Rectal prolapse

| Rectal prolapse | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Complete rectal prolapse, external rectal prolapse |

| |

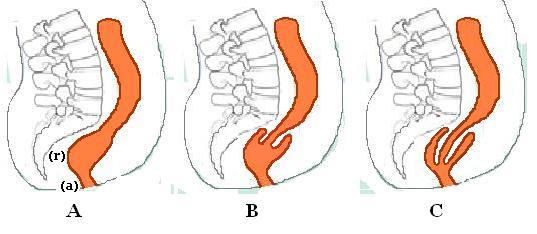

| A. full thickness external rectal prolapse, and B. mucosal prolapse. Note circumferential arrangement of folds in full thickness prolapse compared to radial folds in mucosal prolapse.[1] | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

Rectal prolapse is when the rectal walls have prolapsed to a degree where they protrude out the anus and are visible outside the body.[2] However, most researchers agree that there are 3 to 5 different types of rectal prolapse, depending on if the prolapsed section is visible externally, and if the full or only partial thickness of the rectal wall is involved.[3][4]

Rectal prolapse may occur without any symptoms, but depending upon the nature of the prolapse there may be mucous discharge (mucus coming from the anus), rectal bleeding, degrees of fecal incontinence and obstructed defecation symptoms.[5]

Rectal prolapse is generally more common in elderly women, although it may occur at any age and in either sex. It is very rarely life-threatening, but the symptoms can be debilitating if left untreated.[5] Most external prolapse cases can be treated successfully, often with a surgical procedure. Internal prolapses are traditionally harder to treat and surgery may not be suitable for many patients.

Classification

The different kinds of rectal prolapse can be difficult to grasp, as different definitions are used and some recognize some subtypes and others do not. Essentially, rectal prolapses may be

- full thickness (complete), where all the layers of the rectal wall prolapse, or involve the mucosal layer only (partial)

- external if they protrude from the anus and are visible externally, or internal if they do not

- circumferential, where the whole circumference of the rectal wall prolapse, or segmental if only parts of the circumference of the rectal wall prolapse

- present at rest, or occurring during straining.

External (complete) rectal prolapse (rectal procidentia, full thickness rectal prolapse, external rectal prolapse) is a full thickness, circumferential, true intussusception of the rectal wall which protrudes from the anus and is visible externally.[6][7]

Internal rectal intussusception (occult rectal prolapse, internal procidentia) can be defined as a funnel shaped infolding of the upper rectal (or lower sigmoid) wall that can occur during defecation.[8] This infolding is perhaps best visualised as folding a sock inside out,[9] creating "a tube within a tube".[10] Another definition is "where the rectum collapses but does not exit the anus".[11] Many sources differentiate between internal rectal intussusception and mucosal prolapse, implying that the former is a full thickness prolapse of rectal wall. However, a publication by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons stated that internal rectal intussusception involved the mucosal and submucosal layers separating from the underlying muscularis mucosa layer attachments, resulting in the separated portion of rectal lining "sliding" down.[5] This may signify that authors use the terms internal rectal prolapse and internal mucosal prolapse to describe the same phenomena.

Mucosal prolapse (partial rectal mucosal prolapse)[12] refers to prolapse of the loosening of the submucosal attachments to the muscularis propria of the distal rectummucosal layer of the rectal wall. Most sources define mucosal prolapse as an external, segmental prolapse which is easily confused with prolapsed (3rd or 4th degree) hemorrhoids (piles).[9] However, both internal mucosal prolapse (see below) and circumferential mucosal prolapse are described by some.[12] Others do not consider mucosal prolapse a true form of rectal prolapse.[13]

Internal mucosal prolapse (rectal internal mucosal prolapse, RIMP) refers to prolapse of the mucosal layer of the rectal wall which does not protrude externally. There is some controversy surrounding this condition as to its relationship with hemorrhoidal disease, or whether it is a separate entity.[14] The term "mucosal hemorrhoidal prolapse" is also used.[15]

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS, solitary rectal ulcer, SRU) occurs with internal rectal intussusception and is part of the spectrum of rectal prolapse conditions.[5] It describes ulceration of the rectal lining caused by repeated frictional damage as the internal intussusception is forced into the anal canal during straining. SRUS can be considered a consequence of internal intussusception, which can be demonstrated in 94% of cases.

Mucosal prolapse syndrome (MPS) is recognized by some. It includes solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, rectal prolapse, proctitis cystica profunda, and inflammatory polyps.[16][17] It is classified as a chronic benign inflammatory disorder.

Rectal prolapse and internal rectal intussusception has been classified according to the size of the prolapsed section of rectum, a function of rectal mobility from the sacrum and infolding of the rectum. This classification also takes into account sphincter relaxation:[18]

- Grade I: nonrelaxation of the sphincter mechanism (anismus)

- Grade II: mild intussusception

- Grade III: moderate intussusception

- Grade IV: severe intussusception

- Grade V: rectal prolapse

Rectal internal mucosal prolapse has been graded according to the level of descent of the intussusceptum, which was predictive of symptom severity:[19]

- first degree prolapse is detectable below the anorectal ring on straining

- second degree when it reached the dentate line

- third degree when it reached the anal verge

B. Recto-rectal intussusception

C. Recto-anal intussusception

The most widely used classification of internal rectal prolapse is according to the height on the rectal/sigmoid wall from which they originate and by whether the intussusceptum remains within the rectum or extends into the anal canal. The height of intussusception from the anal canal is usually estimated by defecography.[10]

Recto-rectal (high) intussusception (intra-rectal intussusception) is where the intussusception starts in the rectum, does not protrude into the anal canal, but stays within the rectum. (i.e. the intussusceptum originates in the rectum and does not extend into the anal canal. The intussuscipiens includes rectal lumen distal to the intussusceptum only). These are usually intussusceptions that originate in the upper rectum or lower sigmoid.[10]

Recto-anal (low) intussusception (intra-anal intussusception) is where the intussusception starts in the rectum and protrudes into the anal canal (i.e. the intussusceptum originates in the rectum, and the intussuscipiens includes part of the anal canal)

An Anatomico-Functional Classification of internal rectal intussusception has been described,[10] with the argument that other factors apart from the height of intussusception above the anal canal appear to be important to predict symptomology. The parameters of this classification are anatomic descent, diameter of intussuscepted bowel, associated rectal hyposensitivity and associated delayed colonic transit:

- Type 1: Internal recto-rectal intussusception

- Type 1W Wide lumen

- Type 1N Narrowed lumen

- Type 2: Internal recto-anal intussusception

- Type 2W Wide Lumen

- Type 2N Narrowed lumen

- Type 2M Narrowed internal lumen with associated rectal hyposensitivity or early megarectum

- Type 3: Internal-external recto-anal intussusception

Diagnosis

History

Patients may have associated gynecological conditions which may require multidisciplinary management.[5] History of constipation is important because some of the operations may worsen constipation. Fecal incontinence may also influence the choice of management.

Physical examination

Rectal prolapse may be confused easily with prolapsing hemorrhoids.[5] Mucosal prolapse also differs from prolapsing (3rd or 4th degree) hemorrhoids, where there is a segmental prolapse of the hemorrhoidal tissues at the 3,7 and 11’O clock positions.[12] Mucosal prolapse can be differentiated from a full thickness external rectal prolapse (a complete rectal prolapse) by the orientation of the folds (furrows) in the prolapsed section. In full thickness rectal prolapse, these folds run circumferential. In mucosal prolapse, these folds are radially.[9] The folds in mucosal prolapse are usually associated with internal hemorrhoids. Furthermore, in rectal prolapse, there is a sulcus present between the prolapsed bowel and the anal verge, whereas in hemorrhoidal disease there is no sulcus.[3] Prolapsed, incarcerated hemorrhoids are extremely painful, whereas as long as a rectal prolapse is not strangulated, it gives little pain and is easy to reduce.[5]

The prolapse may be obvious, or it may require straining and squatting to produce it.[5] The anus is usually patulous, (loose, open) and has reduced resting and squeeze pressures.[5] Sometimes it is necessary to observe the patient while they strain on a toilet to see the prolapse happen[20] (the perineum can be seen with a mirror or by placing an endoscope in the bowl of the toilet).[9] A phosphate enema may need to be used to induce straining.[3]

The perianal skin may be macerated (softening and whitening of skin that is kept constantly wet) and show excoriation.[9]

Proctoscopy/sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy

These may reveal congestion and edema (swelling) of the distal rectal mucosa,[20] and in 10-15% of cases there may be a solitary rectal ulcer on the anterior rectal wall.[5] Localized inflammation or ulceration can be biopsied, and may lead to a diagnosis of SRUS or colitis cystica profunda.[5] Rarely, a neoplasm (tumour) may form on the leading edge of the intussusceptum. In addition, patients are frequently elderly and therefore have increased incidence of colorectal cancer. Full length colonoscopy is usually carried out in adults prior to any surgical intervention.[5] These investigations may be used with contrast media (barium enema) which may show the associated mucosal abnormalities.[9]

Videodefecography

This investigation is used to diagnose internal intussusception, or demonstrate a suspected external prolapse that could not be produced during the examination.[3] It is usually not necessary with obvious external rectal prolapse.[9] Defecography may demonstrate associated conditions like cystocele, vaginal vault prolapse or enterocele.[5]

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit studies may be used to rule out colonic inertia if there is a history of severe constipation.[3][5] Continent prolapse patients with slow transit constipation, and who are fit for surgery may benefit from subtotal colectomy with rectopexy.[5]

Anorectal manometry

This investigation objectively documents the functional status of the sphincters. However, the clinical significance of the findings are disputed by some.[9] It may be used to assess for pelvic floor dyssenergia,[5] (anismus is a contraindication for certain surgeries, e.g. STARR), and these patients may benefit from post-operative biofeedback therapy. Decreased squeeze and resting pressures are usually the findings, and this may predate the development of the prolapse.[5] Resting tone is usually preserved in patients with mucosal prolapse.[20] In patients with reduced resting pressure, levatorplasty may be combined with prolapse repair to further improve continence.[9]

Anal electromyography/Pudendal nerve testing

May be used to evaluate incontinence, but there is disagreement about what relevance the results may show, as rarely do they mandate a change of surgical plan.[5] There may be denervation of striated musculature on the electromyogram.[20] Increased nerve conduction periods (nerve damage), this may be significant in predicting post-operative incontinence.[5]

Complete rectal prolapse

Rectal prolapse is a "falling down" of the rectum so that it is visible externally. The appearance is of a reddened, proboscis-like object through the anal sphincters. Patients find the condition embarrassing.[9] The symptoms can be socially debilitating without treatment,[5] but it is rarely life-threatening.[9]

The true incidence of rectal prolapse is unknown, but it is thought to be uncommon. As most sufferers are elderly, the condition is generally under-reported.[21] It may occur at any age, even in children,[22] but there is peak onset in the fourth and seventh decades.[3] Women over 50 are six times more likely to develop rectal prolapse than men. It is rare in men over 45 and in women under 20.[20] When males are affected, they tend to be young and report significant bowel function symptoms, especially obstructed defecation,[5] or have a predisposing disorder (e.g., congenital anal atresia).[9] When children are affected, they are usually under the age of 3.

35% of women with rectal prolapse have never had children,[5] suggesting that pregnancy and labour are not significant factors. Anatomical differences such as the wider pelvic outlet in females may explain the skewed gender distribution.[9]

Associated conditions, especially in younger patients include autism, developmental delay syndromes and psychiatric conditions requiring several medications.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms include:

- history of a protruding mass.[3]

- degrees of fecal incontinence, (50-80% of patients)[3][5] which may simply present as a mucous discharge.[3]

- constipation[5] (20-50% of patients)[5] also described as tenesmus (a sensation of incomplete evacuation of stool) and obstructed defecation.[3]

- a feeling of bearing down.[20]

- rectal bleeding[3]

- diarrhea[20] and erratic bowel habits.

Initially, the mass may protrude through the anal canal only during defecation and straining, and spontaneously return afterwards. Later, the mass may have to be pushed back in following defecation. This may progress to a chronically prolapsed and severe condition, defined as spontaneous prolapse that is difficult to keep inside, and occurs with walking, prolonged standing,[5] coughing or sneezing (Valsalva maneuvers).[3] A chronically prolapsed rectal tissue may undergo pathological changes such as thickening, ulceration and bleeding.[5]

If the prolapse becomes trapped externally outside the anal sphincters, it may become strangulated and there is a risk of perforation.[20] This may require an urgent surgical operation if the prolapse cannot be manually reduced.[5] Applying granulated sugar on the exposed rectal tissue can reduce the edema (swelling) and facilitate this.[20]

Cause

The precise cause is unknown,[3][9][8] and has been much debated.[5] In 1912 Moschcowitz proposed that rectal prolapse was a sliding hernia through a pelvic fascial defect.[9]

This theory was based on the observation that rectal prolapse patients have a mobile and unsupported pelvic floor, and a hernia sac of peritoneum from the Pouch of Douglas and rectal wall can be seen.[5] Other adjacent structures can sometimes be seen in addition to the rectal prolapse.[5] Although a pouch of Douglas hernia, originating in the cul de sac of Douglas, may protrude from the anus (via the anterior rectal wall),[20] this is a different situation from rectal prolapse.

Shortly after the invention of defecography, In 1968 Broden and Snellman used cinedefecography to show that rectal prolapse begins as a circumferential intussusception of the rectum,[3][9] which slowly increases over time.[20] The leading edge of the intussusceptum may be located at 6–8 cm or at 15–18 cm from the anal verge.[20] This proved an older theory from the 18th century by John Hunter and Albrecht von Haller that this condition is essentially a full-thickness rectal intussusception, beginning about 3 inches above the dentate line and protruding externally.[5]

Since most patients with rectal prolapse have a long history of constipation,[9] it is thought that prolonged, excessive and repetitive straining during defecation may predispose to rectal prolapse.[3][8][20][23][24][25] Since rectal prolapse itself causes functional obstruction, more straining may result from a small prolapse, with increasing damage to the anatomy.[8] This excessive straining may be due to predisposing pelvic floor dysfunction (e.g. obstructed defecation) and anatomical factors:[9][20]

- Abnormally low descent of the peritoneum covering the anterior rectal wall

- poor posterior rectal fixation, resulting in loss of posterior fixation of the rectum to the sacral curve[5]

- loss of the normal horizontal position of the rectum[3] with lengthening (redundant rectosigmoid)[3][5] and downward displacement of the sigmoid and rectum

- long rectal mesentery[3]

- a deep cul-de-sac[3][5]

- levator diastasis[3][5]

- a patulous, weak anal sphincter[3][5]

Some authors question whether these abnormalities are the cause, or secondary to the prolapse.[3] Other predisposing factors/associated conditions include:

- pregnancy[3] (although 35% of women who develop rectal prolapse are nulliparous)[3] (have never given birth)

- previous surgery[3] (30-50% of females with the condition underwent previous gynecological surgery)[3]

- pelvic neuropathies and neurological disease[20]

- high gastrointestinal helminth loads (e.g. Whipworm)[26]

- COPD[citation needed]

- cystic fibrosis[citation needed]

The association with uterine prolapse (10-25%) and cystocele (35%) may suggest that there is some underlying abnormality of the pelvic floor that affects multiple pelvic organs.[3] Proximal bilateral pudendal neuropathy has been demonstrated in patients with rectal prolapse who have fecal incontinence.[5] This finding was shown to be absent in healthy subjects, and may be the cause of denervation-related atrophy of the external anal sphincter. Some authors suggest that pudendal nerve damage is the cause for pelvic floor and anal sphincter weakening, and may be the underlying cause of a spectrum of pelvic floor disorders.[5]

Sphincter function in rectal prolapse is almost always reduced.[3] This may be the result of direct sphincter injury by chronic stretching of the prolapsing rectum. Alternatively, the intussuscepting rectum may lead to chronic stimulation of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR - contraction of the external anal sphincter in response to stool in the rectum). The RAIR was shown to be absent or blunted. Squeeze (maximum voluntary contraction) pressures may be affected as well as the resting tone. This is most likely a denervation injury to the external anal sphincter.[3]

The assumed mechanism of fecal incontinence in rectal prolapse is by the chronic stretch and trauma to the anal sphincters and the presence of a direct conduit (the intussusceptum) connecting rectum to the external environment which is not guarded by the sphincters.[5]

The assumed mechanism of obstructed defecation is by disruption to the rectum and anal canal's ability to contract and fully evacuate rectal contents. The intussusceptum itself may mechanically obstruct the rectoanal lumen, creating a blockage that straining, anismus and colonic dysmotility exacerbate.[5]

Some believe that internal rectal intussusception represents the initial form of a progressive spectrum of disorders the extreme of which is external rectal prolapse. The intermediary stages would be gradually increasing sizes of intussusception. However, internal intussusception rarely progresses to external rectal prolapse.[27] The factors that result in a patient progressing from internal intussusception to a full thickness rectal prolapse remain unknown.[5] Defecography studies demonstrated that degrees of internal intussusception are present in 40% of asymptomatic subjects, raising the possibility that it represents a normal variant in some, and may predispose patients to develop symptoms, or exacerbate other problems.[28]

Treatment

Conservative

Surgery is thought to be the only option to potentially cure a complete rectal prolapse.[6] For people with medical problems that make them unfit for surgery, and those who have minimal symptoms, conservative measures may be beneficial. Dietary adjustments, including increasing dietary fiber may be beneficial to reduce constipation, and thereby reduce straining.[6] A bulk forming agent (e.g. psyllium) or stool softener can also reduce constipation.[6]

Surgical

Surgery is often required to prevent further damage to the anal sphincters. The goals of surgery are to restore the normal anatomy and to minimize symptoms. There is no globally agreed consensus as to which procedures are more effective,[6] and there have been over 50 different operations described.[5]

Surgical approaches in rectal prolapse can be either perineal or abdominal. A perineal approach (or trans-perineal) refers to surgical access to the rectum and sigmoid colon via incision around the anus and perineum (the area between the genitals and the anus).[29] Abdominal approach (trans-abdominal approach) involves the surgeon cutting into the abdomen and gaining surgical access to the pelvic cavity. Procedures for rectal prolapse may involve fixation of the bowel (rectopexy), or resection (a portion removed), or both.[6] Trans-anal (endo-anal) procedures are also described where access to the internal rectum is gained through the anus itself.

Abdominal procedures

The abdominal approach carries a small risk of impotence in males (e.g. 1-2% in abdominal rectopexy).[9] Abdominal operations may be open or laparoscopic (keyhole surgery).[3]

Laparoscopic procedures Recovery time following laparoscopic surgery is shorter and less painful than following traditional abdominal surgery.[29] Instead of opening the pelvic cavity with a wide incision (laparotomy), a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) and surgical instruments are inserted into the pelvic cavity via small incisions.[29] Rectopexy and anterior resection have been performed laparoscopically with good results.

Perineal procedures

The perineal approach generally results in less post-operative pain and complications, and a reduced length of hospital stay. These procedures generally carry a higher recurrence rate and poorer functional outcome.[5] The perineal procedures include perineal rectosigmoidectomy and Delorme repair.[3] Elderly, or other medically high-risk patients are usually treated by perineal procedures,[3] as they can be performed under a regional anesthetic, or even local anesthetic with intravenous sedation, thus avoid the risks of a general anesthetic.[9] Alternatively, perineal procedures may be selected to reduce risk of nerve damage, for example in young male patients for whom sexual dysfunction may be a major concern.[5]

Perineal rectosigmoidectomy

The goal of Perineal rectosigmoidectomy is to resect, or remove, the redundant bowel. This is done through the perineum. The lower rectum is anchored to the sacrum through fibrosis in order to prevent future prolapse.[6] The full thickness of the rectal wall is incised at a level just above the dentate line. Redundant rectal and sigmoid wall is removed and the new edge of colon is reconnected (anastomosed) with the anal canal with stitches or staples.[9] This procedure may be combined with levatorplasty, to tighten the pelvic muscles.[6] A combined a perineal proctosigmoidectomy with anterior levatoroplasty is also called an Altemeier procedure.[3] Levatorplasty is performed to correct elvator diastasis which is commonly associated with rectal prolapse.[3] Perineal rectosigmoidectomy was first introduced by Mikulicz in 1899, and it remained the preferred treatment in Europe for many years.[3] It was Popularized by Altemeier.[9] The procedure is simple, safe and effective.[3] Continence Levatorplasty may enhance restoration of continence (2/3 of patients).[3] Complications occur in less than 10% of cases, and include pelvic bleeding, pelvic abscess and anastomotic dehiscence (splitting apart of the stitches inside), bleeding or leak at a dehiscence[3] Mortality is low.[9] Recurrence rates are higher than for abdominal repair,[3] 16-30%, but more recent studies give lower recurrence rates.[3] Additional levatoroplasty can reduce recurrence rates to 7%.[3]

Delorme Procedure

This is a modification of the perineal rectosigmoidectomy, differing in that only the mucosa and submucosa are excised from the prolapsed segment, rather than full thickness resection.[9] The prolapse is exposed if it is not already present, and the mucosal and submucosal layers are stripped from the redundant length of bowel. The muscle layer that is left is plicated (folded) and placed as a buttress above the pelvic floor.[6] The edges of the mucosal are then stitched back together. "Mucosal proctectomy" was first discussed by Delorme in 1900,[9] now it is becoming more popular again as it has low morbidity and avoids an abdominal incision, while effectively repairing the prolapse.[3] The procedure is ideally suited to those patients with full-thickness prolapse limited to partial circumference (e.g., anterior wall) or less-extensive prolapse (perineal rectosigmoidectomy may be difficult in this situation).[3][9] Fecal incontinence is improved following surgery (40%–75% of patients).[5][9] Post operatively, both mean resting and squeeze pressures were increased.[5] Constipation is improved in 50% of cases,[5] but often urgency and tenesmus are created. Complications, including infection, urinary retention, bleeding, anastomotic dehiscence (opening of the stitched edges inside), stricture (narrowing of the gut lumen), diarrhea, and fecal impaction occur in 6-32% of cases.[5][9] Mortality occurs in 0–2.5% cases.[9] There is a higher recurrence rate than abdominal approaches (7-26% cases).[5][9]

Anal encirclement (Thirsch procedure)

This procedure can be carried out under local anaesthetic. After reduction of the prolapse, a subcutaneous suture (a stich under the skin) or other material is placed encircling the anus, which is then made taut to prevent further prolapse.[6] Placing silver wire around the anus first described by Thiersch in 1891.[9] Materials used include nylon, silk, silastic rods, silicone, Marlex mesh, Mersilene mesh, fascia, tendon, and Dacron.[9] This operation does not correct the prolapse itself, it merely supplements the anal sphincter, narrowing the anal canal with the aim of preventing the prolapse from becoming external, meaning it remains in the rectum.[9] This goal is achieved in 54-100% cases. Complications include breakage of the encirclement material, fecal impaction, sepsis, and erosion into the skin or anal canal. Recurrence rates are higher that the other perineal procedures. This procedure is most often used for people who have a severe condition or who have a high risk of adverse effects from general anesthetic,[6] and who may not tolerate other perineal procedures.

Internal rectal intussusception

Internal rectal intussusception (rectal intussusception, internal intussusception, internal rectal prolapse, occult rectal prolapse, internal rectal procidentia and rectal invagination) is a medical condition defined as a funnel shaped infolding of the rectal wall that can occur during defecation.[8]

This phenomenon was first described in the late 1960s when defecography was first developed and became widespread.[5] Degrees of internal intussusception have been demonstrated in 40% of asymptomatic subjects, raising the possibility that it represents a normal variant in some, and may predispose patients to develop symptoms, or exacerbate other problems.[28]

Symptoms

Internal intussusception may be asymptomatic, but common symptoms include:[3]

- Fecal leakage[30]

- Sensation of obstructed defecation (tenesmus).[31]

- Pelvic pain.[3]

- Rectal bleeding.[3]

Recto-rectal intussusceptions may be asymptomatic, apart from mild obstructed defecation. "interrupted defaecation" in the morning is thought by some to be characteristic.[10]

Recto-anal intussusceptions commonly give more severe symptoms of straining, incomplete evacuation, need for digital evacuation of stool, need for support of the perineum during defecation, urgency, frequency or intermittent fecal incontinence.[10]

It has been observed that intussusceptions of thickness ≥3 mm, and those that appear to cause obstruction to rectal evacuation may give clinical symptoms.[32][33]

Cause

There are two schools of thought regarding the nature of internal intussusception, viz: whether it is a primary phenomenon, or secondary to (a consequence of) another condition.

Some believe that it represents the initial form of a progressive spectrum of disorders the extreme of which is external rectal prolapse. The intermediary stages would be gradually increasing sizes of intussusception. The folding section of rectum can cause repeated trauma to the mucosa, and can cause solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.[9] However, internal intussusception rarely progresses to external rectal prolapse.[27]

Others argue that the majority of patients appear to have rectal intussusception as a consequence of obstructed defecation rather than a cause,[34][35] possibly related to excessive straining in patients with obstructed defecation.[32] Patients with other causes of obstructed defecation (outlet obstruction) like anismus also tend to have higher incidence of internal intussusception. Enteroceles are coexistent in 11% of patients with internal intussusception.[36] Symptoms of internal intussusception overlap with those of rectocele, indeed the 2 conditions can occur together.[37]

Patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome combined with internal intussusception (as 94% of SRUS patients have) were shown to have altered rectal wall biomechanics compared to patients with internal intussusception alone.[38] The presumed mechanism of the obstructed defecation is by telescoping of the intussusceptum, occluding the rectal lumen during attempted defecation.[32] One study analysed resected rectal wall specimens in patients with obstructed defecation associated with rectal intussusception undergoing stapled trans-anal rectal resection. They reported abnormalities of the enteric nervous system and estrogen receptors.[39] One study concluded that intussusception of the anterior rectal wall shares the same cause as rectocele, namely deficient recto-vaginal ligamentous support.[40]

Comorbidities and complications

The following conditions occur more commonly in patients with internal rectal intussusception than in the general population:

Diagnosis

Unlike external rectal prolapse, internal rectal intussusception is not visible externally, but it may still be diagnosed by digital rectal examination, while the patient strains as if to defecate.[10] Imaging such as a defecating proctogram[43] or dynamic MRI defecography can demonstrate the abnormal folding of the rectal wall. Some have advocated the use of anorectal physiology testing (anorectal manometry).[5]

Treatment

Non surgical measures to treat internal intussusception include pelvic floor retraining,[44] a bulking agent (e.g. psyllium), suppositories or enemas to relieve constipation and straining.[20] If there is incontinence (fecal leakage or more severe FI), or paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor (anismus), then biofeedback retraining is indicated.[45] Some researchers advise that internal intussusception be managed conservatively, compared to external rectal prolapse which usually requires surgery.[46]

As with external rectal prolapse, there are a great many different surgical interventions described. Generally, a section of rectal wall can be resected (removed), or the rectum can be fixed (rectopexy) to its original position against the sacral vertebrae, or a combination of both methods. Surgery for internal rectal prolapse can be via the abdominal approach or the transanal approach.[47]

It is clear that there is a wide spectrum of symptom severity, meaning that some patients may benefit from surgery and others may not. Many procedures receive conflicting reports of success, leading to a lack of any consensus about the best way to manage this problem.[45] Relapse of the intussusception after treatment is a problem. Two of the most commonly employed procedures are discussed below.

laparoscopic ventral (mesh) rectopexy (LVR)

This procedure aims to "[correct] the descent of the posterior and middle pelvic compartments combined with reinforcement of the rectovaginal septum".[47]

Rectopexy has been shown to improve anal incontinence (fecal leakage) in patients with rectal intussusception.[48] The operation has been shown to have low recurrence rate (around 5%).[49] It also improves obstructed defecation symptoms.[50]

Complications include constipation, which is reduced if the technique does not use posterior rectal mobilization (freeing the rectum from its attached back surface).[51]

The advantage of the laproscopic approach is decreased healing time and less complications.[49]

Stapled trans-anal rectal resection (STARR)

This operation aims to "remove the anorectal mucosa circumferential and reinforce the anterior anorectal junction wall with the use of a circular stapler".[41][42] In contrast to other methods, STARR does not correct the descent of the rectum, it removes the redundant tissue.[47] The technique was developed from a similar stapling procedure for prolapsing hemorrhoids. Since, specialized circular staplers have been developed for use in external rectal prolapse and internal rectal intussusception.[52]

Complications, sometimes serious, have been reported following STARR,[53][54][55][56][57] but the procedure is now considered safe and effective.[56] STARR is contraindicated in patients with weak sphincters (fecal incontinence and urgency are a possible complication) and with anismus (paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor during attempted defecation).[56] The operation has been shown to improve rectal sensitivity and decrease rectal volume, the reason thought to create urgency.[47] 90% of patients do not report urgency 12 months after the operation. The anal sphincter may also be stretched during the operation. STARR was compared with biofeedback and found to be more effective at reducing symptoms and improving quality of life.[58]

Mucosal prolapse

Rectal mucosal prolapse (mucosal prolapse, anal mucosal prolapse) is a sub-type of rectal prolapse, and refers to abnormal descent of the rectal mucosa through the anus.[20] It is different to an internal intussusception (occult prolapse) or a complete rectal prolapse (external prolapse, procidentia) because these conditions involve the full thickness of the rectal wall, rather than only the mucosa (lining).[12]

Mucosal prolapse is a different condition to prolapsing (3rd or 4th degree) hemorrhoids,[12] although they may look similar.

Rectal mucosal prolapse can be a cause of obstructed defecation (outlet obstruction).[8] and rectal malodor.

Symptoms

Symptom severity increases with the size of the prolapse, and whether it spontaneously reduces after defecation, requires manual reduction by the patient, or becomes irreducible. The symptoms are identical to advanced hemorrhoidal disease,[12] and include:

- Fecal leakage causing staining of undergarments

- Rectal bleeding

- Mucous rectal discharge

- Rectal pain

- Pruritus ani

Cause

The condition, along with complete rectal prolapse and internal rectal intussusception, is thought to be related to chronic straining during defecation and constipation.

Mucosal prolapse occurs when the results from loosening of the submucosal attachments (between the mucosal layer and the muscularis propria) of the distal rectum.[3] The section of prolapsed rectal mucosa can become ulcerated, leading to bleeding.

Diagnosis

Mucosal prolapse can be differentiated from a full thickness external rectal prolapse (a complete rectal prolapse) by the orientation of the folds (furrows) in the prolapsed section. In full thickness rectal prolapse, these folds run circumferential. In mucosal prolapse, these folds are radially.[9] The folds in mucosal prolapse are usually associated with internal hemorrhoids.[20]

Treatment

EUA (examination under anesthesia) of anorectum and banding of the mucosa with rubber bands.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and colitis cystica profunda

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS, SRU), is a disorder of the rectum and anal canal, caused by straining and increased pressure during defecation. This increased pressure causes the anterior portion of the rectal lining to be forced into the anal canal (an internal rectal intussusception). The lining of the rectum is repeatedly damaged by this friction, resulting in ulceration. SRUS can therefore considered to be a consequence of internal intussusception (a sub type of rectal prolapse), which can be demonstrated in 94% of cases. It may be asymptomatic, but it can cause rectal pain, rectal bleeding, rectal malodor, incomplete evacuation and obstructed defecation (rectal outlet obstruction).

Symptoms

- Straining during defecation

- Mucous rectal discharge

- Rectal bleeding

- Sensation of incomplete evacuation (tenesmus)

- constipation, or more rarely diarrhea

- fecal incontinence (rarely)

Prevalence

The condition is thought to be uncommon. It usually occurs in young adults, but children can be affected too.[60]

Cause

The essential cause of SRUS is thought to be related to too much straining during defecation.

Overactivity of the anal sphincter during defecation causes the patient to require more effort to expel stool. This pressure is produced by the modified valsalva manovoure (attempted forced exhalation against a closed glottis, resulting in increased abdominal and intra-rectal pressure). Patiest with SRUS were shown to have higher intra-rectal pressures when straining than healthy controls.[61] SRUS is also associated with prolonged and incomplete evacuation of stool.[62]

More effort is required because of concomitant anismus, or non-relaxation/paradoxical contraction of puborectalis (which should normally relax during defecation).[63] The increased pressure forces the anterior rectal lining against the contracted puborectalis and frequently the lining prolapses into the anal canal during straining and then returns to its normal position afterwards.

The repeated trapping of the lining can cause the tissue to become swollen and congested. Ulceration is thought to be caused by resulting poor blood supply (ischemia), combined with repeated frictional trauma from the prolapsing lining, and exposure to increased pressure are thought to cause ulceration. Trauma from hard stools may also contribute.

The site of the ulcer is typically on the anterior wall of the rectal ampulla, about 7–10 cm from the anus. However, the area may of ulceration may be closer to the anus, deeper inside, or on the lateral or posterior rectal walls. The name "solitary" can be misleading since there may be more than one ulcer present. Furthermore, there is a "preulcerative phase" where there is no ulcer at all.[64]

Pathological specimens of sections of rectal wall taken from SRUS patients show thickening and replacement of muscle with fibrous tissue and excess collagen.[65] Rarely, SRUS can present as polyps in the rectum.[66][67]

SRUS is therefore associated and with internal, and more rarely, external rectal prolapse.[62] Some believe that SRUS represents a spectrum of different diseases with different causes.[68]

Another condition associated with internal intussusception is colitis cystica profunda (also known as CCP, or proctitis cystica profunda), which is cystica profunda in the rectum. Cystica profunda is characterized by formation of mucin cysts in the muscle layers of the gut lining, and it can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract. When it occurs in the rectum, some believe to be an interchangeable diagnosis with SRUS since the histologic features of the conditions overlap.[69][70] Indeed, CCP is managed identically to SRUS.[71]

Electromyography may show pudendal nerve motor latency.[17]

Complications

Complications are uncommon, but include massive rectal bleeding, ulceration into the prostate gland or formation of a stricture.[72][73][74] Very rarely, cancer can arise on the section of prolapsed rectal lining.[16]

Diagnosis and investigations

SRUS is commonly misdiagnosed, and the diagnosis is not made for 5–7 years.[60] Clinicians may not be familiar with the condition, and treat for Inflammatory bowel disease, or simple constipation.[75][76]

The thickened lining or ulceration can also be mistaken for types of cancer.[77][78][79][80]

The differential diagnosis of SRUS (and CCP) includes:[9]

- polyps

- endometriosis

- inflammatory granulomas

- infectious disorders

- drug-induced colitis

- mucus-producing adenocarcinoma

Defecography, sigmoidoscopy, transrectal ultrasound, mucosal biopsy, anorectal manometry and electromyography have all been used to diagnose and study SRUS.[17][63] Some recommend biopsy as essential for diagnosis since ulcerations may not always be present, and others state defecography as the investigation of choice to diagnose SRUS.[59][70][75]

Treatment

Although SRUS is not a medically serious disease, it can be the cause of significantly reduced quality of life for patients. It is difficult to treat, and treatment is aimed at minimizing symptoms.

Stopping straining during bowel movements, by use of correct posture, dietary fiber intake (possibly included bulk forming laxatives such as psyllium), stool softeners (e.g. polyethylene glycol,[81][82] and biofeedback retraining to coordinate pelvic floor during defecation.[83][84]

Surgery may be considered, but only if non surgical treatment has failed and the symptoms are severe enough to warrant the intervention. Improvement with surgery is about 55-60%.[85]

Ulceration may persist even when symptoms resolve.[86]

Mucosal prolapse syndrome

A group of conditions known as Mucosal prolapse syndrome (MPS) has now been recognized. It includes SRUS, rectal prolapse, proctitis cystica profunda, and inflammatory polyps.[16][17] It is classified as a chronic benign inflammatory disorder. The unifying feature is varying degrees of rectal prolapse, whether internal intussusception (occult prolapse) or external prolapse.

Pornography

Rosebud pornography (or rosebudding or rectal prolapse pornography) is an anal sex practice which occurs in some extreme anal pornography wherein a pornographic actor or actress performs a rectal prolapse wherein the walls of the rectum slip out of the anus. A rectal prolapse is a serious medical condition that requires the attention of a medical professional. However, in rosebud pornography it is performed deliberately. Michelle Lhooq, writing for VICE, argues that rosebudding is an example of producers making 'extreme' content due to the easy availability of free pornography on the internet. She also argues that rosebudding is a way for pornographic actors and actresses to distinguish themselves.[87] Repeated rectal prolapses can cause bowel problems and anal leakage and therefore risk the health of pornographic actors or actresses who participate in them.[87] Lhooq also argues that some who participate in this form of pornography are unaware of the consequences.[87]

Terminology

Prolapse refers to "the falling down or slipping of a body part from its usual position or relations". It is derived from the Latin pro- - "forward" + labi - "to slide". "Prolapse". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Prolapse can refer to many different medical conditions other than rectal prolapse.

procidentia has a similar meaning to prolapse, referring to "a sinking or prolapse of an organ or part". It is derived from the Latin procidere - "to fall forward".[88] Procidentia usually refers to uterine prolapse, but rectal procidentia can also be a synonym for rectal prolapse.

Intussusception is defined as invagination (infolding), especially referring to "the slipping of a length of intestine into an adjacent portion". It is derived from the Latin intus - "within" and susceptio - "action of undertaking", from suscipere - "to take up". "Intussusception". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Rectal intussusception is not to be confused with other intussusceptions involving colon or small intestine, which can sometimes be a medical emergency. Rectal intussusception by contrast is not life-threatening.

Intussusceptum refers to the proximal section of rectal wall, which telescopes into the lumen of the distal section of rectum (termed the intussuscipiens).[9] What results is 3 layers of rectal wall overlaid. From the lumen outwards, the first layer is the proximal wall of the intussusceptum, the middle is the wall of the intussusceptum folded back on itself, and the outer is the distal rectal wall, the intussuscipiens.[9]

See also

References

- ^ Hammond, K; Beck, DE; Margolin, DA; Whitlow, CB; Timmcke, AE; Hicks, TC (Spring 2007). "Rectal prolapse: a 10-year experience". The Ochsner Journal. 7 (1): 24–32. PMC 3096348. PMID 21603476.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Altomare, Donato F.; Pucciani, Filippo (2007). Rectal Prolapse: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Springer. p. 12. ISBN 978-88-470-0683-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au Kim, Donald G. "ASCRS core subjects: Prolapse andIntussusception". ASCRS. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Kiran, Ravi Pokala. "How stapled resection can treat rectal prolapse". Contemporary surgery online. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba Madhulika, G; Varma, MD. "Prolapse, Intussusception, & SRUS". ASCRS. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tou, Samson; Brown, Steven R.; Nelson, Richard L. (2015-11-24). "Surgery for complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD001758. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001758.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7073406. PMID 26599079.

- ^ Altomare, Pucciani (2007) p.14

- ^ a b c d e f Wexner, edited by Andrew P. Zbar, Steven D. (2010). Coloproctology. New York: Springer. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-84882-755-4.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al al., senior editors, Bruce G. Wolff ... et (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-387-24846-2.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Marzouk, Deya. "Internal Rectal Intussusception [Internal Rectal Prolapse]". Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Bayless, Theodore M.; Diehl, Anna (2005). Advanced therapy in gastroenterology and liver disease. PMPH-USA. p. 521. ISBN 978-1-55009-248-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Gupta, PJ (2006). "Treatment of rectal mucosal prolapse with radiofrequency coagulation and plication--a new surgical technique". Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 95 (3): 166–71. doi:10.1177/145749690609500307. PMID 17066611.

- ^ "Rectal Prolapse on Pittsburgh Colorectal Surgeons". West Penn Allegheny Health System. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Gaj, F; Trecca, A (July 2005). "Hemorrhoids and rectal internal mucosal prolapse: one or two conditions? A national survey". Techniques in Coloproctology. 9 (2): 163–5. doi:10.1007/s10151-005-0219-0. PMID 16007353.

- ^ Guanziroli, E; Veraldi, S; Guttadauro, A; Rizzitelli, G; Frassani, S (Aug 1, 2011). "Persistent perianal dermatitis associated with mucosal hemorrhoidal prolapse". Dermatitis : Contact, Atopic, Occupational, Drug. 22 (4): 227–9. PMID 21781642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Nonaka, T; Inamori, M; Kessoku, T; Ogawa, Y; Yanagisawa, S; Shiba, T; Sakaguchi, T; Gotoh, E; Maeda, S; Nakajima, A; Atsukawa, K; Takahasi, H; Akasaka, Y (2011). "A case of rectal cancer arising from long-standing prolapsed mucosa of the rectum". Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 50 (21): 2569–73. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5924. PMID 22041358.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Abid, S; Khawaja, A; Bhimani, SA; Ahmad, Z; Hamid, S; Jafri, W (Jun 14, 2012). "The clinical, endoscopic and histological spectrum of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a single-center experience of 116 cases". BMC Gastroenterology. 12 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-12-72. PMC 3444426. PMID 22697798.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fleshman, JW; Kodner, IJ; Fry, RD (December 1989). "Internal intussusception of the rectum: a changing perspective". The Netherlands Journal of Surgery. 41 (6): 145–8. PMID 2694021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pescatori, M; Quondamcarlo, C (November 1999). "A new grading of rectal internal mucosal prolapse and its correlation with diagnosis and treatment". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 14 (4–5): 245–9. doi:10.1007/s003840050218. PMID 10647634.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s al., edited by Tadataka Yamada; associate editors, David H. Alpers ... et (2009). Textbook of gastroenterology (5th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. p. 1725. ISBN 978-1-4051-6911-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Professional Guide to Diseases". Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-7817-7899-2.

- ^ Saleem MM, Al-Momani H (2006). "Acute scrotum as a complication of Thiersch operation for rectal prolapse in a child". BMC Surg. 6: 19. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-6-19. PMC 1785387. PMID 17194301.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Turell, R. (April 1974). "Sexual problems as seen by proctologist". N Y State J Med. 74 (4): 697–8. PMID 4523440.

- ^ Essential Revision Notes in Surgery for Medical Students By Irfan Halim; p139

- ^ Hampton, BS. (January 2009). "Pelvic organ prolapse". Med Health R I. 92 (1): 5–9. PMID 19248418.

- ^ "Trichuris Trichiura". Whipworm. Parasites In Humans.

- ^ a b Mellgren, A; Schultz, I; Johansson, C; Dolk, A (July 1997). "Internal rectal intussusception seldom develops into total rectal prolapse". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 40 (7): 817–20. doi:10.1007/bf02055439. PMID 9221859.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Shorvon, PJ; McHugh, S; Diamant, NE; Somers, S; Stevenson, GW (December 1989). "Defecography in normal volunteers: results and implications". Gut. 30 (12): 1737–49. doi:10.1136/gut.30.12.1737. PMC 1434461. PMID 2612988.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Sherk, Stephanie Dionne. "Rectal prolapse repair on Encyclopedia of Surgery". Encyclopedia of Surgery. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Portier, G; Kirzin, S; Cabarrot, P; Queralto, M; Lazorthes, F (August 2011). "The effect of abdominal ventral rectopexy on faecal incontinence and constipation in patients with internal intra-anal rectal intussusception". Colorectal Disease. 13 (8): 914–7. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02327.x. PMID 20497199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johansson, C; Ihre, T; Ahlbäck, SO (December 1985). "Disturbances in the defecation mechanism with special reference to intussusception of the rectum (internal procidentia)". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 28 (12): 920–4. doi:10.1007/bf02554307. PMID 4064851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Weiss, EG; McLemore, EC (May 2008). "Functional disorders: rectoanal intussusception". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 21 (2): 122–8. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1075861. PMC 2780198. PMID 20011408.

- ^ Dvorkin, LS; Gladman, MA; Epstein, J; Scott, SM; Williams, NS; Lunniss, PJ (July 2005). "Rectal intussusception in symptomatic patients is different from that in asymptomatic volunteers". The British Journal of Surgery. 92 (7): 866–72. doi:10.1002/bjs.4912. PMID 15898121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Christiansen, J; Zhu, BW; Rasmussen, OO; Sørensen, M (November 1992). "Internal rectal intussusception: results of surgical repair". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 35 (11): 1026–8, discussion 1028–9. doi:10.1007/bf02252991. PMID 1425046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Christiansen, J; Hesselfeldt, P; Sørensen, M (May 1995). "Treatment of internal rectal intussusception in patients with chronic constipation". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 30 (5): 470–2. doi:10.3109/00365529509093309. PMID 7638574.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ihre, T; Seligson, U (Jul–Aug 1975). "Intussusception of the rectum-internal procidentia: treatment and results in 90 patients". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 18 (5): 391–6. doi:10.1007/bf02587429. PMID 1149581.

- ^ Dvorkin, LS; Knowles, CH; Scott, SM; Williams, NS; Lunniss, PJ (April 2005). "Rectal intussusception: characterization of symptomatology". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 48 (4): 824–31. doi:10.1007/s10350-004-0834-2. PMID 15785903.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dvorkin, LS; Gladman, MA; Scott, SM; Williams, NS; Lunniss, PJ (July 2005). "Rectal intussusception: a study of rectal biomechanics and visceroperception". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 100 (7): 1578–85. PMID 15984985.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bassotti, G; Villanacci, V; Bellomi, A; Fante, R; Cadei, M; Vicenzi, L; Tonelli, F; Nesi, G; Asteria, CR (March 2012). "An assessment of enteric nervous system and estroprogestinic receptors in obstructed defecation associated with rectal intussusception". Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 24 (3): e155–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01850.x. PMID 22188470.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abendstein, B; Petros, PE; Richardson, PA; Goeschen, K; Dodero, D (May 2008). "The surgical anatomy of rectocele and anterior rectal wall intussusception". International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 19 (5): 705–10. doi:10.1007/s00192-007-0513-7. PMID 18074069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Renzi, A; Talento, P; Giardiello, C; Angelone, G; Izzo, D; Di Sarno, G (October 2008). "Stapled trans-anal rectal resection (STARR) by a new dedicated device for the surgical treatment of obstructed defaecation syndrome caused by rectal intussusception and rectocele: early results of a multicenter prospective study". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 23 (10): 999–1005. doi:10.1007/s00384-008-0522-0. PMID 18654789.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hasan, HM; Hasan, HM (2012). "Stapled transanal rectal resection for the surgical treatment of obstructed defecation syndrome associated with rectocele and rectal intussusception". ISRN Surgery. 2012: 652345. doi:10.5402/2012/652345. PMC 3346690. PMID 22577584.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Goei, R; Baeten, C (January 1990). "Rectal intussusception and rectal prolapse: detection and postoperative evaluation with defecography". Radiology. 174 (1): 124–6. doi:10.1148/radiology.174.1.2294538. PMID 2294538.

- ^ Adusumilli, S; Gosselink, MP; Fourie, S; Curran, K; Jones, OM; Cunningham, C; Lindsey, I (Nov 2013). "Does the presence of a high grade internal rectal prolapse affect the outcome of pelvic floor retraining in patients with faecal incontinence or obstructed defaecation?". Colorectal Disease. 15 (11): e680–5. doi:10.1111/codi.12367. PMID 23890098.

- ^ a b Donald, Kim. "Prolapse and intussusception". ASCRS. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Felt-Bersma, RJ; Tiersma, ES; Cuesta, MA (September 2008). "Rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception, rectocele, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, and enterocele". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 37 (3): 645–68, ix. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.001. PMID 18794001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Festen, S.; Geloven, A. A. W.; D'Hoore, A.; Lindsey, I.; Gerhards, M. F. (8 December 2010). "Controversy in the treatment of symptomatic internal rectal prolapse: suspension or resection?". Surgical Endoscopy. 25 (6): 2000–2003. doi:10.1007/s00464-010-1501-4. PMC 3098348. PMID 21140169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gosselink, MP; Adusumilli, S; Gorissen, KJ; Fourie, S; Tuynman, JB; Jones, OM; Cunningham, C; Lindsey, I (Dec 2013). "Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for fecal incontinence associated with high-grade internal rectal prolapse". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 56 (12): 1409–14. doi:10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a85aa6. PMID 24201396.

- ^ a b Boons, P; Collinson, R; Cunningham, C; Lindsey, I (June 2010). "Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for external rectal prolapse improves constipation and avoids de novo constipation". Colorectal Disease. 12 (6): 526–32. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01859.x. PMID 19486104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gosselink, MP; Adusumilli, S; Harmston, C; Wijffels, NA; Jones, OM; Cunningham, C; Lindsey, I (Dec 2013). "Impact of slow transit constipation on the outcome of laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for obstructed defaecation associated with high grade internal rectal prolapse". Colorectal Disease. 15 (12): e749–56. doi:10.1111/codi.12443. PMID 24125518.

- ^ Samaranayake, CB; Luo, C; Plank, AW; Merrie, AE; Plank, LD; Bissett, IP (June 2010). "Systematic review on ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse and intussusception". Colorectal Disease. 12 (6): 504–12. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01934.x. PMID 19438880.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lenisa, L.; Schwandner, O.; Stuto, A.; Jayne, D.; Pigot, F.; Tuech, J.J.; Scherer, R.; Nugent, K.; Corbisier, F.; Espin-Basany, E.; Hetzer, F. H. (1 October 2009). "STARR with Contour Transtar : prospective multicentre European study". Colorectal Disease. 11 (8): 821–827. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01714.x. PMC 2774156. PMID 19175625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dodi, G; Pietroletti, R; Milito, G; Binda, G; Pescatori, M (October 2003). "Bleeding, incontinence, pain and constipation after STARR transanal double stapling rectotomy for obstructed defecation". Techniques in Coloproctology. 7 (3): 148–53. doi:10.1007/s10151-003-0026-4. PMID 14628157.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bassi, R; Rademacher, J; Savoia, A (December 2006). "Rectovaginal fistula after STARR procedure complicated by haematoma of the posterior vaginal wall: report of a case". Techniques in Coloproctology. 10 (4): 361–3. doi:10.1007/s10151-006-0310-1. PMID 17115306.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sciaudone, G; Di Stazio, C; Guadagni, I; Selvaggi, F (March 2008). "Rectal diverticulum: a new complication of STARR procedure for obstructed defecation". Techniques in Coloproctology. 12 (1): 61–3. doi:10.1007/s10151-008-0389-z. PMID 18512015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Pescatori, M; Gagliardi, G (March 2008). "Postoperative complications after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) and stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures". Techniques in Coloproctology. 12 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1007/s10151-008-0391-0. PMC 2778725. PMID 18512007.

- ^ Boffi, F (June 2008). "Retained staples causing rectal bleeding and severe proctalgia after the STARR procedure". Techniques in Coloproctology. 12 (2): 135–6. doi:10.1007/s10151-008-0412-z. PMID 18545877.

- ^ Lehur, PA; Stuto, A; Fantoli, M; Villani, RD; Queralto, M; Lazorthes, F; Hershman, M; Carriero, A; Pigot, F; Meurette, G; Narisetty, P; Villet, R; ODS II Study, Group (November 2008). "Outcomes of stapled transanal rectal resection vs. biofeedback for the treatment of outlet obstruction associated with rectal intussusception and rectocele: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 51 (11): 1611–8. doi:10.1007/s10350-008-9378-1. PMID 18642046.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mackle, EJ; Parks, TG (October 1986). "The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". Clinics in Gastroenterology. 15 (4): 985–1002. PMID 3536217.

- ^ a b Ertem, D; Acar, Y; Karaa, EK; Pehlivanoglu, E (December 2002). "A rare and often unrecognized cause of hematochezia and tenesmus in childhood: solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". Pediatrics. 110 (6): e79. doi:10.1542/peds.110.6.e79. PMID 12456946.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Womack, NR; Williams, NS; Holmfield, JH; Morrison, JF (October 1987). "Pressure and prolapse--the cause of solitary rectal ulceration". Gut. 28 (10): 1228–33. doi:10.1136/gut.28.10.1228. PMC 1433454. PMID 3678951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Halligan, S; Nicholls, RJ; Bartram, CI (January 1995). "Evacuation proctography in patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: anatomic abnormalities and frequency of impaired emptying and prolapse". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 164 (1): 91–5. doi:10.2214/ajr.164.1.7998576. PMID 7998576.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Van Outryve, MJ; Pelckmans, PA; Fierens, H; Van Maercke, YM (October 1993). "Transrectal ultrasound study of the pathogenesis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". Gut. 34 (10): 1422–6. doi:10.1136/gut.34.10.1422. PMC 1374554. PMID 8244113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Madigan, MR; Morson, BC (November 1969). "Solitary ulcer of the rectum". Gut. 10 (11): 871–81. doi:10.1136/gut.10.11.871. PMC 1553062. PMID 5358578.

- ^ Kang, YS; Kamm, MA; Engel, AF; Talbot, IC (April 1996). "Pathology of the rectal wall in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and complete rectal prolapse". Gut. 38 (4): 587–90. doi:10.1136/gut.38.4.587. PMC 1383120. PMID 8707093.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brosens, LA; Montgomery, EA; Bhagavan, BS; Offerhaus, GJ; Giardiello, FM (November 2009). "Mucosal prolapse syndrome presenting as rectal polyposis". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 62 (11): 1034–6. doi:10.1136/jcp.2009.067801. PMC 2853932. PMID 19861563.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saadah, OI; Al-Hubayshi, MS; Ghanem, AT (2010-08-15). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome presenting as polypoid mass lesions in a young girl". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2 (8): 332–4. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v2.i8.332. PMC 2999680. PMID 21160895.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kang, YS; Kamm, MA; Nicholls, RJ (1995). "Solitary rectal ulcer and complete rectal prolapse: one condition or two?". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 10 (2): 87–90. doi:10.1007/bf00341203. PMID 7636379.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vora, IM; Sharma, J; Joshi, AS (April 1992). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and colitis cystica profunda--a clinico-pathological review". Indian Journal of Pathology & Microbiology. 35 (2): 94–102. PMID 1483723.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Levine, DS (January 1987). ""Solitary" rectal ulcer syndrome. Are "solitary" rectal ulcer syndrome and "localized" colitis cystica profunda analogous syndromes caused by rectal prolapse?". Gastroenterology. 92 (1): 243–53. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(87)90868-7. PMID 3536653.

- ^ Beck, DE (June 2002). "Surgical Therapy for Colitis Cystica Profunda and Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 5 (3): 231–237. doi:10.1007/s11938-002-0045-7. PMID 12003718.

- ^ Gilrane, TB; Orchard, JL; Al-Assaad, ZA (December 1987). "A benign rectal ulcer penetrating into the prostate--diagnosis by prostate-specific antigen". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 33 (6): 467–8. doi:10.1016/s0016-5107(87)71703-9. PMID 2450805.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tseng, CA; Chen, LT; Tsai, KB; Su, YC; Wu, DC; Jan, CM; Wang, WM; Pan, YS (June 2004). "Acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcer syndrome: a new clinical entity? Report of 19 cases and review of the literature". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 47 (6): 895–903, discussion 903–5. doi:10.1007/s10350-004-0531-1. PMC 7177015. PMID 15129312.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yagnik, VD (Jul–Aug 2011). "Massive rectal bleeding: rare presentation of circumferential solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology. 17 (4): 298. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.82592. PMC 3133995. PMID 21727744.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Blackburn, C; McDermott, M; Bourke, B (February 2012). "Clinical presentation of and outcome for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 54 (2): 263–5. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e31823014c0. PMID 22266488.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Umar, SB; Efron, JE; Heigh, RI (2008-09-30). "An interesting case of mistaken identity". Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2 (3): 308–13. doi:10.1159/000154816. PMC 3075189. PMID 21490861.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Amaechi, I; Papagrigoriadis, S; Hizbullah, S; Ryan, SM (November 2010). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome mimicking rectal neoplasm on MRI". The British Journal of Radiology. 83 (995): e221–4. doi:10.1259/bjr/24752209. PMC 3473720. PMID 20965892.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lokuhetty, D; de Silva, MV; Mudduwa, L (December 1998). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) masquerading as a carcinomatous stricture". The Ceylon Medical Journal. 43 (4): 241–2. PMID 10355182.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blanco, F; Frasson, M; Flor-Lorente, B; Minguez, M; Esclapez, P; García-Granero, E (November 2011). "Solitary rectal ulcer: ultrasonographic and magnetic resonance imaging patterns mimicking rectal cancer". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 23 (12): 1262–6. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834b0dee. PMID 21971372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine, DS; Surawicz, CM; Ajer, TN; Dean, PJ; Rubin, CE (November 1988). "Diffuse excess mucosal collagen in rectal biopsies facilitates differential diagnosis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome from other inflammatory bowel diseases". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 33 (11): 1345–52. doi:10.1007/bf01536986. PMID 2460300.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bishop, PR; Nowicki, MJ (June 2002). "Nonsurgical Therapy for Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 5 (3): 215–223. doi:10.1007/s11938-002-0043-9. PMID 12003716.

- ^ van den Brandt-Grädel, V; Huibregtse, K; Tytgat, GN (November 1984). "Treatment of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome with high-fiber diet and abstention of straining at defecation". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 29 (11): 1005–8. doi:10.1007/bf01311251. PMID 6092015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jarrett, ME; Emmanuel, AV; Vaizey, CJ; Kamm, MA (March 2004). "Behavioural therapy (biofeedback) for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome improves symptoms and mucosal blood flow". Gut. 53 (3): 368–70. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.025643. PMC 1773992. PMID 14960517.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vaizey, CJ; Roy, AJ; Kamm, MA (December 1997). "Prospective evaluation of the treatment of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome with biofeedback". Gut. 41 (6): 817–20. doi:10.1136/gut.41.6.817. PMC 1891593. PMID 9462216.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sitzler, PJ; Kamm, MA; Nicholls, RJ; McKee, RF (September 1998). "Long-term clinical outcome of surgery for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". The British Journal of Surgery. 85 (9): 1246–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00854.x. PMID 9752869.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vaizey, CJ; van den Bogaerde, JB; Emmanuel, AV; Talbot, IC; Nicholls, RJ; Kamm, MA (December 1998). "Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome". The British Journal of Surgery. 85 (12): 1617–23. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00935.x. PMID 9876062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lhooq, Michelle (2014-06-17). "Extreme Anal Porn's Shitty Consequences | VICE | United States". VICE. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ "Procidentia on the Free Dictionary". Farlex Inc. Retrieved 14 October 2012.