Watermelon stereotype

The watermelon stereotype is a stereotype of African Americans that states that African Americans have an unusually great appetite for watermelons. This stereotype has remained prevalent into the 21st century.[1]

Watermelons have been viewed as a major society in the iconography of racism in the United States.[2]

The truthfulness of the stereotype has been questioned; one survey conducted from 1994 to 1996 showed that African Americans, at the time 12.5 percent of the country's population, only accounted for 11.1 percent of the United States' watermelon consumption.[3][citation needed]

History

The stereotype that African Americans are excessively fond of watermelon emerged for a specific historical reason and served a specific political purpose. ... This racist trope then exploded in American popular culture, becoming so pervasive that its historical origin became obscure. ... Whites used the stereotype to denigrate black people—to take something they were using to further their own freedom, and make it an object of ridicule.

—William Black, The Atlantic, December 8, 2014.[4]

The first published caricature of blacks reveling in watermelon is believed to have appeared in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in 1869.[4] Defenders of slavery used the fruit to paint African Americans as a simple-minded people who were happy when provided with watermelon and a little rest.[5] The slaves' enjoyment of watermelon was also seen by the Southern whites as a sign of their own supposed benevolence.[4] The stereotype was perpetuated in minstrel shows often depicting African Americans as ignorant and lazy, given to song and dance and inordinately fond of watermelon.[6]

For several decades in the late nineteenth century through to the mid-twentieth century, the stereotype was promoted through caricatures in print, film, sculpture and music, and was a common decorative theme on household goods.[7] Even as recently as Barack Obama's 2008 presidential campaign and his subsequent administrations, watermelon imagery has been used by his detractors.[8]

In popular culture

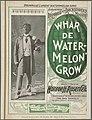

The link between African-Americans and watermelons may have been promoted in part by African-American minstrels who sang popular songs such as "The Watermelon Song" and "Oh, Dat Watermelon" in their shows, and which were set down in print in the 1870s. The 1893 World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago planned to include a "Colored People's Day" featuring African American entertainers and free watermelons for the African-American visitors whom the exposition's organizers hoped to attract. It was a flop, as the city's African-American community boycotted the exposition, along with many of the performers booked to attend on Colored People's Day.[7]

At the end of the 19th century, there was a brief genre of "watermelon pictures" – cinematic caricatures of African-American life showing such supposedly typical pursuits as eating watermelons, cakewalking and stealing chickens, with titles such as The Watermelon Contest (1896), Dancing Darkies (1896), Watermelon Feast (1896), and Who Said Watermelon? (1900, 1902).[9] The African-American characters in such features were initially played by Black performers, but from about 1903 onwards, they were replaced by white actors performing in blackface.[9]

Several of the films depicted African-Americans as having a virtually uncontrollable appetite for watermelons; for instance, The Watermelon Contest and Watermelon Feast include scenes of African-American men consuming the fruits at such a speed that they spew out mush and seeds. The author Novotny Lawrence suggests that such scenes had a subtext of representing Black male sexuality, in which Black men "love and desire the fruit in the same manner that they love sex … In short, black males have a watermelon 'appetite' and are always trying to see 'who can eat the most' with the strength of this 'appetite' depicted by black males uncontrollably devouring watermelon."[10]

Early-1900s postcards often depicted African-Americans as animalistic creatures "happy to do nothing but eat watermelon" – a bid to dehumanize them.[8] Other such "Coon cards", as they were popularly known, depicted African-Americans stealing, fighting over, and becoming watermelons.[11] One poem from the early 1900s (pictured right) reads:[12]

George Washington Watermelon Columbus Brown

I'se black as any little coon in town

At eating melon I can put a pig to shame

For Watermelon am my middle name

In March 1916, Harry C. Browne recorded a song titled "Nigger Love a Watermelon Ha!, Ha! Ha!", set to the tune of the popular folk song "Turkey in the Straw".[13][14] Such songs were popular during that period and many made use of the watermelon stereotype.[8] The script for Gone with the Wind (1939) contained a scene in which Scarlett O'Hara's slave Prissy, played by Butterfly McQueen, eats watermelon, which the actress refused to perform.[7] Use of this stereotype started to die down around the 1950s, and had mostly vanished by 1970, although its continued power as a stereotype could still be recognized in films such as Watermelon Man (1970), The Watermelon Woman (1996), and Bamboozled (2001).[8] Watermelons also provided a theme for many racial jokes in the 2000s.[11]

Protesters against African-Americans frequently, among other things, hold up watermelons;[2] racist imagery of President Barack Obama consuming watermelon was subject of viral emails circulated by his political opponents. After his election, watermelon-themed imagery of Obama continued to be created and endorsed.[8]

In February 2009, Los Alamitos Mayor Dean Grose tendered his resignation (albeit temporarily) after forwarding the White House an email deemed as racist. The message displayed a picture of the White House lawn planted with watermelons.[15] Grose claimed that he was not aware of the watermelon stereotype.[16] A statue of Obama holding a watermelon in Kentucky drew criticism; the owner of the statue maintained that the watermelon was there because "[the statue] might get hungry standing out here."[17]

On October 1, 2014, the Boston Herald ran an editorial cartoon by Jerry Holbert depicting an intruder asking if Obama has tried watermelon-flavored toothpaste, to much controversy.[18]

At the National Book Awards ceremony in November 2014, author Daniel Handler made a controversial remark after author Jacqueline Woodson was presented with an award for young people's literature. Woodson, who is Black, won the award for Brown Girl Dreaming. During the ceremony, Handler noted that Woodson is allergic to watermelon, a reference to the racist stereotype. His comments were immediately criticized;[19][20] Handler apologized via Twitter and donated $10,000 to We Need Diverse Books, and promised to match donations up to $100,000.[21] In a New York Times op-ed published shortly thereafter, "The Pain of the Watermelon Joke", Jacqueline Woodson explained that "in making light of that deep and troubled history" with his joke, Daniel Handler had come from a place of ignorance, but underscored the need for her mission to "give people a sense of this country's brilliant and brutal history, so no one ever thinks they can walk onto a stage one evening and laugh at another's too often painful past".[22][23][24]

On January 7, 2016, Australian cartoonist Chris Roy Taylor published a cartoon of Jamaican cricketer Chris Gayle with a whole watermelon in his mouth.[25] Gayle had been in the news for making controversial suggestive comments towards a female interviewer during a live broadcast.[26] The cartoon depicted a Cricket Australia official asking a boy if he could "borrow" the watermelon, so Gayle would be unable to speak.[25] A couple of days earlier, a video of a boy eating a whole watermelon – rind and all – in the stands of a cricket match had gone viral.[27] Taylor said he was unaware of the stereotype, and the cartoon was removed.[28]

In "Safety Training", an episode of the American television series The Office, Michael Scott (Steve Carell) throws a watermelon off the roof of the office onto a trampoline. After it bounces and hits a car, Michael fears that the car belongs to Stanley Hudson (Leslie David Baker), who is African-American, and that Stanley will think he is racist; Michael tells Dwight Schrute (Rainn Wilson), "Deactivate the car alarm, clean up the mess, find out whose car that is. If it's Stanley's, call the offices of James P. Albini. See if he handles hate crimes."

On October 22, 2017, the Fox & Friends morning show on the Fox News Channel dressed a Hispanic boy, who was mistaken by many in the mainstream media as an African-American, in a watermelon Halloween costume, drawing ire on social media: "Overt racism, foolish racism, or tone deaf racism? Take your pick, it's still racism."[29]

In 2019, the video game Crash Team Racing: Nitro Fueled featured an alternative skin for the character of Tawna, named "Watermelon Tawna". The skin has darker fur and darker hair and wears a watermelon-themed T-shirt. Shortly after the skin was introduced, and after some social media discussion of the issue, a patch was issued that renamed the skin "Summertime Tawna".[30]

Gallery

-

Lithograph of a black boy holding a watermelon, circa 1850–1900

-

Lithograph of black people dancing around a pile of watermelons, circa 1900

-

Postcard ("Coon card") from the 1900s

-

"Coon card" from 1904

-

"Coon card" from 1910

-

"Coon card" from 1911, with the title "You can plainly see how miserable I am"

-

"Whar De Watermelon Grow", sheet music of an 1898 minstrel song

-

"The Coon's Trade-mark: A Watermelon, Razor, Chicken and Coon", sheet music of an 1898 minstrel song. The razor was used for fighting, while fried chicken is also used in stereotypes of African-Americans.

-

Reproduction of an old tin sign advertising Picaninny Freeze, a frozen treat.

-

A character from the 1941 cartoon Scrub Me Mama with a Boogie Beat enjoying a watermelon.

-

I Know'd It Was Ripe, c. 1888 by Thomas Hovenden Brooklyn Museum

-

Valentine's Day card, c. 1940

See also

Further reading

- Pilgrim, David. Watermelons, Nooses, and Straight Razors: Stories from the Jim Crow Museum. PM Press. Oct 9, 2017.

- How Watermelon's Reputation Got Tangled In Racism. University of Maryland. Aug 2, 2019

- Greenlee, Cynthia. On eating watermelon in front of white people: “I’m not as free as I thought”. VOX. Aug 29, 2019.

- Black, William R. How Watermelons Became Black. Journal of the Civil War Era Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 64-86 (23 pages). University of North Carolina Press. March 2018.

- Sousa, Emily and Manish Raizada. Contributions of African Crops to American Culture and Beyond: The Slave Trade and Other Journeys of Resilient Peoples and Crops. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. July 23, 2020.

- Maynard, David and Donald. The Cambridge World History of Food - Cucumbers, Melons, and Watermelons. Cambridge University Press. 2000.[31]

References

- ^ Sheet, Connor Adams (August 3, 2012). "National Watermelon Day Brings Racists Out Despite Lack Of Facts To Back Up Stereotype". International Business Times. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ a b "II.C.6. – Cucumbers, Melons, and Watermelons". The Cambridge World History of Food. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ Lucier, G.; Lin, Biing-Hwan (November 2001). "Factors Affecting Watermelon Consumption in the United States" (PDF). Vegetables and Specialties: Situation and Outlook: 23–29. VGS-287. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Black, William (December 8, 2014). "How Watermelons Became a Racist Trope". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Wade, Lisa (December 26, 2012). "Watermelon: Symbolizing the Supposed Simplicity of Slaves". The Society Pages. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Fences. Shmoop Literature Guide. Los Altos: Shmoop. 2010. p. 26. ISBN 9781610624190.

- ^ a b c Smith, Andrew F. (2007). The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195307962.

- ^ a b c d e "The Coon Obsession with Chicken & Watermelon". History on the Net. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Massood, Paula J. (2008). "Urban Cinema". In Boyd, Todd (ed.). African Americans and Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 90. ISBN 9780313064081.

- ^ Novotny Lawrence (2008). Blaxploitation Films of the 1970s. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-96097-7.

- ^ a b "Blacks and Watermelons". Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. Ferris State University. May 2008. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ "WHO SAID WATERMELON?". History on the Net. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ "Nigger Love a Watermelon Ha! Ha! Ha!". History on the Net. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Theodore R., III (May 11, 2014). "Recall That Ice Cream Truck Song? We Have Unpleasant News For You". NPR. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitchell, Mary (February 26, 2009). "Monkeys, watermelons and black people". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Mayor Who Sent Obama Watermelon Email Quits". Huffington Post. February 27, 2009. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Wing, Nick (December 27, 2012). "Danny Hafley, Kentucky Man, Defends Watermelon-Eating Obama Display: He 'Might Get Hungry'". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Killough, Ashley (October 1, 2014). "Boston Herald apologizes for Obama cartoon after backlash". CNN. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ^ Gambino, Lauren (November 20, 2014). "Lemony Snicket apologizes for watermelon joke about black writer at National Book Awards". The Guardian. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Anne (November 20, 2014). "Lemony Snicket's Series of Unfortunate Racist Jokes". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (November 21, 2014). "Daniel Handler does more than apologize for his 'watermelon' joke". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ Woodson, Jacqueline (November 28, 2014). "The Pain of the Watermelon Joke". The New York Times. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ Frizell, Sam (November 29, 2014). "Jacqueline Woodson Responds to Racist Watermelon Joke". Time. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Award-Winning Author Jacqueline Woodson Responds To Racist Joke". The Huffington Post. Associated Press. November 29, 2014. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Taylor, Chris 'ROY' (January 6, 2016). "Cartoon". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ Eastaugh, Sophie (January 6, 2016). "Chris Gayle: Cricketer fined after telling female reporter, 'Don't blush, baby'". CNN. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Donnelly, Ashley (January 4, 2016). "'Watermelon boy' finds fame with Australia cricket fans". BBC News. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Chris 'ROY' (January 6, 2016). "Thanx @J_CharlesBM yes Living in Australia I had no idea this stereotype even existed As such I have deleted cartoon". Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Fox & Friends draws ire by dressing up black child as watermelon slice for Halloween". AOL.com. October 22, 2017.

- ^ Taormina, Anthony (July 14, 2019). "Crash Team Racing Renames Racially Offensive Skins". Game Rant. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Maynard, David; Maynard, Donald (2000), Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (eds.), "Cucumbers, Melons, and Watermelons", The Cambridge World History of Food, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 298–313, ISBN 978-1-139-05863-6, retrieved January 23, 2021

External links

Media related to Watermelon stereotype at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Watermelon stereotype at Wikimedia Commons