Amon Göth

- "Göth" and "Goeth" redirect here; see Goeth (surname) for a discussion of this and related surnames.

Amon Leopold Goeth | |

|---|---|

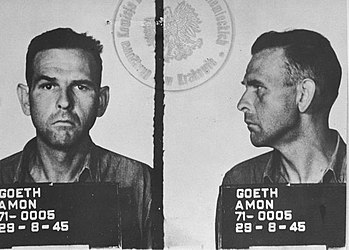

Amon Leopold Goeth's mug shot (1945) | |

| Native name | Amon Leopold Göth |

| Born | 11 December 1908 Vienna, Austria-Hungary (now Austria) |

| Died | 13 September 1946 (aged 37) Kraków, Poland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1930–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | NSDAP #510,764 SS #43,673 |

| Unit | |

| Commands | Arbeitslager KL-Płaszów |

| Spouse(s) |

|

(represented in German as Göth pronounced [ˈɡøːt]) (11 December 1908 – 13 September 1946) was an Austrian SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain) and the commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp in Płaszów in German-occupied Poland during World War II. He was tried as a war criminal after the war by the Supreme National Tribunal of Poland at Kraków and was found guilty of personally ordering the imprisonment, torture, and extermination of individuals and groups of people. He was also convicted of homicide, the first such conviction at a war crimes trial, for "personally killing, maiming and torturing a substantial, albeit unidentified number of people".[1] He was executed by hanging not far from the former site of the Płaszów camp. The film Schindler's List (1993) depicts his practice of shooting camp internees.

Early life and career

Goeth was born on 11 December 1908 in Vienna, then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to a family in the book publishing industry.[2] Goeth joined a Nazi youth group at age 17 and was a member of the antisemitic nationalist paramilitary group Heimwehr (Home Guard) from 1927 to 1930. He dropped his membership to join the Austrian branch of the Nazi Party, being assigned the party membership number 510,764 in September 1930. Goeth joined the Austrian SS in 1930 and was appointed an SS-Mann with the SS number 43,673.[3]

Goeth served with the SS Truppe Deimel and Sturm Libardi in Vienna until January 1933, when he was promoted to serve as adjutant and platoon leader of the 52nd SS-Standarte, a regimental-sized unit. He was soon promoted to SS-Scharführer (squad leader).[4] He fled to Germany when his illegal activities, including obtaining explosives for the Nazi Party, made him a wanted man. The Austrian Nazi Party was declared illegal in Austria on 19 June 1933, so they set up operations in exile in Munich. From this base, Goeth smuggled radios and weapons into Austria and acted as a courier for the SS. [5] He was arrested in October 1933 by the Austrian authorities and was released for lack of evidence in December 1933. He was again detained after the assassination of Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in a failed Nazi coup attempt in July 1934. He escaped custody and fled to the SS training facility at Dachau, next to the infamous Dachau Concentration Camp.[5] He temporarily quit the SS and Nazi party activities until 1937 and lived in Munich while trying to help his parents to develop their publishing business. He married on the recommendation of his parents, but was divorced after only a few months.[6]

Goeth returned to Vienna shortly after the Anschluss in 1938 and resumed his party activities. He married Anny Geiger in a civil SS ceremony on October 1938. The couple had three children, Peter, born in 1939, who died of diphtheria at age 7 months,[7] Werner, born in 1940, and a daughter, Ingeborg, born in 1941.[8] The couple maintained a permanent home in Vienna throughout World War II.[9] Initially assigned to 89th SS-Standarte, Goeth was transferred to the 1st SS-Sturmbann of the 11th SS-Standarte at the start of the war and was promoted to SS-Oberscharführer (staff sergeant) in early 1941. He soon gained a reputation as a seasoned administrator in the Nazi efforts to isolate and relocate the Jewish population of Europe as an Einsatzführer (action leader) and financial officer for the Reichskommissariat für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums (Reichskommissariat for the Strengthening of German Nationhood; RKFDV). He was commissioned to the rank of SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) on 14 July 1941.[10]

He was transferred to Lublin in the summer of 1942, where he joined the staff of SS-Brigadeführer Odilo Globočnik, the SS and Police Leader of the Kraków area, as part of Operation Reinhard, the code name given to the establishment of the three extermination camps at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka. Nothing is known of his activities in the six months he served with Operation Reinhard; participants were sworn to secrecy. But according to the transcripts of his later trial, Goeth was responsible for rounding up and transporting victims to these camps to be killed.[11]

Płaszów

Goeth was assigned to the SS-Totenkopfverbände ("Deaths-head" unit; concentration camp service). His first assignment, starting on 11 February 1943, was to oversee the construction of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp, which he was to command.[12] The camp took one month to construct using forced labour. On 13 March 1943, the Jewish ghetto of Kraków was liquidated and those still fit for work were sent to the new camp at Płaszów.[13] Several thousand not deemed fit for work were sent to extermination camps and killed. Hundreds more were killed on the streets by the Nazis as they cleared out the ghetto.[14]

On 3 September 1943, in addition to his duties at Płaszów, Goeth was the officer in charge of the liquidation of the ghetto at Tarnów, which had been home to 25,000 Jews (about 45 per cent of the city's population) at the start of World War II. By the time the ghetto was liquidated, 8,000 Jews remained. They were loaded on a train to Auschwitz concentration camp, but less than half survived the journey. Most of the survivors were deemed unsuitable for forced labour and were killed immediately on their arrival at Auschwitz. According to testimony of several witnesses as recorded in his 1946 indictment for war crimes, Goeth personally shot between 30 and 90 women and children during the liquidation of the ghetto.[15]

Goeth was also the officer in charge of the liquidation of Szebnie concentration camp, which interned 4,000 Jewish and 1,500 Polish slave labourers. Evidence presented at Goeth's trial indicates he delegated this task to a subordinate, SS-Hauptscharführer Josef Grzimek, who was sent to assist camp commandant SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Kellermann with mass executions.[16][17] Between 21 September 1943 and 3 February 1944 the camp was gradually liquidated. Around a thousand of the victims were taken to the nearby forest and shot, and the remainder were sent to Auschwitz, where most were gassed immediately on arrival.[16]

By April 1944, Goeth had been promoted to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain), having received a double promotion, skipping the rank of SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant).[18] He was also appointed a reserve officer of the Waffen-SS.[19] In early 1944 the status of the Kraków-Płaszów Labour Camp changed to a permanent concentration camp under the direct authority of the SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt (WVHA; SS Economics and Administration Office).[20] Mietek Pemper[a] testified at the trial that it was during the earlier period that Goeth committed most of the random and brutal killings for which he became notorious.[22] Concentration camps were more closely monitored by the SS than labour camps, so conditions improved slightly when the designation was changed.[23]

The camp housed about 2,000 inmates when it opened. At its peak of operations in 1944, a staff of 636 guards oversaw 25,000 permanent inmates, and an additional 150,000 people passed through the camp in its role as a transit camp.[24] Goeth personally murdered prisoners on a daily basis. His two dogs, Rolf and Ralf, were trained to tear inmates to death.[20] He shot people from his window of his office if they appeared to be moving too slowly or resting in the yard.[20] He shot to death a Jewish cook because the soup was too hot.[25] He brutally mistreated his two maids, Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig and Helen Hirsch, who were in constant daily fear for their lives, as were all the inmates.[26]

As a survivor I can tell you that we are all traumatized people. Never would I, never, believe that any human being would be capable of such horror, of such atrocities. When we saw him from a distance, everybody was hiding, in latrines, wherever they could hide. I can't tell you how people feared him.

— Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig[27]

Poldek Pfefferberg, another Schindlerjude (Schindler Jew), said: "When you saw Goeth, you saw death."[28] Yet Goeth spared the life of Jewish prisoner Natalia Hubler (later known as Natalia Karp) and that of her sister, after hearing her play a nocturne by Chopin on the piano the day after she arrived at the Płaszów camp.[29]

Goeth believed if one member of a work team escaped or committed some infraction, the entire team must be punished. On one occasion he ordered every second member of a work detail should be shot because one of the party had escaped.[30] On another occasion he personally shot every fifth member of a crew because one had not returned to the camp.[31] The main execution site at Płaszów was Hujowa Górka ("Prick Hill"), a large hill that was used for mass killings and executions.[32] Pemper testified that 8,000 to 12,000 people were murdered at Płaszów.[33]

Dismissal and capture

On 13 September 1944 Goeth was relieved of his position and charged by the SS with theft of Jewish property (which belonged to the state, according to Nazi legislation), failure to provide adequate food to the prisoners under his charge, violation of concentration camp regulations regarding the treatment and punishment of prisoners, and allowing unauthorised access to camp personnel records by prisoners and non-commissioned officers.[34] Administration of the camp at Płaszów was turned over to SS-Obersturmführer Arnold Büscher. Goeth was scheduled for an appearance before SS judge Georg Konrad Morgen, but due to the progress of World War II and Germany's looming defeat, the charges against him were dropped in early 1945.[35] SS doctors diagnosed Goeth as suffering from mental illness and he was committed to a mental institution in Bad Tölz, where he was arrested by the United States military in May 1945.[36]

Trial and execution

After the war, Goeth was extradited to Poland, where he was tried by the Supreme National Tribunal of Poland in Kraków between 27 August and 5 September 1946.[1][36] Goeth was found guilty of membership in the Nazi Party (which had been declared a criminal organisation) and personally ordering the imprisonment, torture, and extermination of individuals and groups of people.[1] He was also convicted of homicide, the first such conviction at a war crimes trial, for "personally killing, maiming and torturing a substantial, albeit unidentified number of people".[1] He was sentenced to death and was hanged on 13 September 1946 at the Montelupich Prison in Kraków, not far from the site of the Płaszów camp.[37] Goeth's last words were "Heil Hitler".[38] The body was cremated and the ashes thrown in the Vistula River.[39]

Family

In addition to his two marriages, Goeth had a two-year relationship with Ruth Irene Kalder, a beautician and aspiring actress originally from Breslau (or Gleiwitz; sources vary).[40] Kalder first met Goeth in 1942 or early 1943, when she worked as a secretary at Oskar Schindler's enamelware factory in Kraków. She soon moved in with Goeth and the two had an affair. She took Goeth's name shortly after his death.[41] Goeth's last child was a daughter, Monika Hertwig, whom he had by Kalder. Monika was born in November 1945 in Bad Tölz.

In media and culture

Schindler's List

Goeth's actions at Płaszów Labour Camp became internationally known through his depiction by British actor Ralph Fiennes in the 1993 film Schindler's List. In a subsequent interview, Fiennes recalled:

People believe that they’ve got to do a job, they’ve got to take on an ideology, that they’ve got a life to lead; they’ve got to survive, a job to do, it’s every day inch by inch, little compromises, little ways of telling yourself this is how you should lead your life and suddenly then these things can happen. I mean, I could make a judgement myself privately, this is a terrible, evil, horrific man. But the job was to portray the man, the human being. There’s a sort of banality, that everydayness, that I think was important. And it was in the screenplay. In fact, one of the first scenes with Oskar Schindler, with Liam Neeson, was a scene where I’m saying, 'You don’t understand how hard it is, I have to order so many—so many metres of barbed wire and so many fencing posts and I have to get so many people from A to B.' And, you know, he’s sort of letting off steam about the difficulties of the job.[42]

Fiennes won a BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[43] His portrayal ranked 15th on American Film Institute's list of the top 50 film villains of all time. He ranks as the highest non-fiction villain.[44] When Płaszów survivor Mila Pfefferberg was introduced to Fiennes on the set of the film, she began to shake uncontrollably, as Fiennes, attired in full SS dress uniform, reminded her of the real Amon Goeth.[45]

Monika Hertwig

In 2002, Goeth's daughter Monika Hertwig published her memoirs under the title Ich muß doch meinen Vater lieben, oder? ("But I have to love my father, don't I?"). Hertwig described the subsequent life of her mother, Ruth Kalder Goeth, who unconditionally glorified her fiancé until confronted with his role in the Holocaust. Ruth committed suicide in 1983, shortly after giving an interview in Jon Blair's documentary Schindler.[46] Hertwig's experiences in dealing with her father's crimes are detailed in Inheritance, a 2006 documentary directed by James Moll. Appearing in the documentary is Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig, one of Goeth's former housemaids. The documentary details the meeting of the two women at the Płaszów memorial site in Poland.[47] Hertwig had requested the meeting, but Jonas-Rosenzweig was hesitant because her memories of Goeth and the concentration camp were so traumatic. She eventually agreed after Hertwig wrote to her, "We have to do it for the murdered people."[27] Jonas felt touched by this sentiment and agreed to meet her.[27]

In a subsequent interview, Jonas-Rosenzweig recalled:

It's hard for me to be with her because she reminds me a lot of, you know ... she's tall, she has certain features. And I hated him so. But she is a victim. And I think it's important because she is willing to tell the story in Germany. She told me people don't want to know, they want to go on with their lives. And I think it's very important because there's a lot of children of perpetrators, and I think she's a brave person to go on talking about it, because it's difficult. And I feel for Monika. I am a mother, I have children. And she is affected by the fact that her father was a perpetrator. But my children are also affected by it. And that's why we both came here. The world has to know, to prevent something like this from happening again.[27]

Hertwig also appeared in a documentary called Hitler's Children (2011), directed and produced by Chanoch Zeevi, an Israeli documentary filmmaker. In the documentary, Hertwig and other close relatives of infamous Nazi leaders describe their feelings, relationships, and memories of their relatives.[48]

Jennifer Teege

Jennifer Teege, the daughter of Monika Hertwig and a Nigerian, discovered that Goeth was her grandfather through Hertwig's 2002 memoirs. She addressed her coming to terms with her origins in a 2013 book, Amon. Mein Großvater hätte mich erschossen ("My grandfather would have shot me").[49]

Summary of SS career

- SS number: 43673

- Nazi Party number: 510764

- Primary positions: Lagerkommandant, Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp

- Waffen-SS service: SS-Hauptsturmführer der Reserve[19]

Dates of rank

- SS-Mann: 1930

- SS-Scharführer: c.1935

- SS-Oberscharführer: 1941

- SS-Untersturmführer: 14 July 1941

- SS-Hauptsturmführer: 1 August 1943

- SS-Hauptsturmführer der Reserve der Waffen-SS: 20 April 1944[19]

Awards

At the time of his capture by American forces, Goeth claimed to have been recently promoted to the rank of Sturmbannführer, a claim not supported in his SS service record. Nonetheless, several American interrogation transcripts list him as "SS-Major Goeth". SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp, supported the claim at his own trial when he testified that Goeth was a major in the concentration camp service. Due to poor record keeping at the end of the war, it is possible that Goeth was promoted; most historical accounts simply list his rank as that of Hauptsturmführer.[50][51]

Notes

- ^ Mieczysław "Mietek" Pemper, who was Jewish, was forced to work as Goeth's personal secretary and stenographer in Płaszów. Using names provided by Jewish Ghetto Police officer Marcel Goldberg, Pemper compiled and typed the list of 1,200 Jews whose lives were saved when they were sent to Oskar Schindler's factory in Brünnlitz in October 1944.[21]

Citations

- ^ a b c d Rzepliñski 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 217.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 220.

- ^ a b Crowe 2004, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 221–223.

- ^ Sachslehner 2008, p. 41. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSachslehner2008 (help)

- ^ Sachslehner 2008, p. 43. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSachslehner2008 (help)

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 210, 223.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 224–226.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 227.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 376.

- ^ Roberts 1996, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 232.

- ^ a b Crowe 2004, pp. 234–236.

- ^ Bracik & Twaróg 2003.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 233.

- ^ a b c d SS service record.

- ^ a b c Crowe 2004, p. 256.

- ^ Mietek Pemper obituary.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 242.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 317.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 237, 242.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 257.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 259–264.

- ^ a b c d Fishman 2009.

- ^ Keneally 1993, p. 360.

- ^ Natalia Karp obituary.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 258.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 259.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 265.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 237.

- ^ Crowe 2004, pp. 354–355.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 359.

- ^ a b McKale 2012, p. 201.

- ^ Museum of the Polish Army.

- ^ Teege & Sellmair 2013, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 211.

- ^ Sachslehner 2008, p. 167. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSachslehner2008 (help)

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 210.

- ^ Fiennes 2010.

- ^ Freud 2012.

- ^ American Film Institute 2003.

- ^ Corliss 1994.

- ^ Jackson 2009.

- ^ PBS, Inheritance.

- ^ IDFA 2011.

- ^ Schaaf 2013.

- ^ Fitzgibbon 2000, p. [page needed].

- ^ Höss 1996, p. [page needed].

References

- "27 August 1946: Polish tribunal sentenced SS-Hauptsturmführer Göth to death by hanging". Major events after May 9, 1945 (in Polish). Muzeum Wojska Polskiego (Museum of the Polish Army). Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains". AFI.com. American Film Institute. 4 June 2003. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Bracik, Jacek; Twaróg, Józef (2003). "Obóz w Szebniach". Region Jasielski (in Polish). 39 (3). Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

Oberscharführer Josef Grzimek conducted mass extermination actions at the Dobrucowa Forest outside Szebnie in the fall and winter of 1943.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Corliss, Richard (21 February 1994). "The Man Behind the Monster". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crowe, David M. (2004). Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-465-00253-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fiennes, Ralph (4 March 2010). "Voices on Antisemitism – A Podcast Series". ushmm.org. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fishman, Aleisha (February 26, 2009). "Helen Jonas, the Holocaust Survivor". Voices on Antisemitism — A Podcast Series. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fitzgibbon, Constantine (2000). Commandant of Auschwitz : The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess. London: Phoenix Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Freud, Emma (9 January 2012). "Ralph Fiennes: In Conversation". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Hitler's Children". International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Höss, Rudolf (1996). Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz. New York: Da Capo Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Inheritance". POV. Public Broadcasting Service. 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Jackson, Livia Bitton (8 July 2009). "Monika Goeth: In The Shadow Of Evil". JewishPress.com. The Jewish Press. Archived from the original (Cached by Zoom) on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keneally, Thomas (1993) [1982]. Schindler's List. New York: Touchstone. ISBN 0-671-88031-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKale, Donald M. (2012). Nazis after Hitler: How Perpetrators of the Holocaust Cheated Justice and Truth. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-1316-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roberts, Jack L. (1996). The Importance of Oskar Schindler. The Importance of ... Biography Series. San Diego: Lucent. ISBN 1-56006-079-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rzepliñski, Andrzej (25 March 2004). "Prosecution of Nazi Crimes in Poland in 1939–2004" (PDF). First International Expert Meeting on War Crimes, Genocide, and Crimes against Humanity. Lyon, France: International Criminal Police Organization – Interpol General Secretariat. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sachslehner, Johannes (2008). Kalder Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Wien: Leben und Taten des Amon Leopold Göth (in German). Wien: Styria Verlag. ISBN 978-3-222-13233-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Schaaf, Julia (14 September 2013). "Jennifer Teege: Ich bin mehr". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 20 September 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Staff (15 June 2011). "Mietek Pemper". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Staff (11 July 2007). "Natalia Karp". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- SS service record of Amon Göth, College Park, Maryland: National Archives and Records Administration.

- Teege, Jennifer; Sellmair, Nikola (2013). Amon: Mein Großvater hätte mich erschossen (in German). Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. ISBN 978-3-498-06493-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Sachslehner, Johannes (2008). Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Wien (in German). Wien: Styria Verlag. ISBN 978-3-222-13233-9.

External links

- 1908 births

- 1946 deaths

- People from Vienna

- Austrian people convicted of crimes against humanity

- Austrian people executed abroad

- Austrian people executed by hanging

- Executed Austrian Nazis

- Executed Nazi concentration camp personnel

- Filmed executions

- Holocaust perpetrators

- Kraków Ghetto

- Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp personnel

- Nazi concentration camp commandants

- Nazis executed in Poland

- Oskar Schindler

- People executed by Poland by hanging

- SS officers

- Austrian people convicted of murder