The Tempest: Difference between revisions

→Date and Text: trying a shorter paragraph, but still as a seperate section. See discussion. |

nope |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Compared to many of Shakespeare's other plays, ''The Tempest'' relatively few textual problems. The text as we have it has a simple history, it was published in the [[First Folio]] in December 1623. In that volume, ''The Tempest'' is the first play in the section of Comedies, and therefore the opening play of the collection. This printing includes more stage directions than any of Shakespeare's other plays, although these directions seem to have been written more for a reader than for an actor. This leads scholars to infer that the editors of the First Folio, [[John Heminge]] and [[Henry Condell]], added the directions to the folio to aid the reader, and that they were not necessarily Shakespeare's original intent. Scholars have also wondered about the Masque in Act 4, which seems to have been added as an afterthought, possibly in honor of the wedding of [[Princess Elizabeth]] and Frederick in 1613. However, other scholars see this as unlikely, arguing that to take the Masque out of the play creates more problems than it solves.<ref>Coursen, 1-2</ref> |

Compared to many of Shakespeare's other plays, ''The Tempest'' relatively few textual problems. The text as we have it has a simple history, it was published in the [[First Folio]] in December 1623. In that volume, ''The Tempest'' is the first play in the section of Comedies, and therefore the opening play of the collection. This printing includes more stage directions than any of Shakespeare's other plays, although these directions seem to have been written more for a reader than for an actor. This leads scholars to infer that the editors of the First Folio, [[John Heminge]] and [[Henry Condell]], added the directions to the folio to aid the reader, and that they were not necessarily Shakespeare's original intent. Scholars have also wondered about the Masque in Act 4, which seems to have been added as an afterthought, possibly in honor of the wedding of [[Princess Elizabeth]] and Frederick in 1613. However, other scholars see this as unlikely, arguing that to take the Masque out of the play creates more problems than it solves.<ref>Coursen, 1-2</ref> |

||

===Dating and the authorship question=== |

|||

Dating of ''The Tempest'' has become a key battleground between mainstream scholars, and supporters of the alternate candidacy of [[Edward de Vere]], 17th Earl of Oxford, as the actual [[Shakespeare authorship question|writer of Shakespeare’s works.]] Mainstream scholars dismiss the [[Oxfordian theory|Oxford candidacy]], pointing to ''The Tempest'' as one of Shakespeare's plays that was written after Oxford’s death in 1604 and citing the [[Strachey]] report of 1610 as a source for the play. Oxfordian researchers<ref> Shakespeare and the Voyagers Revisited |

|||

Stritmatter and Kositsky Review of English Studies OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS,2007; 58: 447-472. http://www.shakespearefellowship.org/virtualclassroom/tempest/kositsky-stritmatter%20Tempest%20Table.htm </ref> and some orthodox scholars <ref>http://www.shaksper.net/archives/2001/0650.html</ref> challenge the Strachey assumption and counter that the common imagery between ''Strachey'' and ''The Tempest'' is due to common sources such as Ovid, Eden and Erasmus <ref>The research team of Stritmatter-Kositsky also asserts that Strachey's manuscript may not have been available until after mainstream scholars say ''The Tempest'' was first written noting that Strachey only reached England from the New World in late October/November of 1611, and his lengthly manuscript references more than a dozen outside sources including rare books that Strachey would have needed to wait until his return to England to consult;</ref>, and cite contemporary references which may date the play circa 1603-1605.<ref> and several plays from the earlier period "exhibit strong verbal or thematic similarities to ''The Tempest''."<ref> Mark Anderson notes that these plays include the Scots play Darius (by William Alexander, 1603), the Jacobean comedy Eastward Ho! (1605), and Die Schöne Sidea by the German playwright Jakob Ayrer (1604).</ref> |

|||

==List of characters== |

==List of characters== |

||

Revision as of 14:13, 13 November 2007

The Tempest is a play written by William Shakespeare. It is generally accepted to be Shakespeare's last play solely written by him.[1] Although listed as a comedy in the first Folio, many modern editors have relabelled the play a romance. First published in the First Folio of 1623, but generally dated to 1610-11, it did not attract a significant amount of attention before the closing of the theatres in 1642, and after the Restoration it attained great popularity only in adapted versions.[2] Theatre productions returned conclusively to the original Shakespearean text in the mid-nineteenth century.[3] In the twentieth century the play received a sweeping re-appraisal by critics and scholars, to the point that it is now considered one of Shakespeare's greatest works.[4]

Sources

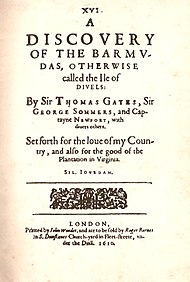

There is no obvious, single source for the plot of The Tempest. Instead, the play seems to have been created out of an amalgamation of sources.[5] Since source scholarship began in the eighteenth century, researchers have suggested that passages from Erasmus's Naufragium (The Shipwreck) (1523, English translation 1606) and Richard Eden's 1555 translation of Peter Martyr's De orbo novo, or Decades of the New Worlde Or West India (1530), influenced the composition of the play.[6] However, most Shakespearean scholars see parallel imagery in a work by William Strachey, an eyewitness report of the real-life shipwreck of the Sea Venture in 1609 on the islands of Bermuda while sailing toward Virginia. A character in the play makes reference to the still-vexed Bermoothes. Strachey's report was written in 1610; although it was not printed until 1625, it circulated in manuscript and many critics think that Shakespeare may have taken the idea of the shipwreck and some images from it. Another Sea Venture survivor, Sylvester Jordain, also published an account, A Discovery of The Barmudas, so the event would have been widely known. However, literary scholar Kenneth Muir believed that even though "[t]here is little doubt that Shakespeare had read . . . William Strachey's True Reportory of the Wracke" and other accounts, "[t]he extent of the verbal echoes of [the Bermuda] pamphlets has, I think, been exaggerated. There is hardly a shipwreck in history or fiction which does not mention splitting, in which the ship is not lightened of its cargo, in which the passengers do not give themselves up for lost, in which north winds are not sharp, and in which no one gets to shore by clinging to wreckage," and goes on to say that "Strachey's account of the shipwreck is blended with memories of St Paul's--in which too not a hair perished--and with Erasmus' colloquy."[7]

The overall form of the play is modelled heavily on traditional Italian commedia dell'arte performances, which sometimes featured a magus and his daughter, their supernatural attendants, and a number of rustics. The commedia often featured a clown-figure known as "Arlecchino" (or his predecessor, "Zanni") and his partner "Brighella," who bear a striking resemblance to Stephano and Trinculo; a lecherous Napolese hunch-back named "Pulcinella," who corresponds to Caliban; and the clever and beautiful "Isabella," whose wealthy and manipulative father, "Pantalone," constantly seeks a suitor for her, thus mirroring the relationship between Miranda and Prospero.[8]

In addition, one of Gonzalo's speeches is derived from On Cannibals, an essay by Montaigne that praises the society of the Caribbean natives "It is a nation ...that hath no kinde of traffike, no knowledge of letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politike superioritie; no use of service of riches, or of poverty; no contracts, no successions, no dividences, no ocupation but idle; no respect of kinred, but common, no apparrell but naturall, no manuring of lands, no use of wine corne, or mettle. The very words that import lying, falsehood, treason, dissimulation, covetousnes, envie, detraction, and pardon, were never heard of amongst them."[9][10] and much of Prospero's renunciative speech is taken word for word from a speech by Medea in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[11]

The play draws heavily from the tradition of the Romance, which featured a fictitious narrative set far away from ordinary life. Romances were typically based around themes such as the supernatural, wandering, exploration and discovery. Romances were often set in coastal regions, and typically featured exotic, fantastical locations; they featured themes of transgression and redemption, loss and retrieval, exile and reunion. As a result, while The Tempest was originally listed as a comedy in the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays, subsequent editors have chosen to give it the more specific label of Shakespearean romance. Like the other romances, the play was influenced by the then-new genre of tragicomedy, introduced by John Fletcher in the first decade of the seventeenth century and developed in the Beaumont and Fletcher collaborations, as well as by the explosion of development in the courtly masque being conducted by Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones at the same time.[citation needed]

Date and Text

The Tempest is generally accepted to be Shakespeare's last play solely written by him,[12] although some scholars point out that it is impossible to determine if it was written before, after or at the same time as The Winter's Tale.[13] Generally dated to 1610-11, the play was entered into the Stationers' Register by Edward Blount on November 8, 1623. It was one of sixteen Shakespearean plays Blount registered on that date.

Compared to many of Shakespeare's other plays, The Tempest relatively few textual problems. The text as we have it has a simple history, it was published in the First Folio in December 1623. In that volume, The Tempest is the first play in the section of Comedies, and therefore the opening play of the collection. This printing includes more stage directions than any of Shakespeare's other plays, although these directions seem to have been written more for a reader than for an actor. This leads scholars to infer that the editors of the First Folio, John Heminge and Henry Condell, added the directions to the folio to aid the reader, and that they were not necessarily Shakespeare's original intent. Scholars have also wondered about the Masque in Act 4, which seems to have been added as an afterthought, possibly in honor of the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick in 1613. However, other scholars see this as unlikely, arguing that to take the Masque out of the play creates more problems than it solves.[14]

List of characters

- Alonso, King of Naples

- Sebastian, Alonso's brother

- Prospero, the rightful Duke of Milan and the story's protagonist

- Antonio, his brother, the usurping Duke of Milan

- Ferdinand, son of the King of Naples (Alonso)

- Gonzalo, an honest, optimistic old councilor who gave Prospero food, water, and books.

- Adrian and Francisco, lords

- Caliban, deformed slave of Prospero and son of Sycorax

- Trinculo, a jester

- Stephano, a drunken butler (sometimes Stefano)

- Miranda, daughter of Prospero, often called "a wonder"

- Ariel, an airy spirit

- Boatswain

- Sycorax, witch and mother of Caliban (but does not appear in the play)

- Iris, Ceres and Juno, spirits

Synopsis

The sorcerer Prospero, rightful Duke of Milan, and his daughter, Miranda, have been stranded for twelve years on an island, after Prospero's jealous brother Antonio—helped by Alonso, the King of Naples—deposed him and set him adrift with the three-year-old Miranda. Prospero secretly sought the help of Gonzalo and their small and shoddy boat had secretly been upgraded to be more than sea worthy, it had been supplied with plenty of food and water, it had an excellent library and contained surviving material in case the boat capsized. Possessed of magic powers due to his great learning and prodigious library, Prospero is reluctantly served by a spirit, Ariel whom he had rescued from imprisonment in a tree. Ariel was trapped therein by the African witch Sycorax, who had been exiled to the island years before and died prior to Prospero's arrival; Prospero maintains Ariel's loyalty by repeatedly promising to release the "airy spirit" from servitude, but continually defers that promise to a future date, namely at the end of the play. The witch's son Caliban, a deformed monster and the only non-spiritual inhabitant before the arrival of Prospero, was initially adopted and raised by the Milanese sorcerer. He taught Prospero how to survive on the island, while Prospero and Miranda taught Caliban religion and their own language. Following Caliban's attempted rape of Miranda, he had been compelled by Prospero to serve as the sorcerer's slave, carrying wood and gathering pig nuts. In slavery Caliban has come to view Prospero as an usurper, and grown to resent the magician and his daughter, feeling that they have betrayed his trust. Prospero and Miranda in turn view Caliban with contempt and disgust.

The play opens as Prospero, having divined that his brother, Antonio, is on a ship passing close by the island (having returned from the nuptials of Alonso's daughter Claribel with the King of Tunis), has raised a storm (the tempest of the title) which causes the ship to run aground. Also on the ship are Antonio's friend and fellow conspirator, King Alonso, Alonso's brother Sebastian, Alonso's royal advisor Gonzalo, and Alonso's son, Ferdinand. Prospero, by his spells, contrives to separate the survivors of the wreck into several groups and Alonso and Ferdinand are separated, and believe one another dead.

Three plots then alternate through the play. In one, Caliban falls in with Stephano and Trinculo, two drunken crew members, whom he believes to have come from the moon, and drunkenly attempt to raise a rebellion against Prospero (which ultimately fails). In another, Prospero works to establish a romantic relationship between Ferdinand and Miranda; the two fall immediately in love, but Prospero worries that "too light winning [may] make the prize light", and so compels Ferdinand to become his servant so that his affection for Miranda will be confirmed. He also decides that after his plan to exact vengeance on his betrayers has come to fruition, he will break and bury his staff, and "drown" his book of magic. In the third subplot, Antonio and Sebastian conspire to kill Alonso and his advisor Gonzalo, so that Sebastian can become King. They are thwarted by Ariel, at Prospero's command. Ariel appears to the three "men of sin" as a harpy, reprimanding them for their betrayal of Prospero. Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio are deeply affected while Gonzalo is unruffled. Prospero manipulates the course of his enemies' path through the island, drawing them closer and closer to him. In the conclusion, all the main characters are brought together before Prospero, who forgives Alonso (as well as his own brother's betrayal, and warns Antonio and Sebastian about further attempts at betrayal) and finally uses his magic to ensure that everyone returns to Italy.

Ariel (as his final task for Prospero) is charged to prepare the proper sailing weather to guide Alonso and his entourage back to the Royal fleet and then to Naples. Ariel is set free to the elements. Prospero pardons Caliban who is sent to prepare Prospero’s cell, to which Alonso and his party are invited for a final night before their departure. Prospero indicates he intends to entertain them with the story of his life on the island. In his epilogue, Prospero invites the audience to set him free from the island by their applause.

Criticism and Analysis

Themes

Focusing on Prospero's evocative surrender of magic in the play's final scene, traditional critics regularly offered an impressionistic and subjectivist interpretation of the play as Shakespeare's "farewell to the stage" preceding his retirement – though it is certainly not his "final play", as has sometimes been claimed. The available evidence indicates that Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen were written later, though both are regarded as collaborations.

One author notes: "Why Shakespeare observed the three unities in The Tempest is not known. In most of his other plays, events occur on several days and characters visit numerous settings. Some scholars have suggested that, because The Tempest contains so much fantasy, Shakespeare may have wanted to observe the unities to help audiences suspend their disbelief. Others have pointed to criticism that Shakespeare received for ignoring the unities; they say he may have wanted to prove once and for all that he could follow rules if he felt like it."[15]

This section possibly contains original research. (October 2007) |

Kingships

The concept of usurping a monarch occurs frequently throughout the play: Antonio usurped Prospero; Caliban accuses Prospero of having usurped him upon the latter's arrival on the island; Sebastian plots to kill and overthrow his brother the King of Naples; Stephano has designs to depose Prospero and set himself up as "king o'the isle." As such, the play is simultaneously concerned with what constitutes virtuous kingship, presenting the audience with various possibilities. In the twentieth century, post-colonial literary critics were extremely interested in this aspect of the play, seeing Caliban as representative of the natives invaded and oppressed by imperialism.

The themes of political legitimacy, source of power, and usurpation arise in the second act as well. While Prospero firmly believed that the only legitimate power was the power that came from one's knowledge and hard work, Antonio believes that the power he usurped from his brother is legitimate, because he deserved it more and had the skill to wrestle it away. "Look how well my garments sit upon me, much feater than before," Antonio brags to Sebastian; Antonio's lack of remorse over his crime, and his arrogant claim that his power is just because he uses it better, foreshadow a confrontation with his brother Prospero, and an eventual fall from this ill-gained power.

Although Caliban asserted his natural authority over the island in Act 1, Prospero's usurpation of Caliban's power is negated by Caliban's portrayal as a savage seeking a new master. Caliban proves Prospero's view of him, as a natural servant, to be true, when Caliban immediately adopts Stephano as his new master upon Stephano's sudden appearance. Caliban, is seen as a "monster," not only by Prospero, but by Trinculo and Stephano also; modern interpretations cast their contempt for dark-skinned Caliban as analogous to Europeans' view of "natives" in the West Indies and other colonies, and Shakespeare's treatment of Caliban has come to provide some interesting social commentary on colonization although it is unlikely that Shakespeare's contemporary audiences viewed the character in this way and debatable as to the author's original intent. Caliban's actions and activities lend credence to the view that the original intent was for more of a thematic monster than an allegorical figure.

The theatre

The Tempest is overtly concerned with its own nature as a play, frequently drawing links between Prospero's Art and theatrical illusion. The shipwreck was a "spectacle" "performed" by Ariel; Antonio and Sebastian are "cast" in a "troop" to "act"; Miranda's eyelids are "fringed curtains". Prospero is even made to refer to the Globe Theatre when claiming the whole world is an illusion: "the great globe... shall dissolve... like this insubstantial pageant". Ariel frequently disguises himself as figures from Classical mythology, for example a nymph, a harpie and Ceres, and acts as these in a masque and anti-masque that Prospero creates.

Early critics saw this constant allusion to the theatre as an indication that Prospero was meant to represent Shakespeare; the character's renunciation of magic thus signalling Shakespeare's farewell to the stage. This theory has fallen into disfavour; but certainly The Tempest is interested in the way that, like Prospero's "Art", the theatre can be both an immoral occupation and yet morally transformative for its audience.

Magic

Magic is a pivotal theme in the Tempest, as it is the device that holds the plot together. Prospero commands so much power in the play because of his ability to use magic and to control the spirit Ariel, and with magic, he creates the tempest itself, as well as controlling all the happenings on the island, eventually bringing all his old enemies to him to be reconciled. Magic is also used to create a lot of the imagery in the play, with scenes such as the masque, the opening scene, and the enchanting music of Ariel. It is also believed that magic may in fact refer to Shakespeare's writing, hence the "drown[ing]" of the magic book can be interpreted as Shakespeare retiring his play writing.

Critical approaches

Postcolonialist

In Shakespeare's day, most of the world was still being "discovered", and stories were coming back from far off Islands, with myths about the Cannibals of the Caribbean, faraway Edens, and distant Tropical Utopias. With the character Caliban (whose name is roughly anagrammatic to Cannibal), Shakespeare may be offering an in-depth discussion into the morality of colonialism. Different views are discussed, with examples including Gonzalo's Utopia, Prospero's enslavement of Caliban and Caliban's resentment of this. Caliban is also shown as one of the most natural characters in the play, being very much in touch with the natural world (and modern audiences have come to view him as far nobler than his two Old World friends Stephano and Trinculo, although the original intent of the author may have been different). There is evidence that Shakespeare drew on Montaigne's essay Of Cannibals, which discusses the values of societies insulated from European influences, while writing The Tempest.[16]

Beginning in about 1950, with the publication of Psychology of Colonization by Octave Mannoni, The Tempest was viewed more and more through the lens of postcolonial theory. This new way of looking at the text explored the effect of the colonizer (Prospero) on the colonized (Ariel and Caliban). Though Ariel is often overlooked in these debates in favor of the more intriguing Caliban, he is still involved in many of the debates.[17] The French writer Aimé Césaire, in his play Une Tempête sets The Tempest in Haiti, portraying Ariel as a mulatto who, unlike the more rebellious Caliban, feels that negotiation and partnership is the way to freedom from the colonizers. Fernandez Retamar sets his version of the play in Cuba, and portrays Ariel as a wealthy Cuban (in comparison to the lower-class Caliban) who also must choose between rebellion or negotiation.[18] Although scholars have suggested that his dialogue with Caliban in Act two, Scene one, contains hints of a future alliance between the two when Prospero leaves, in general, Ariel is viewed by scholars as the good servant, in comparison with the conniving Caliban—a view which Shakespeare's audience would have shared.[19] Ariel is used by some postcolonial writers as a symbol of their efforts to overcome the effects of colonization on their culture. Michelle Cliff, for example, a Jamaican author, has said that she tries to combine Caliban and Ariel within herself to create a way of writing that represents her culture better. Such use of Ariel in postcolonial thought is far from uncommon, as Ariel is even the namesake of a scholarly journal covering post-colonial criticism.[17]

Performance history

The first recorded performance of The Tempest occurred on November 1, 1611, when the King's Men acted the play before James I and the English royal court at Whitehall Palace on Hallowmas night. It was also one of the eight Shakespearean plays acted at Court during the winter of 1612–13, as part of the festivities surrounding the marriage of Princess Elizabeth with Frederick V, the Elector of the Palatinate in the Rhineland.[20] There is no public performance recorded prior to the Restoration; but in his preface to the 1667 Dryden/Davenant version (see Adaptations below), Sir William Davenant states that The Tempest had been performed at the Blackfriars Theatre. Careful consideration of stage directions within the play supports this, strongly suggesting that the play was written with Blackfriars Theatre rather than the Globe Theatre in mind.[21]

William Charles Macready staged an influential production of the original text in 1838, which helped to kill off the adapted and operatic versions popular for most of the previous two centuries. Charles Kean's massive production of 1857, which needed 140 stagehands to manage its scenery and effects, set a pattern for increasingly elaborate productions in the Victorian era, which tended to feature less and less of Shakespeare's text. The next generation of producers, which included William Poel and Harley Granville-Barker, returned to a leaner and more text-based style.[22]

The most famous Prospero in history is John Gielgud, who called it his favorite role, and played it in stage productions in 1931, 1940, 1957 and 1974 as well as the film Prospero's Books. He said that when he played it on stage, the only thing that he did consistently in all four theatre productions was never to look directly at Ariel.[23] Other notable Prosperos include Michael Redgrave for the Royal Shakespeare Company and Patrick Stewart, who has played the role both for the RSC and on Broadway.

Famous Calibans include Canada Lee, who played the role in Margaret Webster's 1945 production co-starring Arnold Moss as Prospero that ran for 100 performances, the longest Broadway run of the play in history. Ralph Richardson played the part as a Mongolian monster in 1931 at the Old Vic Theatre, and James Earl Jones played Caliban successfully at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1962 . Frank Benson's Caliban was famous for his hanging upside-down in a tree with a fish in his mouth.[24]

Adaptations

- See also Shakespeare on screen (The Tempest).

Sir William Davenant and John Dryden adapted a deeply cut version of The Tempest, "corrected" for Restoration audiences and adorned with music set by Matthew Locke, Giovanni Draghi, Pelham Humfrey, Pietro Reggio, James Hart and John Banister. Dryden and Davenant added characters and plotlines and removing much of the play's "mythic resonance". Dryden's remarks in the Preface to his opera Albion and Albanius give an indication of the struggle later 17th century critics had with the elusive masque-like character of a play that fit no preconceptions. Albion and Albinius was first conceived as a prologue to the adapted Shakespeare (in 1680), then extended into an entertainment on its own. In Dryden's view, The Tempest

"...is a tragedy mixed with opera, or a drama, written in blank verse, adorned with scenes, machines, songs, and dances, so that the fable of it is all spoken and acted by the best of the comedians... It cannot properly be called a play, because the action of it is supposed to be conducted sometimes by supernatural means, or magic; nor an opera, because the story of it is not sung." (Dryden, Preface to Albion and Albinius).

In 1674, Thomas Shadwell re-adapted Dryden and Davenant's adaptation, with music by Henry Purcell. Though Shakespeare's original text was mounted at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1746, David Garrick staged another operatic version ten years later (1756), with music by John Christopher Smith. Frederic Reynolds produced yet another operatic version in 1821, with music by Sir Henry Bishop.[25]

The Tempest has inspired numerous later works, including short poems such as "Caliban Upon Setebos" by Robert Browning, and the long poem The Sea and the Mirror by W. H. Auden. The title of the novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley is also taken explicitly from Miranda's dialogue in this play:

- O, wonder!

- How many goodly creatures are there here!

- How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world

- That has such people in't! (V.i.181-4)

References

Notes

- ^ Barton,22; Vauhgan and Vaughan, 1; deGrazia and Wells, xx.

- ^ Orgel, 64-68

- ^ Orgel, p. 68

- ^ Frye, p. 24

- ^ Coursen, 7

- ^ (Eden: Kermode 1958 xxxii-xxxiii; Erasmus: Bullough 1975 VIII: 334-339)

- ^ The Sources of Shakespeare's Plays, New Haven: Yale University Press (1978), p. 280

- ^ Coursen, 13

- ^ Montaigne, 102

- ^ Coursen, 11-12

- ^ Gilman, Ernest B. "'All eyes': Prospero's Inverted Masque." Renaissance Quarterly. (July 1980) 33.2 pgs. 214-230

- ^ Barton,22; Vauhgan and Vaughan, 1; deGrazia and Wells, xx.

- ^ Orgel, 63-64. Dating of The Winter's Tale has been equally problematic - According to Dr. Samuel A. Tannenbaum in Shaksperian Scraps, chapter: "The Forman Notes" (1933), "scholars had been disputing for considerably more than half a century whether The Winter's Tale was one of Shakespeare's earliest plays or one of his latest." Tannenbaum reports that "Malone had at first decided that it was written in 1594; subsequently he seems to have assigned it to 1604; later still, to 1613; and finally he settled on 1610-11. Hunter assigned it to about 1605."

- ^ Coursen, 1-2

- ^ http://www.glencoe.com/sec/literature/litlibrary/pdf/tempest.pdf

- ^ Carey-Webb, Allen. "Shakespeare for the 1990s: A Multicultural Tempest." The English Journal. (Apr 1993) 82.4 pgs. 30-35

- ^ a b Cartelli, Thomas. "After 'The Tempest:' Shakespeare, Postcoloniality, and Michelle Cliff's New, New World Miranda." Contemporary Literature. (Apr 1995) 36.1 pgs. 82-102

- ^ Nixon, Rob. "Caribbean and African Appropriations of 'The Tempest'." Critical Inquiry. (Apr 1987) 13.3 pgs. 557-578

- ^ Dolan, Frances E. "The Subordinate('s) Plot: Petty Treason and the Forms of Domestic Rebellion." Shakespeare Quarterly. (Oct 1992) 43.3 pgs. 317-340

- ^ Halliday, p. 486.

- ^ Andrew Gurr, " The Tempest's Tempest at Blackfriars", Shakespeare Survey 41, Cambridge University Press, 1989; p. 91-102.

- ^ Halliday, pp. 486-7.

- ^ John Gielgud, Acting Shakespeare, Charles Scribner's Sons (1991)

- ^ John Gielgud, Acting Shakespeare, Charles Scribner's Sons (1991)

- ^ Halliday, pp. 410, 486.

Editions of The Tempest

- Barton, Anne, ed. 1968. The Tempest New York: Penguin.

- Frye, Northrop, ed. 1970. The Tempest. New York: Penguin.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. 1987. The Tempest. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0192834142

- Vaughan, Virginia Mason and Alden T. Vaughan, eds. 1999. The Tempest London: Arden Third Series. ISBN 0174435355

Secondary sources

- Barton, Anne ed. 1968. The Tempest. New York: Penguin.

- Coursen, Herbert. The Tempest. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0313311919

- de Grazia, Margreta and Stanley Wells, eds. 2001. "Conjectural Chronology of Shakespeare's Works". The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frye, Northrop, ed. 1970. The Tempest. New York: Penguin.

- Halliday, F. E. 1964. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin.

- McCollum, John I. Jr. The Restoration Stage. Houghton Mifflin Research Series, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Riverside Press, 1961.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. 1987. The Tempest. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0192834142

- Vaughan, Virginia Mason and Alden T. Vaughan, eds. 1999. The Tempest London: Arden. ISBN 0174435355

Further reading

- Gerald Graff and James Phelan, The Tempest: A Case Study in Critical Controversy, London, MacMillan, 2000

- Frances A. Yates, Shakespeare's Last Plays: A New Approach, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975

- Frances A. Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

- Shakespeare's The Tempest: The Wise Man as Hero

- The Theme of Natural Order in "The Tempest"

- Form and Disorder in The Tempest

- The Magic of Charity: A Background to Prospero

External links

- The Tempest - plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

- The Tempest - scene indexed, online version of the play.

- The Tempest - HTML version of this title.

- Bermoothes in E. Cobham Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898).

- Lesson plans for The Tempest at Web English Teacher

- William Strachey's "True Reportory" original-spelling version at Virtual Jamestown.