André Malraux

Georges André Malraux | |

|---|---|

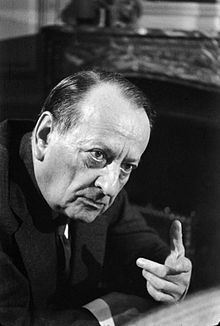

André Malraux in 1974 | |

| Born | Georges André Malraux 3 November 1901 Paris, France |

| Died | 23 November 1976 (aged 75) |

| Occupation | Author, statesman |

| Citizenship | French |

| Notable works | La Condition Humaine (Man's Fate) (1933) |

| Notable awards | Prix Goncourt |

| Spouse | Clara Goldschmidt, Marie-Madeleine Lioux |

| Partner | Josette Clotis, Louise de Vilmorin |

| Children | Florence, Pierre-Gauthier, Vincent, Lilya Maouchi (Le ting) |

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

Georges André Malraux DSO (/mælˈroʊ/ mal-ROH, French: [ɑ̃dʁe malʁo]; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and Minister of Cultural Affairs. Malraux's novel La Condition Humaine (Man's Fate) (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed by President Charles de Gaulle as Minister of Information (1945–46) and subsequently as France's first Minister of Cultural Affairs during de Gaulle's presidency (1959–1969).

Early years

Malraux was born in Paris in 1901, the son of Fernand-Georges Malraux (1875–1930) and Berthe Félicie Lamy (1877–1932). His parents separated in 1905 and eventually divorced. There are suggestions that Malraux's paternal grandfather committed suicide in 1909.[1]

Malraux was raised by his mother, maternal aunt Marie Lamy and maternal grandmother, Adrienne Lamy (née Romagna), who had a grocery store in the small town of Bondy.[1][2] His father, a stockbroker, committed suicide in 1930 after the international crash of the stock market and onset of the Great Depression.[3] From his childhood, associates noticed that André had marked nervousness and motor and vocal tics. The recent biographer Olivier Todd, who published a book on Malraux in 2005, suggests that he had Tourette syndrome, although that has not been confirmed.[4] Either way, most critics have not seen this as a significant factor in Malraux's life or literary works.

The young Malraux left formal education early, but he followed his curiosity through the booksellers and museums in Paris, and explored its rich libraries as well.

Career

Early years

Malraux's first published work, an article entitled "The Origins of Cubist Poetry", appeared in Florent Fels' magazine Action in 1920. This was followed in 1921 by three semi-surrealist tales, one of which, "Paper Moons", was illustrated by Fernand Léger. Malraux also frequented the Parisian artistic and literary milieux of the period, meeting figures such as Demetrios Galanis, Max Jacob, François Mauriac, Guy de Pourtalès, André Salmon, Jean Cocteau, Raymond Radiguet, Florent Fels, Pascal Pia, Marcel Arland, Edmond Jaloux, and Pierre Mac Orlan.[5] In 1922, Malraux married Clara Goldschmidt. Malraux and his first wife separated in 1938 but didn't divorce until 1947. His daughter from this marriage, Florence (b. 1933), married the filmmaker Alain Resnais.[6] By the age of twenty, Malraux was reading the work of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who was to remain a major influence on him for the rest of his life.[7] Malraux was especially impressed with Nietzsche's theory of a world in continuous turmoil and his statement "that the individual himself is still the most recent creation" who was completely responsible for all of his actions.[7] Most of all, Malraux embraced Nietzsche's theory of the Übermensch, the heroic, exalted man who would create great works of art and whose will would allow him to triumph over anything.[8]

Indochina

T. E. Lawrence, aka "Lawrence of Arabia", has a reputation in France as the man who was supposedly responsible for France's troubles in Syria in the 1920s. An exception was Malraux who regarded Lawrence as a role model, the intellectual-cum-man-of-action and the romantic, enigmatic hero.[9] Malraux often admitted to having a "certain fascination" with Lawrence, and it has been suggested that Malraux's sudden decision to abandon the Surrealist literary scene in Paris for adventure in the Far East was prompted by a desire to emulate Lawrence who began his career as an archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire excavating the ruins of the ancient city of Carchemish in the vilayet of Aleppo in what is now modern Syria.[10] As Lawrence had first made his reputation in the Near East digging up the ruins of an ancient civilization, it was only natural that Malraux should go to the Far East to likewise make his reputation in Asia digging up ancient ruins.[11] Lawrence considered himself a writer first and foremost while also presenting himself as a man of action, the Nietzschean hero who triumphs over both the environment and men through the force of his will, a persona that Malraux consciously imitated.[12] Malraux often wrote about Lawrence, whom he described admiringly as a man with a need for "the absolute", for whom no compromises were possible and for whom going all the way was the only way.[13] Along the same lines, Malraux argued that Lawrence should not be remembered mainly as a guerrilla leader in the Arab Revolt and the British liaison officer with the Emir Faisal, but rather as a romantic, lyrical writer as writing was Lawrence's first passion, which also described Malraux very well.[14] Although Malraux courted fame through his novels, poems and essays on art in combination with his adventures and political activism, he was an intensely shy and private man who kept to himself, maintaining a distance between himself and others.[15] Malraux's reticence led his first wife Clara to later say she barely knew him during their marriage.[15]

In 1923, aged 22, Malraux and Clara left for the French Protectorate of Cambodia.[16] Angkor Wat is a huge 12th century temple situated in the old capital of the Khmer empire. Angkor (Yasodharapura) was "the world's largest urban settlement" in the 11th and 12th centuries supported by an elaborate network of canals and roads across mainland Southeast Asia before decaying and falling into the jungle.[17] The discovery of the ruins of Angkor Wat by Westerners (the Khmers had never fully abandoned the temples of Angkor) in the jungle by the French explorer Henri Mouhot in 1861 had given Cambodia a romantic reputation in France, as the home of the vast, mysterious ruins of the Khmer empire. Upon reaching Cambodia, Malraux, Clara and friend Louis Chevasson undertook an expedition into unexplored areas of the former imperial settlements in search of hidden temples, hoping to find artifacts and items that could be sold to art collectors and museums. At about the same time archaeologists, with the approval of the French government, were removing large numbers of items from Angkor - many of which are now housed in the Guimet Museum in Paris. On his return, Malraux was arrested and charged by French colonial authorities for removing a bas-relief from the exquisite Banteay Srei temple. Malraux, who believed he had acted within the law as it then stood, contested the charges but was unsuccessful.[18]

Malraux's experiences in Indochina led him to become highly critical of the French colonial authorities there. In 1925, with Paul Monin,[19] a progressive lawyer, he helped to organize the Young Annam League and founded a newspaper L'Indochine to champion Vietnamese independence.[20] After falling foul of the French authorities, Malraux claimed to have crossed over to China where he was involved with the Kuomintang and their then allies, the Chinese Communists, in their struggle against the warlords in the Great Northern Expedition before they turned on each other in 1927, which marked the beginning of the Chinese Civil War that was to last on and off until 1949.[21] In fact, Malraux did not first visit China until 1931 and he did not see the bloody suppression of the Chinese Communists by the Kuomintang in 1927 first-hand as he often implied that he did, although he did do much reading on the subject.[22]

The Asian novels

On his return to France, Malraux published The Temptation of the West (1926). The work was in the form of an exchange of letters between a Westerner and an Asian, comparing aspects of the two cultures. This was followed by his first novel The Conquerors (1928), and then by The Royal Way (1930) which reflected some of his Cambodian experiences.[23] The American literary critic Dennis Roak described Les Conquérants as influenced by The Seven Pillars of Wisdom as it was narrated in the present tense "...with its staccato snatches of dialogue and the images of sound and sight, light and darkness, which create a compellingly haunting atmosphere."[14] Les Conquérants was set in the summer of 1925 against the backdrop of the general strike called by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Kuomintang in Hong Kong and Canton, the novel concerns political intrigue amongst the "anti-imperialist" camp.[24] The novel is narrated by an unnamed Frenchman who travels from Saigon to Hong Kong to Canton to meet an old friend named Garine who is a professional revolutionary working with Mikhail Borodin, who in real life was the Comintern's principal agent in China.[24] The Kuomintang are depicted rather unflatteringly as conservative Chinese nationalists uninterested in social reform, another faction is led by Hong, a Chinese assassin committed to revolutionary violence for the sake of violence, and only the Communists are portrayed relatively favorably.[25] Much of the dramatic tension between the novel concerns a three-way struggle between the hero, Garine and Borodin who is only interested in using the revolution in China to achieve Soviet foreign policy goals.[25] The fact that the European characters are considerably better drawn than the Asian characters reflected Malraux's understanding of China at the time as more of an exotic place where Europeans played out their own dramas rather than a place to be understood in its own right. Initially, Malraux's writings on Asia reflected the influence of "Orientalism" presenting the Far East as strange, exotic, decadent, mysterious, sensuous and violent, but Malraux's picture of China grew somewhat more humanized and understanding as Malraux disregarded his Orientalist and Eurocentric viewpoint in favor of one that presented the Chinese as fellow human beings.[26]

The second of Malraux's Asian novels was the semi-autobiographical La Voie Royale which relates the adventures of a Frenchman Claude Vannec who together with his Danish friend Perken head down the royal road of the title into the jungle of Cambodia with the intention of stealing bas-relief sculptures from the ruins of Hindu temples.[27] After many perilous adventures, Vannec and Perken are captured by hostile tribesmen and find an old friend of Perken's, Grabot, who had already been captured for some time.[28] Grabot, a deserter from the French Foreign Legion had been reduced to nothing as his captors blinded him and left him tied to a stake starving, a stark picture of human degradation.[28] The three Europeans escape, but Perken is wounded and dies of an infection.[28] Through ostensibly an adventure novel, La Voie Royale is in fact a philosophical novel concerned with existential questions about the meaning of life.[28] The book was a failure at the time as the publishers marketed it as a stirring adventure story set in far-off, exotic, Cambodia which confused many readers who, instead, found a novel pondering deep philosophical questions.[29]

In his Asian novels Malraux used Asia as a stick to beat Europe with as he argued that after World War I the ideal of progress of a Europe getting better and better for the general advancement of humanity was dead.[30] As such, Malraux now argued that European civilization was faced with a Nietzschean void, a twilight world, without God or progress, in which the old values had proven worthless and a sense of spirituality that had once existed was gone.[30] An agnostic, but an intensely spiritual man, Malraux maintained that what was needed was an "aesthetic spirituality" in which love of 'Art' and 'Civilization' would allow one to appreciate le sacré in life, a sensibility that was both tragic and awe-inspiring as one surveyed all of the cultural treasures of the world, a mystical sense of humanity's place in a universe that was as astonishingly beautiful as it was mysterious.[30] Malraux argued that as death is inevitable and in a world devoid of meaning, which thus was "absurd", only art could offer meaning in an "absurd" world.[31] Malraux argued that art transcended time as art allowed one to connect with the past, and the very act of appreciating art was itself an act of art as the love of art was part of a continuation of endless artistic metamorphosis that constantly created something new.[31] Malraux argued that as different types of art went in and out of style, the revival of a style was a metamorphosis as art could never be appreciated in exactly the same way as it was in the past.[31] As art was timeless, it conquered time and death as artworks lived on after the death of the artist.[31] The American literary critic Jean-Pierre Hérubel wrote that Malraux never entirely worked out a coherent philosophy as his mystical Weltanschauung (world view) was based more upon emotion than logic.[30] In Malraux's viewpoint, of all the professions, the artist was the most important as artists were the explorers and voyagers of the human spirit, as artistic creation was the highest form of human achievement for only art could illustrate humanity's relationship with the universe. As Malraux wrote, "there is something far greater than history and it is the persistence of genius".[30] Hérubel argued that it is fruitless to attempt to criticize Malraux for his lack of methodological consistency as Malraux cultivated a poetical sensibility, a certain lyrical style, that appealed more to the heart than to the brain.[32] Malraux was a proud Frenchman, but he also saw himself as a citizen of the world, a man who loved the cultural achievements of all of the civilizations across the globe.[32] At the same time, Malraux criticized those intellectuals who wanted to retreat into the ivory tower, instead arguing that it was the duty of intellectuals to participate and fight (both metaphorically and literally) in the great political causes of the day, that the only truly great causes were the ones that one was willing to die for.[15]

In 1933 Malraux published Man's Fate (La Condition Humaine), a novel about the 1927 failed Communist rebellion in Shanghai. Despite Malraux's attempts to present his Chinese characters as more three dimensional and developed than he did in Les Conquérants, his biographer Oliver Todd wrote he could not "quite break clear of a conventional idea of China with coolies, bamboo shoots, opium smokers, destitutes, and prostitutes", which were the standard French stereotypes of China at the time.[33] The work was awarded the 1933 Prix Goncourt.[34] After the breakdown of his marriage with Clara, Malraux lived with journalist and novelist Josette Clotis, starting in 1933. Malraux and Josette had two sons: Pierre-Gauthier (1940–1961) and Vincent (1943–1961). During 1944, while Malraux was fighting in Alsace, Josette died, aged 34, when she slipped while boarding a train. His two sons died together in 1961 in an automobile accident.

Searching for lost cities

On 22 February 1934, Malraux together with Édouard Corniglion-Molinier embarked on a much publicized expedition to find the lost capital of the Queen of Sheba mentioned in the Old Testament.[35] Saudi Arabia and Yemen were both remote, dangerous places that few Westerners visited at the time, and what made the expedition especially dangerous was while Malraux was searching for the lost cities of Sheba, King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia invaded Yemen, and the ensuing Saudi–Yemeni war greatly complicated Malraux's search.[36] After several weeks of flying over the deserts in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, Malraux returned to France to announce that the ruins he found up in the mountains of Yemen were the capital of the Queen of Sheba.[35] Though Malraux's claim is not generally accepted by archeologists, the expedition bolstered Malraux's fame and provided the material for several of his later essays.[35]

Spanish Civil War

During the 1930s, Malraux was active in the anti-fascist Popular Front in France. At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War he joined the Republican forces in Spain, serving in and helping to organize the small Spanish Republican Air Force.[37] Curtis Cate, one of his biographers, writes that Malraux was slightly wounded twice during efforts to stop the Battle of Madrid in 1936 as the Spanish Nationalists attempted to take Madrid, but the historian Hugh Thomas argues otherwise.

The French government sent aircraft to Republican forces in Spain, but they were obsolete by the standards of 1936. They were mainly Potez 540 bombers and Dewoitine D.372 fighters. The slow Potez 540 rarely survived three months of air missions, flying at 160 knots against enemy fighters flying at more than 250 knots. Few of the fighters proved to be airworthy, and they were delivered intentionally without guns or gunsights. The Ministry of Defense of France had feared that modern types of planes would easily be captured by the German Condor Legion fighting with General Francisco Franco, and the lesser models were a way of maintaining official "neutrality".[38] The planes were surpassed by more modern types introduced by the end of 1936 on both sides.

The Republic circulated photos of Malraux standing next to some Potez 540 bombers suggesting that France was on their side, at a time when France and the United Kingdom had declared official neutrality. But Malraux's commitment to the Republicans was personal, like that of many other foreign volunteers, and there was never any suggestion that he was there at the behest of the French Government. Malraux himself was not a pilot, and never claimed to be one, but his leadership qualities seem to have been recognized because he was made Squadron Leader of the 'España' squadron. Acutely aware of the Republicans' inferior armaments, of which outdated aircraft were just one example, he toured the United States to raise funds for the cause. In 1938 he published L'Espoir (Man's Hope), a novel influenced by his Spanish war experiences.[39]

Malraux's participation in major historical events such as the Spanish Civil War inevitably brought him determined adversaries as well as strong supporters, and the resulting polarization of opinion has colored, and rendered questionable, much that has been written about his life. Fellow combatants praised Malraux's leadership and sense of camaraderie[40] While André Marty of the Comintern called him as an "adventurer" for his high profile and demands on the Spanish Republican government.[41] The British historian Antony Beevor also claims that "Malraux stands out, not just because he was a mythomaniac in his claims of martial heroism – in Spain and later in the French Resistance – but because he cynically exploited the opportunity for intellectual heroism in the legend of the Spanish Republic."[41]

In any case, Malraux's participation in events such as the Spanish Civil War has tended to distract attention from his important literary achievement. Malraux saw himself first and foremost as a writer and thinker (and not a "man of action" as biographers so often portray him) but his extremely eventful life – a far cry from the stereotype of the French intellectual confined to his study or a Left Bank café – has tended to obscure this fact. As a result, his literary works, including his important works on the theory of art, have received less attention than one might expect, especially in Anglophone countries.[42]

World War II

At the beginning of the Second World War, Malraux joined the French Army. He was captured in 1940 during the Battle of France but escaped and later joined the French Resistance.[43] In 1944, he was captured by the Gestapo.[44] He later commanded the Brigade Alsace-Lorraine in defence of Strasbourg and in the attack on Stuttgart.[45]

André's half-brother, Claude, a Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, was also captured by the Germans, and executed at Gross-Rosen concentration camp in 1944.[46]

Otto Abetz was the German Ambassador, and produced a series of "black lists" of authors forbidden to be read, circulated or sold in Nazi occupied France. These included anything written by a Jew, a communist, an Anglo-Saxon or anyone else who was anti-Germanic or anti-fascist. Louis Aragon and André Malraux were both on these "Otto Lists" of forbidden authors.[47]

After the war, Malraux was awarded the Médaille de la Résistance and the Croix de guerre. The British awarded him the Distinguished Service Order, for his work with British liaison officers in Corrèze, Dordogne and Lot. After Dordogne was liberated, Malraux led a battalion of former resistance fighters to Alsace-Lorraine, where they fought alongside the First Army.[48]

During the war, he worked on his last novel, The Struggle with the Angel, the title drawn from the story of the Biblical Jacob. The manuscript was destroyed by the Gestapo after his capture in 1944. A surviving first section, titled The Walnut Trees of Altenburg, was published after the war.

After the war

Shortly after the war, General Charles de Gaulle appointed Malraux as his Minister for Information (1945–1946). Soon after, he completed his first book on art, The Psychology of Art, published in three volumes (1947–1949). The work was subsequently revised and republished in one volume as The Voices of Silence (Les Voix du Silence), the first part of which has been published separately as The Museum without Walls. Other important works on the theory of art were to follow. These included the three-volume Metamorphosis of the Gods and Precarious Man and Literature, the latter published posthumously in 1977. In 1948, Malraux married a second time, to Marie-Madeleine Lioux, a concert pianist and the widow of his half-brother, Roland Malraux. They separated in 1966. Subsequently, Malraux lived with Louise de Vilmorin in the Vilmorin family château at Verrières-le-Buisson, Essonne, a suburb southwest of Paris. Vilmorin was best known as a writer of delicate but mordant tales, often set in aristocratic or artistic milieu. Her most famous novel was Madame de..., published in 1951, which was adapted into the celebrated film The Earrings of Madame de… (1953), directed by Max Ophüls and starring Charles Boyer, Danielle Darrieux and Vittorio de Sica. Vilmorin's other works included Juliette, La lettre dans un taxi, Les belles amours, Saintes-Unefois, and Intimités. Her letters to Jean Cocteau were published after the death of both correspondents. After Louise's death, Malraux spent his final years with her relative, Sophie de Vilmorin.

In 1957, Malraux published the first volume of his trilogy on art entitled The Metamorphosis of the Gods. The second two volumes (not yet translated into English) were published shortly before he died in 1976. They are entitled L'Irréel and L'Intemporel and discuss artistic developments from the Renaissance to modern times. Malraux also initiated the series Arts of Mankind, an ambitious survey of world art that generated more than thirty large, illustrated volumes.

When de Gaulle returned to the French presidency in 1958, Malraux became France's first Minister of Cultural Affairs, a post he held from 1958 to 1969. On 7 February 1962, Malraux was the target of an assassination attempt by the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), which set off a bomb to his apartment building that failed to kill its intended target, but did leave a four-year-old girl who was living in the adjoining apartment blinded by the shrapnel.[50] Ironically, Malraux was a lukewarm supporter of de Gaulle's decision to grant independence to Algeria, but the OAS was not aware of this, and had decided to assassinate Malraux as a high-profile minister.

Among many initiatives, Malraux launched an innovative (and subsequently widely imitated) program to clean the blackened façades of notable French buildings, revealing the natural stone underneath.[51] He also created a number of maisons de la culture in provincial cities and worked to preserve France's national heritage by promoting industrial archaeology.[52] An intellectual who took the arts very seriously, Malraux saw his mission as Culture Minister to preserve France's heritage and to improve the cultural levels of the masses.[53] Malraux's efforts to promote French culture mostly concerned renewing old or building new libraries, art galleries, museums, theatres, opera houses, and maisons de la culture (centres built in provincial cities that were a mixture of a library, art gallery and theatre).[52] Film, television and music took less of Malraux's time, and the changing demographics caused by immigration from the Third World stymied his efforts to promote French high culture, as many immigrants from Muslim and African nations did not find French high culture that compelling.[52] A passionate bibliophile, Malraux built up a huge collections of books both as a cultural minister for the nation and as a man for himself.[54]

Malraux was an outspoken supporter of the Bangladesh liberation movement during the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh and despite his age seriously considered joining the struggle. When Indira Gandhi came to Paris in November 1971, there was extensive discussion between them about the situation in Bangladesh.

During this post-war period, Malraux published a series of semi-autobiographical works, the first entitled Antimémoires (1967). A later volume in the series, Lazarus, is a reflection on death occasioned by his experiences during a serious illness. La Tête d'obsidienne (1974) (translated as Picasso's Mask) concerns Picasso, and visual art more generally. In his last book, published posthumously in 1977, L'Homme précaire et la littérature, Malraux propounded the theory that there was a bibliothèque imaginaire where writers created works that influenced subsequent writers much as painters learned their craft by studying the old masters; once they have understood the work of the old masters, writers would sally forth with the knowledge gained to create new works that added to the growing and never-ending bibliothèque imaginaire.[52] An elitist who appreciated what he saw as the high culture of all the nations of the world, Malraux was especially interested in art history and archaeology, and saw his duty as a writer to share what he knew with ordinary people.[52] An aesthete, Malraux believed that art was spiritually enriching and necessary for humanity.[55]

Death

Malraux died in Créteil, near Paris, on 23 November 1976 from a lung embolism. He was a heavy smoker and had cancer [1]. He was buried in the Verrières-le-Buisson (Essonne) cemetery. In recognition of his contributions to French culture, his ashes were moved to the Panthéon in Paris during 1996, on the twentieth anniversary of his death.

Legacy and honours

- 1933, Prix Goncourt

- Médaille de la Résistance

- Croix de guerre

- Distinguished Service Order (United Kingdom)

- 1959, honorary degree, University of São Paulo[56]

- Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding, 1974 (India)

There is now a large and steadily growing body of critical commentary on Malraux's literary œuvre, including his very extensive writings on art. Unfortunately, some of his works, including the last two volumes of The Metamorphosis of the Gods (L'Irréel and L'Intemporel) are not yet available in English translation. Malraux's works on the theory of art contain a revolutionary approach to art that challenges the Enlightenment tradition that treats art simply as a source of "aesthetic pleasure". However, as French writer André Brincourt has commented, Malraux's books on art have been "skimmed a lot but very little read"[57] (this is especially true in Anglophone countries) and the radical implications of his thinking are often missed. A particularly important aspect of Malraux's thinking about art is his explanation of the capacity of art to transcend time. In contrast to the traditional notion that art endures because it is timeless ("eternal"), Malraux argues that art lives on through metamorphosis – a process of resuscitation (where the work had fallen into obscurity) and transformation in meaning.[58]

- 1968, an international Malraux Society was founded in the United States. It produces the journal Revue André Malraux Review, Michel Lantelme, editor, at University of Oklahoma.[59]

- Another international Malraux association, the Amitiés internationales André Malraux, is based in Paris.

- A French-language website, Site littéraire André Malraux, offers research, information, and critical commentary about Malraux's works.[60]

- A quote from Malraux's Antimémoires was included in the original 1997 English translation of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. The quote, "What is a man? A miserable little pile of secrets" was part of a surprisingly famous and popular monologue early in the game.[61][62]

- One of the primary "feeder" schools of the Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle in London is named in honour of André Malraux.

Bibliography

- Lunes en Papier, 1923 (Paper Moons, 2005)

- La Tentation de l'Occident, 1926 (The Temptation of the West, 1926)

- Royaume-Farfelu, 1928 (The Kingdom of Farfelu, 2005)

- Malraux, André (1928). Les Conquérants (The Conquerors). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50290-8. (reprint University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-226-50290-8)

- La Voie royale, 1930 (The Royal Way or The Way of the Kings, 1930)

- La Condition humaine, 1933 (Man's Fate, 1934)

- Le Temps du mépris, 1935 (Days of Wrath, 1935)

- L'Espoir, 1937 (Man's Hope, 1938)

- Malraux, André (1948). Les Noyers de l'Altenburg (The Walnut Trees of Altenburg). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50289-2. (reprint University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-226-50289-2)

- La Psychologie de l'Art, 1947–1949 (The Psychology of Art)

- Le Musée imaginaire de la sculpture mondiale (1952–54) (The Imaginary Museum of World Sculpture (in three volumes))

- Les Voix du silence, 1951 (The Voices of Silence, 1953)

- La Métamorphose des dieux (English translation: The Metamorphosis of the Gods, by Stuart Gilbert):

- Vol 1. Le Surnaturel, 1957

- Vol 2. L'Irréel, 1974

- Vol 3. L'Intemporel, 1976

- Antimémoires, 1967 (Anti-Memoirs, 1968 – autobiography)

- Les Chênes qu'on abat, 1971 (Felled Oaks or The Fallen Oaks)

- Lazare, 1974 (Lazarus, 1977)

- L'Homme précaire et la littérature, 1977

- Saturne: Le destin, l'art et Goya, (Paris: Gallimard, 1978) (Translation of an earlier edition published in 1957: Malraux, André. * Saturn: An Essay on Goya. Translated by C.W. Chilton. London: Phaidon Press, 1957.)

- Lettres choisies, 1920–1976. Paris, Gallimard, 2012.

For a more complete bibliography, see site littéraire André Malraux.[63]

Exhibitions

- André Malraux, Fondation Maeght, Vence, 1973

- André Malraux et la modernité - le dernier des romantiques, Centennial Exhibition of his Birth, Musée de la Vie romantique, Paris, 2001, by Solange Thierry, with contributions by Marc Lambron, Solange Thierry, Daniel Marchesseau, Pierre Cabanne, Antoine Terrasse, Christiane Moatti, Gilles Béguin and Germain Viatte (ISBN 978-2-87900-558-4)

References

- ^ a b "Biographie détaillée" Archived 5 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, André Malraux Website, accessed 3 Sep 2010

- ^ Cate, p. 4

- ^ Cate, p. 153

- ^ Katherine Knorr (31 May 2001). "Andre Malraux, the Great Pretender". The New York Times.

- ^ Biographie détaillée Archived 5 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Malraux.org. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- ^ Cate, pp. 388–389

- ^ a b Batchelor, R "The Presence of Nietzsche in André Malraux" pages 218-229 from Journal of European Studies, Issue 3, 1973 page 218.

- ^ Batchelor, R "The Presence of Nietzsche in André Malraux" pages 218-229 from Journal of European Studies, Issue 3, 1973 page 219.

- ^ Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from page 218.

- ^ Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from pages 218-219.

- ^ Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from page 219.

- ^ Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from pages 219-220.

- ^ Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from pages 222-223.

- ^ a b Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from page 223.

- ^ a b c Langlois, Walter "André Malraux (1901-1976)" pages 683-687 from The French Review, Vol. 50, No. 5, April 1977 page 685.

- ^ Cate, pp. 53–58

- ^ "Buried Treasure". The Economist. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Hierarchies of value at Angkor Wat | Lindsay French. Academia.edu. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- ^ Yves Le Jariel, L'ami oublié de Malraux en Indochine, Paul Monin (1890-1929)

- ^ Cate, pp. 86–96

- ^ Roak, Denis "Malraux and T. E. Lawrence" pages 218-224 from The Modern Language Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 1966 from page 220.

- ^ Xu, Anne Lijing The Sublime Writer and the Lure of Action: Malraux, Brecht, and Lu Xun on China and Beyond, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007 page 12.

- ^ Cate, p. 159

- ^ a b Harris, Geoffrey André Malraux: A Reassessment, London: Macmillan 1995 page 45.

- ^ a b Harris, Geoffrey André Malraux: A Reassessment, London: Macmillan 1995 page 46.

- ^ Xu, Anne Lijing The Sublime Writer and the Lure of Action: Malraux, Brecht, and Lu Xun on China and Beyond, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007 pages 11 & 13.

- ^ Harris, Geoffrey André Malraux: A Reassessment, London: Macmillan 1995 page 69.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Geoffrey André Malraux: A Reassessment, London: Macmillan 1995 page 70.

- ^ Harris, Geoffrey André Malraux: A Reassessment, London: Macmillan 1995 page 71.

- ^ a b c d e Hérubel, Jean-Pierre "André Malraux and the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs: A Bibliographic Essay" pages 556-575 from Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 4 Fall 2000 page 561

- ^ a b c d Sypher, Wylie "Aesthetic of Doom: Malraux" pages 146-165 from Salmagundi, No. 68/69, Fall 1985-Winter 1986 page 148.

- ^ a b Hérubel, Jean-Pierre "André Malraux and the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs: A Bibliographic Essay" pages 556-575 from Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 4 Fall 2000 page 562

- ^ Todd, Oliver Malraux: A Life, New York: Alfred Knopf, 2005 page 110.

- ^ Cate, pp. 170–181

- ^ a b c Harris, Geoffrey André Malraux: A Reassessment, London: Macmillan 1995 page 118.

- ^ Langlois, Walter In search of Sheba: an Arabian adventure : André Malraux and Edouard Corniglon-Molinier, Yemen, 1934 Knoxville: Malraux Society, 2006 pages 267-269

- ^ Cate, pp. 228–242

- ^ Cate, p. 235

- ^ John Sturrock (9 August 2001). "The Man from Nowhere". The London Review of Books. Vol. 23, no. 15.

- ^ Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009). pp. 25–27.

- ^ a b Beevor, p. 140

- ^ Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure, André Malraux's Theory of Art (Rodopi, 2009)

- ^ Cate, pp. 278–287

- ^ Cate, pp. 328–332

- ^ Cate, pp. 340–349

- ^ see French version of Wikipedia entry: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Malraux

- ^ Moorehead, Caroline. 2011. A Train in Winter. Pages 21-22.

- ^ "Recommendations for Honours and Awards (Army)—Malraux, Andre" (fee usually required to view full pdf of original recommendation). DocumentsOnline. The National Archives. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ Scott, Janny (11 September 2011). "In Oral History, Jacqueline Kennedy Speaks Candidly After the Assassination". The New York Times.

- ^ Shepard, Todd The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008 page 183.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian. Entry for AM in The Oxford Dictionary of Art (Oxford, 2004). Accessed on 6/28/11 at: http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Andre_Malraux.aspx#4

- ^ a b c d e Hérubel, Jean-Pierre "André Malraux and the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs: A Bibliographic Essay" pages 556-575 from Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 4 Fall 2000 page 557

- ^ Hérubel, Jean-Pierre "André Malraux and the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs: A Bibliographic Essay" pages 556-575 from Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 4 Fall 2000 pages 556-557

- ^ Hérubel, Jean-Pierre "André Malraux and the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs: A Bibliographic Essay" pages 556-575 from Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 4 Fall 2000 page 558

- ^ Hérubel, Jean-Pierre "André Malraux and the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs: A Bibliographic Essay" pages 556-575 from Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 4 Fall 2000 pages 557-558

- ^ Honorary Doctorates between the decades of 1950s and 1960s from the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

- ^ Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009, p. 21

- ^ Derek Allan. Art and Time Archived 18 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge Scholars: 2013

- ^ ''Revue André Malraux Review''. Revueandremalraux.com. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- ^ Site littéraire André Malraux. Malraux.org. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- ^ Mandelin, Clyde (8 June 2013). "How Symphony of the Night's "Miserable Pile of Secrets" Scene Works in Japanese". Legends of Localization. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Blaustein, Jeremy (18 July 2019). "The bizarre, true story of Metal Gear Solid's English translation". Polygon. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "Bibliographie d'AM". malraux.org.

Further reading

- Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art (Amsterdam, Rodopi: 2009) Derek Allan

- André Malraux (1960) by Geoffrey H. Hartman

- André Malraux: The Indochina adventure (1960) by Walter Langlois (New York Praeger).

- Malraux, André (1976). Le Miroir des Limbes. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-010864-3.

- Malraux (1971) by Pierre Galante ()

- André Malraux: A Biography (1997) by Curtis Cate Fromm Publishing (ISBN 2-08-066795-5)

- Malraux ou la Lutte avec l'ange. Art, histoire et religion (2001) by Raphaël Aubert (ISBN 2-8309-1026-5)

- Malraux : A Life (2005) by Olivier Todd (ISBN 0-375-40702-2) Review by Christopher Hitchens

- Dits et écrits d'André Malraux : Bibliographie commentée (2003) by Jacques Chanussot and Claude Travi (ISBN 2-905965-88-6)

- André Malraux (2003) by Roberta Newnham (ISBN 978-1-84150-854-2)

- David Bevan (1986). André Malraux: towards the expression of transcendence. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-0552-0.

- Jean François Lyotard (1999). Signed, Malraux. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3106-3.

- Geoffrey T. Harris (1996). André Malraux: a reassessment. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-12925-5.

- Antony Beevor (2006). The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303765-1.

- Andre Malraux: Tragic Humanist (1963) by Charles D. Blend, Ohio State University Press (LCCN 62-19865)

- Mona Lisa's Escort: André Malraux and the Reinvention of French Culture (1999) by Herman Lebovics, Cornell University Press.

- Derek Allan, Art and Time, Cambridge Scholars, 2013.

- Leys, Simon (Pierre Ryckmans), 'Malraux', in The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays (Melbourne: Black Inc, 2011), pp. 144–152. ISBN 978-1-8639-5532-4

External links

- Amitiés Internationales André Malraux The official site of the French André Malraux Society: Malraux and culture. (in French)

- André Malraux The site of research and information dedicated to André Malraux: literature, art, religion, history and culture. (in French)

- Petri Liukkonen. "André Malraux". Books and Writers.

- Université McGill: le roman selon les romanciers (French) Inventory and analysis of André Malraux non-novelistic writings (in French)

- Malraux's early, surrealist writings (in English)

- 'Malraux, Literature and Art' – Essays by Derek Allan (in English)

- A multimedia adaptation of Voices of silence (in French)

- "Andre Malraux and the Arts" – Henri Peyre, The Baltimore Museum of Art: Baltimore, Maryland, 1964 – Accessed 26 June 2012 (in English)

- Fondation André Malraux (in French)

- Foundation André Malraux (in English)

- Villa André Malraux

- Literature by and about André Malraux [2]

- 1901 births

- 1976 deaths

- Writers from Paris

- French travel writers

- French Resistance members

- Philosophers of art

- French art historians

- French military personnel of World War II

- French people of the Spanish Civil War

- French Ministers of Culture

- Ministers of Information of France

- People with Tourette syndrome

- Prix Goncourt winners

- Prix Interallié winners

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France)

- Recipients of the Resistance Medal

- Companions of the Liberation

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Burials at the Panthéon, Paris

- 20th-century French novelists

- 20th-century French historians

- French male novelists