Stalker (1979 film)

| Stalker | |

|---|---|

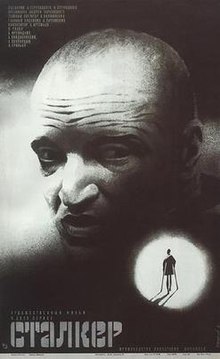

Original release poster | |

| Directed by | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Written by | Boris Strugatsky Arkady Strugatsky| Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Based on | Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky |

| Produced by | Aleksandra Demidova[n 1] |

| Starring | Alexander Kaidanovsky Anatoly Solonitsyn Nikolai Grinko Alisa Freindlich |

| Cinematography | Alexander Knyazhinsky |

| Edited by | Lyudmila Feiginova |

| Music by | Eduard Artemyev |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Goskino |

Release dates | |

Running time | 161 minutes[3] |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Budget | 1 million SUR[2] |

| Box office | 4.3 million tickets[4] |

Stalker (Russian: Сталкер, IPA: [ˈstaɫkʲɪr]) is a 1979 Soviet science fiction art drama film directed by Andrei Tarkovsky with a screenplay written by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, loosely based on their 1972 novel Roadside Picnic. The film combines elements of science fiction with dramatic philosophical and psychological themes.[5]

The film tells the story of an expedition led by a figure known as the "Stalker" (Alexander Kaidanovsky), who takes his two clients—a melancholic writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn) seeking inspiration, and a professor (Nikolai Grinko) seeking scientific discovery—to a mysterious restricted site known simply as the "Zone", where there supposedly exists a room which grants a person's innermost desires.

Stalker was released on Goskino in May 1979. Upon release, the film garnered mixed reviews initially before receiving overwhelmingly positive reviews over the following years, thus becoming a cult film with many praising Tarkovsky's directing, visuals, themes and screenwriting. The film grossed over 4 million worldwide, mostly in the Soviet Union, against a budget of 1 million Soviet rubles.[citation needed]

Title

The meaning of the word "stalk" was derived from its use by the Strugatsky brothers in their novel Roadside Picnic, upon which the movie is based. In Roadside Picnic, "Stalker" was a common nickname for men engaged in the illegal enterprise of prospecting for and smuggling alien artifacts out of the "Zone". The common English definition of the term "stalking" was also cited by Andrei Tarkovsky.[6]

In the film, a "stalker" is a professional guide to the Zone, someone having the ability and desire to cross the border into the dangerous and forbidden place with a specific goal.[5][7]

Plot

This section possibly contains original research. (June 2020) |

In the distant future, the protagonist (Alexander Kaidanovsky) works in an unnamed location as a "Stalker" who leads people through the "Zone", an area in which the normal laws of reality do not apply and remnants of seemingly extraterrestrial activity lie undisturbed among its ruins. The Zone contains a place called the "Room", said to grant the wishes of anyone who steps inside. The area containing the Zone is shrouded in secrecy, sealed off by the government and surrounded by ominous hazards.

At home with his wife and daughter, the Stalker's wife (Alisa Freindlich) begs him not to go into the Zone, but he dismissively rejects her pleas. In a rundown bar, the Stalker meets his next clients for a trip into the Zone, the Writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn) and the Professor (Nikolai Grinko).

They evade the military blockade that guards the Zone by following a train inside the gate and ride into the heart of the Zone on a railway work car. The Stalker tells his clients they must do exactly as he says to survive the dangers which lie ahead and explains that the Zone must be respected and the straightest path is not always the shortest path. The Stalker tests for various "traps" by throwing metal nuts tied to strips of cloth ahead of them. He refers to a previous Stalker named "Porcupine", who had led his brother to his death in the Zone, visited the Room, come into possession of a large sum of money, and shortly afterwards committed suicide. The Writer is skeptical of any real danger, but the Professor generally follows the Stalker's advice.

As they travel, the three men discuss their reasons for wanting to visit the Room. The Writer expresses his fear of losing his inspiration. The Professor seems less anxious, although he insists on carrying along a small backpack. The Professor admits he hopes to win a Nobel Prize for scientific analysis of the Zone. The Stalker insists he has no motive beyond the altruistic aim of aiding the desperate to their desires.

After traveling through the tunnels, the three finally reach their destination: a decayed and decrepit industrial building. In a small antechamber, a phone rings. The surprised Professor decides to use the phone to telephone a colleague. As the trio approach the Room, the Professor reveals his true intentions in undertaking the journey. The Professor has brought a 20-kiloton bomb (comparable to the Nagasaki nuclear bomb) with him, and he intends to destroy the Room to prevent its use by evil men. The three men enter a physical and verbal standoff just outside the Room that leaves them exhausted.

The Writer realizes that when Porcupine met his goal, despite his conscious motives, the room fulfilled Porcupine's secret desire for wealth rather than bring back his brother from death. This prompted the guilt-ridden Porcupine to commit suicide. The Writer tells them that no one in the whole world is able to know their true desires and as such it is impossible to use the Room for selfish reasons. The Professor gives up on his plan of destroying the Room. Instead, he disassembles his bomb and scatters its pieces. No one attempts to enter the Room.

The Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor are met back at the bar by the Stalker's wife and daughter. After returning home, the Stalker tells his wife how humanity has lost its faith and belief needed for both traversing the Zone and living a good life. As the Stalker sleeps, his wife contemplates their relationship in a monologue delivered directly to the camera. In the last scene Martyshka, the couple's deformed daughter, sits alone in the kitchen reading as a love poem by Fyodor Tyutchev is recited. She appears to use psychokinesis to push three drinking glasses across the table. A train passes by where the Stalker's family lives, and the entire apartment shakes.

Cast

- Alexander Kaidanovsky as the Stalker

- Anatoly Solonitsyn as the Writer

- Alisa Freindlich as the Stalker's wife

- Nikolai Grinko as the Professor (voiced by Sergei Yakovlev)

- Natasha Abramova as Martyshka, the Stalker's daughter

- Faime Jurno as the Writer's girlfriend

- E. Kostin as Lyuger, the bar owner

- Raymo Rendi as the patrolman

- Vladimir Zamansky as the voice on the phone conversation with the Professor

Themes and interpretations

There are several interpretations of the film.

Geoff Dyer claims the Stalker is "seeking asylum from the world".[8] Dyer says "while the film may not be about the gulag, it is haunted by memories of the camps, from the overlap of vocabulary ("Zona", "the meat grinder") to the Stalker's Zek-style shaved head."[8]

Multiple people have compared the film to The Wizard of Oz (1939 film).[8][9]

Production

Writing

After reading the novel, Roadside Picnic, by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Tarkovsky initially recommended it to a friend, the film director Mikhail Kalatozov, thinking Kalatozov might be interested in adapting it into a film. Kalatozov abandoned the project when he could not obtain the rights to the novel. Tarkovsky then became very interested in adapting the novel and expanding its concepts. He hoped it would allow him to make a film which conforms to the classical Aristotelian unity; a single action, on a single location, within 24 hours (single point in time).[7]

Tarkovsky viewed the idea of the Zone as a dramatic tool to draw out the personalities of the three protagonists, particularly the psychological damage from everything that happens to the idealistic views of the Stalker as he finds himself unable to make others happy:

"This, too, is what Stalker is about: the hero goes through moments of despair when his faith is shaken; but every time he comes to a renewed sense of his vocation to serve people who have lost their hopes and illusions."[10]

The film departs considerably from the novel. According to an interview with Tarkovsky in 1979, the film has basically nothing in common with the novel except for the two words "Stalker" and "Zone".[7]

Yet, several similarities remain between the novel and the film. In both works, the Zone is guarded by a police or military guard, apparently authorized to use deadly force. The Stalker in both works tests the safety of his path by tossing nuts and bolts tied with scraps of cloth, verifying that gravity is working as usual. A character named Porcupine is a mentor to Stalker. In the novel, frequent visits to the Zone increase the likelihood of abnormalities in the visitor's offspring. In the book, the Stalker's daughter has light hair all over her body, while in the film she is crippled and has psychokinetic abilities. The 'meat grinder', a particularly perilous location, is mentioned in both film and the book. Neither in the novel nor in the film do the women enter the Zone. Finally, the target of the expedition in both works is a wish-granting device.[citation needed]

In Roadside Picnic, the site was specifically described as the site of alien visitation; the name of the novel derives from a metaphor proposed by a character who compares the visit to a roadside picnic. The closing monologue by the Stalker's wife at the end of the film has no equivalent in the novel. An early draft of the screenplay was published as a novel Stalker that differs substantially from the finished film.[citation needed]

Production

In an interview on the MK2 DVD, the production designer, Rashit Safiullin, recalled that Tarkovsky spent a year shooting a version of the outdoor scenes of Stalker. However, when the crew returned to Moscow, they found that all of the film had been improperly developed and their footage was unusable. The film had been shot on new Kodak 5247 stock with which Soviet laboratories were not very familiar.[11] Even before the film stock problem was discovered, relations between Tarkovsky and Stalker's first cinematographer, Georgy Rerberg, had deteriorated. After seeing the poorly developed material, Tarkovsky fired Rerberg. By the time the film stock defect was discovered, Tarkovsky had shot all the outdoor scenes and had to abandon them. Safiullin contends that Tarkovsky was so despondent that he wanted to abandon further work on the film.[11]

After the loss of the film stock, the Soviet film boards wanted to shut the film down, but Tarkovsky came up with a solution: he asked to be allowed to make a two-part film, which meant additional deadlines and more funds. Tarkovsky ended up reshooting almost all of the film with a new cinematographer, Alexander Knyazhinsky. According to Safiullin, the finished version of Stalker is completely different from the one Tarkovsky originally shot.[11]

The documentary film Rerberg and Tarkovsky: The Reverse Side of "Stalker" by Igor Mayboroda offers a different interpretation of the relationship between Rerberg and Tarkovsky. Rerberg felt that Tarkovsky was not ready for this script. He told Tarkovsky to rewrite the script in order to achieve a good result. Tarkovsky ignored him and continued shooting. After several arguments, Tarkovsky sent Rerberg home. Ultimately, Tarkovsky shot Stalker three times, consuming over 5,000 metres (16,000 ft) of film. People who have seen both the first version shot by Rerberg (as Director of Photography) and the final theatrical release say that they are almost identical. Tarkovsky sent home other crew members in addition to Rerberg, excluding them from the credits, as well.[citation needed]

The central part of the film, in which the characters travel within the Zone, was shot in a few days at two deserted hydro power plants on the Jägala river near Tallinn, Estonia.[12] The shot before they enter the Zone is an old Flora chemical factory in the center of Tallinn, next to the old Rotermann salt storage (now Museum of Estonian Architecture), and the former Tallinn Power Plant, now Tallinn Creative Hub, where a memorial plate of the film was set up in 2008. Some shots within the Zone were filmed in Maardu, next to the Iru Power Plant, while the shot with the gates to the Zone was filmed in Lasnamäe, next to Punane Street behind the Idakeskus. Other shots were filmed near the Tallinn–Narva highway bridge on the Pirita river.[12]

Several people involved in the film production, including Tarkovsky, died from causes that some crew members attributed to the film's long shooting schedule in toxic locations. Sound designer Vladimir Sharun recalled:

"We were shooting near Tallinn in the area around the small river Jägala with a half-functioning hydroelectric station. Up the river was a chemical plant and it poured out poisonous liquids downstream. There is even this shot in Stalker: snow falling in the summer and white foam floating down the river. In fact it was some horrible poison. Many women in our crew got allergic reactions on their faces. Tarkovsky died from cancer of the right bronchial tube. And Tolya Solonitsyn too. That it was all connected to the location shooting for Stalker became clear to me when Larisa Tarkovskaya died from the same illness in Paris."[13]

Style

Like Tarkovsky's other films, Stalker relies on long takes with slow, subtle camera movement, rejecting the use of rapid montage. The film contains 142 shots in 163 minutes, with an average shot length of more than one minute and many shots lasting for more than four minutes.[14] Almost all of the scenes not set in the Zone are in sepia or a similar high-contrast brown monochrome.

Soundtrack

The Stalker film score was composed by Eduard Artemyev, who had also composed the scores for Tarkovsky's previous films Solaris and Mirror. For Stalker, Artemyev composed and recorded two different versions of the score. The first score was done with an orchestra alone but was rejected by Tarkovsky. The second score that was used in the final film was created on a synthesizer along with traditional instruments that were manipulated using sound effects.[15]

In the final film score, the boundaries between music and sound were blurred, as natural sounds and music interact to the point where they are indistinguishable. In fact, many of the natural sounds were not production sounds but were created by Artemyev on his synthesizer.[16]

For Tarkovsky, music was more than just a parallel illustration of the visual image. He believed that music distorts and changes the emotional tone of a visual image while not changing the meaning. He also believed that in a film with complete theoretical consistency music will have no place and that instead music is replaced by sounds. According to Tarkovsky, he aimed at this consistency and moved into this direction in Stalker and Nostalghia.[17]

In addition to the original monophonic soundtrack, the Russian Cinema Council (Ruscico) created an alternative 5.1 surround sound track for the 2001 DVD release.[11] In addition to remixing the mono soundtrack, music and sound effects were removed and added in several scenes. Music was added to the scene where the three are traveling to the Zone on a motorized draisine. In the opening and the final scene Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was removed and in the opening scene in Stalker's house ambient sounds were added, changing the original soundtrack, in which this scene was completely silent except for the sound of a train.[18]

Film score

Initially, Tarkovsky had no clear understanding of the musical atmosphere of the final film and only an approximate idea where in the film the music was to be. Even after he had shot all the material he continued his search for the ideal film score, wanting a combination of Oriental and Western music. In a conversation with Artemyev he explained that he needed music that reflects the idea that although the East and the West can coexist, they are not able to understand each other.[19] One of Tarkovsky's ideas was to perform Western music on Oriental instruments, or vice versa, performing Oriental music on European instruments. Artemyev proposed to try this idea with the motet Pulcherrima Rosa by an anonymous 14th century Italian composer dedicated to the Virgin Mary.[20]

In its original form Tarkovsky did not perceive the motet as suitable for the film and asked Artemyev to give it an Oriental sound. Later, Tarkovsky proposed to invite musicians from Armenia and Azerbaijan and to let them improvise on the melody of the motet. A musician was invited from Azerbaijan who played the main melody on a tar based on mugham, accompanied by orchestral background music written by Artemyev.[21] Tarkovsky, who, unusually for him, attended the full recording session, rejected the final result as not what he was looking for.[19]

Rethinking their approach, they finally found the solution in a theme that would create a state of inner calmness and inner satisfaction, or as Tarkovsky said "space frozen in a dynamic equilibrium". Artemyev knew about a musical piece from Indian classical music where a prolonged and unchanged background tone is performed on a tanpura. As this gave Artemyev the impression of frozen space, he used this inspiration and created a background tone on his synthesizer similar to the background tone performed on the tanpura. The tar then improvised on the background sound, together with a flute as a European, Western instrument.[22] To mask the obvious combination of European and Oriental instruments he passed the foreground music through the effect channels of his SYNTHI 100 synthesizer. These effects included modulating the sound of the flute and lowering the speed of the tar, so that what Artemyev called "the life of one string" could be heard. Tarkovsky was amazed by the result, especially liking the sound of the tar, and used the theme without any alterations in the film.[19]

Sound design

The title sequence is accompanied by Artemyev's main theme. The opening sequence of the film showing Stalker's room is mostly silent. Periodically one hears what could be a train. The sound becomes louder and clearer over time until the sound and the vibrations of objects in the room give a sense of a train's passing by without the train's being visible. This aural impression is quickly subverted by the muffled sound of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. The source of this music is unclear, thus setting the tone for the blurring of reality in the film.[23] For this part of the film Tarkovsky was also considering music by Richard Wagner or the Marseillaise.[citation needed]

In an interview with Tonino Guerra in 1979, Tarkovsky said that he wanted:

"...music that is more or less popular, that expresses the movement of the masses, the theme of humanity's social destiny...But this music must be barely heard beneath the noise, in a way that the spectator is not aware of it."[7]

In one scene, the sound of a train becomes more and more distant as the sounds of a house, such as the creaking floor, water running through pipes, and the humming of a heater become more prominent in a way that psychologically shifts the audience. While the Stalker leaves his house and wanders around an industrial landscape, the audience hears industrial sounds such as train whistles, ship foghorns, and train wheels. When the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor set off from the bar in an off-road vehicle, the engine noise merges into an electronic tone. The natural sound of the engine falls off as the vehicle reaches the horizon. Initially almost inaudible, the electronic tone emerges and replaces the engine sound as if time has frozen.[23]

I would like most of the noise and sound to be composed by a composer. In the film, for example, the three people undertake a long journey in a railway car. I'd like that the noise of the wheels on the rails not be the natural sound but elaborated upon by the composer with electronic music. At the same time, one mustn't be aware of music, nor natural sounds.

The journey to the Zone on a motorized draisine features a disconnection between the visual image and the sound. The presence of the draisine is registered only through the clanking sound of the wheels on the tracks. Neither the draisine nor the scenery passing by is shown, since the camera is focused on the faces of the characters. This disconnection draws the audience into the inner world of the characters and transforms the physical journey into an inner journey. This effect on the audience is reinforced by Artemyev's synthesizer effects, which make the clanking wheels sound less and less natural as the journey progresses. When the three arrive in the Zone initially, it appears to be silent. Only after some time, and only slightly audibly can one hear the sound of a distant river, the sound of the blowing wind, or the occasional cry of an animal. These sounds grow richer and more audible while the Stalker makes his first venture into the Zone, initially leaving the Professor and the Writer behind, and as if the sound draws him towards the Zone. The sparseness of sounds in the Zone draws attention to specific sounds, which, as in other scenes, are largely disconnected from the visual image. Animals can be heard in the distance but are never shown. A breeze can be heard, but no visual reference is shown. This effect is reinforced by occasional synthesizer effects which meld with the natural sounds and blur the boundaries between artificial and alien sounds and the sounds of nature.[23]

After the three travelers appear from the tunnel, the sound of dripping water can be heard. While the camera slowly pans to the right, a waterfall appears. While the visual transition of the panning shot is slow, the aural transition is sudden. As soon as the waterfall appears, the sound of the dripping water falls off while the thundering sound of the waterfall emerges, almost as if time has jumped. In the next scene Tarkovsky again uses the technique of disconnecting sound and visual image. While the camera pans over the burning ashes of a fire and over some water, the audience hears the conversation of the Stalker and the Writer who are back in the tunnel looking for the Professor. Finding the Professor outside, the three are surprised to realize that they have ended up at an earlier point in time. This and the previous disconnection of sound and the visual image illustrate the Zone's power to alter time and space. This technique is even more evident in the next scene where the three travelers are resting. The sounds of a river, the wind, dripping water, and fire can be heard in a discontinuous way that is now partially disconnected from the visual image. When the Professor, for example, extinguishes the fire by throwing his coffee on it, all sounds but that of the dripping water fall off. Similarly, we can hear and see the Stalker and the river. Then the camera cuts back to the Professor while the audience can still hear the river for a few more seconds. This impressionist use of sound prepares the audience for the dream sequences accompanied by a variation of the Stalker theme that has been already heard during the title sequence.[23]

During the journey in the Zone, the sound of water becomes more and more prominent, which, combined with the visual image, presents the Zone as a drenched world. In an interview Tarkovsky dismissed the idea that water has a symbolic meaning in his films, saying that there was so much rain in his films because it is always raining in Russia.[23] In another interview, on the film Nostalghia, however, he said "Water is a mysterious element, a single molecule of which is very photogenic. It can convey movement and a sense of change and flux."[24] Emerging from the tunnel called the meat grinder by the Stalker they arrive at the entrance of their destination, the room. Here, as in the rest of the film, sound is constantly changing and not necessarily connected to the visual image. The journey in the Zone ends with the three sitting in the room, silent, with no audible sound. When the sound resumes, it is again the sound of water but with a different timbre, softer and gentler, as if to give a sense of catharsis and hope. The transition back to the world outside the Zone is supported by sound. While the camera still shows a pool of water inside the Zone, the audience begins to hear the sound of a train and Ravel's Boléro, reminiscent of the opening scene. The soundscape of the world outside the Zone is the same as before, characterized by train wheels, foghorns of a ship and train whistles. The film ends as it began, with the sound of a train passing by, accompanied by the muffled sound of Beethoven's Ninth symphony, this time the Ode to Joy from the final moments of the symphony. As in the rest of the film the disconnect between the visual image and the sound leaves the audience unclear whether the sound is real or an illusion.[23]

Reception

Critical response

Upon its release the film's reception was less than favorable. Officials at Goskino, a government group otherwise known as the State Committee for Cinematography, were critical of the film.[25] On being told that Stalker should be faster and more dynamic, Tarkovsky replied:

The film needs to be slower and duller at the start so that the viewers who walked into the wrong theatre have time to leave before the main action starts.

The Goskino representative then stated that he was trying to give the point of view of the audience. Tarkovsky supposedly retorted:

I am only interested in the views of two people: one is called Bresson and one called Bergman.[26]

More recently, reviews of the film have been highly positive. It earned a place in the British Film Institute's "50 Greatest Films of All Time" poll conducted for Sight & Sound in September 2012. The group's critics listed Stalker at #29, tied with the 1985 film Shoah.[27] Critic Derek Adams of the Time Out Film Guide has compared Stalker to Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now, also released in 1979, and argued that "as a journey to the heart of darkness" Stalker looks "a good deal more persuasive than Coppola's."[28] Slant Magazine reviewer Nick Schager has praised the film as an "endlessly pliable allegory about human consciousness". In Schager's view, Stalker shows "something akin to the essence of what man is made of: a tangled knot of memories, fears, fantasies, nightmares, paradoxical impulses, and a yearning for something that's simultaneously beyond our reach and yet intrinsic to every one of us."[5]

In 2018, the film was voted the 49th greatest foreign-language film of all time in a poll of 209 critics in 43 countries.[29]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film is rated at 100% based on 41 reviews with an average rating of 8.57/10. Its critical consensus states, "Stalker is a complex, oblique parable that draws unforgettable images and philosophical musings from its sci-fi/thriller setting."[30]

Box office

Stalker sold 4.3 million tickets in the Soviet Union.[4]

Awards

The film was awarded the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the Cannes Film Festival, and the Audience Jury Award – Special Mention at Fantasporto, Portugal.[citation needed]

Home media

- In East Germany, DEFA did a complete German dubbed version of the movie which was shown in cinema in 1982. This was used by Icestorm Entertainment on a DVD release, but was heavily criticized for its lack of the original language version, subtitles and had an overall bad image quality.[citation needed]

- RUSCICO produced a version for the international market containing the film on two DVDs with remastered audio and video. It contains the original Russian audio in an enhanced Dolby Digital 5.1 remix as well as the original mono version. The DVD also contains subtitles in 13 languages and interviews with cameraman Alexander Knyazhinsky, painter and production designer Rashit Safiullin and composer Eduard Artemyev.[11]

- Criterion Collection released a remastered edition DVD and Blu-Ray on 17 July 2017. Included in the special features is an interview with film critic Geoff Dyer, author of the book Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room. [31]

Influence and legacy

- In the song Dissidents from the 1984 album The Flat Earth by Thomas Dolby, the bridge between two verses includes a narrative from the film.[citation needed]

- The track entitled The Avenue by British Group Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark samples the sound of a train in motion, recorded directly from the film. Band member and songwriter Andy McCluskey refers to the film as, “One of the most haunting pieces of film and music that I ever saw". The track features as a B-side on the group's 1984 hit single Locomotion.[32]

- The Chernobyl disaster, which occurred seven years after the film was made, led to depopulation in the surrounding area—officially called the "Exclusion Zone"—much like the "Zone" of the film. Some of the people employed to take care of the abandoned nuclear power plant refer to themselves as "stalkers".[33]

- Stalker was the inspiration for the 1995 album of the same title by Robert Rich and B. Lustmord,[34] which has been noted for its eerie soundscapes and dark ambience.[35]

- Ambient music duo Stars of the Lid sampled the ending of Stalker in their song "Requiem for Dying Mothers, Part 2", released on their 2001 album The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid.

- The Prodigy's music video "Breathe" is heavily influenced by film's visuals and cinematography.[citation needed]

- In 2007, the Ukrainian video-game developer GSC Game World published S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, an open-world, first-person shooter loosely based on both the film and the original novel.[citation needed]

- In 2012, the English writer Geoff Dyer published Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room drawing together his personal observations as well as critical insights about the film and the experience of watching it.[citation needed]

- The 2012 film Chernobyl Diaries also involves a tour guide, similar to a stalker, giving groups "extreme tours" of the Chernobyl area.[citation needed]

- The lyrics of the 2013 album Pelagial by the progressive metal band The Ocean are inspired by the film.[36]

- Jonathan Nolan, co-creator of Westworld, cites Stalker as an influence on his work for the HBO series.[37]

- In the 2017 film Atomic Blonde, the protagonist Lorraine Broughton goes into an East Berlin theater showing Stalker.[38]

- Metro Exodus video game includes location reconstructed from the movie. The whole Metro video game series is partly influenced by the novel Roadside Picnic on which the film was based.[citation needed]

- Annihilation (2018), a science fiction psychological horror film written and directed by Alex Garland, although based on the eponymous novel by Jeff VanderMeer, for some critics seems to have obvious similarities with the Roadside Picnic and Stalker.[39][40][41][42] While Nerdist Industries' Kyle Anderson notes even stronger resemblance with the 1927 short story "The Colour Out of Space" by H. P. Lovecraft[43] (also adapted for the screen as Color Out of Space in 2019), about a meteorite that lands in a swamp and unleashes a mutagenic plague.[44]

- Chris McCoy of the Memphis Flyer found the film (Annihilation) reminiscent both of "The Colour Out of Space", as well as the novel (Roadside Picnic) and its film adaptation (Stalker).[44] However, such notions prompted the author of the Annihilation novel, upon which the movie is based, to state that his story "is 100% NOT a tribute to Picnic/Stalker" via his official Twitter account.[45]

Notes

- ^ In the Soviet Union the role of a producer was different from that in Western countries and more similar to the role of a line producer or a unit production manager.[1]

References

- ^ Johnson, Vida T.; Graham Petrie (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, pp. 57–58, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

- ^ a b Johnson, Vida T.; Graham Petrie (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, pp. 139–140, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

- ^ "STALKER (A)". British Board of Film Classification. 2 December 1980. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ a b Segida, Miroslava; Sergei Zemlianukhin (1996), Domashniaia sinemateka: Otechestvennoe kino 1918–1996 (in Russian), Dubl-D

- ^ a b c Nick Schager (25 April 2006). "Stalker". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Tarkovsky, Andrei (1991). Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986 (PDF). Seagull Books. p. 136. ISBN 81-7046-083-2. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Gianvito, John (2006), Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews, University Press of Mississippi, pp. 50–54, ISBN 1-57806-220-9

- ^ a b c Dyer, Geoff (5 February 2009). "Danger! High-radiation arthouse!". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ Semley, John (29 July 2017). "Why Andrei Tarkovsky's interminably dull 1979 sci-fi masterpiece "Stalker" is the movie we need right now". Salon. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ Tarkovsky, Andrey [sic] (1987) [1986]. Sculpting in Time. Reflections on the Cinema. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 193. ISBN 0292776241.

{{cite book}}: External link in|orig-year= - ^ a b c d e R·U·S·C·I·C·O-DVD of Stalker Archived 15 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Norton, James, Stalking the Stalker, Nostalghia.com, retrieved 15 September 2010

- ^ Tyrkin, Stas (23 March 2001), In Stalker Tarkovsky foretold Chernobyl, Nostalghia.com, retrieved 25 May 2009

- ^ Johnson, Vida T.; Graham Petrie (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, p. 152, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

- ^ Johnson, Vida T.; Graham Petrie (1994), The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Indiana University Press, p. 57, ISBN 0-253-20887-4

- ^ Varaldiev, Anneliese, Russian Composer Edward Artemiev, Electroshock Records, retrieved 12 June 2009

- ^ Tarkovsky, Andrei (1987), Sculpting in Time, translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair, University of Texas Press, pp. 158–159, ISBN 0-292-77624-1

- ^ Bielawski, Jan; Trond S. Trondsen (2001–2002), The RusCiCo Stalker DVD, Nostalghia.com, retrieved 14 June 2009

- ^ a b c Egorova, Tatyana, Edward Artemiev: He has been and will always remain a creator…, Electroshock Records, retrieved 7 June 2009, (originally published in Muzikalnaya zhizn, Vol. 17, 1988)

- ^ Egorova, Tatyana (1997), Soviet Film Music, Routledge, pp. 249–252, ISBN 3-7186-5911-5, retrieved 7 June 2009

- ^ "August 26 – International Day of Azerbaijani Mugham". www.today.az. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Turovskaya, Maya (1991), 7½, ili filmy Andreya Tarkovskovo (in Russian), Moscow: Iskusstvo, ISBN 5-210-00279-9, retrieved 7 June 2009

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Stefan (November 2007), "The edge of perception: sound in Tarkovsky's Stalker", The Soundtrack, 1 (1), Intellect Publishing: 41–52, doi:10.1386/st.1.1.41_1

- ^ Mitchell, Tony (Winter 1982–1983), "Tarkovsky in Italy", Sight and Sound, The British Film Institut e: 54–56, retrieved 13 June 2009

- ^ Tsymbal E., 2008. Tarkovsky, Sculpting the Stalker: Towards a new language of cinema, London, black dog publishing

- ^ Dyer, Geoff (1987). Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-85786-167-2.

- ^ Christie, Ian (29 July 2015) [2012]. "The 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound. Contributors to Sight & Sound magazine. Retrieved 19 December 2015 – via British Film Institute.

- ^ Adams, Derek (2006). Stalker, Time Out Film Guide

- ^ "The 100 greatest foreign-language films". BBC Culture. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Stalker (1979)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ "Stalker (1979) The Criterion Collection". Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Club 66 : The Avenue". omd-messages.co.uk. 1 February 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Johncoulhart.com article". Johncoulthart.com. 7 December 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "Robert Rich & B. Lustmord - Stalker". sputnikmusic.com. 4 December 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ "Robert Rich / B.Lustmord — Stalker". Exposé. 1 August 1996. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Mustein, Dave (8 April 2013). "The Ocean Collective Explore Every Imaginable Zone With Pelagial". MetalSucks. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ "Facebook Live discussing Westworld moderated by The Atlantic's Christopher Orr". 9 October 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "Atomic Blonde". Films in films. 3 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ Ignatiy Vishnevetsky (24 February 2018). "What Annihilation learned from Andrei Tarkovsky's Soviet sci-fi classics". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Alex Lindstrom (11 June 2018). "Fear and Loathing in the Zone: Annihilation's Dreamy 'Death Drive'". PopMatters. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Stuart Starosta (2 December 2015). "Roadside Picnic: Russian SF classic with parallels to Vandermeer's Area X | Fantasy Literature: Fantasy and Science Fiction Book and Audiobook Reviews". fantasyliterature.com. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Christopher Campbell (24 February 2018). "Watch 'Annihilation' and 'Mute,' Then Watch These Movies". Film School Rejects. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (21 February 2018). "Annihilation is a Scary, Cosmic Trip (Review)". Nerdist. Nerdist Industries. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b McCoy, Chris (2 March 2018). "Annihilation". Memphis Flyer. Contemporary Media. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ VanderMeer, Jeff (17 July 2016). "Annihilation is 100% NOT a tribute to Picnic/Stalker. But I keep hearing Tanis = Annihilation. Why?". @jeffvandermeer. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

External links

- Stalker at IMDb

- Stalker at AllMovie

- Stalker at Rotten Tomatoes

- Stalker, released on official Mosfilm YouTube channel, with subtitles in multiple languages

- Stalker at Nostalghia.com, a website dedicated to Tarkovsky, featuring interviews with members of the production team

- Geopeitus.ee – filming locations of Stalker (in Estonian)

- A unique perspective on the making of Stalker: The testimony of a mechanic toiling away under Tarkovsky's guidance – article on the production of Stalker

- Stalker: Meaning and Making an essay by Mark Le Fanu at the Criterion Collection

- 1979 films

- 1970s avant-garde and experimental films

- 1970s science fiction drama films

- Existentialist works

- Films about religion

- Films based on Russian novels

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Films based on works by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky

- Films directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

- Films scored by Eduard Artemyev

- Films shot in Estonia

- Films shot in Moscow

- Films shot in Tajikistan

- Films partially in color

- Metaphysical fiction films

- Mosfilm films

- Rail transport films

- Russian-language films

- Russian science fiction drama films

- Soviet avant-garde and experimental films

- Soviet films

- Soviet science fiction drama films

- 1979 drama films