Strange Fruit

| "Strange Fruit" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Billie Holiday | ||||

| B-side | "Fine and Mellow" | |||

| Released | 1939 | |||

| Recorded | April 20, 1939[1] | |||

| Genre | Blues, jazz | |||

| Length | 3:02 | |||

| Label | Commodore | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Abel Meeropol | |||

| Producer(s) | Milt Gabler | |||

| Billie Holiday singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

"Strange Fruit" | ||||

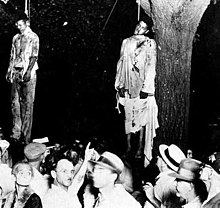

"Strange Fruit" is a song recorded by Billie Holiday in 1939, written by Abel Meeropol and published in 1937. It protests the lynching of Black Americans, with lyrics that compare the victims to the fruit of trees. Such lynchings had reached a peak in the Southern United States at the turn of the 20th century, and the great majority of victims were black.[2] The song has been called "a declaration of war" and "the beginning of the civil rights movement".[3]

Meeropol set his lyrics to music with his wife and singer Laura Duncan and performed it as a protest song in New York City venues in the late 1930s, including Madison Square Garden. The song has been covered by numerous artists, including Nina Simone, UB40, Jeff Buckley, Cocteau Twins, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Robert Wyatt, and Dee Dee Bridgewater. Diana Ross recorded the song for her debut film, the Billie Holiday biopic Lady Sings the Blues (1972), and it was included on the chart topping soundtrack album. Holiday's version was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1978.[4] It was also included in the "Songs of the Century" list of the Recording Industry of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.[5]

Poem and song

"Strange Fruit" originated as a poem written by Jewish-American writer, teacher and songwriter Abel Meeropol, under his pseudonym Lewis Allan, as a protest against lynchings.[6][7][8] In the poem, Meeropol expressed his horror at lynchings, inspired by Lawrence Beitler's photograph of the 1930 lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana.[7]

Meeropol published the poem under the title "Bitter Fruit" in January 1937 in The New York Teacher, a union magazine of the Teachers Union.[9][10] Though Meeropol had asked others (notably Earl Robinson) to set his poems to music, he set "Strange Fruit" to music himself. First performed by Meeropol's wife and their friends in social contexts,[10] his protest song gained a certain success in and around New York. Meeropol, his wife, and black vocalist Laura Duncan performed it at Madison Square Garden.[11]

The lyrics are under copyright but have been republished in full in an academic journal, with permission.[12]

Billie Holiday's performances and recordings

One version of events claims that Barney Josephson, the founder of Café Society in Greenwich Village, New York's first integrated nightclub, heard the song and introduced it to Billie Holiday. Other reports say that Robert Gordon, who was directing Billie Holiday's show at Café Society, heard the song at Madison Square Garden and introduced it to her.[9] Holiday first performed the song at Café Society in 1939. She said that singing it made her fearful of retaliation but, because its imagery reminded her of her father, she continued to sing the piece, making it a regular part of her live performances.[14] Because of the power of the song, Josephson drew up some rules: Holiday would close with it; the waiters would stop all service in advance; the room would be in darkness except for a spotlight on Holiday's face; and there would be no encore.[9] During the musical introduction to the song, Holiday stood with her eyes closed, as if she were evoking a prayer.

Holiday approached her recording label, Columbia, about the song, but the company feared reaction by record retailers in the South, as well as negative reaction from affiliates of its co-owned radio network, CBS.[15] When Holiday's producer John Hammond also refused to record it, she turned to her friend Milt Gabler, owner of the Commodore label.[16] Holiday sang "Strange Fruit" for him a cappella, and moved him to tears. Columbia gave Holiday a one-session release from her contract so she could record it; Frankie Newton's eight-piece Café Society Band was used for the session. Because Gabler worried the song was too short, he asked pianist Sonny White to improvise an introduction. On the recording, Holiday starts singing after 70 seconds.[9] It was recorded on April 20, 1939.[17] Gabler worked out a special arrangement with Vocalion Records to record and distribute the song.[18]

Holiday recorded two major sessions of the song at Commodore, one in 1939 and one in 1944. The song was highly regarded; the 1939 recording eventually sold a million copies,[7] in time becoming Holiday's biggest-selling recording.

In her 1956 autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, Holiday suggested that she, together with Meeropol, her accompanist Sonny White, and arranger Danny Mendelsohn, set the poem to music. The writers David Margolick and Hilton Als dismissed that claim in their work Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song, writing that hers was "an account that may set a record for most misinformation per column inch". When challenged, Holiday—whose autobiography had been ghostwritten by William Dufty—claimed, "I ain't never read that book."[19]

Billie Holiday was so well known for her rendition of "Strange Fruit" that "she crafted a relationship to the song that would make them inseparable".[20] Holiday's 1939 version of the song was included in the National Recording Registry on January 27, 2003.

In October 1939, Samuel Grafton of the New York Post said of "Strange Fruit", "If the anger of the exploited ever mounts high enough in the South, it now has its Marseillaise."[21] In an attempt to have a two-thirds majority in the Senate that would break the filibusters by the southern senators, anti-racism activists were encouraged to mail copies of "Strange Fruit" to their senators.[22]

Notable covers

Notable cover versions of this song include Nina Simone (whose version was sampled in Kanye West's "Blood on the Leaves"[23]), René Marie,[23] Jeff Buckley,[23] Cocteau Twins,[24] Siouxsie and the Banshees,[25] Dee Dee Bridgewater,[25] Josh White,[26] UB40,[25] Bettye LaVette[27] and Edward W. Hardy.[28] Nina Simone recorded the song in 1965,[29] a recording described by journalist David Margolick in the New York Times as featuring a "plain and unsentimental voice".[23] Journalist Lara Pellegrinelli wrote that Jeff Buckley while singing it "seems to meditate on the meaning of humanity the way Walt Whitman did, considering all of its glorious and horrifying possibilities".[23] Rene Marie's rendition was coupled with Confederate anthem "Dixie", making for an "uncomfortable juxtaposition", according to Pellegrinelli.[23] LA Times noted that Siouxsie and the Banshees's version contained "a solemn string section behind the vocals" and "a bridge of New Orleans funeral-march jazz" which enhanced the singer's "evocative interpretation".[30] The group's rendition was selected by the Mojo magazine staff to be included on the compilation Music Is Love: 15 Tracks That Changed The World .[31][32]

Awards and honors

- 1999: Time magazine named "Strange Fruit" as "Best Song of the Century" in its issue dated December 31, 1999.[33][34]

- 2002: The Library of Congress honored the song as one of 50 recordings chosen that year to add to the National Recording Registry.[35]

- 2010: The New Statesman listed it as one of the "Top 20 Political Songs".[36]

- 2011: The Atlanta Journal-Constitution listed the song as Number One on "100 Songs of the South".[37]

Fiction

- Lillian Smith's novel Strange Fruit (1944) was said to have been inspired by Holiday's version of the song.[38]

Bibliography

(Harper Collins). I

- Margolick, David (2001). Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0060959562.

- Clarke, Donald (1995). Billie Holiday: Wishing on the Moon. München: Piper. ISBN 978-3-492-03756-3.

- Davis, Angela (1999). Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-77126-5.

- Holiday, Billie; Dufty, William (1992). Lady Sings the Blues. Edition Nautilus. ISBN 978-3-89401-110-9. Autobiography.

References

- ^ "Billie Holiday recording sessions". Billieholidaysongs.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (New York, 1944), page 561.

- ^ "Review: Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights", The New York Times, 2000.

- ^ "Hall of Fame". Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Songs of the Century", CNN, March 7, 2001.

- ^ Margolick, David (2000). Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights. Philadelphia: Running Press. pp. 25–27.

- ^ a b c Moore, Edwin (September 18, 2010). "Strange Fruit is still a song for today". The Guardian. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (Host) (September 5, 2012). "The Strange Story of the Man Behind 'Strange Fruit'". Morning Edition. NPR.

- ^ a b c d Lynskey, Dorian (2011). "33 Revolutions Per Minute". London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24134-7.

- ^ a b Carvalho, John M. (2013). "'Strange Fruit': Music between Violence and Death". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 71 (1): 111–119 at 111–112. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2012.01547.x. ISSN 0021-8529. JSTOR 23597541.

- ^ Margolick, Strange Fruit, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Meeropol, Abel (July 12, 2006). "Strange fruit". International Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (4): 902. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl173. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Strange Fruit: Anniversary Of A Lynching". NPR. August 6, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Margolick, Strange Fruit, pp. 40–46.

- ^ Margolick, Strange Fruit, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Billy Crystal (2004). 700 Sundays. HBO. OCLC 112. 700 Sundays at IMDb.

- ^ Aida Amoako, "Strange Fruit: The most shocking song of all time?", Songs that made history, BBC. April 17, 2019.

- ^ Billy Crystal, 700 Sundays, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Margolick, Strange Fruit, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Perry, Samuel (2012). ""Strange Fruit," Ekphrasis, and the Lynching Scene". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 43:5 (5): 449–474. doi:10.1080/02773945.2013.839822. S2CID 144222928.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (February 15, 2011). "Strange Fruit: the first great protest song". The Guardian.

- ^ Margolick, Strange Fruit, p. 77

- ^ a b c d e f Pellegrinelli, Lara (June 22, 2009). "Evolution Of A Song: 'Strange Fruit'". npr.org. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ com, cocteautwins. "Discography: BBC Sessions". cocteautwins.com.

- ^ a b c Margolick, Strange Fruit, p. 24

- ^ gov, loc. "Josh White:Strange Fruit". loc.gov. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ Bettye LaVette Unleashes Cover of Billie Holiday’s ‘Strange Fruit’, Claire Shaffer, Rolling Stone, June 12, 2020.

- ^ BWW News Desk, "Video: Listen To Edward W. Hardy's Haunting String Quartet Arrangement Of 'Strange Fruit'", BroadwayWorld, June 24, 2020.

- ^ Aida Amoako (April 17, 2019). "Strange Fruit: The most shocking song of all time". BBC. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Atkinson, Terry (March 15, 1987). "Siouxsie Looks Back". L.A. Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Music Is Love! (15 Tracks That Changed The World) CD". Mojo. June 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2017. Siouxsie and the Banshes's rendition from their 1987 Through the Looking Glass album was selected to feature on this compilation

- ^ Hasse, John Edward (April 30, 2019). "'Strange Fruit': Still Haunting at 80". Walt Street Journal. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Billy Crystal, 700 Sundays, p. 47.

- ^ McNally, Owen (March 30, 2000). "'Song of the century' chilling: Graphic lyrics of 'the first unmuted cry against racism' are making a comeback". Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ "National Recording Registry 2002". loc.gov. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Ian K (March 25, 2010). "Top 20 Political Songs: Strange Fruit". New Statesman. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "100 Songs of the South | accessAtlanta.com". Alt.coxnewsweb.com. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Bass, Erin Z. (December 12, 2012). "The Strange Life of Strange Fruit". Deep South Magazine.

External links

- "Strange Fruit", Independent Lens, PBS

- Strange Fruit, Newsreel documentary

- "Strange Fruit", Shmoop, analysis of lyrics, historical and literary allusions - student & teaching guide

- Template:MetroLyrics song

- "Strange Fruit" at MusicBrainz (information and list of recordings)

- BBC Radio 4 - Soul Music, Series 17, Strange Fruit

- "Strange Fruit: A protest song with enduring relevance"

- "Strange Fruit". Radio Diaries (Podcast). PRX. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- 1939 songs

- Billie Holiday songs

- Songs about trees

- Lynching in the United States

- History of African-American civil rights

- Songs against racism and xenophobia

- Songs based on actual events

- Songs based on poems

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- Works originally published in American magazines

- Protest songs

- Songs about the American South