Nauru Regional Processing Centre

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Cohesion, structure. (June 2020) |

Tents and cots from the Nauru offshore processing facility in September 2012 | |

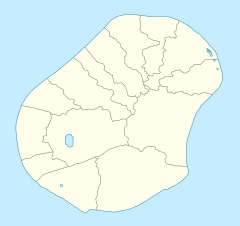

| Location | Meneng District, Nauru |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 0°32′28″S 166°55′48″E / 0.541°S 166.930°E |

| Status | Operational |

| Opened | 2001 |

| Closed | 2018? |

| Country | Nauru |

The Nauru Regional Processing Centre was an offshore Australian immigration detention facility, located on the South Pacific island nation of Nauru. The use of immigration detention facilities is part of a policy of mandatory detention in Australia.

The Nauru facility was opened in 2001 as part of the Howard Government's Pacific Solution. The centre was suspended in 2008 to fulfil an election promise by the Rudd Government, but was reopened in August 2012 by the Gillard government after a large increase in the number of maritime arrivals by asylum seekers[1]and pressure from the Abbott opposition.[2] Current Coalition and Labor Party policy states that because all detainees attempted to reach Australia by boat, they will never be settled in Australia,[3] even though many of the asylum seekers detained on the island have been assessed as genuine refugees.[4]

The highest population at the centre was 1,233 detainees in August 2014. A number of detainees have since been returned to their countries of origin, including Iraq and Iran.[4]

By November 2018, some refugees from Nauru (430 in total from both offshore facilities) had been resettled in the United States, but hopes of the US taking more had faded. Although New Zealand has repeatedly offered to take 150 per year, the Australian Government would not agree to this. There were still 23 children on the island, although the government had bowed to public pressure and started removing families with children, after reports of suicidal behaviour and resignation syndrome had emerged.[5]

In February 2019, the last four children on the island (of an original 200 in detention on Nauru in 2013) were resettled in United States with their families.[6] By 31 March 2019, there were no people held in the detention centre, which had been closed;[7] however as of March 2020, there were 211 refugees and asylum seekers remaining on the island.[8]

History

2001: establishment

The establishment of an offshore processing centre on Nauru was based on a Statement of Principles, signed on 10 September 2001 by the President of Nauru, René Harris, and Australia's then-Minister for Defence, Peter Reith. The statement opened the way to establish a detention centre for up to 800 people and was accompanied by a pledge of A$20 million for development activities. The initial detainees were to be people rescued by the MV Tampa (Tampa affair), with the understanding that they would leave Nauru by May 2002. Subsequently, a memorandum of understanding was signed on 11 December, boosting accommodation to 1,200 and the promised development activity by an additional $10 million.[9]

Initial plans were for asylum seekers to be housed in modern, air-conditioned housing which had been built for the games of the International Weightlifting Federation. This plan was changed after landowners' requests for extra compensation were rejected.[9] Two camps were built.[10] The first camp, called "Topside", was at an old sports ground and oval in the Meneng District (0°32′26″S 166°55′47″E / 0.540564°S 166.929703°E). The second camp, called "State House", was on the site of the old Presidential quarters also in the Meneng District (0°32′51″S 166°56′23″E / 0.547597°S 166.939697°E).[9][11][12][13] A month-long hunger strike began on 10 December 2003.[14] It included mostly Hazara from Afghanistan rescued during the Tampa affair, who were protesting for the review of their cases.

By July 2005, 32 people were detained in Nauru as asylum seekers: 16 Iraqis, 11 Afghans, 2 Iranians, 2 Bangladeshis, and 1 Pakistani.[15] All but two Iraqis were released to Australia, the last group of 25 leaving on 1 November 2005. The remaining two Iraqis stayed in custody for over a year. The last one was finally accepted by an undisclosed Scandinavian country after five years in detention, in January 2007. The other was in an Australian hospital at the time, and was later given permission to remain in Australia while his asylum case was being decided. In September 2006, a group of eight Burmese Rohingya men were transferred there from Christmas Island.[16] On 15 March 2007 the Australian Government announced that 83 Tamils from Sri Lanka would be transferred from Christmas Island to the Nauru detention centre.[17] They arrived in Nauru by the end of the month.

2007: closing

In December 2007, newly elected Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced that his country would no longer make use of the Nauru detention centre, and would put an immediate end to the "Pacific Solution". The last remaining Burmese and Sri Lankan detainees were granted residency rights in Australia.[18][19] Nauru reacted with concern at the prospect of potentially losing much-needed aid from Australia.[20]

2012: re-opening

In August 2012, the Labor Government led by Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced the resumption of the transfer of asylum seekers arriving by boat in Australia to Nauru (and Manus Island, PNG). Australia signed an initial Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Nauru on 29 August 2012.[21] The first group arrived the following month.[22][23] The re-opening of the centres sparked criticism of Australia's Labor Government after the United Nations refused to assist the government on the mandatory measures.[23][24] In November 2012, an Amnesty International team visited the camp and described it as "a human rights catastrophe [...] a toxic mix of uncertainty, unlawful detention and inhumane conditions".[25][26]

The MOU between Nauru and Australia was renegotiated on 3 August 2013. Clause 12 of the 2013 MOU allows for resettlement of refugees in Nauru: "The Republic of Nauru undertakes to enable Transferees who it determines are in need of international protection to settle in Nauru, subject to agreement between Participants on arrangements and numbers".[27]

July 2013: riot

On 19 July 2013 a riot occurred at the detention centre and caused $60 million damage. Police and guards had rocks and sticks thrown at them. Four people were hospitalised with minor injuries.[28] Other people were treated for bruising and cuts.[29] The riot began at 3 p.m. when the detainees staged a protest.[30] Up to 200 detainees escaped and about 60[31] were held overnight at the island's police station.[32] Several vehicles[33] and buildings including accommodation blocks for up to 600 people, offices, dining room, and the health centre were destroyed by fire. This is about 80 percent of the centre's buildings.[28][31] 129 of 545 male detainees were identified as being involved in the rioting and were detained in the police watch house.[28]

In October 2015 Nauru declared that the asylum seekers housed in the detention centre now had freedom of movement around the island. Given reports that three women had been raped and numerous other assaults have taken place against asylum seekers it was reported that this may actually increase the amount of danger to them.[34]

Nov 2016: United States resettlement deal

In November 2016 it was announced that a deal had been made with the United States to resettle people in detention on Nauru and Manus Islands.[35] There is very little public information available about how many of these refugees will be resettled by the United States; initial reports however estimated up to 1,250 refugees would be resettled from Nauru and Manus Island.[36] Then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull indicated that the priority is "very much on the most vulnerable",[37] particularly families on Nauru. On 27 February 2017, the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection told a Senate Estimates Committee that preliminary screening had started as part of the resettlement deal, but officials from the United States Department of Homeland Security had not yet been authorised to start formally vetting applicants.[36]

Feb 2019: last children off Nauru; "Medevac" bill passed

On 3 February 2019, prime minister Scott Morrison announced that the last four families with children left on Nauru were about to leave for the US. They would be the last of the more than 200 children who had been held on the island when the Coalition won government in 2013.[6]

On 13 February 2019, a bill which became known as the "Medevac bill" was narrowly passed by the Australian parliament allowing doctors to have more say in the process by which asylum seekers on Manus and Nauru may be medically evacuated and brought to the mainland for treatment. The approval of two doctors is required, but approval may still be overridden by the home affairs minister in one of three areas. Human rights advocates hailed the decision, with one calling it a “tipping point as a country”, with the weight of public opinion believing that sick people need treatment.[38][39][40]

Aug-Sept 2019 update on numbers

The Australian government reported that as of 28 August 2019 there were 288 people left on Nauru; 330 had been resettled in the US; and another 85 people had been approved for resettlement in the US, but had not yet left.[41]

It was reported that as of 30 September, total numbers of asylum seekers left in PNG and Nauru was 562 (23 percent of the peak, in June 2014), and another 1,117 people had been "temporarily transferred to Australia for medical treatment or as accompanying family members". Numbers for each facility were not given separately.[42]

March-May 2020

In March 2020, Home Affairs told the Senate estimates committee that "211 refugees and asylum seekers remained on Nauru, 228 in Papua New Guinea, and about 1,220, including their dependents, were in Australia to receive medical treatment". Transfer and resettlement of approved refugees in the US was proceeding during the COVID-19 pandemic.[8]

Operators

- 2012 - October 2017: Broadspectrum (formerly known as Transfield Services).

- Later, security was subcontracted to Wilson Security

- October 2017 - November 2018: Canstruct International contract worth $591 million[43]

- November 2018 onwards: A Nauruan Government commercial entity[43]

Conditions and human rights issues

The conditions at the Nauru detention centre were initially described as harsh with only basic health facilities.[44] In 2002, detainees deplored the water shortages and overcrowded conditions.[44] There were only very limited education services for children.[44] On 19 July 2013 there was a major riot in the detention centre. Several buildings were destroyed by fire, and damage was estimated at $60 million. Hunger strikes and self-harm, including detainees sewing their lips together,[45] have been reported at the facility, as well as at least two people setting themselves on fire.[46] Attempted suicides were also reported.[47] Medical staff have been provided by International Organization for Migration.

An overwhelming sense of despair has been repeatedly expressed by detainees because of the uncertainty of their situation and their remoteness from loved ones.[48] In 2013, a veteran nurse described the detention centre as "like a concentration camp".[47]

In 2015, several staff members from the detention centre wrote an open letter claiming that multiple instances of sexual abuse against women and children had occurred.[49] The letter claimed that the Australian government had been aware of these abuses for over 18 months.[50] This letter added weight to the Moss review which found it possible that "guards had traded marijuana for sexual favours with asylum seeker children".[51][52][53]

In 2018, reports of children engaging in self-harm and attempting suicide drew attention back to the conditions at the centre. Children as young as eight were documented as exhibiting suicidal behaviours, and an estimated 30 children were described as suffering from resignation syndrome, a progressive, deteriorating psychiatric condition that can be fatal. Extreme trauma experienced both in their country of origin and in their daily lives at the camp, coupled with a sense of hopelessness and abandonment, are thought to have contributed to the onset of this condition.[54]

Media access

Media access to the island of Nauru, and the Regional Processing Centre in particular, is tightly controlled by the Nauruan government. In January 2014, the Nauru government announced it was raising the cost of a media visa to the island from AUD$200 to $8,000, non-refundable if the visa was not granted.[55] Since then journalists from Al Jazeera, the ABC, SBS and The Guardian have stated that they have applied for media visas with no success. The last journalist to visit the island before the commencement of Operation Sovereign Borders was Nick Bryant of the BBC.[56]

In 2014 the National Security Legislation Amendment Act (No. 1) made it a crime, punishable with up to a 10-year prison sentence, to disclose any special intelligence operation, including relating to asylum seekers. This provided little protection to journalists seeking to report on information from whistle-blowers.[57] It caused professional journalists as well as teachers and health professionals employed in these detention centres, to be silenced.[58] Journalists were prevented from entering or reporting and staff members were gagged under draconian employment contracts that prevented them from speaking about anything happening in Australia’s offshore detention centre, under threat of a prison sentence.[59] The Secrecy and Disclosure Provisions of the 1 July 2015 Australian Border Force Act ruled that workers who spoke of any incidents from within one of the centres would receive a 2-year prison sentence. This was later watered down in amendments put forward by Peter Dutton in August 2017, after doctors and other health professionals had mounted a high court challenge.[60] The amendments would apply retrospectively and stipulated that the secrecy provision would only apply to information that could compromise Australia’s security, defence or international relations, interfere with criminal investigations offences, or affect sensitive personal or commercial matters.[61]

In October 2015, Chris Kenny, a political commentator for The Australian, became the first Australian journalist to visit Nauru in over 18 months. While on the island, Kenny interviewed a Somalian refugee known as "Abyan", who alleged she had been raped on Nauru and requested an abortion of the resulting pregnancy. Pamela Curr of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre accused Kenny of forcing his way into Abyan's quarters to speak to her—a claim Kenny strongly denied.[56] In June 2016, the Press Council of Australia dismissed a complaint regarding the wording of his article and its headline.[62]

In June 2016, a television crew from A Current Affair was granted access to the island and the centre. Reporter Caroline Marcus presented asylum seekers housed in fully equipped demountable units, and provided with their own television, microwave, airconditioning units and refrigerator. In a column in The Daily Telegraph and an interview with ACA host Tracy Grimshaw, Marcus denied that there were any conditions on the crew's visit, and stated that the Australian government had been unaware of the crew being granted visas until after they had arrived on the island.[63]

See also

- Asylum in Australia

- Manus Regional Processing Centre

- List of Australian immigration detention facilities

- Operation Sovereign Borders

- Pacific solution

- PNG solution

- Immigrant health in Australia

References

- ^ Medhora, Shalailah (6 November 2015). "Julia Gillard defends hardline asylum seeker policy in al-Jazeera interview". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Tony Abbott pushes for Nauru asylum seeker option on visit to island". news.com.au. HeraldSun,AAP. 12 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Phillips, Janet (28 February 2014). "A comparison of Coalition and Labor government asylum policies in Australia since 2001". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Australia's offshore processing of asylum seekers in Nauru and PNG: a quick guide to statistics and resources". Parliament of Australia. 19 December 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Amin, Mridula; Kwai, Isabella (5 November 2018). "The Nauru Experience: Zero-Tolerance Immigration and Suicidal Children". New York Times. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Final four children held on Nauru to be resettled with their families in US". The Guardian. 3 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "Operation Sovereign Borders monthly update: March 2019 - Australian Border Force Newsroom". newsroom.abf.gov.au. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b Armbruster, Stefan (21 May 2020). "Dozens of refugees flown from Australia and PNG to US despite coronavirus travel bans". SBS News. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Oxfam (February 2002). "Adrift in the Pacific: The Implications of Australia's Pacific Refugee Solution" (PDF). Oxfam: 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dobell, Graeme; Downer, Alexander (11 December 2001). "Nauru: holiday camp or asylum hell?". PM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 February 2007.

- ^ Frysinger, Galen R. (16 July 2004). "Sketch map of Nauru". Archived from the original on 16 July 2004. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ Bartlett, Andrew (7 August 2003). "Government-sponsored child abuse at the Nauru detention centres". On Line Opinion.

- ^ Cloutier, Bernard (1998). "Nauru". Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ Kneebone, Susan; Felicity Rawlings-Sanaei (2007). New Regionalism and Asylum Seekers: Challenges Ahead. Berghahn Books. p. 180. ISBN 1845453441. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "N A U R U". Nauruwire.org. 31 January 1968. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ (30 September 2006) Samantha Hawley. Burmese asylum seekers likely to achieve refugee status. AM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Asylum seekers to be sent to Nauru". ABC Online News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ « Pacific solution ends but tough stance to remain », Craig Skehan, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 2007

- ^ « Burmese detainees granted asylum » Archived 11 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Cath Hart, The Australian, 10 December 2007

- ^ « Nauru fears gap when camps close », The Age, 11 December 2007

- ^ "Memorandum of Understanding between the Republic of Nauru and the Commonwealth of Australia, relating to the transfer to and assessment of persons in Nauru, and related issues, signed and entered into force 29 August 2012" (PDF). Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Grubel, James Australia reopens asylum detention in Nauru tent city 14 September 2012 Reuters Retrieved 10 October 2015

- ^ a b "Work needed on Nauru detention centre". BigPond News. 19 September 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ (24 August 2012) Ben Packham. UN won't work with Labor on asylum-seeker processing on Nauru and Manus Island. The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Nauru Camp A Human Rights Catastrophe With No End in Sight" (PDF). Amnesty International. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Amnesty International slams Nauru facility". Amnesty International. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 28 December 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Memorandum of Understanding between the Republic of Nauru and the Commonwealth of Australia, relating to the transfer to and assessment of persons in Nauru, and related issues, signed and entered into force 3 August 2013

- ^ a b c "Photos of riot damage at Nauru detention centre released by Department of Immigration". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 21 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "Asylum seekers in police custody after riot at Nauru detention centre". ABC (Australia). 21 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Hall, Bianca; Flitton, Daniel (19 July 2013). "Policeman 'held hostage' as rioting breaks out on Nauru". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ a b Staff (20 July 2013). "Nauru detention centre riot 'biggest, baddest ever'". The Age. AAP. Retrieved 20 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ "Police attend full-scale riot at asylum seeker detention centre on Nauru". ABC (Australia). 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ "Dozens charged after Nauru detention riot". news.com.au. 21 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Allard, Tom Nauru's move to open its detention centre makes it "more dangerous" for asylum seekers October 9, 2015 Sydney Morning Herald Retrieved 10 October 2015

- ^ Anderson, Stephanie; Keany, Francis (13 November 2016). "PM unveils 'one-off' refugee resettlement deal with US". ABC News. Retrieved 4 February 2017.; Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, Factsheet: Australia–United States Resettlement Arrangement, Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ a b Stephanie Anderson and Julie Doyle, 'Nauru and Manus Island refugees yet to be vetted under US-Australia deal', ABC News, 27 March 2017.

- ^ Stephanie Anderson, Francis Keany, 'Malcolm Turnbull, Peter Dutton announce refugee resettlement deal with US', ABC News, 13 November 2016.

- ^ Murphy, Katharine. "Nine facts about the medical evacuation bill". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Kwai, Isabella (12 February 2019). "Australia to Allow Medical Evacuation for Nauru and Manus Island Detainees". New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Procter, Nicholas; Kenny, Mary Anne (13 February 2019). "Explainer: how will the 'medevac' bill actually affect ill asylum seekers?". The Conversation. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Chia, Joyce (27 October 2019). "Offshore processing statistics and Operation Sovereign Borders". Refugee Council of Australia. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Australian Government. Senate. Legal And Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee (21 October 2019). "Estimates" (Document). p. 76.

Proof Committee Hansard

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ a b Helen Davidson (15 November 2018). "Brisbane construction firm Canstruct made $43m profit running Nauru detention centre last year". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Mares, Peter (2002). Borderline: Australia's Treatment of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the Wake of the Tampa. UNSW Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 0868407895. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ "Nauru detainees stitch lips together". ABC News. Australia. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Second refugee at Australian detention centre in Nauru sets herself on fire". The Guardian.

- ^ a b AAP (5 February 2013). "Nurse Marianne Evers likens Nauru detention centre to concentration camp". news.com.au. News Limited. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Gordon, Michael (2007). "The Pacific Solution". In Lusher, Dean; Haslam, Nick (eds.). Yearning to Breathe Free: Seeking Asylum in Australia. Federation Press. p. 79. ISBN 1862876568. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Gordon, Dr. Michael; Gunn, Tobias; Juratowitch, Dr. Rodney; Kenney, Jarrod; Maree, E.; Tacey, Hamish; Vibhakar, Viktoria; et al. (7 April 2015). "An Open Letter to the Australian People". www.aasw.asn.au. Australian Association of Social Workers. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "Nauru workers say govt knew about abuse". skynews.com.au. Australian News Channel Pty. 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Report condemns Nauru detention centre conditions". SBS News. 5 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ correspondent, Heath Aston, political (20 March 2015). "Rapes, sexual assault, drugs for favours in Australia's detention centre on Nauru: independent Moss review". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harrison, Virginia. "Nauru refugees: The island where children have given up on life". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Nauru media visa fee hike to 'cover up harsh conditions at Australian tax-payer funded detention centre'". ABC News. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Exclusive Nauru access for The Australian". Media Watch. ABC. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "PEN International Resolution on Australia" (PDF). PEN International. October 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Australia: Process Kurdish Iranian journalist's asylum claim". PEN International. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "Behrouz Boochani". Refugee Alternatives. 23 January 2017. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "What are the secrecy provisions of the Border Force Act?". ABC News. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Hutchens, Gareth. "Dutton retreats on offshore detention secrecy rules that threaten workers with jail". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Adjudication 1679: Complainant/The Australian (June 2016)". Press Council of Australia. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Schipp, Debbie (21 June 2016). "Inside Nauru: 'You make a nice prison, it's still a prison'". news.com.au. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 22 June 2016.