The California Reich

| The California Reich | |

|---|---|

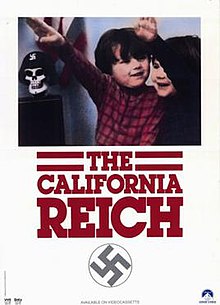

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Keith F. Critchlow Walter F. Parkes |

| Produced by | Keith Critchlow Walter F. Parkes[1] |

| Edited by | Keith Critchlow Walter F. Parkes |

| Music by | Craig Safan |

| Distributed by | City Life Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 55 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The California Reich was a 1975 documentary film on a group of neo-Nazis in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Tracy, California, USA. They were members of the National Socialist White People's Party, another name for the American Nazi Party that was started by George Lincoln Rockwell. It was screened at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival, but wasn't entered into the main competition.[2] It was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[3]

The film featured scenes with Jewish Defense League (JDL) leader Irv Rubin confronting American neo-Nazis.

The documentary was "unofficially sanctioned by the Nazis and The Jewish Anti-Defamation League finds it too mild in its condemnation."[4]

Production

According to a report in The New York Times the journalist, John J. O'Connor, the two filmmakers "Spent more than a year with the neo-Nazis before cameras were allowed to record families and rituals."[5] The filmmakers were quoted in the same article that they "Wanted to show the Nazis as members of our society, not as human monsters, but the people next door."[5]

The documentary borrows its style from the French film movement Cinema Vérité where narration was absent through the film and they let the subjects speak for themselves.[5]

Reception and legacy

In his 1978 report John J. O'Connor said the filmmakers "Succeed all too well as their working-class subjects become grotesque parodies of disturbing elements that can be detected in varying degrees at all levels of society." in response to their goal to not portray the communities as monsters. He also said that the "most poignant episodes involves a 10 year old boy who says he does not share his father's philosophy. He goes to youth meetings to please his dad."[5] In Saturday Review, Judith Crist called the film "a cool, intense, unsensational, and ultimately terrifying study." Crist continues by saying "There is no voice-over. The American Nazis speak for themselves. They are not frightening or funny. They are utterly ordinary and thereby terrifying."[6]

In Film Quarterly, Mitch Tuchman state that "the material is inherently interesting as a bit of American ethnography", but continued that Parkes and Crichlow have "a horrible ambivalence toward their subjects".[4]

The opening of this film shows NSWPP member Arnie Anderson recording a racist outgoing message on the party's phone machine. Later, the film shows a gathering of Nazis giving a Pledge of Allegiance to Adolf Hitler. Portions from both of these were used in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers as the speech given by the leader of the "American Socialist White People's Party" during a rally in a Chicago park, as he taunts angry counter-protesters.

See also

References

- ^ The Man Who Skied Down Everest Wins Documentary Feature: 1976 Oscars

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The California Reich". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ^ 1976|Oscars.org

- ^ a b Tuchman, Mitch (1977-07-01). "Review: California Reich". Film Quarterly. 30 (4): 37. doi:10.2307/1211583. ISSN 0015-1386. JSTOR 1211583. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ a b c d O'Connor, John J. (1978-12-12). "TV: 'California Reich' Visits West Coast Nazis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-08-20.

- ^ Crist, Judith (1976-10-16). "Some Bitter Tea for the Human Race". Saturday Review. Vol. 4, no. 2. pp. 42–43.

External links

- 1975 films

- American documentary films

- Documentary films about racism in the United States

- 1975 documentary films

- Neo-Nazi organizations in the United States

- Films shot in California

- White nationalism in California

- Films produced by Walter F. Parkes

- Films directed by Walter F. Parkes

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films