Pan-American Highway

The Pan-American Highway (Template:Lang-fr; Template:Lang-pt; Template:Lang-es) is a network of roads stretching across the American continents and measuring about 30,000 kilometres (19,000 mi)[1] in total length. Except for a rainforest break of approximately 106 km (70 mi) in northwest Colombia, called the Darién Gap, the roads link almost all of the Pacific coastal countries of the Americas in a connected highway system. According to Guinness World Records, the Pan-American Highway is the world's longest "motorable road". However, because of the Darién Gap, it is not possible to cross between South America and Central America with conventional highway vehicles. Without an all-terrain vehicle, the only way to safely navigate this terrestrial stretch is by sea.

The Pan-American Highway passes through many diverse climates and ecological types – ranging from dense jungles to arid deserts and barren tundra. Some areas are fully passable only during the dry season, and in many regions driving is occasionally hazardous. The Pan-American Highway system is physically mostly complete and extends in de facto terms from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, in North America to the lower reaches of South America. Several southern highway termini are claimed, including the cities of Puerto Montt and Quellón in Chile and Ushuaia in Argentina.

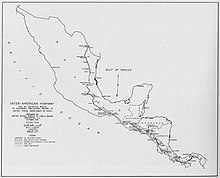

West and north of the Darién Gap, this roadway is also known as the Inter-American Highway through Central America and Mexico. There it splits into several spurs leading to the Mexico–United States border.

Development and construction

The concept of an overland route from one tip of the Americas to the other was originally proposed as a railroad at the First Pan-American Conference in 1889; however, this proposal was never realized. The concept of building a highway emerged at the Fifth International Conference of American States in 1923, after the automobile and other vehicles had begun to replace railroads for both passenger and goods transportation. The first conference regarding construction of the highway occurred on October 5, 1925.

Finally, on July 29, 1937, in the latter years of the Great Depression, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Canada, and the United States signed the Convention on the Pan-American Highway, whereby they agreed to achieve speedy construction, by all adequate means.[2] In 1950, Mexico became the first Latin American country to complete its portion of the highway.[3]

In practice, the concept of the Pan-American Highway is more publicly embraced in Latin American countries than in the United States or Canada. Much of the road system in Latin America is explicitly marked as Pan-American (commonly Vía Panam or Vía Panamericana). In the United States, the entire interstate highway system is official but only the highway numbers are signed. In Canada, there are no official routes at all.

Countries served

The Northern Pan-American Highway travels through 9 countries, including in Central America:

- Canada (Canamex Corridor unofficial)

- United States (interstate highway system official)

- Mexico

- Guatemala

- El Salvador

- Honduras

- Nicaragua

- Costa Rica

- Panama

The Southern Pan-American Highway travels through 5 countries:

Important spurs also connect with 4 other South American countries:

Northern section

Alaska and Canada

The Alaska Highway through Alaska, Yukon and British Columbia is commonly considered a de facto northerly extension of the Pan-American Highway, as is the Dalton Highway in Alaska. In Canada, no particular road has been officially designated as the Pan-American Highway. The National Highway System, which includes but is not limited to the Trans-Canada Highway, is the country's only official inter-provincial highway system. However, several Canadian highways are a natural extension of several key American highways that reach the Canada–US border. British Columbia Highway 97 and Highway 2 to Alberta both pick up where the southern end of the Alaska highway leaves off. Highway 97 becomes U.S. Route 97 at the Canada–US border. British Columbia Highway 99 provides an alternate route from Highway 97 just north of Cache Creek; it runs through Whistler and Vancouver before ending at the Canada–US border at the north end of Interstate 5 in Washington state, the beginning of the official Pan-American route south of British Columbia. Meanwhile, Alberta Highway 2 runs south and east to Alberta Highway 3 leading into Lethbridge, then south on Alberta Highway 4 to the Canada–US border, where it becomes Interstate 15 in Montana. This is the first official stretch of the Pan-American Highway south of the Alberta route, both of which are also part of the CANAMEX Corridor.

Contiguous 48 states of the United States

In 1966, the US Federal Highway Administration designated the entire Interstate Highway System as part of the Pan-American Highway System,[4][5] but this has not been expressed in any of the official interstate signage. Of the many freeways that make up this very comprehensive system, several are notable because of their mainly north-south orientation and their links to the main Mexican route and its spurs, as well as to key routes in Canada that link to the Alaska Highway.

These include the following:

- Interstate 5 runs north from San Diego, California to Blaine, Washington, then links indirectly with British Columbia Highway 97 north of the Canada–US border. A technically direct link between the same interstate and the U.S. Route 97 system can be found near Weed, California. US Route 97 runs northeast then north through Oregon and Washington from this junction, and becomes BC Highway 97 at the border with Canada.

- Interstate 15 links San Diego with Alberta Highway 2 that eventually crosses into British Columbia and ends at the southern terminus of the Alaska Highway. Interstate 8 provides an east-west link from San Diego to Interstate 10 near Phoenix, Arizona. The latter continues to Tucson and links with Interstate 19, which becomes a spur of the Pan-American highway through Mexico at the Nogales border crossing.

- Interstate 25 runs north from Interstate 10 at Las Cruces, New Mexico to Interstate 90 in Wyoming. This route has no direct extension into Canada but links indirectly to Interstate 15. Interstate 25 in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was named the Pan-American Freeway,[6]: 248 as an extension of Highway 45, the Mexican spur linking El Paso to the original route along highway 85 north of Mexico City.[7] This portion of I-25 largely follows the historic Camino Real, and thus serves a culturally significant portion of the Pan American system. Like I-15, the complete route of Interstate 25 is an official northerly continuation toward Alberta, where Highway 2 provides a direct but unofficial Canadian link to the Alaska Highway.

- Interstate 35 is a northerly continuation of the original Pan-American highway following Mexican Federal Highway 85. It extends from Laredo, Texas to the Canada–United States border north of Duluth, Minnesota with a spur, Interstate 29, that leads farther west toward Winnipeg, Manitoba. The section of Interstate 35 in San Antonio, Texas is referred to as the Pan Am Expressway by locals. I-35 is a northerly continuation of Mexico Highway 85, the original official Mexican route, ending in Duluth, Minnesota, where Minnesota State Highway 61 continues to the Canada–US border near Thunder Bay, Ontario. The Trans-Canada Highway provides a link from Winnipeg and Thunder Bay to Alberta and the Alaska Highway, but it is not officially part of the Pan-American Highway.

- An additional route only partially complete is Interstate 69, which will eventually run northeasterly from the same Laredo border crossing to the Windsor-Quebec City Corridor in Canada, where the route becomes unofficial.

Related North American highways

Several North American routes have names that make no direct reference to the Pan-American Highway, in part because some sections follow highways that are not up to full freeway standard.

- The CANAMEX Corridor is designated from Mexico City to the western United States from Arizona to Montana,[8] and continues north into western Canada. Although lacking any official status for the Pan American Highway in Canada, this is the only official North American highway that runs through Canada, the U.S., and Mexico to link the Alaska Highway with the Pan-American Highway at Mexico City. Unlike corresponding Pan American routes in the American southwest, the Canamex Highway bypasses San Diego by using several non-interstate highways to provide a shortcut from I-15 at Las Vegas, Nevada to I-10 at Phoenix, Arizona for traffic accessing I-15 from the Nogales border crossing.

- The CanAm Highway follows Interstate 25 from El Paso to U.S. Route 85 north of Denver, Colorado, then continues into the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, following parts of provincial highways 35, 39, 6, 3, and 2 in succession before terminating at La Ronge. This route was first proposed during the 1920s but was never properly promoted nor developed. A section of the CanAm in southern Saskatchewan has deteriorated to the point where it is no longer a paved highway.[9]

- The NAFTA Superhighway tag has been unofficially used in connection with Interstate 35 from Laredo, Texas to the Canadian border; there it downgrades to a non-freeway route ending at Thunder Bay, Ontario. A spur follows Interstate 29 to the border, where it also downgrades to an arterial highway that extends to Winnipeg, Manitoba. The NAFTA highway sometimes unofficially includes Interstate 69, which is mostly complete from western Kentucky to the Canada–US border at Port Huron, Michigan. In Canada, Ontario Highway 402 and other freeways in the Windsor-Quebec City Corridor can be considered a northeastward extension of this version of the NAFTA superhighway. To the southwest, from western Kentucky to the Mexican border, there is no single superhighway yet completed. Pending completion of I-69, the main highway links to Mexico follow parts of US routes 45 and 51 from Kentucky to western Tennessee, I-155 into Missouri, parts of Interstates 55 and 40 from Missouri to Arkansas, and I-30 to the Texas stretch of I-35 that continues to the Mexican border at Laredo, Texas. The section of I-69 to be completed south of Kentucky is expected eventually to continue southwestward to the Texas Gulf Coast. It will have a spur linking to the original Pan-American route through Mexico to Laredo, and additional branches extending to the Mexican spurs that cross the border at Pharr, Texas, and Brownsville, Texas.

Mexico

The official route of the Pan-American Highway through Mexico (where it is known as the Inter-American Highway) starts at Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas (opposite Laredo, Texas) and goes south to Mexico City along Mexican Federal Highway 85.[citation needed] Later branches were built to the border as follows:

- Nogales spur – Mexican Federal Highway 15 from Mexico City

- El Paso spur – Mexican Federal Highway 45 from Highway 85 north of Mexico City to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua

- Eagle Pass spur – unknown, possibly Mexican Federal Highway 57 from Mexico City to Piedras Negras, Coahuila

- Pharr spur – Mexican Federal Highway 40 from Monterrey to Reynosa, Tamaulipas

- Brownsville spur – Mexican Federal Highway 101 from Ciudad Victoria to Matamoros, Tamaulipas

From Mexico City to the border with Guatemala, the highway follows Mexican Federal Highway 190.[10][11][12]

Central America

The Pan-American (or Inter-American) highway passes through the Central American countries with the highway designation of CA-1 (Central American Highway 1). In Guatemala, it passes through 10 departments, including The Department Of Guatemala, where it passes through Guatemala City. In El Salvador, it passes through the cities of Santa Ana, Santa Tecla, Antiguo Cuscatlán, San Salvador, San Martín, San Miguel, and crosses the border into Honduras at Amatillo. From Honduras, it passes into Nicaragua, passing through the Nicaraguan cities of Somoto, Estelí, Sebaco, Managua, Jinotepe, and Rivas before entering Costa Rica at Peñas Blancas. In Costa Rica, it passes through Liberia, San José, Cartago, Pérez Zeledón, Palmares, Neily, before crossing into Panama at Paso Canoas. In Panama, it crosses the Panama Canal via the Centennial Bridge, and ends at Yaviza, at the edge of the Darién Gap. The road had formerly ended at Cañita, Panama, 180 km (110 mi) north of its current end. United States government funding was particularly significant to complete the high-level Bridge of the Americas over the Panama Canal, during the years when the canal was administered by the United States.

Belize was supposedly included in the route at one time, after it switched to driving on the right. Prior to independence, as British Honduras, it was the only Central American country to drive on the left side of the road.

Darién Gap

The Pan-American Highway is interrupted between Panama and Colombia by a 106 km (70 mi) stretch of marshland known as the Darién Gap. The highway terminates at Turbo, Colombia and Yaviza, Panama. Because of swamps, marshes, and rivers, construction would be very expensive.

Efforts have been made for decades to eliminate the gap in the Pan-American highway, but have been controversial. Planning began in 1971 with the help of United States funding, but this was halted in 1974 after concerns raised by environmentalists. Another effort to build the road began in 1992, but by 1994 a United Nations agency reported that the road, and the subsequent development, would cause extensive environmental damage. The Embera-Wounaan and Kuna have also expressed concern that the road could bring about the potential erosion of their cultures.

The Darién Gap has challenged adventurers for many years. A 1962 expedition with three Chevrolet Corvair rear-engine cars [and two support trucks] completed the trip south [from Chicago] through to the Colombian border.[13] A 1971-72 British expedition from Alaska to Argentina attempted to transit the Gap with two standard production Range Rovers, supported by a team of Land Rovers. They barely succeeded in thrashing a passage through the extreme terrain.[14] In 1979 a team led by Mark Smith drove standard production CJ7-model Jeeps from South to North, traversing the Gap - with difficulty.[15] In June 1984, Loren and Patty Upton took 741 days slogging, winching, chopping and digging their way through the inhospitable jungles of the Darién Gap.

One proposed option to bridge the gap is a short ferry link from Colombia to a new ferry port in Panama,[16] with an extension of the existing Panama highway that would complete the highway without violating these environmental concerns. However, past attempts to operate such a service have ended in failure.

Southern section

Colombia and Venezuela

The southern part of the highway begins in Turbo, Colombia, from where it follows Colombia Highway 62 to Medellín. At Medellín, Colombia Highway 56 leads to Bogotá, but Colombia Highway 25 turns south for a more direct route. Colombia Highway 40 is routed southwest from Bogotá to join Highway 25 at Zarzal. Highway 25 continues all the way to the border with Ecuador.

Another route, known as the Simón Bolívar Highway, runs from Bogotá (Colombia) to Guaira (Venezuela). It begins by using Colombia Highways 55 & 66 all the way to the border with Venezuela. From there it uses Venezuela Highway 1 to Caracas and Venezuela Highway 9 to its end at Guaira.

Peru, Ecuador and Chile

Ecuador Highway 35 runs the whole length of that country. Peru Highway 1 carries the Pan-American Highway all the way through Peru to the border with Chile.

In Chile, the highway follows Chile Route 5 south to a point north of Santiago (Llaillay), where the highway splits into two parts, one of which goes through Chilean territory to Puerto Montt, where it splits again, to Quellón on Chiloé Island, and to its continuation as the Carretera Austral. The other part goes east along Chile Route 60.

Argentina and Paraguay

In Argentina it begins on the Argentina National Route 7 and continues to Buenos Aires, the end of the main highway.[17] The highway network also continues south of Buenos Aires along Argentina National Route 3 towards the city of Ushuaia in Tierra del Fuego. Another branch, from Buenos Aires to Asunción in Paraguay, heads out of Buenos Aires on Argentina National Route 9. It switches to Argentina National Route 11 at Rosario, which crosses the border with Paraguay right at Asunción. Other branches probably exist across the center of South America.

Brazil and Uruguay

A continuation of the Pan-American Highway to the Brazilian cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro uses a ferry from Buenos Aires to Colonia in Uruguay and Uruguay Highway 1 to Montevideo. Uruguay Highway 9 and Brazil Highway 471 route to near Pelotas, from where Brazil Highway 116 leads to Brazilian main cities.

Guyana, Suriname and French Guyana

The highway does not have official segments to Belize, Guyana, Suriname (there known in Template:Lang-nl) and French Guiana, nor to any of the island nations in the Americas. However, highways from Venezuela link to Brazilian Trans-Amazonian highway that provides a southwest entrance to Guyana, route to the coast, and follow a coastal route through Suriname to French Guiana.

West Indies section

Plans have been discussed for including the West Indies in the Pan American Highway system. According to these, a system of ferries would be established to connect terminal points of the highway. Travelers would then be able to ferry from Key West to Havana, drive to the eastern tip of Cuba, ferry to Haiti, drive through Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and ferry again to Puerto Rico. Included in this system would also be a ferry from the western tip of Cuba to the Yucatán Peninsula. Mexico has already surveyed a route which will run across the Yucatán, Campeche, and Chiapas to San Cristobal de Las Casas, on the Pan American Highway. ("The Pan American Highway System" by Travel Division Pan American Union, Washington D.C. October 1947)

Art and culture

Travel writer Tim Cahill wrote a book, Road Fever, about his record-setting 24-day drive from Ushuaia in the Argentine province of Tierra del Fuego to Prudhoe Bay in the U.S. state of Alaska with professional long-distance driver Garry Sowerby, much of their route following the Pan-American Highway.[18]

In the British motoring show Top Gear, the presenters drove on a section of the road in their off-road vehicles in the Bolivian Special.

In 2003, Kevin Sanders, a long-distance rider, broke the Guinness World Record for the fastest traversal of the highway by motorcycle in 34 days.[19]

In 2018, a British cyclist named Dean Stott who had planned on riding the length of the Americas in 110 days to set a new Guinness World Record ended up completing the 14,000-mile journey in just under 100 days after learning that he and his wife had been invited to the royal wedding, revealing that he would have missed the event had he stuck to his original schedule.[20]

Photo gallery

-

The northern end of the Pan-American Highway at Deadhorse, Alaska, USA

-

Interstate 25 (Pan-American Freeway) approaching the Big I interchange in Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA

-

Pan-American Highway through San Martin, El Salvador.

-

Another view of the Pan-American Highway in El Salvador.

-

Pan-American Highway in El Salvador between Lourdes and Santa Ana; this flat 1.5 km (0.93 mi) long straight section can be used as an airstrip and it was used during El Salvador Civil War.

-

Highway in Guanacaste, Costa Rica (going towards the Nicaraguan border, still many kilometres away.)

-

Pan-American Highway in Tres Rios, Costa Rica, right before the toll plaza (about 337 more km / 209 more mi to go until the Panamanian border).

-

Highway, at the border of Costa Rica and Panama

-

Panamericana – Pan American Highway – in Pichincha, Ecuador, near Cashapamba

-

Panamericana – northern Peru near Pacasmayo

-

Pan American Highway near Pisco (Peru)

-

Panamericana near Puerto De Lomas, Peru

-

Panamericana in the Atacama Desert northern Chile

-

Chevy Suburban traveled all of the Pan-American Highway. Patagonia, Chile.

See also

- CANAMEX Corridor

- NAFTA superhighway

- Continental 1

- Asian Highway Network

- Trans-Siberian Highway

- Buenos Aires

References

- ^ "A Gap in the Andes : Image of the Day". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ Text of the Convention.

- ^ "Highway Run". Harper's: 70–80. July 2006.

- ^ American Automobile Association, American Motorist, ca. 1974

- ^ New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department, State of New Mexico Memorial Designations and Dedications of Highways, Structures and Buildings Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2007, p. 14

- ^ Bryan, Howard (1989). Albuquerque Remembered. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826337825. OCLC 62109913. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "Datos Viales de Hidalgo" (PDF) (in Spanish). Dirección General de Servicios Técnicos, Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes. 2011. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ "Federal Definition". Canamex coalition. Archived from the original on 2008-01-10.

- ^ "'Super corridor' theories simply updated old idea". The Star Phoenix. August 28, 2007. Archived from the original on March 1, 2015. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ "Datos Viales de Puebla" (PDF) (in Spanish). Dirección General de Servicios Técnicos, Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes. 2011. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ "Cruce fronterizo vehicular formal: Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, México — La Mesilla, Guatemala" (PDF) (in Spanish). Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2012-04-06.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "República de Guatemala – Red Vial con Distancias" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Geografico National (IGN); Ministerio de Comunicaciones Infraestructura y Vivienda (CIV). 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- ^ Lenny Clairmont (21 February 2016). "Daring The Darien" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Range Rover Darien Gap - Range Rover Classic".

- ^ MotorTrend Channel (12 May 2015). "The Greatest Jeep Adventure Ever! Mark Smith & The Darien Gap - Dirt Every Day Ep. 39" – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Coming Era of Mega Systems, Part 1 – Transportation". DaVinci Institute – Futurist Speaker. 2014-12-16. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Pan-American Highway – MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Cahill, Tim (1992). Road Fever. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-394-75837-4.

- ^ Walker, Tim (29 September 2005). "How to have a real adventure: Take a train or get on a bike to experience the thrill of travel as it used to be". The Independent (UK). Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "British cyclist smashes Pan American Highway record after learning of royal wedding invitation". road.cc. 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

Sources

- Plan Federal Highway System, New York Times May 15, 1932 page XX7

- Reported from the Motor World, New York Times January 26, 1936 page XX6

- Hemisphere Road is Nearer Reality, New York Times January 7, 1953 page 58

- 1997–98 AAA Caribbean, Central America and South America map

- Popular Mechanics, March 1943, Longest Road In The World

Further reading

- Rutkow, Eric (2019). The Longest Line on the Map: The United States, the Pan-American Highway, and the Quest to Link the Americas. Scribner. ISBN 9781501103926.

External links

Pan-American Highway travel guide from Wikivoyage

Pan-American Highway travel guide from Wikivoyage Geographic data related to Pan-American Highway at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Pan-American Highway at OpenStreetMap