Ancient Egypt in the Western imagination

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

It has been suggested that Egyptomania be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since March 2014. |

Egypt has loomed large in the Western imagination in the Greek and Hebrew traditions. Egypt was already ancient to outsiders, and the idea of Egypt, as a figment of the Western imagination, has continued to be at least as influential in the history of ideas as the actual historical Egypt itself.[1] All Egyptian culture was transmitted to Roman and post-Roman European culture through the lens of Hellenistic conceptions of it, until the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics by Jean-François Champollion in the 1820s rendered Egyptian texts legible.

After Late Antiquity, the Old Testament image of Egypt as the land of enslavement for the Hebrews predominated, and "Pharaoh" became a synonym for despotism and oppression in the 19th century. However, Enlightenment thinking and colonialist explorations in the late 18th century renewed interest in ancient Egypt as both a model for, and an exotic alternative to, Western culture, particularly as a Romantic source for classicizing architecture.

Antiquity

Classical texts

Herodotus, in his Histories, Book II, gives a detailed if selectively coloured and imaginative description of ancient Egypt. He praises peasants' preservation of history through oral tradition, and Egyptians' piety. He lists the many animals to which Egypt is home, including the mythical phoenix and winged serpent, and gives inaccurate descriptions of the hippopotamus and horned viper. Herodotus was quite critical about the stories he heard from the priests (II,123), but successors were more gullible, like Diodorus Siculus who visited Hellenistic Egypt in the 1st century BCE, where he was told by priests that many famous Greek philosophers had studied in Egypt. Unable to speak Egyptian, and unable to read hieroglyphs, the Greek visitors were eager and uncritical believers of whatever the priests, translators, or guides told them, and they were glad to note down that their Greek civilisation descended from an even more ancient one. As time went by, the Egyptians understood better what the Greeks wanted to hear, and the stories became ever more fanciful, and the priests' list of famous Greeks having studied in Egypt became longer. By the time Plutarch writes about Egypt, even Lycurgus has visited the place. Both Plutarch and Diogenes Laertius (3rd century) mention that Thales studied in Egypt, whilst nothing is really known about Thales from his own time. Iamblichus of Chalcis in the 3rd century CE reports that Pythagoras studied in Egypt for 22 years.

From the classical texts that thus evolved, a mythical Egypt emerges as the mother-country of Religion, Wisdom, Philosophy, and Science.

Among the Romans, an Egypt that had been drawn into the Roman economic and political sphere was still a source of wonders: Ex Africa semper aliquid novi;[2] the exotic fauna of the Nile is embodied in the famous "Nilotic" mosaic from Praeneste, and Romanized iconographies were developed for the "Alexandrian Triad", Isis, who developed a widespread Roman following, for Harpocrates, misconstrued as a "god of silence", and for the Ptolemaic syncretism of Serapis.[3]

The Bible

Egypt is mentioned 611 times in the Bible, between Genesis 12:10 and Revelation 11:8.[4] The Septuagint, through which most Christians knew the Hebrew Bible, was commissioned in Alexandria, it was remembered, with the embellishment that though the seventy scholars set to work upon the texts independently, miraculously each arrived at the same translation.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Following the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Egypt, the West lost direct contact with Egypt and its culture. In Medieval Europe, Egypt was depicted primarily in the illustration and interpretation of the biblical accounts. These illustrations were often quite fanciful, as the iconography and style of ancient Egyptian art, architecture and costume were largely unknown in the West (illustration, right). Dramatic settings of the Plagues of Egypt, the Parting of the Red Sea and the story of Joseph in Egypt, and from the New Testament the Flight into Egypt figured large in medieval illuminated manuscripts. Biblical hermeneutics were primarily theological in nature, and had little to do with historical investigations. Throughout the Middle Ages "mummy", made, if it were genuine, by pounding mummified bodies, was a standard product of apothecary shops.[5]

During the Renaissance the German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher gave a fanciful allegorical "decipherment" of hieroglyphs, and Egypt was thought of as a source of ancient mystic or occult wisdom. In alchemist circles, the prestige of "Egyptians" rose. A few astute scholars, however, were not to be fooled:[6] in the 16th century, Isaac Casaubon unmasked the Corpus Hermeticum of the great Hermes Trismegistus as the work of a Greek writer of about the 4th century CE.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

18th century

The 18th century witnessed the rise of a first authentically historicist imagination, one that attempted to picture the cultures of the distant past as truly different in kind, not merely in curious detail and superstitious idolatry. Early in the century, Jean Terrasson had written Sethos, a work of fiction, which launched the notion of Egyptian mysteries. In an atmosphere of antiquarian interest, a sense arose that ancient knowledge was somehow embodied in Egyptian monuments and lore. Following the Rosicrucian example, an Egyptian imagery pervaded the European Freemasonry of the time and its imagery, such as the eye on the pyramid — still depicted on the Great Seal of the United States (1782), which appears on the United States one-dollar bill — and the Egyptian references in Mozart's Masonic-themed Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute, 1791), and his earlier unfinished "Thamos".[citation needed]

The revival of curiosity about the Antique world, seen through written documents, spurred the publication of a collection of Greek texts that had been assembled in Late Antiquity, which were published as the corpus of works of Hermes Trismegistus. But the broken ruins that appeared in settings of the newly prominent iconic episode of the "Rest on the Flight into Egypt" were always of Roman character.

With historicism came the first fictions set in the Egypt of the imagination. Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra had been set partly in Alexandria, but its protagonists were noble and universal, and Shakespeare had not been concerned to evoke local color.

19th century

The rationale for "Egyptomania" rests on a similar concept: Westerners looked to ancient Egyptian motifs because ancient Egypt itself was intrinsically so alluring. The Egyptians used to consider their religion and their government somewhat eternal; they were supported in this thought by the enduring aspect of great public monuments which lasted forever and which appeared to resist the effects of time. Their legislators had judged that this moral impression would contribute to the stability of their empire.[7]

The culture of Romanticism embraced every exotic locale, and its rise in the popular imagination coincided with Napoleon's failed Egyptian campaign. A modern "Battle of the Nile" could hardly fail to stir renewed curiosity about Egypt beyond the figure of Cleopatra. At about the same moment, the tarot captured the imagination of the Frenchman Antoine Court de Gebelin, who brought it to Europe's attention as a purported key to the occult knowledge of Egypt. All this gave rise to "Egyptomania" and occult tarot.

This Egypt of the imagination came to grief with the 1824 decryption of hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion. Inscriptions that a century earlier had been thought to hold occult wisdom, proved to be nothing more than royal names and titles, funerary formulae, boastful accounts of military campaigns. The explosion of new knowledge about actual Egyptian religion, wisdom and philosophy exposed the mythical image of Egypt as an illusion that had been created by the Greek and Western imaginations.

On the most popular 19th-century level, all of ancient Egypt was reduced in the European imagination to the Nile, the Pyramids and the Great Sphinx in a setting of sand, characterized on a more literary level in the English poet Shelley's "Ozymandias" (1818):

round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Egyptian Revival architecture extended the repertory of classical design explored by the Neoclassical movement and widened the decorative vocabulary that could be drawn upon.

The well-known Egyptian cult of the dead inspired the Egyptian Revival themes first employed in Highgate Cemetery, near London, which was opened in 1839 by a company founded by the designer-entrepreneur Stephen Geary (1797–1854); its architectural features, which included a 'Gothic Catacomb' as well as an 'Egyptian Avenue', were brought to public attention once more by James Stevens Curl.[8]

Ancient Egypt provided the setting for the Italian composer Verdi's stately 1871 opera Aida, commissioned by the Europeanized Khedive for premiere in Cairo.

In 1895 the Polish writer Bolesław Prus completed his only historical novel, Pharaoh, a study of mechanisms of political power, described against the backdrop of the fall of the Twentieth Dynasty and the New Kingdom. It is, at the same time, one of the most compelling literary reconstructions of life at every level of ancient Egyptian society. In 1966 the novel was adapted as a Polish feature film.[9]

20th century

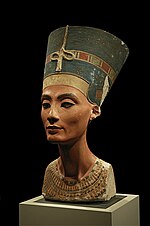

In 1912, the discovery of an exquisite painted limestone bust of Nefertiti, unearthed from its sculptor's workshop near the royal city of Amarna, added the first new celebrity of Egypt. The bust, now in Berlin's Egyptian Museum became so famous through the medium of photography that it became the most familiar, most copied work of ancient Egyptian sculpture; Nefertiti's strong-featured profile was a notable influence on new ideals of feminine beauty in the 20th century.

The 1922 discovery of the undamaged tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun introduced a new celebrity to join Nefertiti — "King Tut". The tomb's spectacular treasures influenced Art-Deco design vocabulary. Also, for many years there persisted rumors, probably tabloid-inspired, of a "curse"; the rumors focused on the alleged premature deaths of some of those who had first entered the tomb. A recent study of journals and death records, however, indicates no statistical difference between the ages at death of those who had entered the tomb and of expedition members who had not; indeed, most of the individuals lived past age 70. The idea of a "mummy's curse" inspired films such as The Mummy, starring Boris Karloff, which popularized the idea of ancient Egyptian mummies reanimating as monsters. Another literary occurrence at that time of Egypt is Agatha Christie's 1936 mystery novel Death on the Nile.

Hollywood's Egypt is a major contributor to the fantasy Egypt of modern culture. The cinematic spectacle of Egypt climaxed in sequences of Cecil B. deMille's The Ten Commandments (1956) and in Jeanne Crain's Nefertiti in the 1961 Italian Cinecittà production of Queen of the Nile, and collapsed with the failure of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963).

In 1978, Tutankhamun was commemorated in the whimsical song, "King Tut", by American comedian Steve Martin, and in 1986 the poses in some Egyptian mural art were evoked in the song "Walk Like an Egyptian" by The Bangles.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art resurrected the Temple of Dendur within its own quarters in 1978. In 1989 the Louvre raised its own glass pyramid, and in 1993 Las Vegas's Luxor Hotel opened with its replica tomb of Tutankhamen.

A best-selling series of novels by French author and Egyptologist Christian Jacq was inspired by the life of Pharaoh Ramses II ("the Great").

21st century

HBO's miniseries Rome features several episodes set in Greco-Roman Egypt. The faithful reconstructions of an ancient Egyptian court (as opposed to the historically correct Hellenistic culture) were built in Rome's Cinecittà studios. The series depicts dramatized accounts of the relations among Cleopatra, Ptolemy XIII, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Cleopatra is played by Lyndsey Marshal, and much of the second season is dedicated to events building up to the famous suicides of Cleopatra and her lover Mark Antony in 30 BCE.

La Reine Soleil, a 2007 animated film by Philippe Leclerc, features Akhenaten, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun), Akhesa (Ankhesenepaten, later Ankhesenamun), Nefertiti, and Horemheb in a complex struggle pitting the priests of Amun against Akhenaten's intolerant monotheism.

Notes

- ^ Janetta Rebold Benton and"Ancient Egypt in the European imagination" p. 54ff. Robert DiYanni, Arts and Culture: an introduction to the humanities, 1999: "Ancient Egypt in the European imagination", pp 54ff.

- ^ An overview is M. J. Versluys, Aegyptiaca Romana: nilotic scenes and the Roman views of Egypt, 2002.

- ^ Isis: Laurent Bricault, M. J. Versluys, P. G. P. Meyboom, eds. Nile into Tiber: Egypt in the Roman world: proceedings of the IIIrd International Conference of Isis Studies (Leiden), May 11-14, 2005; Harpocrates: Iconography of Harpocrates (PDF-article); Serapis: Anne Roullet, The Egyptian and Egyptianizing monuments of imperial Rome, 1972.

- ^ Strong, James (2001). Strong's Expanded Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0-7852-4540-5.

- ^ "Mummy". Encyclopædia Britannica Concise. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ^ Johann Kestler enumerated the contemporary critics of Kircher: "Some critics, Kestler wrote with amazement, believed that Kircher's explanation of the hieroglyphs was simply 'a figment of his own mind'" (Paula Findlen, Athanasius Kircher: the last man who knew everything, 2004:38)

- ^ Reprinted in Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac, Fourier et Napoleon: l'Egypte et les cent jours: memoires et documents inedits, Paris, Firmin Didot Freres, 1844, p. 170.

- ^ James Stevens Curl, The Victorian Celebration of Death, 1972, pp. 86-102.

- ^ Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' Pharaoh: the Creation of a Historical Novel", The Polish Review, 1994, no. 1, pp. 45-50.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan, Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-674-58738-3.

- Breasted, James Henry, A History of Egypt from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, with Illustrations and Maps, New York, Bantam Books, 1967.

- Curl, James Stevens, The Egyptian Revival, revised and enlarged edition, New York, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-36119-2 (paperback alkaline paper), ISBN 0-415-36118-4 (hardback alkaline paper).

- Herodotus, The Histories, Newly translated and with an Introduction by Aubrey de Sélincourt, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1965.