Robert de Stretton

Robert de Stretton | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield | |

| Archdiocese | Province of Canterbury |

| Elected | 30 November 1358 |

| Term ended | 28 March 1385 |

| Predecessor | Roger Northburgh |

| Successor | Walter Skirlaw |

| Previous post(s) | Confessor to Edward, the Black Prince |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | before May 1349 |

| Consecration | 27 September 1360 by Michael Northburgh, Bishop of London, John Sheppey, Bishop of Rochester |

| Personal details | |

| Born | |

| Died | 28 March 1385 Haywood manor, Staffordshire |

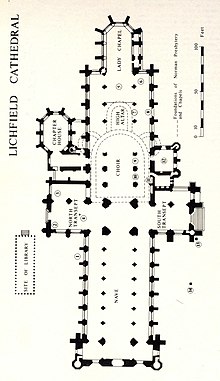

| Buried | St Andrew's Chapel, Lichfield Cathedral |

| Denomination | Catholic |

Robert de Stretton (died 1385) was Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield following the death of Roger Northburgh in 1358.[1] A client of Edward, the Black Prince, he became a "notorious figure"[2] because it was alleged that he was illiterate, although this is now largely discounted as unlikely, as he was a relatively efficient administrator.[3]

Origins

Robert de Stretton is presumed[3] to have been born at Great Stretton or Stretton Magna in Leicestershire, a village that has since disappeared,[4] although neighbouring Little Stretton survives. His parents were Robert Eyryk and his wife Johanna.[5] He is thought to have had three siblings: Sir William Eyryk, the heir to the family estates, John and Adelina. Fletcher considered that Sir William was the ancestor of a prominent Leicestershire landowning family, the Heyricks of Houghton on the Hill, but this is far from certain.[3] Families called Heyrick, and later Herrick, were to influential in Leicester and Leicestershire for centuries.[6] When Robert's chantry at Stretton was dissolved in the 16th century, the dissolution certificate referred to him as "Robert Heyrick, sometym byshoppe of Chester"[7] and it seems clear that he was frequently known by this name, although "de Stretton" was his more usual surname. The name is derived from the Danish personal name Eirik and suggests Norse origins.[8] It was found in a number of Leicestershire villages.

The relationship between the Eyryk family and Great Stretton is problematic. Fletcher claimed that the Eyryk family were "undoubtedly seated at Stretton Magna at an early date, and held land there under Leicester Abbey,"[9] providing a family tree, based on research by Nichols, that pushed the connection back to the reign of Henry III (1216-1272), while the recent Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article asserts that Robert himself held the manor in the 1370s. The relevant Victoria County History volumes provides only limited corroboration, showing the pattern of land holding at Great Stretton as complicated: there was a high degree of subinfeudation by the late 13th century.[10] and in the 14th century, the manor itself was held by the Zouche family of Haryngworth from the Ferrers of Groby. The Heyrick family were substantial free tenants and the most important residents,[8] but not apparently lords of the manor. Their presence in the village was first attested in 1274, with one Richard Heirick, a cleric. In 1327 and 1332 they paid about a third of the village's total tax bill, giving an indication of their relative importance. Bishop Robert inherited some of the family's land at Great Stretton in later life.

Career

Early appointments

The existence of the clerk Richard Heirick in the late 13th century makes clear that the Eyryks, like many other lower landed gentry families, were accustomed to some of their young men seeking ordination. However, nothing is known of how Robert de Stretton adopted this career path or of his education and clerical formation.[3] Fletcher, in his earlier biography, asserted that he "became Doctor of Laws, one of the auditors of the Rota in the Court of Rome and Chaplain to Edward the Black Prince"[11] - the academic claim derived from Henry Wharton's Anglia Sacra.[12] He had moderated the certainty of his claims for Stretton's academic achievements by the time he wrote his Dictionary of National Biography article.[13] The recent Oxford edition discounts them as mistaken, allowing only that he was sometimes addressed as "Master" but no specific degree named.[3] However, there is no doubt that he did become a client of Edward, the Prince of Wales, probably in the early 1340s. By March 1347 he was serving the prince as almoner – an important but essentially administrative office which might have been occupied by a deacon or one in minor orders. By May 1349, however, he was the prince's confessor – a function for which ordination to the priesthood was prerequisite.

Royal service brought Stretton numerous lucrative preferments. By 1343 he was already rector of Wigston, close to his home village, and in that year became a canon of Chichester Cathedral, being appointed to the prebend of Waltham.[14] On 25 January 1344 the prince had him appointed precentor of St Asaph Cathedral, a post to which was attached the prebend of Faenol[15] Another Welsh appointment came on 28 March 1347 with a canonry at Llandaff Cathedral and the prebend of Caerau[16] At some time he also became a canon of Lincoln Cathedral with the prebend Sanctae Crucis (of Holy Cross) at Spaldwick.[17] He also received appointments at Gnosall in Staffordshire, in London and at Salisbury.[3] By 1354[13] he was rector of Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion, in the Diocese of St David's.

Fletcher thought that he was already also a canon at Lichfield before he became bishop,[13] specifying collation to the prebend of Pipa Parva in 1358. Swanson thinks this mistaken, despite the testimony of a papal bull of 1360.[3] Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae records the royal grant of Pipa Parva to M. Robert de Stretton on 29 November 1358[18] but this was only the day before Stretton was elected bishop.[19] This Master Robert de Stretton was appointed to positions in the diocese on several occasions while Stretton was bishop: after serving as Archdeacon of Derby from 1361 to 1369, he exchanged the post for the Archdeaconry of Coventry,[20] where he served until 1408.[21] As he cannot have been the bishop, he was a namesake and probably a relative.

Stretton was also engaged in political matters. In 1347 he was one of the envoys who sought unsuccessfully to arrange a marriage between the Black Prince and a daughter of Afonso I of Portugal.[3] From 1350 he was employed as a king's clerk. In 1355 the French Pope Innocent VI, resident at Avignon, tried to bring about a truce in the Hundred Year's War. Two nuncios were sent to promote talks between the James of Bourbon, the Constable of France and Edward III of England, with a view to averting hostilities in Gascony,[22] where the Black Prince had been conducting a hugely destructive chevauchée. Robert de Stretton, addressed as canon of Lincoln, was one of an English deputation nominated by the Pope to support the nuncios in their mission. However, the peace effort came to nothing and de Stretton's master followed up his campaign with another devastating raid the following year, which led to the Battle of Poitiers.

Consecration as bishop

The process by which Robert de Stretton became Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield was, and remains, controversial. He was canonically elected to the see, with the support of the Black Prince, on 30 November 1358.[19] Although royal assent was granted on 21 January 1359, his consecration was delayed almost 22 months — until 27 September 1360. G. R. Owst, pioneering historian of preaching in the period, fell upon Stretton's case with glee, as confirming some of the most damning allegations about clerical incompetence made by contemporary preachers:

- Rejected for his utter illiteracy by the Bishop of Rochester, by papal examiners at Avignon, and again by the English Primate, after as many re-examinations more in the effort to promote him to the see of Coventry and Lichfield, nevertheless he triumphed in the end."[2]

This judgement largely, if tendentiously, reflected Fletcher's narrative. This is mainly based on the Vitae archiepiscoporum Cantuariensium, a 14th-century work attributed to Stephen Birchington, which became established as the key narrative because it was reproduced by Henry Wharton, a highly respected 17th century historian and bibliographer. The Vitae asserts that Stretton was summoned before the Curia because of rumours of his illiteracy had reached Pope Innocent. After examination, he was propter defectum literaturae repulsi – rejected on account of a failure in letters.[23] As Stretton remained the royal candidate, the Pope sought a tactful way out of the dilemma by ordering the Archbishop of Rochester and Bishop of Rochester to examine him further. This version of events then has the Church bullied, despite further failures on Stretton's part, into conceding his consecration, a papal bull forcing Simon Islip, the Archbishop of Canterbury, to depute the task to the Bishops of London and Rochester, which they performed "with evident reluctance."[24]

More recently, Swanson has cast doubt on the entire story of the appeal to Rome and the examination before the Curia, which is not corroborated in other sources.[3] The papal bull of 22 April 1360 merely says that Stretton was forced to plead his case because he had allowed himself to be elected without realising that the Pope had reserved the see of Coventry and Lichfield. As there was now no longer any question of another candidate, Islip was deputed to carry out the consecration, unless he preferred the Bishop of London to act for him. Without the story of the failed literacy examination before the Curia, this appears a straightforward case of administrative confusion and delay. Islip acted on the Pope's instructions and left the consecration of Stretton to Michael Northburgh, the Bishop of London and his predecessor's nephew, and John Sheppey, the Bishop of Rochester. Swanson denies that there is any evidence of reluctance to consecrate Stretton.

The profession of canonical obedience to Canterbury took place at Lambeth Palace on 5 February 1361,[19] alio professionem legente, quod ipse legere non posset – "another reading the profession, for he could not read it himself." Fletcher commented on this: "It is difficult to conceive such a degree of ignorance in a prelate, but the words of the register are conclusive."[13] However, the more recent view is that Stretton was already suffering from the sight defect that would later leave him completely blind.[3] Wharton included in Anglia Sacra a continuation of the history of Lichfield by William Whitlocke, which describes Stretton as eximius vir – an exceptional man – and goes on to make the probably exaggerated claims for his attainments in jurisprudence noted above.[12] It seems that there was always an alternative view of Stretton as a man of some accomplishment, and this certainly fits better with his previous and subsequent records.

Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield

Stretton administered his diocese in a "straightforward and efficient" way.[3] His episcopate was relatively uneventful in turbulent times. The Church was faced by major challenges in the aftermath of the Black Death and in the face of further, briefer outbreaks of the plague, which brought about a high mortality rate and rapid displacement of clergy.[24] Stretton's two registers are particular meticulous and full of detail, suggesting a serious attempt to stabilise the administration. It seems that he was most often resident at the manor of Haywood in Staffordshire, where he died, and the focus of his episcopal activities seems to have been Lichfield Cathedral, the centre of the cult of St Chad, although the diocese had important centres also at Coventry and Chester. Fletcher noted that an unusual number of his ordinations were held at Colwich, which is very close to Haywood.

It is possible occasional friction disturbed the generally friendly relations between the Bishop and his cathedral chapter. A serious problem for 14th century bishops was that the major offices at the cathedral, which should have provided the core episcopal staff, were largely filled by absentees.[25] This was the result of the growth of papal provision to important offices – precisely the issue that seems to have impeded Stretton's own appointment. Deans were generally absent: the Dean of Lichfield from 1371 to 1378, for example, was an Italian bishop, Francis de Teobaldeschi, who was probably Cardinal priest of Santa Sabina.[26] The Treasurer since 1348 and throughout Stretton's first decade was Hugh Pelegrini,[27] a papal nuncio,[22] and therefore another absentee.[25] He lost his position and its emoluments in a royal purge of foreign clergy in 1370, but the campaign was short-lived. Chancellors were absentees from 1364: from 1380 the post was used to reward another Italian bishop, Pileus de Prata, Cardinal priest of Santa Prassede.[28]

Stretton was fortunate in having a cadre of able canons who served the cathedral and diocese reliably over decades, partly filling the administrative gap. Hugh of Hopwas, presumably a local man, was a fellow client of the Black Prince:[25] he became a canon in 1352,[29] well before Stretton's election, in which he must have participated. In 1363 he exchanged the far-flung prebend of Dernford in Cambridgeshire for that of Curborough, close to Lichfield.[30] He served almost throughout Stretton's epicopate, dying in 1384. Richard de Birmingham, official of Bishop Stretton and an effective member of the chapter for 20 years,[25] held the prebend of Pipa Minor[31] and was Archdeacon of Coventry in the 1360s. Stretton had important legal help in the 1370s from John of Merton, a Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge, who was able to act for the diocese in the Court of Arches,[25] the chief ecclesiastical court of the Province of Canterbury. However, much of the work of the cathedral and diocese was done by vicars, essentially clerics hired to deputise for the chapter, who received "commons" or subsistence allowance of 1½d. per day. They began to agitate for a pay rise as early as 1361, citing inflation as a justification. They finally won an increase to 3d. In 1374, but with the proviso that they find a dining room of their own, away from the canons.

Stretton was involved in at least two controversial appointments of note. In 1362 he confirmed the election of Maud or Matilda Botetourt as Abbess of Polesworth Abbey in Warwickshire, despite her being only 20 years old and so under the requisite age,[32] and forbade further reference to the issue.[24] However, Maud must have been exceptional in either ability or connections, as she was to be granted a papal dispensation from obedience to episcopal authority in 1399.[32] The issues at Shrewsbury in the 1374 certainly included family connections, as the problematic appointment was of a Master Robert de Stretton as Dean of St Chad's Church.[33] It seems he had been appointed in 1374 by the Bishop, almost certainly a kinsman. However, the king, who had asserted his rights to what he claimed as a royal chapel in 1344,[34] contested the appointment. The Bishop made no change and was summoned to answer for his contempt, but it seems that his dean was not removed, although the details are unclear.

The most disturbing incident in government of the diocese came in 1364, during a canonical visitation of Derbyshire. For reasons unknown – or, at least, not disclosed in Stretton's register – a large body of heavily armed townspeople attacked his entourage while he was conducting an inspection of Repton Priory. They first surrounded the priory but at 11 pm broke into the premises and terrorised Stretton and his staff for two hours, shooting arrows through the windows of the rooms where they sheltered.[35] Two of the local landed gentry arrived and patched up a truce. Stretton pronounced excommunication on the culprits and then fled north to Alfreton, where he interdicted the town of Repton and St. Wystan's, the parish church. An extant but undated petition of Edward III's reign, complaining of unpunished threatening behaviour and arson by Augustinian canons from the priory, may provide an explanation of the townspeople's revolt against the Church authorities. As the advowson and tithes of the parish church belonged to the priory, it was probably a focus for discontent. The incident perhaps stemmed from a demonstration against the priory that escaped control rather than an assault on Stretton's episcopal authority.

Stretton continued the work of his predecessors in maintaining Lichfield Cathedral as a centre of pilgrimage. Early in the century, Bishop Walter Langton had ordered an expensive new shrine for St Chad from Paris.[36] It was installed in a temporary position, between the High Altar and the unfinished Lady Chapel. In 1378, with the work complete, Stretton had the shrine moved to its final position — probably on a marble table next to the Lady Chapel. On 4 September that year he established a chantry for himself in the chapel of St Giles at Great Stretton – a project envisaged as early as 1350.[3] He endowed it with 8 virgates of land and a wide range of domestic properties and meadows.[37] Ralph, the first chaplain, was to pray for Stretton and for his soul after death, as well as for the souls of Edward III, the Black Prince and a number of Stretton family members. Earlier opinion held that the chantry was in a separate building in a moated area about 200 metres from the parish church,[38] but it is now thought this was mistaken and that the chantry was within the church building.[4]

By this time Stretton's health was failing. He was absent from parliament from 1376 and had become completely blind by September 1381, when the prior and chapter of Canterbury (there being no archbishop) ordered him to appoint a Coadjutor bishop.

Death

Stretton died on 28 January 1381[19] at the manor of Haywood – an episcopal residence[39] in Cannock Chase, north-west of Lichfield. He had requested burial in a previously prepared place near the shrine of St Chad and so was interred in St Andrew's chapel.[40]

Stretton's will was made on 19 March, nine days before his death. It was published for the first time, in translation, by Fletcher (1887).[41] Disclaiming any desire for funeral pomp, Stretton nevertheless left the very large sum of £100 for funeral expenses and a generous 50 marks for distribution to the poor. Most of the bequests were of liturgical items: his mitre and pastoral staff to his successor; his second best missal, osculatorium (a tablet designed to take the kiss of peace), and best chalice and paten, both gilt, the altar of St Chad in Lichfield Cathedral; vestments and crucifix to the High Altar; more vestments for Coventry Cathedral, Pipewell Abbey in Northamptonshire, the Priory of St. Thomas near Stafford; and to his own chantry at Great Stretton a substantial collection of vestments, silver chalice and paten, missal and thurible. The executors included Richard de Birmingham, William de Neuhagh, the Precentor,[42] Richard de Toppeclyve, the Archdeacon of Stafford, and John de Stretton, a canon of St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury. The will was proved on 10 April 1385 and the executors discharged on 8 November 1386.

Notes

- ^ Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 105

- ^ a b Owst, p.36

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Swanson, R. N. "Stretton , Robert (d. 1385)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26662. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b “Great Glen – Great Stretton” in Lee and McKinley

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 198

- ^ Nichols, p. 1

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 206

- ^ a b “Great Glen – Great Stretton: economic history” in Lee and McKinley

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 199

- ^ “Great Glen – Great Stretton: manor” in Lee and McKinley

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 200

- ^ a b Wharton, p. 449

- ^ a b c d Fletcher, William George Dimock (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ “Prebendaries: Waltham” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 7, Chichester Diocese

- ^ “Precentors of St Asaph” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 11, the Welsh Dioceses (Bangor, Llandaff, St Asaph, St Davids)

- ^ “Prebendaries: Caerau” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 11, the Welsh Dioceses (Bangor, Llandaff, St Asaph, St Davids)

- ^ “Prebendaries: Sanctae Crucis or Spaldwick” in "Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 1, Lincoln Diocese"

- ^ “Prebendaries: Pipa Parva” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ a b c d “Bishops of Coventry and Lichfield” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ “Archdeacons: Derby” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ “Archdeacons: Coventry” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ a b Regesta 237: 1355 in Bliss and Johnson

- ^ Wharton, p. 44

- ^ a b c Fletcher (1887), p. 201

- ^ a b c d e Baugh et al. “House of secular canons - Lichfield cathedral: To the Reformation – The fourteenth century” in Greenslade and Pugh (eds) (1970). A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 3

- ^ “Deans of Lichfield” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ “Treasurers of Lichfield” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ “Chancellors of Lichfield” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ "Prebendaries: Derford" in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ “Prebendaries: Curborough” in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ "Prebendaries: Pipa Minor or Prees" in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

- ^ a b “Houses of Benedictine nuns: Abbey of Polesworth” in Page (1908). A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 2

- ^ Owen and Blakeway, p. 197-8

- ^ Owen and Blakeway, p. 185-6

- ^ “Houses of Austin canons: The priory of Repton, with the cell of Calke” in Page: A History of the County of Derby: Volume 2, p. 58-63

- ^ “Lichfield: The cathedral - St. Chad's shrine” in Greenslade: A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14, p. 47-57

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 202

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 207

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 203

- ^ “Lichfield: The cathedral – Burials and monuments” in Greenslade: A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14, p. 47-57

- ^ Fletcher (1887), p. 204-5

- ^ "Precentors of Lichfield" in Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese

References

- Bliss, W.H.; Johnson, C. (1897). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 3, 1342-1362. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Fletcher, William George Dimock (1887). “Robert de Stretton, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, 1360 to 1385” in Associated Architectural Society's Reports and Papers, Volume 19, pp. 198–208, accessed 16 January 2015 at Internet Archive.

Fletcher, William George Dimock (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Greenslade, M.W.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1970). A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 3. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Greenslade, M.W. (1990). A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14, Lichfield. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Hor, Joyce M. (1964). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 7, Chichester Diocese. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Jones, B. (1964). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Jones, B. (1965). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 11, the Welsh Dioceses (Bangor, Llandaff, St Asaph, St Davids). Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Jones, B. (1964). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 1, Lincoln Diocese. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Lee, J.M., McKinley, R.A. (1964). A History of the County of Leicestershire: Volume 5, Gartree Hundred. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nichols, John Gough (1860). The Heyricke Letters. Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Owen, Hugh and Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury, Volume 2, Harding and Lepard, London, accessed 22 January 2015 at Internet Archive.

- Owst, G. R. (1926). Preaching in Medieval England. Cambridge University Press.

- Page, William (1907). A History of the County of Derby: Volume 2. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Page, William (1908). A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 2. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Swanson, R. N. "Stretton , Robert (d. 1385)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26662. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Wharton, Henry (1691). Anglia Sacra, Pars Prima. Chiswell, London. Retrieved 16 January 2015.