SS Great Eastern

Great Eastern at Heart's Content after laying the first transatlantic cable, July 1866

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Great Eastern |

| Port of registry | Liverpool |

| Ordered | 1853 |

| Builder | J. Scott Russell & Co., Millwall |

| Laid down | 1 May 1854 |

| Launched | 31 January 1858 |

| Completed | 1859 |

| Maiden voyage | 30 August 1859 |

| In service | 1859 |

| Out of service | 1889 |

| Stricken | 1889 |

| Homeport | Liverpool |

| Nickname(s) | The great ship, Leviathan (Original name), Great Babe (As Brunel called her) |

| Fate | Scrapped 1889–90 |

| Status | Scrapped |

| Notes | Struck rocks on 27 August 1862 Was the largest ship for four decades |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Passenger ship |

| Tonnage | 18,915 GRT[1] |

| Displacement | 32,160 tons |

| Length | 692 ft (211 m) |

| Beam | 82 ft (25 m) |

| Decks | 4 decks |

| Propulsion | Four steam engines for the paddles and an additional engine for the propeller. Total power was estimated at 8,000 hp (6,000 kW). Rectangular boilers[2] |

| Speed | 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph)[3] |

| Boats & landing craft carried | 18 lifeboats; after 1860 20 lifeboats |

| Capacity | 4,000 passengers |

| Complement | 418 |

SS Great Eastern was an iron sailing steamship designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and built by J. Scott Russell & Co. at Millwall Iron Works on the River Thames, London. She was by far the largest ship ever built at the time of her 1858 launch, and had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refuelling. Her length of 692 feet (211 m) was only surpassed in 1899 by the 705-foot (215 m) 17,274-gross-ton RMS Oceanic, her gross tonnage of 18,915 was only surpassed in 1901 by the 701-foot (214 m) 21,035-gross-ton RMS Celtic, and her 4,000-passenger capacity was surpassed in 1913 by the 4,935-passenger SS Imperator. The ship's five funnels were rare and were later reduced to four. The vessel also had the largest set of paddle wheels.

Brunel knew her affectionately as the "Great Babe". He died in 1859 shortly after her maiden voyage, during which she was damaged by an explosion. After repairs, she plied for several years as a passenger liner between Britain and North America before being converted to a cable-laying ship and laying the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866.[4] Finishing her life as a floating music hall and advertising hoarding (for the department store Lewis's) in Liverpool, she was broken up on Merseyside in 1889.

History

Concept

After his success in pioneering steam travel to North America with Great Western and Great Britain, Brunel turned his attention to longer voyages as far as Australia and realised the potential of a ship that could travel round the world without the need of refuelling.[5]

On 25 March 1852, Brunel made a sketch of a steamship in his diary and wrote beneath it: "Say 600 ft x 65 ft x 30 ft" (180 m x 20 m x 9.1 m). These measurements were six times larger by volume than any ship afloat; such a large vessel would benefit from economies of scale and would be both fast and economical, requiring fewer crew than the equivalent tonnage made up of smaller ships. Brunel realised that the ship would need more than one propulsion system; since twin screws were still very much experimental, he settled on a combination of a single screw and paddle wheels, with auxiliary sail power. Although Brunel had pioneered the screw propeller on a large scale with the Great Britain, he did not believe that it was possible to build a single propeller and shaft (or, for that matter, a paddleshaft) that could transmit the required horsepower to drive his giant ship at the required speed.[6]

Brunel showed his idea to John Scott Russell, an experienced naval architect and ship builder whom he had first met at the Great Exhibition. Scott Russell examined Brunel's plan and made his own calculations as to the ship's feasibility. He calculated that it would have a displacement of 20,000 tons and would require 8,500 horsepower (6,300 kW) to achieve 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph), but believed it was possible. At Scott Russell's suggestion, they approached the directors of the Eastern Steam Navigation Company.

1854–1859: Construction to maiden voyage

Construction

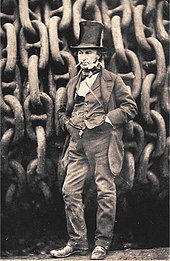

Brunel entered into a partnership with John Scott Russell, an experienced Naval Architect and ship builder, to build the Great Eastern. Unknown to Brunel, Russell was in financial difficulties. The two men disagreed on many details. It was Brunel's final great project, and he collapsed from a stroke after being photographed on her deck, and died only ten days later, a mere four days after Great Eastern's first sea trials. About the ship, Brunel said "I have never embarked on any one thing to which I have so entirely devoted myself, and to which I have devoted so much time, thought and labour, on the success of which I have staked so much reputation."

The Great Eastern was built by Messrs Scott Russell & Co. of Millwall, London, the keel being laid down on 1 May 1854. She was finally launched —after many technical difficulties— on 31 January 1858. She was 211 metres (692 ft 3 in) long, 25 metres (82 ft 0 in) wide, with a draught of 6.1 metres (20 ft 0 in) unloaded and 9.1 metres (29 ft 10 in) fully laden, and displaced 32,000 tons fully loaded. In comparison, SS Persia, launched in 1856, was 119 m (390 ft 5 in) long with a 14 m (45 ft 11 in) beam. She was at first named the Leviathan, but her high building and launching costs ruined the Eastern Steam Navigation Company and so she lay unfinished for a year before being sold to the Great Eastern Ship Company and finally renamed Great Eastern. It was decided she would be more profitable on the Southampton–New York run, and she was outfitted accordingly. Her eleven-day maiden voyage began on 17 June 1860, with 35 paying passengers, 8 company "dead heads" (passengers who do not pay) and 418 crew.

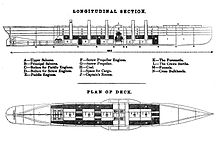

The hull was an all-iron construction, a double hull of 19-millimetre (0.75 in) wrought iron in 0.86 m (2 ft 10 in) plates with ribs every 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in). Internally the hull was divided by two 107 m (351 ft 1 in) long, 18 m (59 ft 1 in) high, longitudinal bulkheads and further transverse bulkheads dividing the ship into nineteen compartments. The Great Eastern was the first ship to incorporate the double-skinned hull, a feature which would not be seen again in a ship for 100 years, but which is now compulsory for reasons of safety. She had sail, paddle and screw propulsion. The paddle-wheels were 17 m (55 ft 9 in) in diameter and the four-bladed screw-propeller was 7.3 m (23 ft 11 in) across. The power came from four steam engines for the paddles and an additional engine for the propeller. Total power was estimated at 6,000 kilowatts (8,000 hp). She had six masts (said to be named after the days of a week - Monday being the fore mast and Saturday the spanker mast), providing space for 1,686 square metres (18,150 sq ft) of sails (7 gaff and maximum 9 (usually 4) square sails), rigged similar to a topsail schooner with a main gaff sail (fore-and-aft sail) on each mast, one "jib" on the fore mast and three square sails on masts no. 2 and no. 3 (Tuesday & Wednesday); for a time mast no. 4 was also fitted with 3 yards (2.7 m). In later years, some of the yards were removed. According to some sources she would have carried 5,435 m2 (58,500 sq ft). This amount of canvas is obviously too much for seven fore-and-aft sails and maximum 9 square sails. This (larger) figure of sail area lies only a few square meters below that the famous Flying P-Liner Preussen carried - with her five full-rigged masts of 30 square sails and a lot of stay sails. Setting sails turned out to be unusable at the same time as the paddles and screw were under steam, because the hot exhaust from the five (later four) funnels would set them on fire. Her maximum speed was 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).

Launch

Two people were killed in the difficult sideways-launch of the Great Eastern, and the ship became known to some as the unlucky ship. She was involved in a series of accidents, including an unfortunate incident in which an overheated steam pipe launched funnel no. 1 like a rocket, killing a crew member and five boiler men in the process. It was caused by a valve being left shut by accident after a pressure test of the system.[7] The maiden voyage from Southampton to New York began on 17 June 1860. Among the 35 passengers, eight officials and a crew of 418, were two journalists, Zerah Colburn and Alexander Lyman Holley.

Great Eastern Rock incident

On August 27 1862, the Great Eastern suffered an incident similar to that of the Titanic, but did not sink. She scraped on an uncharted rock needle (afterwards named the Great Eastern Rock) one mile (1.6 km) east of Montauk, New York on Long Island, opening a gash in the outer hull over 2.7 metres (9 ft) wide and 25 metres (83 ft) long, perhaps 60 times the area of the Titanic's damage. However, the Great Eastern's inner hull was unbroken, and she made her way into New York the next day under her own steam. Nobody was hurt, indeed the passengers never even knew what had happened. Because of this accident, some have claimed that the Titanic disaster was caused by diminishing safety standards of the late 19th century, as competing shipping lines sought to outdo each other in making faster and faster crossings of the Atlantic.[8]

In October 2007, the recovery of a 6,500-pound (2.9 t) anchor in 70 feet (21 m) of water about four miles (6.4 km) from the rock has stirred speculation that it may have belonged to the Great Eastern.[9]

Suez Canal concerns

The Suez Canal, which opened in 1869, was a setback for the ship: the ship was too wide for the canal, and going around Africa it would not be able to compete with ships that could use the canal.

Break up

At the end of her cable-laying career she was refitted once again as a liner but once again efforts to make her a commercial success failed. She was used as a showboat, a floating palace/concert hall and gymnasium. She acted as an advertising hoarding—sailing up and down the Mersey for Lewis's Department Store, who at this point were her owners, before being sold.[10][11] The idea was to attract people to the store by using her as a floating visitor attraction. She was sold at auction in 1888, fetching £16,000 for her value as scrap.[12][13]

An early example of breaking-up a structure by use of a wrecking ball, she was scrapped at New Ferry on the River Mersey by Henry Bath & Son Ltd in 1889–1890—it took 18 months to take her apart. At the time Everton Football Club were looking for a flagpole for their Anfield ground, and consequently purchased her top mast. It still stands there today at the ground—now owned by Liverpool Football Club, at the Kop end.[14] In 2011, the Channel 4 programme Time Team found geophysical survey evidence to suggest that residual iron parts from the ship's keel and lower structure still reside in the foreshore.[15]

During 1859, when Great Eastern was off Portland conducting trials, an explosion aboard blew off one of the funnels. The funnel was salvaged and subsequently purchased by the water company supplying Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in Dorset, UK, and used as a filtering device. It was later transferred to the Bristol Maritime Museum close to Brunel's SS Great Britain then moved to the SS Great Britain museum.

In popular culture

- The SS Great Eastern is the subject of the Sting song, "Ballad of the Great Eastern" from the 2013 album The Last Ship.

- An Atlantic crossing on the SS Great Eastern is the backdrop to Jules Verne's 1871 novel A Floating City

- The SS Great Eastern and its creator Isambard Kingdom Brunel are central to Howard A. Rodman's 2019 novel The Great Eastern, in which Captain Ahab is pitted against Captain Nemo.

- In the trade management video game, Anno 1800 released in 2019 by Ubisoft; the player has the opportunity to construct the Great Eastern as an addition to their naval fleet. The Great Eastern has the largest cargo capacity of any ship in the game with a total of 8 cargo slots.

Gallery

-

On the deck, 1857

-

Great Eastern,

12 November 1857 -

SS Great Eastern's launch ramp at Millwall

-

Print referring to the difficulty of trying to launch Great Eastern, in the collection of The Mariners' Museum

-

Magazine illustration ca. 1877

-

James Henry Pullen's model of SS Great Eastern

-

Part of a funnel from the SS Great Eastern. SS Great Britain Museum, Bristol.

See also

- James Henry Pullen's model of SS Great Eastern

- Steering engine – Great Eastern was the first ship so equipped

- Transatlantic telegraph cable

- List of large sailing vessels

References

- ^ Dawson, Philip S. (2005). The Liner. Chrysalis Books. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-85177-938-6.

- ^ Image:Oscillating engine, and boilers, of Great Eastern - gteast.gif224kB.png

- ^ "Ocean Record Breaking". New York Times. 7 July 1895.

- ^ Wilson, Arthur (1994). The Living Rock: The Story of Metals Since Earliest Times and Their Impact on Civilization. Woodhead Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-85573-301-5.

- ^ Rolt 1957, p. 309

- ^ Rolt 1957, p. 313

- ^ "Brunel's ships p147"

- ^ Brander, Roy. "The RMS Titanic and its Times: When Accountants Ruled the Waves". Elias Kline Memorial Lecture, 69th Shock & Vibration Symposium. Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- ^ Mysterious Humongous Anchor Snagged Big haul for dragger off Montauk Point - October 11, 2007

- ^ S. R. Hill (4 July 2016). The Distributive System: The Commonwealth and International Library: Social Administration, Training, Economics and Production Division. Elsevier. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-1-4831-3777-3.

- ^ Steven Brindle (23 May 2013). Brunel: The Man Who Built the World. Orion Publishing Group. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-1-78022-648-4.

- ^ Paul Graves-Brown; Rodney Harrison; Angela Piccini (17 October 2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World. OUP Oxford. pp. 250–. ISBN 978-0-19-166395-6.

- ^ David Hall; Fred Dibnah (31 March 2013). Fred Dibnah's Age Of Steam. Ebury Publishing. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-1-4481-4140-1.

- ^ "LIVERWEB - An A to Z of Liverpool FC - G". liverweb.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Presenter: Tony Robinson (10 November 2011). "Brunel's Last Launch". Time Team Special. Channel 4.

Further reading

- Wallace, William A. (2014). The Great Eastern's Log: Containing Her First Transatlantic Voyage and All Particulars of Her American Visit. Europaischer Hochschulverlag Gmbh & Co. ISBN 978-3954272662.

- Tyler, David Budlong (1939). Steam Conquers the Atlantic. D. Appleton-Century.

- Emmerson, George S. (1981). S.S. Great Eastern. David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8054-3.

- Gillings, Annabel (2006). Brunel. Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904950-44-8.

- Dugan, James (1953). The Great Iron Ship. Harper. ISBN 978-0-7509-3447-3.

- Rolt, L. T. C. (1957). Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Longmans.

- Verne, Jules (1871). A Floating City. Harper. ISBN 978-0-7509-3447-3. (account of his 1867 voyage on the Great Eastern)

- Cadbury, Deborah (2003). Seven Wonders of the Industrial World. Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-716304-5.

- The Titanic Disaster: An Enduring Example of Money Management vs. Risk Management

- Edited by Andrew Kelly and Melanie Kelly, Brunel – In Love With the Impossible, 2006 by Bristol Cultural Development Partnership, Hardback ISBN 0-9550742-0-7, Paperback ISBN 0-9550742-1-5

External links

- Great Eastern on thegreatoceanliners.com

- The building of the Great Eastern. at Southern Millwall: Drunken Dock and the Land of Promise, pp. 466–480, Survey of London volumes 43 and 44, edited by Hermione Hobhouse, 1994.

- The Great Eastern and Cable Laying

- Brief description of the Great Eastern

- Great Eastern timeline

- SS Great Eastern on Facebook

- First voyage of the Great Eastern[permanent dead link], in The Engineer, 16 September 1859.

- Images of the Great Eastern at the English Heritage Archive

- Maritimequest SS Great Eastern Photo Gallery

- Use dmy dates from September 2013

- Victorian-era passenger ships of the United Kingdom

- Shipbuilding in London

- Steamships of the United Kingdom

- Steamships

- Sailing ships of the United Kingdom

- Six-masted ships

- Ships built in Millwall

- Ships designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

- Cable ships of the United Kingdom

- 1858 ships

- Jules Verne

- Passenger ships of the United Kingdom

- Ships with box type boilers

- 1858 establishments in England

- Maritime incidents in September 1859

- Maritime incidents in August 1862