Nordic megalith architecture

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2022) |

Nordic megalith architecture is an ancient architectural style found in Northern Europe, especially Scandinavia and North Germany, that involves large slabs of stone arranged to form a structure. It emerged in northern Europe, predominantly between 3500 and 2800 BC. It was primarily a product of the Funnelbeaker culture. Between 1964 and 1974, Ewald Schuldt in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania excavated over 100 sites of different types: simple dolmens, extended dolmens (also called rectangular dolmens), passage graves, great dolmens, unchambered long barrows, and stone cists. In addition, there are polygonal dolmens and types that emerged later, for example, the Grabkiste and Röse. This nomenclature, which specifically derives from the German, is not used in Scandinavia where these sites are categorised by other, more general, terms, as dolmens (Dysser, Döser), passage graves (Ganggrifter, Jættestuen) and stone cists (Hellekister, Hällkista).

Neolithic monuments are a feature of the culture and ideology of Neolithic communities. Their appearance and function serves as an indicator of their social development.[1]

Context

Neolithic monuments are expressions of the culture and beliefs of Neolithic societies. Their origin and function are regarded as indicators of social development.[1] A religious movement was suspected early on to be behind the megalith complexes.[2] This divided over the course of more than 8,000 years into various sects.[3]

The characteristics of the sites are determined regionally – for example, Bornholm only has passage graves – but was primarily resource-independent. Structurally, all the essential elements are anticipated in the Breton megalithic tradition, which is about 500 years older, but contrary to earlier assumptions there is nothing to suggest an architectural influence.

Building worker theory

One explanation for the different forms - in addition to the basic requirement of the availability of resources and technical progress - is the building worker theory advocated by Friedrich Laux and Ewald Schuldt (1914-1987). According to Laux, there are different "building traditions" or "building schools" behind this pattern of distribution.[4]: "If you also find stone chambers in a very small geographical area that have matching building elements, e.g. threshold stones made in the same way, and in some cases are almost identical in size, then one is inclined to think of construction crews who moved around in the local region and carried out orders. Their work probably included the procurement of the selected building material as well as the processing of the boulders themselves." And since the construction of such chambers with their inwardly inclined wall stones requires a certain knowledge of statics, one can always assume there would be a responsible master builder who would be in charge. On the basis of their technical construction, Ewald Schuldt concluded as early as 1972 that the monuments were executed under "the guidance of a specialist or groups of specialists".[5] Evidence of this is e.g. Sk 49 Skabersjö dolmen sn RAÄ 3, a dolmen in Schonen with a triangular enclosure, typical of Poland but entirely atypical of Scandinavia. In addition, there were and are regionalist approaches that assume an independent development of megalithic construction in the European areas, whereby one does not exclude the other.

Elements

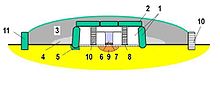

Schuldt divided the architectural elements into:

- Chamber structure (Kammeraufbau) – wall and roof design

- Wall infill (Zwischenmauerwerk)

- Entrance and threshold stone (Zugang und Schwellenstein)

- Chamber flooring (Kammerdielen)

- Chamber layout (Kammereinrichtung)

- Mound, enclosure and guardian stones (Hügel, Einfassung und Wächtersteine)

Chamber design

Design variations

There is a considerable difference in chamber design between sites where the capstones are exclusively supported at three points and those where one or more capstones are supported at two points (forming a trilithon).[a] The glacial erratics selected for the walls and roofs, in addition to being the right size, had at least one relatively flat side. Sometimes these were made by splitting a stone, probably by means of heating and quenching. At the narrow end of great dolmens, slabs made of red sandstone were also used, instead of erratics, for walls and infill sections, usually filling in gaps between the supporting stones or orthostats.

The orthostats, which were only dug into the ground a little way in the phase after the simple dolmens, were given the necessary purchase on the ground by basal slabs (Standplatten) and stone wedges (Keilsteine). By slighting tilting them towards the interior and packing them on the outside with compressed clay or stones, the orthostats of the trilithons were given greater stability, whilst the supporting stones at places with three-point supported capstones were essentially placed vertically.

Corbelling

In Denmark, several sites have corbels (Überlieger), usually doubled, supporting the capstones. In one of the sites at Neu Gaarz and Lancken-Granitz in Mecklenburg it is partially double-corbelled. The Rævehøj of Dalby on the Danish island of Zealand has a three- to four-corbel design, where the inside height of the otherwise less than 1.75 metre high chamber reaches over 2.5 m in height. In Liepen (Mecklenburg) and at several other places it is corbelled in the area of the roughly 0.5 m projecting corbel block.

Capstones

The finished capstones rarely have a weight exceeding 20 tons. By contrast in the rest of the megalithic region, weights of over 100 tons occur (e.g. the Browneshill Dolmen in County Carlow in Ireland and the Dolmen de la Pierre Folle (150 tons) near Montguyon in the Charente in France).

Floor plan

The floor plan of chambers is rarely square, but may be slightly oval, polygonal, rectangular (also bulging), diamond-shaped or trapezoidal.

Infill

Whilst the sidestones at many smaller sites stand close together, the infilled gaps (Zwischenmauerwerk) between orthostats of great dolmens and passage graves are more than one metre wide. On Zealand the chamber of a passage grave on Dysselodden is quite the reverse. Here, the orthostats, which are above the height of a man, are so precisely matched that a sheet of paper cannot be inserted in the cracks between them.

Entrances

Flooring, underfloor area

Floor coverings were obligatory in all chambers and were usually separated by the threshold stone (Schwellenstein) from the, usually uncobbled, entrance passage. The ante-chamber of great dolmens was usually left bare. In several cases the passages were also covered. In these cases, the original chamber was sometimes enhanced by a second threshold stone nearer the entrance.

The floor material varies tremendously from placed to place, but often consists of carefully laid cobbles over which a coat of clay was applied. In addition to red sandstone, in the form of grus and slabs, flint, flint grus, clay alone, gravel, or gneiss and slate slabs were occasionally used. Sites also occur where pieces of broken pottery or combinations of several materials are used. The thickness of the floor covering varies from three to ten centimetres. The floor at Sassen, Germany in Mecklenburg is unique. Here, thin red sandstone slabs have been placed vertically and not covered with a clay layer. The flooring apparently formed the final stage of building. How important floor coverings were, is demonstrated by the fact that subsequent users neither removed nor replaced them, nor did they cover them with a further layer. Floor coverings were especially in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Sweden also divided into sections (Quartiere).

Rooms or sections

Use of fire

According to E. Schuldt, the chambers were thoroughly cleaned when they were removed and fire was kindled in them.[citation needed] Singular fire and scorch marks on the bones indicate, however, that fires were burned during the successive occupation of these structures and not just in the process of their consecration or removal.[citation needed] 17 of the 106 sites investigated by Schuldt had glowing red floors.[citation needed]

Mound and enclosure

The Neolithic mound over the megalithic site was usually made of earth. Its material always came from the immediate neighbourhood and was often interspersed with stones. Pebble mounds (Rollsteinhugel) are those covered with a layer of pebbles. Such coverage was detected in Mecklenburg at about 50% of the sites studied, a few (Serrahn (Kuchelmiß) and Wilsen) still have their complete pebble layer.

In Cuxhaven county, there are megalithic sites covered by peat that have come to light today thanks to the lowering of the water table. These megaliths have no mound covering them. They are considered by some researchers as evidence that not all megalithic chambers were covered over. At these sites, however, it is unclear whether the mound fell a victim to erosion very soon after it had been made.

The long rectangular enclosure of the mound, with more or less large boundary stones, is widespread in Nordic megalith architecture. It is called a stone enclosure in English, a Huenenbett ("giant's bed") in German and a hunebed in Dutch. There are also circular, D-shaped (Lübeck-Blankensee, Gowens/Plön) and trapezoidal enclosures, of which 17 (with five different types of chambers) have been excavated in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The geometry of the enclosure is independent of the type or shape of the chamber that they surround. The dolmens or passage graves lying within stone enclosures may be rectangular, trapezoidal or somewhat oval in shape. The chambers in the enclosures can be oriented longitudinally (mostly in enclosures with simple dolmens) or transversely (transverse chambers - mostly in megaliths with passages) within the mounds. One example is the megaliths of Grundoldendorf, in the municipality of Apensen, in the county of Stade. There are also cases where several dolmens and passage graves lie within one enclosure (Ellested on Fyn (5), Waabs at Eckernförde (3). There are also different types of chamber in the same enclosure. In Idstedt a chamber was found in a round mound of 10 m diameter, which in turn was the starting point for the expansion of the megalith into an enclosure, only traces of which were left, however.

Dimensions

The enclosures can surrounded the actual mound very closely on all sides or, for example, can be 168 metres long and 4–5 metres wide surrounding a small simple dolmen (Lindeskov on Funen). Lindeskov is the second longest stone enclosure in Denmark (after the Kardyb Dysse between Tastum and Kobberup - 185 metres long). These extraordinary lengths occur as early as the pre-megalithic monuments of the Funnelbeaker culture. For example, one of the sites (No. 86) at Březno (German: Briesen) in North Bohemian Louny (German: Laun) a system of the "Niedźwiedź type" (NTT), at least 143.5 m long, even though the exact location of one end of it is indeterminable.

For comparison, the longest German barrow is located in the Sachsenwald forest in Schleswig-Holstein and measures 154 metres long.[b] The Visbeker Braut ("bride of Visbeck") is 104 metres long, the longest barrow in Lower Saxony. In Poland, the longest enclosure is an unchambered long barrow (kammerloses Hünenbett), 130 metres long. A 125-metre-long enclosure, also for an enclosure without a chamber is the longest in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Only 47 metres long, is the one at Steinfeld, the longest in Saxony-Anhalt. Westphalian gallery graves also classified as belonging to the Northern Megalithic Architecture, because they were also built by members of the Funnelbeaker culture, and are even shorter (maximum 35 metres). Sites with a single round enclosure for dolmens (Runddysse sacrifice stone, Poskær Stenhus or Runddysse of Vielsted) are smaller and rarely reach 20 metres in diameter.

See also

Notes

- ^ In the case of the Hohe Steinen in Wildeshausen, the ends and the middle were installed as three-point supports, the eight stones in between in two-point supports.

- ^ Often a barrow in Albersdorf, Holstein, is cited as the longest in Germany, at 160 metres. This is based on a typographical error in Ernst Sprockhoff's Atlas of Megalithic Germany - Schleswig-Hostein. The barrow is actually only 60 metres long, and is recorded as such in the State Register as LA53.

References

- ^ a b Müller (2009), p. 15.

- ^ Johann Karl Wächter: Statistics of the existing pagan monuments in the Kingdom of Hanover p. 9

- ^ Childe (1947), p. 46.

- ^ Laux, Friedrich (1979) Die Großsteingräber im nördlichen Niedersachsen. In: Heinz Schirnig (ed.): Großsteingräber in Niedersachsen (= Veröffentlichungen der Urgeschichtlichen Sammlungen des Landesmuseums zu Hannover. 24). Lax, Hildesheim, ISBN 3-7848-1224-4, pp. 59–90

- ^ Schuldt & Gehl (1972), p. 106.

Literature

- Probleme der Megalithgräberforschung [Entries on the 100th anniversary of Vera Leisner]. New York: de Gruyter. 1990. ISBN 3-11-011966-8. (Madrider Forschungen 16).

- Childe, Vere Gordon (1947). History. London: Cobbett Press.

- Müller, Johannes (2009). Neolithische Monumente und neolithische Gesellschaften. Varia Neolithica VI (in German). Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran, Archäologische Fachliteratur. pp. 7–16.

- Rzepecki, Seweryn (2011). The roots of megalithism in the TRB culture. Łódź: Instytut Archeologii Uniwersitetu Łódzkiego. ISBN 978-83-933586-1-8.

- Schuldt, Ewald; Gehl, Otto (1972). Die mecklenburgischen Megalithgräber: Untersuchungen zu ihrer Architektur und Funktion (in German). Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Sprockhoff, Ernst (1975). Atlas der Megalithgräber, Part 3. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag. ISBN 3-7749-1326-9.

- Sprockhoff, Ernst (1938). Die nordische Megalithkultur. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. (Handbuch der Urgeschichte Deutschlands 3).

- Strömberg, Märta (1971). Die Megalithgräber von Hagestad: Zur Problematik von Grabbauten und Grabriten. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 3-7749-0195-3. (Acta Archaeologica Lundensia. Series in 8°. No. 9).

- Walkowitz, Jürgen E. (2003). Das Megalithsyndrom: Europäische Kultplätze der Steinzeit (in German). Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran. ISBN 3-930036-70-3.

- Zich, B. (1999). "Vom Tumulus zum Langbett". Archäologie in Deutschland (in German). 3: 52.