(532037) 2013 FY27

2013 FY27 and its satellite, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope on 15 January 2018 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | |

| Discovery date | 17 March 2013 (announced on 31 March 2014) |

| Designations | |

| 2013 FY27 | |

| Orbital characteristics[3] | |

| Epoch 2023 Feb 25 (JD 2460000.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 4 | |

| Observation arc | 3953 days (10.82 yr) |

| Earliest precovery date | 15 March 2011 (Pan-STARRS) |

| Aphelion | 81.912 AU (12.2539 Tm) |

| Perihelion | 35.199 AU (5.2657 Tm) |

| 58.555 AU (8.7597 Tm) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.3989 |

| 448.08 yr (163,660 d) | |

| 215.947° | |

| 0° 0m 7.92s /day | |

| Inclination | 33.290° |

| 186.922° | |

| ≈ 2202 June 15 ± 17 days | |

| 139.752° | |

| Known satellites | 1[4][5][6] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 765+80 −85 km (effective diameter)[4] 742+78 −83 km (primary)[a][4] | |

| 0.170+0.045 −0.030[4] | |

| Temperature | 22 K (perihelion) to 16 K (aphelion) |

| |

| 22.5[7] | |

| 3.15±0.03[4][3] | |

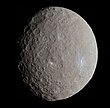

(532037) 2013 FY27 (provisional designation 2013 FY27) is a trans-Neptunian object and binary system that belongs to the scattered disc (like Eris).[8] Its discovery was announced on 31 March 2014.[1] It has an absolute magnitude (H) of 3.2.[3] 2013 FY27 is a binary object, with two components approximately 740 kilometres (460 mi) and 190 kilometres (120 mi) in diameter. It is the ninth-intrinsically-brightest known trans-Neptunian object,[9][failed verification] and is approximately tied with 2002 AW197 and 2002 MS4 (to within measurement uncertainties) as the largest unnamed object in the Solar System.

Orbit

[edit]

2013 FY27 orbits the Sun once every 449 years. It will come to perihelion around November 2202,[3][b] at a distance of about 35.6 AU. It is currently near aphelion, 80 AU from the Sun, and, as a result, it has an apparent magnitude of 22.[1] Its orbit has a significant inclination of 33°.[3] The sednoid 2012 VP113 and the scattered-disc object 2013 FZ27 were discovered by the same survey as 2013 FY27 and were announced within about a week of one another.

Physical properties

[edit]2013 FY27 has a diameter of about 740 kilometres (460 mi), placing it at a transition zone between medium-sized and large TNOs. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array and Magellan Telescopes, its albedo was found to be 0.17, and its colour to be moderately red. 2013 FY27 is one of the largest moderately red TNOs. The physical processes that lead to a lack of such moderately red TNOs larger than 800 kilometres (500 mi) are not yet well understood.

The brightness of 2013 FY27 varies by less than 0.06 mag over hours and days, suggesting that it either has a very long rotation period, an approximately spheroidal shape, or a rotation axis pointing towards Earth.[4]

Brown estimated, prior to the discovery of its satellite, that 2013 FY27 was very likely to be a dwarf planet, due to its large size.[10] However, Grundy et al. calculate that bodies such as 2013 FY27, less than about 1000 km in diameter, with albedos less than ≈0.2 and densities of ≈1.2 g/cm3 or less, may retain a degree of porosity in their physical structure, having never collapsed into fully solid bodies.[11]

The surface area of asteroid 532037 (2013 FY27) is similar to the area of the state of Texas. [12]

Satellite

[edit] Animation of 2013 FY27 and its satellite, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope from January to July 2018 | |

| Discovery[4] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by |

|

| Discovery date | 15 January 2018 |

| Orbital characteristics[4] | |

| >9800±40 km | |

| ≈19 d (for assumed density 1.6 g/cm3)[13] | |

| Satellite of | 2013 FY27 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| ≈186 km (assuming equal albedos)[4] | |

| Albedo | 0.170+0.045 −0.030 (assumed) |

| 25.5[7] | |

| 6.15[c] | |

Using Hubble Space Telescope observations taken in January 2018, Scott Sheppard found a satellite around 2013 FY27, that was 0.17 arcseconds away and 3.0±0.2 mag fainter than its primary. The discovery was announced on 10 August 2018.[14] The satellite does not have a provisional designation nor a proper name.[3] Assuming the two components have equal albedos, they are about 742+78

−83 km and 186±20 km in diameter, respectively.[4] Follow-up observations were taken between May and July 2018 in order to determine the orbit of the satellite,[5] but the results of these observations remain yet to be published as of 2022[update].[7] Once the orbit is known, the mass of the system can be determined.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Assuming the two components have equal albedos

- ^ The uncertainty in the time of perihelion passage is ≈1 month (1-sigma) or 3.6 months (3-sigma).[3]

- ^ Given the primary's absolute magnitude of H = 3.15 and a magnitude difference of Δm = 3.00 between the primary and satellite, the sum of those magnitudes is the satellite's absolute magnitude, 6.15.[4][7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "MPEC 2014-F82 : 2013 FY27". IAU Minor Planet Center. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2018. (K13F27Y)

- ^ "List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2013 FY27)" (last observation: 2022-01-09; arc: 10.82 years). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sheppard, Scott; Fernandez, Yanga; Moullet, Arielle (6 September 2018). "The Albedos, Sizes, Colors and Satellites of Dwarf Planets Compared with Newly Measured Dwarf Planet 2013 FY27". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (6): 270. arXiv:1809.02184. Bibcode:2018AJ....156..270S. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aae92a. S2CID 119522310.

- ^ a b Scott Sheppard (21 March 2018). "The Orbit of the Newly Discovered Satellite around the Dwarf Planet 2013 FY27 - HST Proposal 15460". Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Scott Sheppard (7 April 2017). "A Satellite Search of a Newly Discovered Dwarf Planet – HST Proposal 15248". Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d Grundy, Will (21 March 2022). "532037 (2013 FY27)". Lowell Observatory. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (2 April 2014). "More excitement in the outermost solar system: 2013 FY27, a new dwarf planet". www.planetary.org/blogs. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: orbital class (TNO) and H < 3.2 (mag)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Mike Brown, How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system? Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine (assumes H = 3.3)

- ^ W.M. Grundy, K.S. Noll, M.W. Buie, S.D. Benecchi, D. Ragozzine & H.G. Roe, 'The Mutual Orbit, Mass, and Density of Transneptunian Binary Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà ((229762) 2007 UK126)', Icarus [1] Archived 7 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.037,

- ^ https://www.spacereference.org/asteroid/532037-2013-fy27

- ^ Johnston, Wm. Robert (27 May 2019). "(532037) 2013 FY27". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Green, Daniel W. E. (10 August 2018). "CBET 4537: 2013 FY27". Central Bureau Electronic Telegram. Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

External links

[edit]- 2013 FY27, Minor planets with Satellites Database, Johnston's Archive

- Celestia Files of the recent Dwarf Planet finds (Ian Musgrave: 6 April 2014)

- Gaggle of dwarf planets found by Dark Energy Camera (Aviva Rutkin: 2 April 2014)

- (532037) 2013 FY27 at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- (532037) 2013 FY27 at the JPL Small-Body Database