Anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism refers to historical movements that oppose the clergy for reasons including their actual or alleged power and influence in all aspects of public and political life and their involvement in the everyday life of the citizen, their privileges, or their enforcement of orthodoxy.[1]

Not all anti-clericals are irreligious or anti-religious, some have been religious and have opposed clergy on the basis of institutional issues and/or disagreements in religious interpretation, such as during the Protestant Reformation.

Europe

France

Revolution

The French Revolution, particularly in its Jacobin period, initiated one of the most violent episodes of anti-clericalism in modern Europe as a reaction against the dominant role of the Catholic church in pre-revolutionary France; the new revolutionary authorities suppressed the church; destroyed, desecrated and expropriated monasteries; exiled 30,000 priests and killed hundreds more.[2] As part of a campaign to de-Christianize France in October 1793 the Christian calendar was replaced with one reckoning from the date of the Revolution, and an atheist Cult of Reason was inaugurated, all churches not devoted to that cult being closed.[3] In 1794, the atheistic cult was replaced with a deistic Cult of the Supreme Being.[3] When anticlericalism became a clear goal of French revolutionaries, counter-revolutionaries seeking to restore tradition and the Ancien Régime took up arms, particularly in the War in the Vendée (1793 to 1796).

When Pope Pius VI took sides against the revolution in the First Coalition (1792–1797), Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Italy (1796).[4] French troops imprisoned the Pope in 1797, and he died after six weeks of captivity.[4] After a change of heart, Napoleon then re-established the Catholic Church in France with the signing of the Concordat of 1801,[4] and banned the Cult of the Supreme Being. Many anti-clerical policies continued. When Napoleonic armies entered a territory, monasteries were often sacked and church property secularized.[5][6][7][8]

Third Republic

A further phase of anti-clericalism occurred in the context of the French Third Republic and its dissensions with the Catholic Church. Prior to the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, the Catholic Church enjoyed preferential treatment from the French state (formally along with the Jewish, Lutheran and Calvinist minority religions, but in practice with much more influence than those). During the 19th century, public schools employed primarily priests as teachers, and religion was taught in schools (teachers were also obliged to lead the class to Mass). In 1881–1882 Jules Ferry's government passed the Jules Ferry laws, establishing free education (1881) and mandatory and lay education (1882), giving the basis of French public education. The Third Republic (1871–1940) firmly established itself after the 16 May 1877 crisis triggered by the Catholic Legitimists who dreamed of a return to the Ancien Régime.

In 1880 and 1882 Benedictine teaching monks were effectively exiled. This was not completed until 1901.[9][10][11][12][13]

The 1905 law on separation of state and church was enacted with strength and vigor by the government of Radical-Socialist Émile Combes. Most Catholic schools and educational foundations were closed — except in Alsace-Lorraine which at that time was part of Germany.

In the Affaire Des Fiches in France in 1904–1905, it was discovered that the anticlerical War Minister of the Combes government, General Louis André, was determining promotions based on the French Masonic Grand Orient's huge card index on public officials, detailing which were Catholic and who attended Mass, with a view to preventing their promotions.[14]

Republicans' anti-clericalism softened after the First World War as the Catholic right-wing began to accept the Republic and secularism. However, the theme of subsidized private schools in France, which are overwhelmingly Catholic but whose teachers draw pay from the state, remains a sensitive issue in French politics.

Austria (Holy Roman Empire)

Emperor Joseph II (emperor 1765-1790) opposed what he called “contemplative” religious institutions — reclusive Catholic institutions that he perceived as doing nothing positive for the community.[15] His policy towards them are included in what is called Josephinism.

Joseph decreed that Austrian bishops could not communicate directly with the Curia. More than 500 of 1,188 monasteries in Austro-Slav lands (and a hundred more in Hungary) were dissolved, and 60 million florins taken by the state. This wealth was used to create 1,700 new parishes and welfare institutions.[16]

The education of priests was taken from the Church as well. Joseph established six state-run “General Seminaries.” In 1783, a Marriage Patent treated marriage as a civil contract rather than a religious institution.[17]

Catholic Historians have claimed that there was an alliance between Joseph and anti-clerical Freemasons.[18]

Germany

The Kulturkampf, literally "culture struggle") refers to German policies in reducing the role and power of the Catholic Church in Prussia, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck.

Bismarck accelerated the Kulturkampf, which did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria (where Catholics were in a majority). As one scholar put it, "the attack on the church included a series of Prussian, discriminatory laws that made Catholics feel understandably persecuted within a predominantly Protestant nation." Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans and other orders were expelled in the culmination of twenty years of anti-Jesuit and antimonastic hysteria.[19]

In 1871, the Catholic Church comprised 36.5% of the population of the German Empire, including millions of Germans in the west and South, as well as the vast majority of Poles. In this newly founded Empire, Bismarck sought to appeal to liberals and Protestants (62% of the population) by reducing the political and social influence of the Catholic Church.

Priests and bishops who resisted the Kulturkampf were arrested or removed from their positions. By the height of anti-Catholic measures, half of the Prussian bishops were in prison or in exile, a quarter of the parishes had no priest, half the monks and nuns had left Prussia, a third of the monasteries and convents were closed, 1800 parish priests were imprisoned or exiled, and thousands of laypeople were imprisoned for helping the priests.[20]

The Kulturkampf backfired, as it energized the Catholics to become a political force in the Centre party and revitalized Polish resistance. The Kulturkampf ended about 1880 with a new pope Leo XIII willing to negotiate with Bismarck. Bismarck broke with the Liberals over religion and over their opposition to tariffs; He won Centre party support on most of his conservative policy positions, especially his attacks against Socialism.

Italy

Anti-clericalism in Italy is connected with reaction against the absolutism of the Papal States, overthrown in 1870. For a long time, the Pope required Catholics not to participate in the public life of the Kingdom of Italy that had invaded the Papal States to complete the unification of Italy, prompting the pope to declare himself a "prisoner" in the Vatican. Some politicians that had played important roles in this process, such as Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour, were known to be hostile to the temporal and political power of the Church. Throughout the history of Liberal Italy, relations between the Italian government and the Church remained acrimonious, and anticlericals maintained a prominent position in the ideological and political debates of the era. Tensions eased between church and state in the 1890s and early 1900s as a result of both sides' mutual hostility toward the burgeoning Socialist movement, but official hostility between the Holy See and the Italian state was finally settled by fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and Pope Pius XI: the Lateran Accords were finalised in 1929.

After World War II, anti-clericalism was embodied by the Italian Communist and Italian Socialist parties, in opposition to the Vatican-endorsed party Christian Democracy.

The revision of the Lateran treaties during the 1980s by the Socialist Prime Minister of Italy Bettino Craxi, removed the status of "official religion" of the Catholic Church, but still granted a series of provisions in favour of the Church, such as the eight per thousand law, the teaching of religion in schools, and other privileges.

Recently, the Catholic Church has been taking a more aggressive stance in Italian politics, in particular through Cardinal Camillo Ruini, who often makes his voice heard commenting the political debate and indicating the official line of the Church on various matters. This interventionism has increased with the papacy of Benedict XVI. Anti-clericalism, however, is not the official stance of most parties (with the exception of the Italian Radicals, who, however identify as laicist), as most party leaders consider it an electoral disadvantage to openly contradict the Church: since the demise of the Christian Democracy as a single party, Catholic votes are often swinging between the right and the left wing, and are considered to be decisive to win an election.

Poland

Palikot's Movement, is an anti-clerical party founded in 2011 by politician Janusz Palikot. Palikot's Movement won 10% of the national vote at the Polish parliamentary election, 2011. This was an unprecedented result for an anti-church party in Poland, where Catholicism is believed to be deeply rooted.[citation needed]

Portugal

A first wave of anti-clericalism occurred in 1834 when under the government of Dom Pedro all convents and monasteries in Portugal were abolished, simultaneously closing some of Portugal's primary educational establishments.

The fall of the Monarchy in the Republican revolution of 1910 led to another wave of anti-clerical activity. Most church property was put under State control, and the church was not allowed to inherit property. The revolution and the republic which took a "hostile" approach to the issue of church and state separation, like that of the French Revolution, the Spanish Constitution of 1931 and the Mexican Constitution of 1917.[21] As part of the anticlerical revolution, the bishops were driven from their dioceses, the property of clerics was seized by the state, wearing of the cassock was banned, all minor seminaries were closed and all but five major seminaries.[22] A law of February 22, 1918 permitted only two seminaries in the country, but they had not been given their property back.[22] Religious orders were expelled from the country, including 31 orders comprising members in 164 houses (in 1917 some orders were permitted to form again).[22] Religious education was prohibited in both primary and secondary school.[22] Religious oaths and church taxes were also abolished.

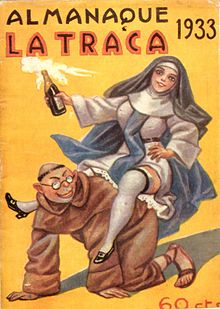

Spain

The first instance of anti-clerical violence due to political conflict in 19th century Spain occurred during the Trienio Liberal (Spanish Civil War of 1820–1823). During riots in Catalonia, 20 clergymen were killed by members of the liberal movement in retaliation for the Church's siding with absolutist supporters of Ferdinand VII.

In 1836 following the First Carlist War, the Ecclesiastical Confiscations of Mendizábal (Template:Lang-es) promulgated by Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, prime minister of the new regime abolished the major Spanish Convents and Monasteries.[23]

Many years later the Radical Republican Party leader Alejandro Lerroux would distinguish himself by his inflammatory pieces of opinion.

Second Republic and Civil War (1931-1939)

The Republican government which came to power in Spain in 1931 was based on secular principles. In the first years some laws were passed secularising education, prohibiting religious education in the schools, and expelling the Jesuits from the country. On Pentecost 1932, Pope Pius XI protested against these measures and demanded restitution. He asked the Catholics of Spain to fight with all legal means against the injustices. June 3, 1933 he issued the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis, in which he described the expropriation of all Church buildings, episcopal residences, parish houses, seminaries and monasteries.

By law, they were now property of the Spanish State, to which the Church had to pay rent and taxes in order to continuously use these properties. "Thus the Catholic Church is compelled to pay taxes on what was violently taken from her"[24] Religious vestments, liturgical instruments, statues, pictures, vases, gems and other valuable objects were expropriated as well.[25]

The Civil War in Spain started in 1936, during which thousands of churches were destroyed, thirteen bishops and some 7,000 clergy and religious Spaniards were assassinated.[26] Catholics largely supported Franco and the Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939.

Anti-clerical assaults during what has been termed by the Nationalists Red Terror included sacking and burning monasteries and churches and killing 6,832 priests,[27] including 13 bishops, 4,184 diocesan priests, 2,365 members of male religious orders, among them 259 Claretians, 226 Franciscans, 204 Piarists, 176 Brothers of Mary, 165 Christian Brothers, 155 Augustinians, 132 Dominicans, and 114 Jesuits.

13 bishops were killed from the dioceses of Sigüenza, Lleida, Cuenca, Barbastro Segorbe, Jaén, Ciudad Real, Almería, Guadix, Barcelona, Teruel and the auxiliary of Tarragona.[28] Aware of the dangers, they all decided to remain in their cities. I cannot go, only here is my responsibility, whatever may happen, said the Bishop of Cuenca[28] In addition 4,172 diocesan priests, 2,364 monks and friars, among them 259 Clarentians, 226 Franciscans, 204 Piarists, 176 Brothers of Mary, 165 Christian Brothers, 155 Augustinians, 132 Dominicans, and 114 Jesuits were killed.[29] In some dioceses, a number of secular priests were killed:

- In Barbastro 123 of 140 priests were killed.[28] about 88 percent of the secular clergy were murdered, 66 percent

- In Lleida, 270 of 410 priests were killed.[28] about 62 percent

- In Tortosa, 44 percent of the secular priests were killed.[27]

- In Toledo 286 of 600 priests were killed.[28]

- In the dioceses of Málaga, Minorca and Segorbe, about half of the priests were killed"[27][28]

- In Madrid 4,000 priests were murdered.

One source records that 283 nuns were killed, some of whom were badly tortured.[28] There are accounts of Catholic faithful being forced to swallow rosary beads, thrown down mine shafts and priests being forced to dig their own graves before being buried alive.[29][30] The Catholic Church has canonized several martyrs of the Spanish Civil War and beatified hundreds more.

Canada

In French Canada following the Conquest, much like in Ireland or Poland under foreign rule, the Catholic Church was the sole national institution not under the direct control of the British colonial government. It was also a major marker of social difference from the incoming Anglo-Protestant settlers. French Canadian identity was almost entirely centred around Catholicism, and to a much lesser extent the French language. However, there was a small anti-clerical movement in French Canada in the early nineteenth drawing inspiration from American and French liberal revolutions. This group was one current (but by no means the dominant) one in the Parti canadien its associated Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837. In the more democratic politics that followed the rebellions, the more radical and anti-clerical tendency eventually formed the Parti rouge in 1848.

At the same time in English Canada, a related phenomenon occurred where the primarily Nonconformist (mostly Presbyterian and Methodist) Reform movement conflicted with an Anglican establishment. In Upper Canada, The Reform Movement began as protest against the "establishment" of the Anglican church.[31]

The vastly different religious backgrounds of the Reformers and rouges was one of the factors which prevented them from working together well during the era of two-party coalition government in Canada (1840–1867). By 1861, however, the two group fused to create the a united Liberal block.[32] After 1867, this party added like-minded reformers from the Maritime provinces, but struggled to win power, especially in still strongly-Catholic Quebec.

Once Wilfrid Laurier became party leader, however, the party dropped its anti-clerical stance and went on to dominate Canadian politics throughout most of the twentieth century. Since that time, Liberal prime ministers have been overwhelmingly Catholic (St. Laurent, Trudeau, Chrétien, Martin), but since the 1960s Liberals have again had a strained relationship with the Catholic church, and have increasing parted with the Catholic church's teachings on sexual morality, as when Trudeau legalized homosexuality and streamlined divorce (as justice minister under Pearson), and Martin legalized same-sex marriage.

In Quebec itself, the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s broke the hold of the church on provincial politics. The Quebec Liberal Party embraced formerly taboo social democratic ideas, and the state intervened in fields once dominated by the church, especially health and education, which were taken over by the provincial government. Quebec is now considered[by whom?] Canada's most secular province.

United States

Although anti-clericalism is more often spoken of regarding the history or current politics of Latin countries where the Catholic Church was established and where the clergy had privileges, Philip Jenkins notes in his 2003 book The New Anti-Catholicism that the U.S., despite the lack of Catholic establishments, has always had anti-clericals.[33]

Latin America

Of the population of Latin America, about 71% acknowledge allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church.[34][35] Consequently, about 43% of the world's Catholics inhabit the ‘Latin’ countries of South, Central and North America.[35]

The slowness to embrace religious freedom in Latin America is related to its colonial heritage and to its post-colonial history. The Aztec, Maya and Inca cultures made substantial use of religious leaders to ideologically support governing authority and power. This pre-existing role of religion as ideological adjunct to the state in pre-Columbian culture made it relatively easy for the Spanish conquistadors to replace native religious structures with those of a Catholicism that was closely linked to the Spanish throne.[36]

Anti-clericalism was a common feature of 19th-century liberalism in Latin America. This anti-clericalism was often purportedly based on the idea that the clergy (especially the prelates who ran the administrative offices of the Church) were hindering social progress in areas such as public education and economic development.

Beginning in the 1820s, a succession of liberal regimes came to power in Latin America.[37] Some members of these liberal regimes sought to imitate the Spain of the 1830s (and revolutionary France of a half-century earlier) in expropriating the wealth of the Catholic Church, and in imitating the eighteenth-century benevolent despots in restricting or prohibiting the religious orders. As a result, a number of these liberal regimes expropriated Church property and tried to bring education, marriage and burial under secular authority. The confiscation of Church properties and changes in the scope of religious liberties (in general, increasing the rights of non-Catholics and non-observant Catholics, while licensing or prohibiting the orders) generally accompanied secularist, and later, Marxist-leaning, governmental reforms.[38]

Mexico

The Mexican Constitution of 1824 had required the Republic to prohibit the exercise of any religion other than the Roman Catholic and Apostolic faith.[39]

Reform War

Starting in 1855, President Benito Juárez issued decrees nationalizing church property, separating church and state, and suppressing religious orders. Church properties were confiscated and basic civil and political rights were denied to religious orders and the clergy.

Cristero War

More severe laws called Calles Law during the rule of Plutarco Elías Calles eventually led to the Cristero War, an armed peasant rebellion against the Mexican government supported by the Catholic Church.[40]

Following the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the new Mexican Constitution of 1917 contained further anti-clerical provisions. Article 3 called for secular education in the schools and prohibited the Church from engaging in primary education; Article 5 outlawed monastic orders; Article 24 forbade public worship outside the confines of churches; and Article 27 placed restrictions on the right of religious organizations to hold property. Most offensively to Catholics,[citation needed] Article 130 deprived clergy members of basic political rights. Many of these laws were resisted, leading to the Cristero Rebellion of 1927–1929. The suppression of the Church included the closing of many churches and the killing of priests. The persecution was most severe in Tabasco under the atheist"[41] governor Tomás Garrido Canabal.

The church-supported armed rebellion only escalated the violence. US Diplomat Dwight Morrow was brought in to mediate the conflict. But 1928 saw the assassination of President Alvaro Obregón by Catholic radical José de León Toral, gravely damaging the peace process.

The war had a profound effect on the Church. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed.[42] Between 1926 and 1934, over 3,000 priests were exiled or assassinated.[43][44]

Where 4,500 priests served the people before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination.[42][45] It appears that ten states were left without any priests.[45]

The Cristero rebels committed their share of violence, which continued even after formal hostilities had ended. In some of the worst cases, public school teachers were tortured and murdered by the former Cristero rebels.[46][47][48] It is calculated that almost 300 rural teachers were murdered in this way between 1935 and 1939,[49]

Ecuador

This issue was one of the bases for the lasting dispute between Conservatives, who represented primarily the interests of the Sierra and the church, and the Liberals, who represented those of the Costa and anticlericalism. Tensions came to a head in 1875 when the conservative President Gabriel García Moreno, after being elected to his third term, was allegedly assassinated by anticlerical Freemasons.[50][51]

Colombia

Colombia enacted anticlerical legislation and its enforcement during more than three decades (1849–84).

La Violencia refers to an era of civil conflict in various areas of the Colombian countryside between supporters of the Colombian Liberal Party and the Colombian Conservative Party, a conflict which took place roughly from 1948 to 1958.[52][53]

Across the country, militants attacked churches, convents, and monasteries, killing priests and looking for arms, since the conspiracy theory maintained that the religious had guns, and this despite the fact that not a single serviceable weapon was located in the raids.[54]

When their party came to power in 1930, anticlerical Liberals pushed for legislation to end Church influence in public schools. These Liberals held that the Church and its intellectual backwardness were responsible for a lack of spiritual and material progress in Colombia. Liberal-controlled local, departmental and national governments ended contracts with religious communities who operated schools in government-owned buildings, and set up secular schools in their place. These actions were sometimes violent, and were met by a strong opposition from clerics, Conservatives, and even a good number of more moderate Liberals.

Argentina

The original Argentine Constitution of 1853 provided that all Argentine presidents must be Catholic and stated that the duty of the Argentine congress was to convert the Indians to Catholicism. All of these provisions have been eliminated with the exception of the mandate to "sustain" Catholicism.

Liberal anti-clericalists of the 1880s established a new pattern of church-state relations in which the official constitutional status of the Church was preserved while the state assumed control of many functions formerly the province of the Church. Conservative Catholics, asserting their role as definers of national values and morality, responded in part by joining in the rightist religio-political movement known as Catholic Nationalism which formed successive opposition parties. This began a prolonged period of conflict between church and state that persisted until the 1940s when the Church enjoyed a restoration of its former status under the presidency of Colonel Juan Perón. Perón claimed that Peronism was the "true embodiment of Catholic social teaching" – indeed, more the embodiment of Catholicism than the Catholic Church itself.

In 1954, Argentina saw extensive destruction of churches, denunciations of clergy and confiscation of Catholic schools as Perón attempted to extend state control over national institutions.[55]

The renewed rupture in church-state relations was completed when Perón was excommunicated. However, in 1955, he was overthrown by a military general who was a leading member of the Catholic Nationalist movement.

Venezuela

In Venezuela, the government of Antonio Guzmán Blanco (in office from 1870–1877, from 1879–1884, and from 1886–1887) virtually crushed the institutional life of the church, even attempting to legalize the marriage of priests. These anticlerical policies remained in force for decades afterward.

Cuba

Cuba, under the rule of atheist Fidel Castro, succeeded in reducing the Church's ability to work by deporting the archbishop and 150 Spanish priests, by discriminating against Catholics in public life and education and by refusing to accept them as members of the Communist Party.[56] The subsequent flight of 300,000 people from the island also helped to diminish the Church there.[56]

Communism

Most Marxist–Leninist governments have been officially anti-clerical, abolishing religious holidays, teaching atheism in schools, closing monasteries, church social and educational institutions and many churches.[57] In the Soviet Union, anti-clericalism was expressed through the state; in the first five years alone after the Bolshevik revolution, 28 bishops and 1,200 priests were executed.[58]

Anticlericalism in the Islamic world

Indonesia

During the fall of Suharto in 1998, a witch hunt in Banyuwangi against alleged sorcerers spiraled into widespread riots and violence. In addition to alleged sorcerers, Islamic clerics were also targeted and killed, Nahdlatul Ulama members were murdered by rioters.[59][60]

Iran

In 1925, Rezā Khan founded the Imperial State of Iran and proclaimed himself shah of the country. As part of his Westernization program, the traditional role of the ruling clergy was minimized; Islamic schools were secularized, women were forbidden to wear the hijab, sharia law was abolished, and men and women were desegregated in educational and religious environments. All this infuriated the ultraconservative clergy as a class. Rezā Khan's son and heir Mohammad Reza Pahlavi continued such practices. They ultimately contributed to the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79, and the Shah's flight from his country.

When Ayatollah Khomeini took power a month after the revolution, the Shah's anticlerical measures were largely overturned, replaced by an Islamic Republic based on the principle of rule by Islamic jurists, velayat-e faqih, where clerics serve as head of state and in many powerful governmental roles. However, by the late 1990s and 2000s anti-clericalism was reported to be significant in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

"Iran, although an Islamic state, imbued with religion and religious symbolism, is an increasingly anti-clerical country. In a sense it resembles some Roman Catholic countries where religion is taken for granted, without public display, and with ambiguous feelings towards the clergy. Iranians tend to mock their mullahs, making mild jokes about them ..."[61]

Demonstrators using slogans such as "The clerics live like kings while we live in poverty!" One report claims "Working-class Iranian lamented clerical wealth in the face of their own poverty," and "stories about Swiss bank accounts of leading clerics circulated on Tehran's rumor mill."[62]

Certain branches of Freemasonry

According to the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia, Freemasonry was historically viewed by the Catholic Church as a principal source of anti-Clericalism,[63] – especially in, but not limited to,[64] historically Catholic countries.

See also

- Age of Enlightenment

- Agnosticism

- Clericalism

- Cristero War

- Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution

- Denis Diderot

- Dissolution of the Monasteries

- Freethought

- Kulturkampf, anti-Catholicism in Prussia in the 1870s.

- Laïcité

- La Violencia

- Red Terror (Spain)

- Reign of Terror

- Relations between the Catholic Church and the state

- Secularism

- Secular state

- Separation of church and state

- Theocracy

- Thomas Paine

- Voltaire

Notes

- ^ José Mariano Sánchez, Anticlericalism: a brief history (University of Notre Dame Press, 1972)

- ^ Collins, Michael (1999). The Story of Christianity. Mathew A Price. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7513-0467-1. [page needed]

- ^ a b Helmstadter, Richard J. (1997). Freedom and religion in the nineteenth century. Stanford Univ. Press. p. 251.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c Duffy, Eamon (1997). Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes. Yale University Press in association with S4C. Library of Congress Catalog card number 97-60897.

- ^ Napoleon's Legacy: Problems of Government in Restoration Europe - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The Churchman - Google Books. Books.google.com. 1985-12-29. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Prosperity and Plunder: European Catholic Monasteries in the Age of ... - Derek Edward Dawson Beales - Google Books. Books.google.com. 2003-07-24. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Notes On Monastero San Paolo: Reentering The Vestibule of Paradise - Gordon College". Gordon.edu. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Historique I". St-benoit-du-lac.com. 1941-07-11. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ A History of the Popes: 1830 - 1914 - Owen Chadwick - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Alston, Cyprian (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Wootton and Fishbourne Archived September 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "RGM 2005 OCSO". Citeaux.net. 1947-02-28. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Franklin 2006, p. 9 (footnote 26) cites Larkin, Maurice. Church and State after the Dreyfus Affair. pp. 138–41.: "Freemasonry in France". Austral Light. 6: 164–72, 241–50. 1905.

- ^ Franz, H. (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Okey 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Berenger 1990, p. 102.

- ^ "In Germany and Austria, Freemasonry during the eighteenth century was a powerful ally of the so-called party, of "Enlightenment" (Aufklaerung), and of Josephinism" (Gruber 1909) .

- ^ Michael B. Gross, The war against Catholicism: liberalism and the anti-Catholic imagination in nineteenth-century Germany, p. 1, University of Michigan Press, 2004

- ^ Richard J. Helmstadter, Freedom and religion in the nineteenth century (1997), p. 19

- ^

Maier, Hans (2004). Totalitarianism and Political Religions. trans. Jodi Bruhn. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 0-7146-8529-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d Jedin, Dolan & Adriányi 1981, p. 612.

- ^ Germán Rueda Hernánz, La desamortización en España: un balance, 1766-1924, Arco Libros. 1997. ISBN 978-84-7635-270-0

- ^ Dilectissima Nobis 1933, § 9–10

- ^ Dilectissima Nobis 1933, § 12

- ^ Franzen & Bäumer 1988, p. 397.

- ^ a b c de la Cueva 1998, p. 355

- ^ a b c d e f g Jedin, Repgen & Dolan 1999, p. 617.

- ^ a b Beevor 2006, p. [page needed].

- ^ Thomas 1961, p. 174.

- ^ Wilton, Carol (2000). Popular Politics and Political Culture in Upper Canada 1800-1850. Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press. pp. 51–53.

- ^ "Federal Parties: The Liberal Party of Canada". Canadian-Politics.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-10. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jenkins, Philip, The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice, p. 10, Oxford University Press US, 2004

- ^ Fraser, Barbara J., In Latin America, Catholics down, church's credibility up, poll says[permanent dead link] Catholic News Service June 23, 2005

- ^ a b Oppenheimer, Andres Fewer Catholics in Latin America San Diego Tribune May 15, 2005

- ^ Sigmund, Paul E. (1996). "Religious Human Rights in the World Today: A Report on the 1994 Atlanta Conference: Legal Perspectives on Religious Human Rights: Religious Human Rights in Latin America". Emory International Law Review. Emory University School of Law.

- ^ Stacy, Mexico and the United States (2003), p. 139

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 167–72

- ^ "Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States (1824)". Tarlton.law.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chadwick, A History of Christianity (1995), pp. 264–5

- ^ Peter Godman, "Graham Greene's Vatican Dossier" The Atlantic Monthly 288.1 (July/August 2001): 85.

- ^ a b Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo (2003), p. 33

- ^ Van Hove, Brian (1994). "Blood Drenched Altars". EWTN. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ a b Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 p. 33 (2003 Brassey's) ISBN 978-1-57488-452-4

- ^ John W. Sherman (1997). The Mexican right: the end of revolutionary reform, 1929–1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0-275-95736-0.

- ^ Marjorie Becker (1995). Setting the Virgin on fire: Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán peasants, and the redemption of the Mexican Revolution. University of California Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-520-08419-3.

- ^ Cora Govers (2006). Performing the community: representation, ritual and reciprocity in the Totonac Highlands of Mexico. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-8258-9751-2.

- ^ Nathaniel Weyl, Mrs. Sylvia Castleton Weyl (1939). The reconquest of Mexico: the years of Lázaro Cárdenas. Oxford university press. p. 322.

- ^ Berthe, P. Augustine, translated from French by Mary Elizabeth Herbert Garcia Moreno, President of Ecuador, 1821–1875 p. 297-300, 1889 Burns and Oates

- ^ Burke, Edmund Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad, for the year 1875 p.323 1876 Rivingtons

- ^ Stokes, Doug (2005). America's Other War : Terrorizing Colombia. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-547-9. p. 68, Both Livingstone and Stokes quote a figure of 200,000 dead between 1948–1953 (Livingstone) and "a decade war" (Stokes)

*Azcarate, Camilo A. (March 1999). "Psychosocial Dynamics of the Armed Conflict in Colombia". Online Journal of Peace and Conflict Resolution. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Azcarate quotes a figure of 300,000 dead between 1948–1959

*Gutiérrez, Pedro Ruz (October 31, 1999). "Bullets, Bloodshed And Ballots;For Generations, Violence Has Defined Colombia's Turbulent Political History". Orlando Sentinel (Florida): G1.Political violence is not new to that South American nation of 38 million people. In the past 100 years, more than 500,000 Colombians have died in it. From the "War of the Thousand Days," a civil war at the turn of the century that left 100,000 dead, to a partisan clash between 1948 and 1966 that claimed nearly 300,000... - ^ Bergquist, Charles; David J. Robinson (1997–2005). "Colombia". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2005. Microsoft Corporation. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved April 16, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)On April 9, 1948, Gaitán was assassinated outside his law offices in downtown Bogotá. The assassination marked the start of a decade of bloodshed, called La Violencia (the violence), which took the lives of an estimated 180,000 Colombians before it subsided in 1958. - ^ Williford 2005, p. 218.

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 167–8

- ^ a b Chadwick, A History of Christianity (1995), p. 266

- ^ 2008 Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom

- ^ Ostling, Richard (June 24, 2001). "Cross meets Kremlin". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.insideindonesia.org/weekly-articles/the-banyuwangi-murders

- ^ http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2053925,00.html

- ^ Economist staff 2000.

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p.163

- ^ "From the official documents of French Masonry contained principally in the official 'Bulletin' and 'Compte-rendu' of the Grand Orient it has been proved that all the anti-clerical measures passed in the French Parliament were decreed beforehand in the Masonic lodges and executed under the direction of the Grand Orient, whose avowed aim is to control everything and everybody in France" (Gruber 1909 cites "Que personne ne bougera plus en France en dehors de nous", "Bull. Gr. Or.", 1890, 500 sq.)

- ^ "But in spite of the failure of the official transactions, there are a great many German and not a few American Masons, who evidently favour at least the chief anti-clerical aims of the Grand Orient party" (Gruber 1909)

References

- Beevor, Antony (2006), The Battle For Spain; The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

- Berenger, Jean (1990), A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1700-1918, Edinburgh: Addison Wesley

- de la Cueva, Julio (1998), "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War", Journal of Contemporary History, XXXIII (3), JSTOR 261121

- Economist staff (February 17, 2000), "The people against the mullahs", The Economist

- Franklin, James (2006), "Freemasonry in Europe", Catholic Values and Australian Realities, Connor Court Publishing Pty Ltd, pp. 7–10, ISBN 9780975801543

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Gross, Michael B. The war against Catholicism: Liberalism and the anti-Catholic imagination in nineteenth-century Germany (University of Michigan Press, 2004)

- Gruber, Hermann (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jedin, Hubert; Dolan, John; Adriányi, Gabriel (1981), History of the Church: The Church in the Twentieth Century, vol. X, Continuum International Publishing Group

- Jedin, Hubert; Repgen, Konrad; Dolan, John, eds. (1999) [1981], History of the Church: The Church in the Twentieth Century, vol. X, New York & London: Burn & Oates

- Okey, Robin (2002), The Habsburg Monarchy c. 1765-1918, New York: Palgrave MacMillan

- Sánchez, José Mariano. Anticlericalism: a brief history (University of Notre Dame Press, 1972)

- Thomas, Hugh (1961), The Spanish Civil War, ???: Touchstone, ISBN 0-671-75876-4.

- Williford, Thomas J. (2005), Armando los espiritus: Political Rhetoric in Colombia on the Eve of La Violencia, 1930–1945, Vanderbilt University