Gram-positive bacteria

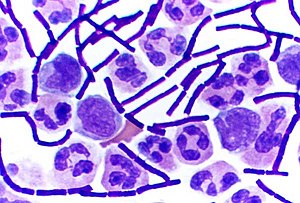

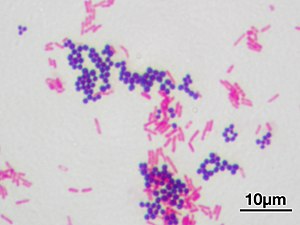

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

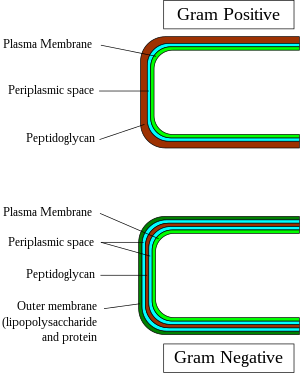

Gram-positive bacteria take up the crystal violet stain used in the test, and then appear to be purple-coloured when seen through an optical microscope. This is because the thick peptidoglycan layer in the bacterial cell wall retains the stain after it is washed away from the rest of the sample, in the decolorization stage of the test.

Conversely, gram-negative bacteria cannot retain the violet stain after the decolorization step; alcohol used in this stage degrades the outer membrane of gram-negative cells, making the cell wall more porous and incapable of retaining the crystal violet stain. Their peptidoglycan layer is much thinner and sandwiched between an inner cell membrane and a bacterial outer membrane, causing them to take up the counterstain (safranin or fuchsine) and appear red or pink.

Despite their thicker peptidoglycan layer, gram-positive bacteria are more receptive to certain cell wall targeting antibiotics than gram-negative bacteria, due to the absence of the outer membrane.[1]

Characteristics

In general, the following characteristics are present in gram-positive bacteria:[2]

- Cytoplasmic lipid membrane

- Thick peptidoglycan layer

- Teichoic acids and lipoids are present, forming lipoteichoic acids, which serve as chelating agents, and also for certain types of adherence.

- Peptidoglycan chains are cross-linked to form rigid cell walls by a bacterial enzyme DD-transpeptidase.

- A much smaller volume of periplasm than that in gram-negative bacteria.

Only some species have a capsule, usually consisting of polysaccharides. Also, only some species are flagellates, and when they do have flagella, have only two basal body rings to support them, whereas gram-negative have four. Both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria commonly have a surface layer called an S-layer. In gram-positive bacteria, the S-layer is attached to the peptidoglycan layer. Gram-negative bacteria's S-layer is attached directly to the outer membrane. Specific to gram-positive bacteria is the presence of teichoic acids in the cell wall. Some of these are lipoteichoic acids, which have a lipid component in the cell membrane that can assist in anchoring the peptidoglycan.

Classification

Along with cell shape, Gram staining is a rapid method used to differentiate bacterial species. Such staining, together with growth requirement and antibiotic susceptibility testing, and other macroscopic and physiologic tests, forms the full basis for classification and subdivision of the bacteria (e.g., see figure and pre-1990 versions of Bergey's Manual).

Historically, the kingdom Monera was divided into four divisions based primarily on Gram staining: Bacillota (positive in staining), Gracilicutes (negative in staining), Mollicutes (neutral in staining) and Mendocutes (variable in staining).[3] Based on 16S ribosomal RNA phylogenetic studies of the late microbiologist Carl Woese and collaborators and colleagues at the University of Illinois, the monophyly of the gram-positive bacteria was challenged,[4] with major implications for the therapeutic and general study of these organisms. Based on molecular studies of the 16S sequences, Woese recognised twelve bacterial phyla. Two of these were gram-positive and were divided on the proportion of the guanine and cytosine content in their DNA. The high G + C phylum was made up of the Actinobacteria and the low G + C phylum contained the Firmicutes.[4] The Actinomycetota include the Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Nocardia and Streptomyces genera. The (low G + C) Bacillota, have a 45–60% GC content, but this is lower than that of the Actinomycetota.[2]

Importance of the outer cell membrane in bacterial classification

Although bacteria are traditionally divided into two main groups, gram-positive and gram-negative, based on their Gram stain retention property, this classification system is ambiguous as it refers to three distinct aspects (staining result, envelope organization, taxonomic group), which do not necessarily coalesce for some bacterial species.[5][6][7][8] The gram-positive and gram-negative staining response is also not a reliable characteristic as these two kinds of bacteria do not form phylogenetic coherent groups.[5] However, although Gram staining response is an empirical criterion, its basis lies in the marked differences in the ultrastructure and chemical composition of the bacterial cell wall, marked by the absence or presence of an outer lipid membrane.[5][9]

All gram-positive bacteria are bounded by a single-unit lipid membrane, and, in general, they contain a thick layer (20–80 nm) of peptidoglycan responsible for retaining the Gram stain. A number of other bacteria—that are bounded by a single membrane, but stain gram-negative due to either lack of the peptidoglycan layer, as in the mycoplasmas, or their inability to retain the Gram stain because of their cell wall composition—also show close relationship to the Gram-positive bacteria. For the bacterial cells bounded by a single cell membrane, the term monoderm bacteria has been proposed.[5][9]

In contrast to gram-positive bacteria, all typical gram-negative bacteria are bounded by a cytoplasmic membrane and an outer cell membrane; they contain only a thin layer of peptidoglycan (2–3 nm) between these membranes. The presence of inner and outer cell membranes defines a new compartment in these cells: the periplasmic space or the periplasmic compartment. These bacteria have been designated as diderm bacteria.[5][9] The distinction between the monoderm and diderm bacteria is supported by conserved signature indels in a number of important proteins (viz. DnaK, GroEL).[5][6][9][10] Of these two structurally distinct groups of bacteria, monoderms are indicated to be ancestral. Based upon a number of observations including that the gram-positive bacteria are the major producers of antibiotics and that, in general, gram-negative bacteria are resistant to them, it has been proposed that the outer cell membrane in gram-negative bacteria (diderms) has evolved as a protective mechanism against antibiotic selection pressure.[5][6][9][10] Some bacteria, such as Deinococcus, which stain gram-positive due to the presence of a thick peptidoglycan layer and also possess an outer cell membrane are suggested as intermediates in the transition between monoderm (gram-positive) and diderm (gram-negative) bacteria.[5][10] The diderm bacteria can also be further differentiated between simple diderms lacking lipopolysaccharide, the archetypical diderm bacteria where the outer cell membrane contains lipopolysaccharide, and the diderm bacteria where outer cell membrane is made up of mycolic acid.[7][10][11]

Exceptions

In general, gram-positive bacteria are monoderms and have a single lipid bilayer whereas gram-negative bacteria are diderms and have two bilayers. Some taxa lack peptidoglycan (such as the class Mollicutes, some members of the Rickettsiales, and the insect-endosymbionts of the Enterobacteriales) and are gram-variable. This, however, does not always hold true. The Deinococcota have gram-positive stains, although they are structurally similar to gram-negative bacteria with two layers. The Chloroflexota have a single layer, yet (with some exceptions[12]) stain negative.[13] Two related phyla to the Chloroflexi, the TM7 clade and the Ktedonobacteria, are also monoderms.[14][15]

Some Bacillota species are not gram-positive. These belong to the class Mollicutes (alternatively considered a class of the phylum Mycoplasmatota), which lack peptidoglycan (gram-indeterminate), and the class Negativicutes, which includes Selenomonas and stain gram-negative.[11] Additionally, a number of bacterial taxa (viz. Negativicutes, Fusobacteriota, Synergistota, and Elusimicrobiota) that are either part of the phylum Bacillota or branch in its proximity are found to possess a diderm cell structure.[8][10][11] However, a conserved signature indel (CSI) in the HSP60 (GroEL) protein distinguishes all traditional phyla of gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonadota, Aquificota, Chlamydiota, Bacteroidota, Chlorobiota, "Cyanobacteria", Fibrobacterota, Verrucomicrobiota, Planctomycetota, Spirochaetota, Acidobacteriota, etc.) from these other atypical diderm bacteria, as well as other phyla of monoderm bacteria (e.g., Actinomycetota, Bacillota, Thermotogota, Chloroflexota, etc.).[10] The presence of this CSI in all sequenced species of conventional LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-containing gram-negative bacterial phyla provides evidence that these phyla of bacteria form a monophyletic clade and that no loss of the outer membrane from any species from this group has occurred.[10]

Pathogenicity

In the classical sense, six gram-positive genera are typically pathogenic in humans. Two of these, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus, are cocci (sphere-shaped). The remaining organisms are bacilli (rod-shaped) and can be subdivided based on their ability to form spores. The non-spore formers are Corynebacterium and Listeria (a coccobacillus), whereas Bacillus and Clostridium produce spores.[16] The spore-forming bacteria can again be divided based on their respiration: Bacillus is a facultative anaerobe, while Clostridium is an obligate anaerobe.[17] Also, Rathybacter, Leifsonia, and Clavibacter are three gram-positive genera that cause plant disease. Gram-positive bacteria are capable of causing serious and sometimes fatal infections in newborn infants.[18] Novel species of clinically relevant gram-positive bacteria also include Catabacter hongkongensis, which is an emerging pathogen belonging to Bacillota.[19]

Bacterial transformation

Transformation is one of three processes for horizontal gene transfer, in which exogenous genetic material passes from a donor bacterium to a recipient bacterium, the other two processes being conjugation (transfer of genetic material between two bacterial cells in direct contact) and transduction (injection of donor bacterial DNA by a bacteriophage virus into a recipient host bacterium).[20] In transformation, the genetic material passes through the intervening medium, and uptake is completely dependent on the recipient bacterium.[20]

As of 2014 about 80 species of bacteria were known to be capable of transformation, about evenly divided between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria; the number might be an overestimate since several of the reports are supported by single papers.[20] Transformation among gram-positive bacteria has been studied in medically important species such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus sanguinis and in gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus.[21]

Orthographic note

The adjectives Gram-positive and Gram-negative derive from the surname of Hans Christian Gram; as eponymous adjectives, their initial letter can be either capital G or lower-case g, depending on which style guide (e.g., that of the CDC), if any, governs the document being written.[22] This is further explained at Gram staining § Orthographic note.

References

- ^ Basic Biology (18 March 2016). "Bacteria".

- ^ a b Madigan, Michael T.; Martinko, John M. (2006). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0131443297.

- ^ Gibbons, N. E.; Murray, R. G. E. (1978). "Proposals Concerning the Higher Taxa of Bacteria". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 28 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1099/00207713-28-1-1.

- ^ a b Woese, C. R. (1987). "Bacterial evolution". Microbiological Reviews. 51 (2): 221–271. doi:10.1128/MMBR.51.2.221-271.1987. PMC 373105. PMID 2439888.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gupta, R. S. (1998). "Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: A reappraisal of evolutionary relationships among archaebacteria, eubacteria and eukaryotes". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 62 (4): 1435–1491. doi:10.1128/MMBR.62.4.1435-1491.1998. PMC 98952. PMID 9841678.

- ^ a b c Gupta, R. S. (2000). "The natural evolutionary relationships among prokaryotes" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 26 (2): 111–131. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.496.1356. doi:10.1080/10408410091154219. PMID 10890353. S2CID 30541897.

- ^ a b Desvaux, M.; Hébraud, M.; Talon, R.; Henderson, I. R. (2009). "Secretion and subcellular localizations of bacterial proteins: A semantic awareness issue". Trends in Microbiology. 17 (4): 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.01.004. PMID 19299134.

- ^ a b Sutcliffe, I. C. (2010). "A phylum level perspective on bacterial cell envelope architecture". Trends in Microbiology. 18 (10): 464–470. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.005. PMID 20637628.

- ^ a b c d e Gupta, R. S. (1998). "What are archaebacteria: life's third domain or monoderm prokaryotes related to Gram-positive bacteria? A new proposal for the classification of prokaryotic organisms". Molecular Microbiology. 29 (3): 695–707. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00978.x. PMID 9723910. S2CID 41206658.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gupta, R. S. (2011). "Origin of diderm (gram-negative) bacteria: antibiotic selection pressure rather than endosymbiosis likely led to the evolution of bacterial cells with two membranes". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 100 (2): 171–182. doi:10.1007/s10482-011-9616-8. PMC 3133647. PMID 21717204.

- ^ a b c Marchandin, H.; Teyssier, C.; Campos, J.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Roger, F.; Gay, B.; Carlier, J.-P.; Jumas-Bilak, E. (2009). "Negativicoccus succinicivorans gen. Nov., sp. Nov., isolated from human clinical samples, emended description of the family Veillonellaceae and description of Negativicutes classis nov., Selenomonadales ord. nov. and Acidaminococcaceae fam. nov. In the bacterial phylum Firmicutes". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 60 (6): 1271–1279. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.013102-0. PMID 19667386.

- ^ Yabe, S.; Aiba, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Hazaka, M.; Yokota, A. (2010). "Thermogemmatispora onikobensis gen. nov., sp. nov. And Thermogemmatispora foliorum sp. nov., isolated from fallen leaves on geothermal soils, and description of Thermogemmatisporaceae fam. nov. and Thermogemmatisporales ord. Nov. Within the class Ktedonobacteria". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 61 (4): 903–910. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.024877-0. PMID 20495028.

- ^ Sutcliffe, I. C. (2011). "Cell envelope architecture in the Chloroflexi: A shifting frontline in a phylogenetic turf war". Environmental Microbiology. 13 (2): 279–282. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02339.x. PMID 20860732.

- ^ Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G. W.; Webb, R. I.; Wagner, A. M.; Blackall, L. L. (2001). "Investigation of Candidate Division TM7, a Recently Recognized Major Lineage of the Domain Bacteria with No Known Pure-Culture Representatives". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 67 (1): 411–419. Bibcode:2001ApEnM..67..411H. doi:10.1128/AEM.67.1.411-419.2001. PMC 92593. PMID 11133473.

- ^ Cavaletti, L.; Monciardini, P.; Bamonte, R.; Schumann, P.; Rohde, M.; Sosio, M.; Donadio, S. (2006). "New Lineage of Filamentous, Spore-Forming, Gram-Positive Bacteria from Soil". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (6): 4360–4369. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.4360C. doi:10.1128/AEM.00132-06. PMC 1489649. PMID 16751552.

- ^ Gladwin, Mark; Trattler, Bill (2007). Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple. Miami, Florida: MedMaster. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-940780-81-1.

- ^ Sahebnasagh, R.; Saderi, H.; Owlia, P. (4–7 September 2011). Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from clinical samples in Tehran by detection of the mecA and nuc genes. The First Iranian International Congress of Medical Bacteriology. Tabriz, Iran.

- ^ MacDonald, Mhairi (2015). Avery's Neonatology: Pathophysiology and Management of the Newborn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 9781451192681. Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Lau, S. K. P.; McNabb, A.; Woo, G. K. S.; Hoang, L.; Fung, A. M. Y.; Chung, L. M. W.; Woo, P. C. Y.; Yuen, K.-Y. (2006-11-22). "Catabacter hongkongensis gen. nov., sp. nov., Isolated from Blood Cultures of Patients from Hong Kong and Canada". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 45 (2): 395–401. doi:10.1128/jcm.01831-06. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 1829005. PMID 17122022.

- ^ a b c Johnston, C.; Martin, B.; Fichant, G.; Polard, P; Claverys, J. P. (2014). "Bacterial transformation: distribution, shared mechanisms and divergent control". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 12 (3): 181–96. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3199. PMID 24509783. S2CID 23559881.

- ^ Michod, R. E.; Bernstein, H.; Nedelcu, A. M. (2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ^ "Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal Style Guide". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

External links

This article incorporates public domain material from Science Primer. NCBI. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08.

This article incorporates public domain material from Science Primer. NCBI. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08.- 3D structures of proteins associated with plasma membrane of gram-positive bacteria

- 3D structures of proteins associated with outer membrane of gram-positive bacteria