History of communication

The history of communication technologies (media and appropriate inscription tools) have evolved in tandem with shifts in political and economic systems, and by extension, systems of power. Communication can range from very subtle processes of exchange, to full conversations and mass communication. The history of communication itself can be traced back since the origin of speech circa 500,000 BCE[citation needed]. The use of technology in communication may be considered since the first use of symbols about 30,000 years BCE. Among the symbols used, there are cave paintings, petroglyphs, pictograms and ideograms. Writing was a major innovation, as well as printing technology and, more recently, telecommunications and the Internet.

Primitive times

Human communication was revolutionized with the origin of speech approximately 500,000 BCE[citation needed]. Symbols were developed about 30,000 years ago. The imperfection of speech, which nonetheless allowed easier dissemination of ideas and eventually resulted in the creation of new forms of communications, improving both the range at which could communicate and the longevity of the information. All of those inventions were based on the key concept of the symbol.

The oldest known symbols created for the purpose of communication were cave paintings, a form of rock art, dating to the Upper Paleolithic age. The oldest known cave painting is located within Chauvet Cave, dated to around 30,000 BC.[1] These paintings contained increasing amounts of information: people may have created the first calendar as far back as 15,000 years ago.[2] The connection between drawing and writing is further shown by linguistics: in Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece the concepts and words of drawing and writing were one and the same (Egyptian: 's-sh', Greek: 'graphein').[3]

Petroglyphs

The next advancement in the history of communications came with the production of petroglyphs, carvings into a rock surface. It took about 20,000 years for homo sapiens to move from the first cave paintings to the first petroglyphs, which are dated to approximately the Neolithic and late Upper Paleolithic boundary, about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

It is possible that Homo sapiens (humans) of that time used some other forms of communication, often for mnemonic purposes - specially arranged stones, symbols carved in wood or earth, quipu-like ropes, tattoos, but little other than the most durable carved stones has survived to modern times and we can only speculate about their existence based on our observation of still existing 'hunter-gatherer' cultures such as those of Africa or Oceania.[4]

Pictograms

A pictogram (pictograph) is a symbol representing a concept, object, activity, place or event by illustration. Pictography is a form of proto-writing whereby ideas are transmitted through drawing. Pictographs were the next step in the evolution of communication: the most important difference between petroglyphs and pictograms is that petroglyphs are simply showing an event, but pictograms are telling a story about the event, thus they can for example be ordered chronologically.

Pictograms were used by various ancient cultures all over the world since around 9000 BC, when tokens marked with simple pictures began to be used to label basic farm produce, and become increasingly popular around 6000–5000 BC.

They were the basis of cuneiform [5] and hieroglyphs, and began to develop into logographic writing systems around 5000 BC.

Ideograms

Pictograms, in turn, evolved into ideograms, graphical symbols that represent an idea. Their ancestors, the pictograms, could represent only something resembling their form: therefore a pictogram of a circle could represent a sun, but not concepts like 'heat', 'light', 'day' or 'Great God of the Sun'. Ideograms, on the other hand, could convey more abstract concepts, so that for example an ideogram of two sticks can mean not only 'legs' but also a verb 'to walk'.

Because some ideas are universal, many different cultures developed similar ideograms. For example, an eye with a tear means 'sadness' in Native American ideograms in California, as it does for the Aztecs, the early Chinese and the Egyptians. [citation needed]

Ideograms were precursors of logographic writing systems such as Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters. [citation needed]

Examples of ideographical proto-writing systems, thought not to contain language-specific information, include the Vinca script (see also Tărtăria tablets) and the early Indus script. [citation needed] In both cases there are claims of decipherment of linguistic content, without wide acceptance. [citation needed]

Writing

Early scripts

The oldest-known forms of writing were primarily logographic in nature, based on pictographic and ideographic elements. Most writing systems can be broadly divided into three categories: logographic, syllabic and alphabetic (or segmental); however, all three may be found in any given writing system in varying proportions, often making it difficult to categorise a system uniquely.

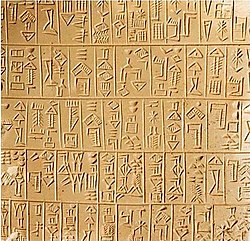

The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age in the late Neolithic of the late 4000 BC. The first writing system is generally believed to have been invented in pre-historic Sumer and developed by the late 3000's BC into cuneiform. Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the undeciphered Proto-Elamite writing system and Indus Valley script also date to this era, though a few scholars have questioned the Indus Valley script's status as a writing system.

The original Sumerian writing system was derived from a system of clay tokens used to represent commodities. By the end of the 4th millennium BC, this had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a round-shaped stylus impressed into soft clay at different angles for recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with pictographic writing using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted. Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing was gradually replaced about 2700–2000 BC by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms, but developed to include phonetic elements by the 2800 BC. About 2600 BC cuneiform began to represent syllables of spoken Sumerian language.

Finally, cuneiform writing became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers. By the 26th century BC, this script had been adapted to another Mesopotamian language, Akkadian, and from there to others such as Hurrian, and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian.

The Chinese script may have originated independently of the Middle Eastern scripts, around the 16th century BC (early Shang Dynasty), out of a late neolithic Chinese system of proto-writing dating back to c. 6000 BC. The pre-Columbian writing systems of the Americas, including Olmec and Mayan, are also generally believed to have had independent origins.

Alphabet

The first pure alphabets (properly, "abjads", mapping single symbols to single phonemes, but not necessarily each phoneme to a symbol) emerged around 2000 BC in Ancient Egypt, but by then alphabetic principles had already been incorporated into Egyptian hieroglyphs for a millennium (see Middle Bronze Age alphabets).

By 2700 BC, Egyptian writing had a set of some 22 hieroglyphs to represent syllables that begin with a single consonant of their language, plus a vowel (or no vowel) to be supplied by the native speaker. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names.

However, although seemingly alphabetic in nature, the original Egyptian uniliterals were not a system and were never used by themselves to encode Egyptian speech. In the Middle Bronze Age an apparently "alphabetic" system is thought by some to have been developed in central Egypt around 1700 BC for or by Semitic workers, but we cannot read these early writings and their exact nature remains open to interpretation.

Over the next five centuries this Semitic "alphabet" (really a syllabary like Phoenician writing) seems to have spread north. All subsequent alphabets around the world[citation needed] with the sole exception of Korean Hangul have either descended from it, or been inspired by one of its descendants.

Scholars agree that there is a relationship between the West-Semetic alphabet and the creation of the Greek alphabet. There is debate between scholars regarding the earliest uses of the Greek alphabet because of the changes that were made to create the Greek alphabet.[6]

The Greek alphabet had the following characteristics:

- The Greek lettering we know of today traces back to the eighth century B.C.

- Early Greek scripts used the twenty-two West-Semetic letters, and included five supplementary letters.

- Early Greek was not uniform in structure, and had many local variations.

- The Greek lettering was written using a lapidary style of writing.

- Greek was written in a boustrophedon style.

Scholars believe that at one point in time, early Greek scripts were very close to the West-Semetic alphabet. Over time, the changes that were made to the Greek alphabet were introduced as a result of the need for the Greeks to find a better way to express their spoken language in a more accurate way.[6]

Storytelling

Verbal communication is one of the earliest forms of human communication, the oral tradition of storytelling has dated back to various times in history. The development of communication in its oral form can be categorized based on certain historical periods. The complexity of oral communication has always been reflective based on the circumstance of the time period. Verbal communication was never bound to one specific area, instead, it had and continues to be a globally shared tradition of communication.[7] People communicated through song, poems, and chants, as some examples. People would gather in groups and pass down stories, myths, and history. Oral poets from Indo-European regions were known as "weavers of words" for their mastery over the spoken word and ability to tell stories.[8] Nomadic people also had oral traditions that they used to tell stories of the history of their people to pass them on to the next generation.

Nomadic tribes have been the torch bearers of oral storytelling. Nomads of Arabia are one example of the many nomadic tribes that have continued through history to use oral storytelling as a tool to tell their histories and the story of their people. Due to the nature of nomadic life, these individuals were often left without architecture and possessions to call their own, and often left little to no traces of themselves.[9] The richness of the nomadic life and culture is preserved by early Muslim scholars who collect the poems and stories that are handed down from generation to generation. Poems created by these Arabic nomads are passed down by specialists known as sha'ir. These individuals spread the stories and histories of these nomadic tribes, and often in times of war, would strengthen morale within members of given tribes through these stories.[citation needed]

In its natural form, oral communication was, and has continued to be, one of the best ways for humans to spread their message, history, and traditions to the world.[citation needed]

Timeline of writing technology

- 30,000 BC – In ice-age Europe, people mark ivory, bone, and stone with patterns to keep track of time, using a lunar calendar.[10]

- 14,000 BC – In what is now Mezhirich, Ukraine, the first known artifact with a map on it is made using bone.[10]

- Prior to 3500 BC – Communication was carried out through paintings of indigenous tribes.

- 3500s BC – The Sumerians develop cuneiform writing and the Egyptians develop hieroglyphic writing.

- 16th century BC – The Phoenicians develop an alphabet.

- 105 – Tsai Lun invents paper.

- 7th century – Hindu-Malayan empires write legal documents on copper plate scrolls, and write other documents on more perishable media.

- 751 – Paper is introduced to the Muslim world after the Battle of Talas.

- 1250 – The quill is used for writing.[10]

Timeline of printing technology

- 1305 – The Chinese develop wooden block movable type printing.

- 1450 – Johannes Gutenberg invents a printing press with metal movable type.

- 1844 – Charles Fenerty produces paper from a wood pulp, eliminating rag paper which was in limited supply.

- 1849 – Associated Press organizes Nova Scotia pony express to carry latest European news for New York newspapers.

- 1958 – Chester Carlson presents the first photocopier suitable for office use.

History of telecommunication

The history of telecommunication - the transmission of signals over a distance for the purpose of communication - began thousands of years ago with the use of smoke signals and drums in Africa, America and parts of Asia. In the 1790s the first fixed semaphore systems emerged in Europe however it was not until the 1830s that electrical telecommunication systems started to appear.

Pre-electric

- AD 26–37 – Roman Emperor Tiberius rules the empire from the island of Capri by signaling messages with metal mirrors to reflect the sun.

- 1520 – Ships on Ferdinand Magellan's voyage signal to each other by firing cannon and raising flags.

Telegraph

- 1792 – Claude Chappe establishes the first long-distance semaphore telegraph line.

- 1831 – Joseph Henry proposes and builds an electric telegraph.

- 1836 – Samuel Morse develops the Morse code.

- 1843 – Samuel Morse builds the first long distance electric telegraph line.

Landline telephone

- 1876 – Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas A. Watson exhibit an electric telephone in Boston.

- 1889 – Almon Strowger patents the direct dial

Phonograph

- 1877 – Thomas Edison patents the phonograph.

Radio and television

- 1920 – Radio station KDKA based in Pittsburgh began the first broadcast.

- 1925 – John Logie Baird transmits the first television signal.

- 1942 – Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil invent frequency hopping spread spectrum communication technique.

- 1947 – Full-scale commercial television is first broadcast.

- 1963 – First geosynchronous communications satellite is launched, 17.5 years after Arthur C. Clarke's article.

- 1999 – Sirius satellite radio is introduced.

Fax

- 1843 – Patent issued for the "Electric Printing Telegraph", a very early forerunner of the fax machine

- 1926 – Commercial availability of the radiofax

- 1964 – First modern fax machine commercially available (Long Distance Xerography)

Mobile telephone

- 1947 – Douglas H. Ring and W. Rae Young of Bell Labs propose a cell-based approach which led to "cellular phones."

- 1981 – Nordic Mobile Telephone, the world's first automatic mobile phone is put into operation

- 1991 – GSM is put into operation

- 1992 – Neil Papworth sends the first SMS (or text message).

- 1999 – 45% of Australians have a mobile phone.

Computers and Internet

- 1949 – Claude Elwood Shannon, the "father of information theory", mathematically proves the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem.

- 1965 – First email sent (at MIT).[11]

- 1966 – Charles Kao realizes that silica-based optical waveguides offer a practical way to transmit light via total internal reflection.

- 1969 – The first hosts of ARPANET, Internet's ancestor, are connected.[12]

- 1971 – Erna Schneider Hoover invent a computerized switching system for telephone traffic.

- 1971 – 8-inch floppy disk removable storage medium for computers is introduced.[13]

- 1975 – "First list servers are introduced."[13]

- 1976 – The personal computer (PC) market is born.

- 1977 – Donald Knuth begins work on TeX.

- 1981 – Hayes Smartmodem introduced.[14]

- 1983 – Microsoft Word software is launched.[15]

- 1985 – AOL is launched.

- 1989 – Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau build the prototype system which became the World Wide Web at CERN.

- 1989 – WordPerfect 5.1 word processing software released.[14]

- 1989 – Lotus Notes software is launched.[16]

- 1991 – Anders Olsson transmits solitary waves through an optical fiber with a data rate of 32 billion bits per second.

- 1992 – Internet2 organization is created.

- 1992 – IBM ThinkPad 700C laptop computer created. It was lightweight compared to its predecessors.[14]

- 1993 – Mosaic graphical web browser is launched.[16]

- 1994 – Internet radio broadcasting is born.

- 1996 – Motorola StarTAC mobile phone introduced. It was significantly smaller than previous cellphones.[14]

- 1997 – SixDegrees.com is launched, the first of a number of early social networking services

- 1999 – Napster peer-to-peer file sharing is launched.[14]

- 2001 – Cyworld adds social networking features and becomes the first of a number of mass-market social networking service

- 2003 – Skype video calling software is launched.

- 2004 – Facebook is launched, becoming the largest social networking site in 2009.

- 2005 – YouTube, the video sharing site, is launched.

- 2006 – Twitter is launched.

- 2007 – iPhone is launched.

- 2009 – Whatsapp is launched.

- 2010 – Instagram is launched.

- 2011 – Snapchat is launched.

- 2015 – Discord is launched.

See also

- List of years in home video

- Timeline of photography technology

- Category:Computing timelines

- Historical linguistics

- Babylonokia (art piece featuring a cuneiform mobile phone keyboard)

References

- ^ Paul Martin Lester, Visual Communication with Infotrac: Images with Messages, Thomson Wadsworth, 2005, ISBN 0-534-63720-5, Google Print: p.48

- ^ according to a claim by Michael Rappenglueck, of the University of Munich (2000) [1]

- ^ David Diringer, The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Courier Dover Publications, 1982, ISBN 0-486-24243-9, Google Print: p.27

- ^ David Diringer, History of the Alphabet, 1977; ISBN 0-905418-12-3.

- ^ "Linguistics 201: The Invention of Writing". Pandora.cii.wwu.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-07-21. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ^ a b Naveh, Joseph (1973). "Some Semitic Epigraphical Considerations on the Antiquity of the Greek Alphabet". American Journal of Archaeology. 77 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2307/503227. JSTOR 503227.

- ^ Panini, et al. Fiorini, R, et al. F (March–April 2015). "Oral communication: short history and some rules". Giornale Italiano di Nefrologia. 32 (2). PMID 26005935.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Woodward, Roger. http://worldcat.org/oclc/875096147. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107731905.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ "History of the Arabs". History World.

- ^ a b c "Invention and Technology". Volume Library 1. The Southwestern Company. 2009. pp. 9–15.

- ^ Tom Van Vleck (2001), "History of Electronic Mail", Multicians.org

- ^ Anton A. Huurdeman (2003). "Chronology". Worldwide History of Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-20505-0.

- ^ a b Cornell University Library (2003). "Digital Preservation and Technology Timeline". Digital Preservation Management. Archived from the original on 2015-08-06. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- ^ a b c d e Christopher Null (April 2, 2007). "The 50 Best Tech Products of All Time". PC World.

- ^ Paul Ford (April 2014), The Great Works of Software – via Medium

- ^ a b Matthew Kirschenbaum (July 2013), "10 Most Influential Software Programs Ever", Slate, USA

- (in Polish) Piotr Konieczny, Komunikacja: od mowy do Internetu, Histmag #49

Further reading

- Asante, Molefi Kete, Yoshitaka Miike, and Jing Yin, eds. The global intercultural communication reader (Routledge, 2014)

- Berger, Arthur Asa. Media and communication research methods: An introduction to qualitative and quantitative approaches (SAGE 2013)

- Briggs, Asa, and Peter Burke. A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet. Cambridge: Polity, 2002.

- Burke, Peter. A Social History of Knowledge: From Gutenberg to Diderot (2000)

- Burke, Peter. A Social History of Knowledge II: From the Encyclopaedia to Wikipedia (2012)

- de Mooij, Marieke. "Theories of Mass Communication and Media Effects Across Cultures." in Human and Mediated Communication around the World (Springer 2014) pp 355–393.

- Esser, Frank, and Thomas Hanitzsch, eds. The handbook of comparative communication research (Routledge, 2012)

- Gleick, James (2011). The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. ISBN 978-0-375-42372-7.

- Jensen, Klaus Bruhn, ed. A handbook of media and communication research: qualitative and quantitative methodologies (Routledge, 2013)

- Paxson, Peyton. Mass Communications and Media Studies: An Introduction (Bloomsbury, 2010)

- Poe, Marshall T. A History of Communications: Media and Society From the Evolution of Speech to the Internet (Cambridge University Press; 2011) 352 pages; Documents how successive forms of communication are embraced and, in turn, foment change in social institutions.

- Schramm, Wilbur. Mass Communications (1963)

- Schramm, Wilbur, ed. Mass Communications: A Reader (1960)

- Simonson, Peter. Refiguring Mass Communication: A History (2010)