ^ Maddison 2001, pp. 51–52[1]

Bibliography

- Broadberry, Stephen N.; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2005), "Cotton textiles and the great divergence: Lancashire, India and shifting competitive advantage, 1600–1850", International Macroeconomics and Economic History Initiative, Centre for Economic Policy Research

- Clark, Gregory; Feenstra, Robert C. (2003), "Technology in the Great Divergence", in Bordo, Michael D. (ed.), Globalization in Historical Perspective, University of Chicago Press, pp. 277–320, ISBN 978-0-226-06600-4

- Comin, Diego (2008), "Total Factor Productivity", [[The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics]] (PDF) (2nd ed.), Palgrave Macmillan, doi:10.1057/9780230226203.1719, ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Frank, Andre (2001), "Review of The Great Divergence", Journal of Asian Studies, 60 (1), Cambridge University Press: 180–182, doi:10.2307/2659525

- Gao; Feng (2003), Comparisons of Chinese and Japanese policies towards foreign commerce (in Chinese), Qinghua University Press, ISBN 9787302075172

- Gao; Kuo (2007), General History of China (in Chinese), Wunantu Publishing Firm, ISBN 9789571143125

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-54724-5

- Ji, Jianghong; et al. (2005), Encyclopedia of China History Vol 3 (in Chinese), Beijing publishing house, ISBN 7900321543

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - Jones, Eric (2003) [1st ed. 1981], The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52783-5

- Keliang, Lu (2003), "The reason for Yellow river flooding in near-Modern times" (PDF), Journal of Harbin University (in Chinese), 24 (11)

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Maddison, Angus (2001), The World Economy, Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective, OECD Publishing, ISBN 978-926418608-8

- Muller, Edward K. (2001), "Industrial Suburbs and the Growth of Metropolitan Pittsburgh, 1870–1920", Journal of Historical Geography, 27 (1): 58–73

- Myers, H. Ramon; Wang, Yeh-Chien (2002), "Economic developments, 1644–1800", in Peterson, Willard (ed.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9: The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 563–647, ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6

- Pomeranz, Kenneth (2000), The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-09010-8

- Rothbard, Murrary N. (2006), An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, ISBN 0-945466-48-X

- Toynbee, Arnold (1976), Mankind and Mother Earth, Oxford University Press

- Williamson, Jeffery G. (2008), "Globalization and the Great Divergence: terms of trade booms, volatility and the poor periphery, 1782–1913", European Review of Economic History, 12: 355–391, doi:10.1017/S136149160800230X

- Xu, Suming (2005), 1 The Great Divergence from a humanist perspective: Why was Jiangnan not England?, Tianjin Social Science

{{citation}}: Check|url=value (help)