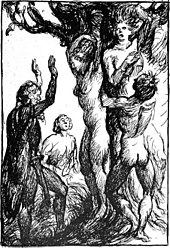

Ask and Embla

In Norse mythology, Ask and Embla (from Template:Lang-non)—male and female respectively—were the first two humans, created by the gods. The pair are attested in both the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, three gods, one of whom is Odin, find Ask and Embla and bestow upon them various corporeal and spiritual gifts. A number of theories have been proposed to explain the two figures, and there are occasional references to them in popular culture.

Etymology

Old Norse askr literally means "ash tree" but the etymology of embla is uncertain, and two possibilities of the meaning of embla are generally proposed. The first meaning, "elm tree", is problematic, and is reached by deriving *Elm-la from *Almilōn and subsequently to almr ("elm").[1] The second suggestion is "vine", which is reached through *Ambilō, which may be related to the Greek term ἄμπελος (ámpelos), itself meaning "vine, liana".[1] The latter etymology has resulted in a number of theories.

According to Benjamin Thorpe "Grimm says the word embla, emla, signifies a busy woman, from amr, ambr, aml, ambl, assiduous labour; the same relation as Meshia and Meshiane, the ancient Persian names of the first man and woman, who were also formed from trees."[2]

Attestations

In stanza 17 of the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá, the seeress reciting the poem states that Hœnir, Lóðurr and Odin once found Ask and Embla on land. The seeress says that the two were capable of very little, lacking in ørlög and says that they were given three gifts by the three gods:

- Old Norse:

- Ǫnd þau né átto, óð þau né hǫfðo,

- lá né læti né lito góða.

- Ǫnd gaf Óðinn, óð gaf Hœnir,

- lá gaf Lóðurr ok lito góða.[3]

- Benjamin Thorpe translation:

- Spirit they possessed not, sense they had not,

- blood nor motive powers, nor goodly colour.

- Spirit gave Odin, sense gave Hœnir,

- blood gave Lodur, and goodly colour.[4]

- Henry Adams Bellows translation:

- Soul they had not, sense they had not,

- Heat nor motion, nor goodly hue;

- Soul gave Othin, sense gave Hönir,

- Heat gave Lothur and goodly hue.[5]

The meaning of these gifts has been a matter of scholarly disagreement and translations therefore vary.[6]

According to chapter 9 of the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, the three brothers Vili, Vé, and Odin, are the creators of the first man and woman. The brothers were once walking along a beach and found two trees there. They took the wood and from it created the first human beings; Ask and Embla. One of the three gave them the breath of life, the second gave them movement and intelligence, and the third gave them shape, speech, hearing and sight. Further, the three gods gave them clothing and names. Ask and Embla go on to become the progenitors of all humanity and were given a home within the walls of Midgard.[7]

Theories

Indo-European origins

A Proto-Indo-European basis has been theorized for the duo based on the etymology of embla meaning "vine." In Indo-European societies, an analogy is derived from the drilling of fire and sexual intercourse. Vines were used as a flammable wood, where they were placed beneath a drill made of harder wood, resulting in fire. Further evidence of ritual making of fire in Scandinavia has been theorized from a depiction on a stone plate on a Bronze Age grave in Kivik, Scania, Sweden.[1]

Jaan Puhvel comments that "ancient myths teem with trite 'first couples' of the type of Adam and his by-product Eve. In Indo-European tradition, these range from the Vedic Yama and Yamī and the Iranian Mašya and Mašyānag to the Icelandic Askr and Embla, with trees or rocks as preferred raw material, and dragon's teeth or other bony substance occasionally thrown in for good measure".[8]

In his study of the comparative evidence for an origin of mankind from trees in Indo-European society, Anders Hultgård observes that "myths of the origin of mankind from trees or wood seem to be particularly connected with ancient Europe and Indo-Europe and Indo-European-speaking peoples of Asia Minor and Iran. By contrast the cultures of the Near East show almost exclusively the type of anthropogonic stories that derive man's origin from clay, earth or blood by means of a divine creation act".[9]

Other potential Germanic analogues

Two wooden figures—the Braak Bog Figures—of "more than human height" were unearthed from a peat bog at Braak in Schleswig, Germany. The figures depict a nude male and a nude female. Hilda Ellis Davidson comments that these figures may represent a "Lord and Lady" of the Vanir, a group of Norse gods, and that "another memory of [these wooden deities] may survive in the tradition of the creation of Ask and Embla, the man and woman who founded the human race, created by the gods from trees on the seashore".[10]

A figure named Æsc (Old English "ash tree") appears as the son of Hengest in the Anglo-Saxon genealogy for the kings of Kent. This has resulted in a number of theories that the figures may have had an earlier basis in pre-Norse Germanic mythology.[11]

Connections have been proposed between Ask and Embla and the Vandal kings Assi and Ambri, attested in Paul the Deacon's 7th century AD work Origo Gentis Langobardorum. There, the two ask the god Godan (Odin) for victory. The name Ambri, like Embla, likely derives from *Ambilō.[1]

Catalog of dwarfs

A stanza preceding the account of the creation of Ask and Embla in Völuspá provides a catalog of dwarfs, and stanza 10 has been considered as describing the creation of human forms from the earth. This may potentially mean that dwarfs formed humans, and that the three gods gave them life.[12] Carolyne Larrington theorizes that humans are metaphorically designated as trees in Old Norse works (examples include "trees of jewellery" for women and "trees of battle" for men) due to the origin of humankind stemming from trees; Ask and Embla.[13]

Modern depictions

Ask and Embla have been the subject of a number of references and artistic depictions.

A sculpture depicting the two, created by Stig Blomberg in 1948, stands in Sölvesborg in southern Sweden.

Ask and Embla are depicted on two of the sixteen wooden panels by Dagfin Werenskiold on Oslo City Hall.[14]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d Simek (2007:74).

- ^ Thorpe (1907:337).

- ^ Dronke (1997:11).

- ^ Thorpe (1866:5).

- ^ Bellows (1936:8).

- ^ Schach (1985:93).

- ^ Byock (2006:18).

- ^ Puhvel (1989 [1987]:284).

- ^ Hultgård (2006:62).

- ^ Davidson (1975:88—89).

- ^ Orchard (1997:8).

- ^ Lindow (2001:62—63).

- ^ Larrington (1999:279).

- ^ Municipality of Oslo (2001-06-26). "Yggdrasilfrisen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

References

- Bellows, Henry Adams (Trans.) (1936). The Poetic Edda. Princeton University Press. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2006). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1975). Scandinavian Mythology. Paul Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-03637-5

- Hultgård, Anders (2006). "The Askr and Embla Myth in a Comparative Perspective". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; Raudvere, Catharina (editors).Old Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X

- Dronke, Ursula (Trans.) (1997). The Poetic Edda: Volume II: Mythological Poems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-811181-9

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Puhvel, Jaan (1989 [1987]). Comparative Mythology. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3938-6

- Schach, Paul (1985). "Some Thoughts on Völuspá" as collected in Glendinning, R. J. Bessason, Heraldur (Editors). Edda: a Collection of Essays. University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 0-88755-616-7

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1907). The Elder Edda of Saemund Sigfusson. Norrœna Society.

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Frôða: The Edda of Sæmund the Learned. Part I. London: Trübner & Co.