Beast of Gévaudan

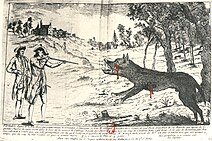

Artist's conception of one of the Beasts of Gévaudan, 18th-century engraving by A.F. of Alençon | |

| First attested | 1764 |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | La bête du Gévaudan (French) La Bèstia de Gavaudan (Occitan) |

| Country | France |

| Region | Gévaudan (modern-day Lozère and part of Haute-Loire) |

The Beast of Gévaudan (Template:Lang-fr, IPA: [la bɛt dy ʒevodɑ̃]; Template:Lang-oc) is the historic name associated with a man-eating animal or animals that terrorised the former province of Gévaudan (consisting of the modern-day department of Lozère and part of Haute-Loire), in the Margeride Mountains of south-central France between 1764 and 1767.[1]

The attacks, which covered an area spanning 90 by 80 kilometres (56 by 50 mi), were said to have been committed by one or more beasts of a tawny/russet color with dark streaks/stripes and a dark stripe down its back, a tail "longer than a wolf's" ending in a tuft according to contemporary eyewitnesses. It was said to attack with formidable teeth and claws, and appeared to be the size of a calf or cow and seemed to fly or bound across fields towards its victims. These descriptions from the period could identify the beast as a young lion, a striped hyena, a large wolf, a large dog, or a wolfdog, though its identity is still the subject of debate.

The Kingdom of France used a considerable amount of wealth and manpower to hunt the animals responsible, including the resources of several nobles, soldiers, royal huntsmen, and civilians.[1] The number of victims differs according to the source. A 1987 study estimated there had been 210 attacks, resulting in 113 deaths and 49 injuries; 98 of the victims killed were partly eaten.[1] Other sources claim the animal or animals killed between 60 and 100 adults and children and injured more than 30.[1] Victims were often killed by having their throats torn out. The beast was reported killed several times before the attacks finally stopped.

History

Beginnings

The Beast of Gévaudan committed its first recorded attack in the early summer of 1764. A young woman, who was tending cattle in the Mercoire Forest near the town of Langogne in the eastern part of Gévaudan, saw a beast "like a wolf, yet not a wolf" come at her.[2] However, the bulls in the herd charged the beast, keeping it at bay. They then drove it off after it attacked a second time. Shortly afterwards, on 30 June, the beast's first official victim was recorded: 14-year-old Jeanne Boulet was killed near the village of Les Hubacs near Langogne.[3] On 1 July, this victim was buried "without sacraments" because she could not confess before her death. However, the burial certificate specifies that she was killed by "the ferocious beast" (French: la bette [sic] féroce), which suggests that she is not the first victim but only the first declared.[4] A second victim was reported on 8 August. Aged 14, she lived in the hamlet of Masméjean, in the parish of Puy-Laurent. These two victims were killed in the Allier valley.

From the end of August and in September, other victims were recorded in the Mercoire Forest or its surroundings.[5] Throughout the remainder of 1764, more attacks were reported in the region. Very soon, terror gripped the populace because the beast was repeatedly preying on lone men, women, and children as they tended livestock in the forests around Gévaudan.[3] Reports note that the beast seemed only to target the victim's head or neck regions. Some witnesses claimed the beast had supernatural abilities. They believed it could walk on its hind legs and feet like humans. They believed the beast performed astounding leaps. They also believed the beast could repel bullets and come back from the dead after being struck and wounded.[6]

Increased attention

By late December 1764, rumors had begun circulating that there might be a pair of animals behind the killings. This was because there had been such a high number of attacks in such a short space of time and because many of the attacks appeared to have occurred or were reported nearly simultaneously. Some contemporary accounts suggest the creature was seen with another such animal, while others report that the beast was accompanied by its young.[8]

On 31 December, the Bishop of Mende Gabriel-Florent de Choiseul-Beaupré, also Count of Gévaudan, called for prayers and penance. This appeal has remained in history under the name of "commandment of the Bishop of Mende".[9] All the priests of the diocese had to announce it to their faithful. In this long text, the bishop described the beast as a scourge sent by God to punish men for their sins.[10] He quoted Saint Augustine in evoking the "justice of God", as well as the Bible and the divine threats uttered by Moses: "I will arm the teeth of wild beasts against them". Following this commandment prayers of Forty Hours' Devotion were observed for three consecutive Sundays.

In spite of these divine pleas, the massacre continued. On 12 January 1765, Jacques Portefaix and seven children from the village of Villaret, in the parish of Chanaleilles, were attacked by the beast. After several attacks, they drove it away by staying grouped together. The encounter eventually came to the attention of King Louis XV, who awarded 300 livres to Portefaix and another 350 livres to be shared among his companions. The king also rewarded Portefaix with an education at the state's expense. He then decreed that the French state would help find and kill the beast.[3] On 11 February, in the parish of Le Malzieu, was buried a little girl "about twelve years old who had been partly devoured on the present day by a man-eating beast that has been ravaging this country for nearly three months".[11]

By April 1765, the story of the beast had spread throughout Europe. The Courrier d'Avignon and English journalists made fun of the impotence of royal power in the face of a simple animal.[12][13] Meanwhile, the local bishop and the intendants had to deal with an influx of mail; people from all over France suggesting more or less eccentric methods to overcome the beast.[14] The court also issued depictions of the beast in Gévaudan so that "everyone [was] less terrified at his approach and less likely to be mistaken" and so that the packs of hunting dogs could be trained to chase the beast thanks to an effigy "executed in cardboard".[15][16][17]

Royal intervention

First Captain Duhamel of the Clermont Prince dragoons and his troops were soon sent to Gévaudan. Although extremely zealous in his efforts, non-cooperation on the part of the local herders and farmers stalled Duhamel's efforts. On several occasions he almost shot the beast, but was hampered by the incompetence of his guards. When the village of Le Malzieu was not present and ready as the beast crossed the Truyère river, Duhamel became frustrated.

When Louis XV agreed to send two professional wolf hunters, Jean Charles Marc Antoine Vaumesle d'Enneval and his son Jean-François, Captain Duhamel was forced to stand down and return to his headquarters in Clermont-Ferrand. Cooperating with d'Enneval was impossible as the two differed too much in their strategies; Duhamel organised wolf hunting parties while d'Enneval and his son believed the beast could only be shot using stealthy techniques. Father and son D'Enneval arrived in Clermont-Ferrand on 17 February 1765, bringing eight bloodhounds that had been trained in wolf hunting. Over the next four months, the pair hunted for Eurasian wolves, believing that one or more of these animals was the beast. However, when the attacks continued, the D'Ennevals were replaced in June 1765 by François Antoine (sometimes wrongly identified with his son, Antoine de Beauterne), the king's sole arquebus bearer and lieutenant of the Hunt, who arrived in Le Malzieu on 22 June.[18]

On 11 August, Antoine organised a great hunt. That day saw the feat of the "Maid of Gévaudan". Marie-Jeanne Vallet, about 20 years old, was the servant of the parish priest of Paulhac. In the company of other peasant women, she was taking a footbridge to cross a small stream when the beast appeared. The women took a few steps back but the beast threw itself on Marie-Jeanne. The latter managed to plant her spear into its chest. The beast dropped into the river and disappeared into the woods.[19] The story quickly reached Antoine, who went to the scene. He found that the spear was indeed covered in blood and that the traces found were similar to those of the beast. In a letter to Saint-Florentin, Minister of the King's House, comparing Marie-Jeanne to Joan of Arc, he nicknamed her the "Maid of Gévaudan".[20]

On 20 or 21 September, Antoine killed a large grey wolf measuring 80 cm (31 in) high, 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) long and weighing 60 kg (130 lb). The wolf, which was named Le Loup de Chazes after the nearby Abbaye des Chazes, was said to have been quite large for a wolf. Antoine officially stated: "We declare by the present report signed from our hand, we never saw a big wolf that could be compared to this one. Hence, we believe this could be the fearsome beast that caused so much damage." The animal was further identified as the culprit by several attack survivors, who recognised the scars on its body inflicted by victims defending themselves.[1] Among them were Marie-Jeanne Vallet and her sister.[23]

After the report was written, François Antoine's son loaded the animal onto his horse and set off for Paris. At Saint-Flour, he showed it to Monsieur de Montluc. In Clermont-Ferrand, he had it stuffed.[24] He left Clermont on 27 September and arrived at Versailles on 1 October, where he was hailed as a hero. The beast was exhibited in the Jardins du Roi. Meanwhile, François Antoine and his gamekeepers stayed in the Auvergne woods to chase down the beast's female partner and her two grown pups, which had been reported near the Abbey of Chazes. On 19 October, Antoine succeeded in killing the female wolf and a pup, which seemed already larger than its mother. At the examination of the pup, it appeared to have a double set of dewclaws, a hereditary malformation found in the Bas-Rouge or Beauceron dog breed.[25] The other pup was shot and hit and was believed to have died while retreating between the rocks.[8] Antoine returned to Paris on 3 November and received a large sum of money (over 9,000 livres) as well as fame, titles, and awards.

Final attacks

The month of November passed without any attack being reported. The populace dared to believe that Antoine had indeed killed the beast. In a letter from 26 November, the syndic Étienne Lafont affirmed to the intendant of Languedoc: "We no longer hear of anything relating to the beast".[26] But quickly, rumors spread of new attacks, towards Saugues and Lorcières. On 2 December, two boys aged 6 and 12 were further attacked, suggesting that the beast was still alive. The beast tried to capture the youngest, but it was successfully fought off by the older boy. Soon after, successful attacks followed and some of the shepherds witnessed that the beast showed no fear around cattle at all.[27] A dozen more deaths are reported to have followed attacks near La Besseyre-Saint-Mary.[citation needed]

Until the beginning of 1766, these facts remained episodic and no one knew if they were attributable to the beast or to wolves. However, in a letter he wrote to the intendant of Auvergne on 1 January 1766, Monsieur de Montluc seemed convinced that the beast had indeed reappeared.[28] The intendant alerted the king, but Louis XV no longer wanted to hear about a ferocious beast that his arquebus bearer had overcome. From then on, newspapers no longer reported any of the attacks that occurred in Gévaudan or in the south of Auvergne.

In March 1766, the attacks multiplied. The local gentlemen now knew that their salvation would not come from the court. On 24 March, the Particular Estates of Gévaudan were held at Marvejols. Étienne Lafont and the young Marquis d'Apcher, a local nobleman, recommend poisoning the corpses of dogs and carrying them to the usual passages of the beast.[28] But the latter did not seem to cover as much ground as before; it settled in the Trois Monts region—Mont Mouchet, Mont Grand and Montchauvet—about 15 km (9.3 mi) apart.

The measures taken proved ineffective. Small hunts were organised in vain. The beast continued its attacks throughout 1766. But its mode of operation had changed: it seemed less enterprising and much more cautious, as revealed by various correspondence, including that of Canon Ollier, parish priest of Lorcières, to Étienne Lafont.[29]

At the beginning of 1767, the attacks experienced a slight lull,[30] but they resumed in the spring. The populace no longer knew what to do, except to pray. Pilgrimages were increasing, mainly to Notre-Dame-de-Beaulieu[b] and Notre-Dame-d'Estours.[c] On 18 June, it was reported to the Marquis d'Apcher that the beast had been seen the day before in the parishes of Nozeyrolles and Desges. In the latter, in the village of Lesbinières, it allegedly killed 19-year-old Jeanne Bastide.[5]

Killing by Jean Chastel

The killing of the creature that eventually marked the end of the attacks is credited to a local hunter named Jean Chastel, who shot it at the slopes of Mont Mouchet (now called la Sogne d'Auvers) during a hunt organised by the Marquis d'Apchier on 19 June 1767.[3] In 1889, Abbot Pourcher told the edifying oral tradition which said that the pious hero Chastel shot the creature after reciting his prayers but the historical accounts do not report any such thing.[31][32][33][34] The story about the large-caliber bullets, home-made with Virgin Mary's medals, is a literary invention by the French writer Henri Pourrat.[35]

The body was then loaded onto a horse and brought to the Château de Besque of the Marquis d'Apchier, located in Charraix, where it was necropsied by Dr. Boulanger, a surgeon at Saugues.[36][37] Dr. Boulanger's post-mortem report was transcribed by the royal notary Roch Étienne Marin and is known as the "Marin Report" on the beast;[38][39] the results of the examination were consistent with a large wolf or wolf-dog, but the remains were incomplete by the time Boulanger acquired them, precluding conclusive identification of the animal.[37] The beast was then exhibited at the château, where the Marquis d'Apcher lavishly received crowds, which thronged to see the remains. Numerous testimonies from victims of attacks enriched the Marin Report. The beast stayed in Besque for a dozen days.[40]

Fate of the remains

The Marquis d'Apcher instructed a servant named Gibert to take the beast to Versailles to show it to the king. According to an oral tradition reported by Abbot Pourcher[41] and repeated by several authors,[42][43] Jean Chastel would have been on the trip, but Louis XV would have disdainfully rejected him because the remains, summarily stuffed by an apothecary who had contented himself with replacing the entrails with straw, gave off a stench that the heat made even more unbearable. However, this version is called into question by the testimony of the servant of the Marquis d'Apcher, collected in 1809:

Gibert finally arrived in Paris, went to stay at the hôtel particulier of Mr. de la Rochefoucault to whom he at the same time gave a letter in which Mr. d'Apchier begged the lord to inform the king of the happy deliverance of the monster (...) The king was at Compiègne at the time and, according to the news he was told, he gave orders to Mr. de Buffonto to visit and examine this animal. This naturalist, in spite of the dilapidation to which the worms had reduced it and the fall of all the hairs, following the heat of the end of July and the beginning of August, in spite of still the bad odor which it gave off, after a serious examination, judged that it was only a big wolf (...) As soon as Mr. de Buffon had made the examination of this animal, Gibert hastened to have it buried because of its great stench and he said he had been so inconvenienced by it that he was sick and bedridden for more than 15 days in Paris. He suffered from this disease for more than 6 years and he even attributed to this bad smell that he breathed for so long the poor health he has always been burdened with since that time.[44]

It emerges that Jean Chastel did not accompany Gibert to Paris. Likewise, the servant never presented the remains of the beast to the court of Louis XV. Finally, Buffon left no document on this subject. Neither kept in the collections of the Jardin du Roi in Paris, nor buried in Marly or Versailles, the beast was probably buried in the garden of the private mansion of Louis Alexandre de La Rochefoucauld, a gentleman sharing a distant common ancestor with the Marquis of Apcher. The hotel of La Rochefoucauld, located on the Rue de Seine, would be demolished in 1825.[45]

The attacks in Gévaudan ceased definitively. The authorities of the diocese granted rewards to the hunters: Jean Chastel received 72 livres on 9 September; Jean Terrisse received 78 livres on 17 September; the hunters who accompanied them shared 312 livres on 3 May 1768.[46]

Description

Morphology

Various questions about the nature of the Beast of Gévaudan have aroused interest and contributed to the enthusiasm for its history. Descriptions of the time vary, and reports may have been greatly exaggerated, owing to public hysteria. In terms of morphology, although none of the killed animals have been preserved, the beast was generally described as a wolf-like canine with a tall, lean frame capable of taking great strides. It was said to be the size of a calf, a cow, or, in some cases, a horse.[2] It had an elongated head similar to that of a greyhound, with a flattened snout, pointed ears, and a wide mouth sitting atop a broad chest. The beast's tail was also reported to have been notably longer than a wolf's, with a prominent tuft at the end. The beast's fur was described as tawny or russet in color but its back was streaked with black, and a white heart-shaped pattern was noted on its underbelly.[47]

Behaviour

Several tales spoke of the beast's invulnerability. Indeed, hit by the bullets of reputedly skilled shooters, the beast would have risen each time. Testimonies attributed to the beast a gift of ubiquity. In a very short interval of time, it would have been seen in places several kilometres away. However, in many cases, these distances could be covered by a single animal. Two of the beast's most singular traits were its familiarity and his boldness. At least until François Antoine's departure, it did not seem to fear man. When it encountered resistance, it would move "40 paces" away, sometimes sitting on its hindquarters for a few moments and, if not pursued, would come back to the charge. Then it would move away at a walk or a short trot. Several victims were attacked in the middle of villages[e] and most of the testimonies related to attacks during the day.[49] Finally, by showing a relentlessness that did not always seem dictated by hunger,[50] the beast showed an astonishing aggressiveness. In addition, its unusual agility allowed it to jump over walls that a dog could not cross.

The "Marin Report"

On 20 June 1767, the day after the death of the animal killed by Jean Chastel, the royal notary Roch Étienne Marin wrote an autopsy report at the Marquis d'Apcher's Château de Besque in Charraix. Preserved in the French National Archives, this memoir was discovered in 1952 by the historian Élise Seguin.[51] It provides precise information on "This animal which seemed to us to be a wolf; But extraordinary and very different by its figure and its proportions from the wolves that one sees in this country."[38][39]

The report also details the dental formula. The upper jaw consists of 20 teeth: 6 incisors, 2 canines and 12 molars; the lower jaw has 22: 6 incisors, 2 canines and 14 molars. This likely points to a canid. The document also describes the animal's wounds and scars. Finally, it includes the testimonies of several people who recognised it.[39]

- Report of the examination of the animal's body addressed to the intendant of Auvergne on 20 June 1767. French National Archives, AE/II/2927.

Hypotheses

According to modern scholars, public hysteria at the time of the attacks contributed to widespread myths that supernatural beasts roamed Gévaudan, but deaths attributed to a beast were more likely the work of a number of wolves or packs of wolves.[52][53]

Attacks by wolves were a very serious problem during the era, not only in France but throughout Europe, with thousands of deaths attributed to wolves in the 18th century alone.[54] In the spring of 1765, in the midst of the Gévaudan hysteria, an unrelated series of attacks occurred near the commune of Soissons, northeast of Paris, when an individual wolf killed at least four people over a period of two days before being tracked and killed by a man armed with a pitchfork.[55] Such incidents were fairly typical in rural parts of both Western Europe and Central Europe.[citation needed]

The Marin Report describes the creature as a wolf of unusually large proportions: "This animal which seemed to us to be a wolf; But extraordinary and very different by its figure and its proportions from the wolves that one sees in this country. This is what we have certified by more than three hundred people from all around who came to see it."[38][39]

Despite the widely held interpretation based on most of the historical research that the beast was a wolf[56][57] or another wild canid, several alternative theories have been proposed; some think a lion (namely a subadult male) escaped from a menagerie, due to the size and some descriptions being more similar to a lion than a wolf. Others consider an escaped striped hyena, due to some sketches of the beast describing it as such. Another theory is that a large feral dog or wolfdog was responsible, since some sightings were of an animal that looked similar to a wolf, but was not one.[58][59] In a 2021 talk by François-Louis Pelissier, based on the described appearance of the animal and specific details of behaviour and what can be inferred about historical distribution, he argued that beast encounters could most likely be blamed on the Italian wolf Canis lupus italicus.[60]

In popular culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

Literature

- Nicolas-Edme Rétif de la Bretonne's 1781 novel La Découverte australe mentions "la Bête-du-Gévaudan" in passing[61]

- The earliest known literary reference to the Beast of Gévaudan occurs in Élie Berthet's 1858 novel La Bête du Gévaudan (translated as "The Beast of Gevaudan", but not currently available in English), in which the killings are attributed to both a wolf and a man who believes himself to be a werewolf

- In 1904, the author and journalist Robert Sherard reworked Berthet's idea in his novel Wolves: An Old Story Retold, which once again featured both a werewolf and a huge savage wolf. Élie Berthet's La Bête du Gévaudan is mentioned in the introduction as being the source of the story

- Robert Louis Stevenson traveled through the region in 1878 and described the incident in his book Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, in which he claims that at least one of the creatures was a wolf:

For this was the land of the ever-memorable Beast, the Napoleon Bonaparte of wolves. What a career was his! He lived ten months at free quarters in Gévaudan and Vivarais; he ate women and children and "shepherdesses celebrated for their beauty"; he pursued armed horsemen; he has been seen at broad noonday chasing a post-chaise and outrider along the king's high-road, and chaise and outrider fleeing before him at the gallop. He was placarded like a political offender, and ten thousand francs were offered for his head. And yet, when he was shot and sent to Versailles, behold! a common wolf, and even small for that.

— Chapter: "I Have a Goad"

- In the Patricia Briggs novel Hunting Ground, the beast is in fact Jean Chastel, who is a werewolf

- In the Jim Butcher novel Fool Moon, part of The Dresden Files, the beast is mentioned as an example of a particularly powerful and vicious type of werewolf known as a loup-garou (the French phrase for a werewolf), with the curse being hereditary. Chastel's claim of using silver bullets is also referred to as the sole weakness of the loup-garou – bullets made of inherited silver

- In the Jun Mochizuki manga series The Case Study of Vanitas, the Beast of Gévaudan and events surrounding it are fictionalized to fit the work's world

- My Hero Academia features a student, Jurota Shishida, whose power "Beast" allows him to enlarge himself and gain animalistic features. His hero name, Gevaudan, is directly taken from the creature

- Dropkick on My Devil! features one of the main characters keeping a beast of Gévaudan as a pet

- In the 2019 R. J. Palacio graphic novel White Bird, the main character has nightmares about a fearsome wolf during her time in hiding during the Holocaust; the wolf later kills her former schoolmate, Vincent, who is working with the Nazis and has discovered her hiding place. The author notes in the book's glossary that "My inspiration for the wolf of Sara's nightmares came from the stories of the Beast of Gevaudan."

Film and television

- Walerian Borowczyk's film La Bête (1975) includes a dream sequence featuring an erotic encounter with an indeterminate creature. This sequence was originally included as a segment of his earlier portmanteau film Contes immoraux (1974) under the title La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan.[citation needed]

- The beast is featured in an episode of Animal X, which suggested it was a wolf-dog hybrid that was trained to attack people.[citation needed]

- Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001),[62] directed by Christophe Gans, is an action film based on the legend. In the film, the Beast is a lion dressed up in armor to mask its identity.

- The French television film La bête du Gévaudan (2003),[63] directed by Patrick Volson, was based on the attacks of the beast.

- In October 2009, the History Channel aired a documentary, The Real Wolfman, which argues that the beast was an exotic animal, a striped hyena, a long-haired species of hyena now extinct in Europe and the likely possibility that its killer, Jean Chastel, was also the one who trained the animal in the first place, using it as a means to get back into the good graces of the Church. History also talked about the Beast in The UnXplained, featuring theories about what the animal/s could be.[64]

- In the 2010 remake The Wolfman, the wolf-headed cane given to Lawrence Talbot was (according to the previous owner) acquired in the city of Gévaudan.[citation needed]

- In the MTV drama Teen Wolf, the character Allison learns in the sixth episode of the first season that her werewolf-hunting family was responsible for slaughtering the Beast of Gévaudan. The same beast is the main focus of the second half of the series' fifth season and Crystal Reed returns as a special guest star to portray Allison's ancestor Marie Jeanne Valet, also known as, The Maid of Gévaudan .[65]

- The beast was featured in an episode of the podcast Lore entitled "Silver Lining".[66]

- Netflix will make a feature film produced by Blumhouse Productions.[67]

- The Cursed, a 2022 movie set in late-19th-century France, features the beast as a gypsy curse placed on a French village.[68]

Music

- In May 2021, the metal group Powerwolf released the song Beast of Gévaudan,[69] where the titular beast is portrayed as heroic and holy: "Beast of Gévaudan, for the wrath of God to come [...] Ascent like thunder to tear down the enemies of God". A French version of the song was released on 2 July 2021 and is now available on the 2023 album Interludium.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ The burial certificate reads:

The year 1764 and 1 July was buried Jeane Boulet without sacraments, having been killed by the ferocious beast present Joseph Vigi(er) and Jean Rebour.

- ^ Located in today's municipality of Paulhac-en-Margeride, Lozère

- ^ Located in today's municipality of Monistrol-d'Allier, Haute-Loire

- ^ The description reads:

Portrait of the Hyena, ferocious Beast that desolates the Gevaudan, seen by Mr. Duhamel Officer of the Dragoons volunteers of Clermont, detached to the pursuit of this dangerous animal.

- ^ According to Michel Louis, 22% of the victims were attacked in the middle of villages.[48]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e "The Fear of Wolves: A Review of Wolf Attacks on Humans" (PDF). Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ a b Williams, Joseph. "What was the Beast of Gévaudan". historyhannel.com. History Channel. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Boissoneault, Lorraine (26 June 2017). "When the Beast of Gévaudan Terrorized France". Smithsonian. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Archives départementales de l'Ardèche, commune de Saint-Étienne-de-Lugdares, Baptêmes, mariages et sépultures de 1757 à 1780 (in French), p. 113

- ^ a b Fabre, François (2006). "Appendix: table of victims of the Beast". La Bête du Gévaudan, édition complétée par Jean Richard (in French). Clermont-Ferrand: De Borée.

- ^ Nelson, January. "12 Facts About The Beast, Of Gevaudan, The Wolflike Creature Who Terrorized France". Thought Catalog. Thought Catalog. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Fabre, François (2006). "Table of illustrations". La Bête du Gévaudan, édition complétée par Jean Richard (in French). Clermont-Ferrand: De Borée.

- ^ a b Fabre 1930, p. 111–116.

- ^ Laurent Mourlat, La Bête du Gévaudan : l'animal pluriel (1764-1767) (in French), Mémoire de Master, Études européennes et américaines, filière France. Université d'Oslo, Institut de littérature, civilisation et langues européennes, 2016, p. 166–173

- ^ Pierre Pourcher, Histoire de la bête du Gévaudan, véritable fléau de Dieu (in French), Saint-Martin-de-Boubaux, Pierre Pourcher, 1889, chap. 10

- ^ "1 MI EC 090/4 - Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures - 1719-1772 Archives départementales de la Lozère". Archives départementales de la Lozère (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Fabre 1930, p. 55.

- ^ Moriceau 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Pierre Pourcher, Histoire de la bête du Gévaudan, véritable fléau de Dieu (in French), Saint-Martin-de-Boubaux, Pierre Pourcher, 1889, chap. 17

- ^ "C 44 - Traque de la bête du Gévaudan. C 44 - 1764-1785". Archives départementales de l'Hérault (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "C 44-1 - Estampe représentant la chasse de la bête du Gévaudan (avril 1765). C 44-1 - 1765". Archives départementales de l'Hérault (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "C 44-2 - Représentation de la bête du Gévaudan sous forme de hyène. C 44-2 - 1765". Archives départementales de l'Hérault (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Fabre 1930, p. 69.

- ^ Michel Louis, La Bête du Gévaudan (in French), edition 2006, part I, chapter 6

- ^ Buffière 1985, p. 1163.

- ^ Mazel & Garcin 2008, p. 48–49.

- ^ Mazel & Garcin 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Michel Louis, La Bête du Gévaudan (in French), edition 2006, part I, chapter 7

- ^ Michel Louis, La Bête du Gévaudan (in French), edition 2006, part I, chapter 7

- ^ "Beauceron Dog Breed Information". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Buffière 1985, p. 1167.

- ^ Bressan, David (28 June 2017). "How An Ancient Volcano Helped A Man-Eating Wolf Terrorize 18th Century France". Forbes. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ a b Michel Louis, La Bête du Gévaudan (in French), edition 2006, part I, chapter 8

- ^ Fabre 1930, p. 129–138.

- ^ Fabre 1930, p. 149.

- ^ Buffière 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Gibert 1993, p. 24–25; 64.

- ^ Crouzet 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Soulier 2016, p. 193–195.

- ^ Crouzet 2001, p. 156–158.

- ^ Buffière 1985, p. 1172.

- ^ a b "Hunting the Beast of Gevaudan". Skeptoid. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Moriceau 2008, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d "Le rapport Marin" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Fabre 1930, p. 157–158.

- ^ Favre 2017, p. 148.

- ^ Louis 2003, p. 178–179.

- ^ Moriceau 2008, p. 246.

- ^ Baud'huin & Bonet 2018, p. 208.

- ^ Baud'huin & Bonet 2018, p. 210–211.

- ^ Fabre 1930, p. 159–160.

- ^ Pourcher, Pierre (1889). Translated by Brockis, Derek The Beast of Gevaudan AuthorHokuse, 2006, p. 5 ISBN 978-1467014632

- ^ Michel Louis, La Bête du Gévaudan (in French), edition 2006

- ^ Michel Louis, La Bête du Gévaudan (in French), edition 2006, part II, chapter 2

- ^ Mazel & Garcin 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Laurent Mourlat, La Bête du Gévaudan : l'animal pluriel (1764-1767) (in French), Mémoire de Master, Études européennes et américaines, filière France. Université d'Oslo, Institut de littérature, civilisation et langues européennes, 2016, p. 153

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 367.

- ^ Smith 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Moriceau 2007, p. 463.

- ^ Rousseau 1765, p. 173.

- ^ Favre 2017, p. 159.

- ^ Chabrol 2018, p. 111.

- ^ Taake, Karl-Haans (27 September 2016). "Solving the Mystery of the 18th-Century Killer 'Beast of Gévaudan'". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Taake, Karl-Haans (February 2020). "Carnivore Attacks on Humans in Historic France and Germany: To Which Species Did the Attackers Belong?". ResearchGate.

- ^ "Cronch Cats, Beasts of Gévaudan, Dinosauroids, Mesozoic Art and Much More: TetZooMCon 2021 in Review". Tetrapod Zoology. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Nicolas-Edme Rétif de la Bretonne, La Découverte australe, ou Le Dédale français, vol. 1, p. 128, Leipzig, 1781.

- ^ Christophe Gans (Director) (2001). Le Pacte des Loups (Motion picture).

- ^ Patrick Volson (Director) (2003). La Bête du Gévaudan (Motion picture).

- ^ "The Real Wolfman". History Alive. Season 4. Episode 16. History. Archived from the original on 3 August 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ Massabrook, Nicole (24 February 2016). "'Teen Wolf' Season 5B Spoilers: Episode 19 Synopsis Released; What Will Happen In 'The Beast Of Beacon Hills'?". International Business Times. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Aaron Mahnke (16 October 2017). "Silver Lining". Lore (Podcast).

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (8 March 2021). "'Sons Of Anarchy's Kurt Sutter Makes Film Helming Debut On 'This Beast' For Blumhouse, Netflix". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "The Cursed [Original title: Eight for Silver]". IMDb.

- ^ "Beast of Gevaudan". YouTube (Podcast). 20 May 2021. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021.

Bibliography

- Baud'huin, Benoît; Bonet, Alain (2018). Gévaudan : petites histoires de la grande bête. Hors Temps (in French). Plombières-les-Bains: Ex Aequo Éditions. ISBN 978-2-37873-070-3.

- Buffière, Félix (1985). "Ce tant rude" Gévaudan (in French). Mende: Société des Lettres, Sciences et Arts de la Lozère.

- Buffière, Félix (1994). La bête du Gévaudan: une énigme de l'histoire (in French). Félix Buffière.

- Chabrol, Jean-Paul (2018). La bête des Cévennes et la bête du Gévaudan en 50 questions (in French). Alcide Éditions. ISBN 978-2-37591-028-3.

- Crouzet, Guy (2001). La grande peur du Gévaudan (in French). Guy Crouzet. ISBN 2-9516719-0-3.

- Fabre, François (1930). La Bête du Gévaudan (in French). Paris: Librairie Floury.

- Favre, Jean-Paul (2017). La Bête du Gévaudan: légende et réalité (in French). Debaisieux. ISBN 978-2-913381-96-4.

- Gibert, Jean-Marc (1993). La Bête du Gévaudan. Les auteurs du XVIIIe, XIXe, XXe siècle: historiens ou conteurs ? (in French). Société des Lettres, Sciences et Arts de la Lozère.

- Louis, Michel (2003). La bête du Gévaudan : l'innocence des loups. Tempus (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02054-X.

- Mazel, Éric; Garcin, Pierre-Yves (2008). La bête du Gévaudan à travers 250 ans d'images. Les musées de l'imaginaire (in French). Marseille: Gaussen. ISBN 978-2-35698-003-8.

- Moriceau, Jean-Marc (2007). Histoire du méchant loup : 3000 attaques sur l'homme en France (XVe–XXe siècle) (in French). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-62880-6.

- Moriceau, Jean-Marc (2008). La bête du Gévaudan : 1764-1767. L'histoire comme un roman (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-584173-5.

- Rousseau, Pierre (1765). Journal encyclopédique (in French). Bouillon: De l'Imprimerie du Journal.

- Smith, Jay M. (2011). Monsters of the Gévaudan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04716-7.

- Soulier, Bernard (2016). Sur les traces de la bête du Gévaudan et de ses victimes (in French). Éditions du Signe. ISBN 978-2-7468-2573-4.

- Thompson, Richard H. (1991). Wolf-Hunting in France in the Reign of Louis XV: The Beast of the Gévaudan. ISBN 0-88946-746-3.

External links

Media related to Beast of Gévaudan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Beast of Gévaudan at Wikimedia Commons- Robert Darnton, The Wolf Man's Revenge, The New York Review of Books, June 9, 2011; review of Monsters of the Gévaudan: The Making of a Beast by Jay M. Smith (Harvard University Press, 2011).

- Solving the Mystery of the 18th-Century Killer "Beast of Gévaudan" (National Geographic)

- Beast of Gévaudan web site (various languages)

- Dunning, Brian (16 June 2020). "Skeptoid #732: Hunting the Beast of Gevausan". Skeptoid.

- Beast of Gévaudan

- 1764 in France

- 1767 animal deaths

- Canid attacks

- Deaths due to wolf attacks

- Events of the Ancien Régime

- History of Occitania (administrative region)

- Lozère

- Occitania

- French folklore

- French legendary creatures

- Individual animals in France

- Individual wild animals

- Individual wolves

- Man-eaters

- Werewolves

- Gévaudan