Astrobiology

Astrobiology (other terms have been exobiology, exopaleontology, and bioastronomy) is the study of the origin, evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. This interdisciplinary field encompasses the search for habitable environments in our Solar System and habitable planets outside our Solar System, the search for evidence of prebiotic chemistry, life on Mars and other bodies in our Solar System, laboratory and field research into the origins and early evolution of life on Earth, and studies of the potential for life to adapt to challenges on Earth and in outer space.[2]

Astrobiology makes use of physics, chemistry, astronomy, biology, molecular biology, ecology, planetary science, geography and geology to investigate the possibility of life on other worlds and help recognize biospheres that might be quite different from the Earth's.[3][4] However, astrobiology concerns itself with an interpretation of existing scientific data; given more detailed and reliable data from other parts of the Universe, the roots of astrobiology itself —biology, physics, chemistry— may have their theoretical bases challenged. Much speculation is entertained in the field to give context, and astrobiology concerns itself primarily with hypotheses that fit firmly into existing scientific theories.

Overview

The etymology of astrobiology comes from Greek ἄστρον, astron, "constellation, star"; βίος, bios, "life"; and -λογία, -logia, study. Although astrobiology is an emerging field and still a developing subject, the question of whether life exists elsewhere in the universe is a verifiable hypothesis and thus a valid line of scientific inquiry. David Grinspoon, a planetary scientist, calls astrobiology a field of natural philosophy, grounding speculation on the unknown, in known scientific theory.[6][7] Though once considered outside the mainstream of scientific inquiry, astrobiology has become a formalized field of study. NASA funded its first astrobiology project in 1959 and established an astrobiology program in 1960.[2][8] NASA’s Viking missions to Mars, launched in 1976, included three biology experiments designed to look for possible signs of life. In 1971, NASA funded the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) to survey the sky to detect the existence of transmissions from a civilization on a distant planet. The Mars Pathfinder lander in 1997 carried a scientific payload intended for exopaleontology in the hopes of finding microbial fossils entombed in the rocks.[9]

In the 21st century, astrobiology is a focus of a growing number of NASA and European Space Agency Solar System exploration missions. The first European workshop on astrobiology took place in May 2001 in Italy,[10] and the outcome was the Aurora programme.[11] Currently, NASA hosts the NASA Astrobiology Institute and a growing number of universities in the United States (e.g., University of Arizona, Penn State University, and University of Washington), Britain (e.g., The University of Glamorgan[12]), Canada, Ireland, and Australia (e.g., The University of New South Wales[13]) now offer graduate degree programs in astrobiology.

A particular focus of current astrobiology research is the search for life on Mars due to its proximity to Earth and geological history. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that Mars has previously had a considerable amount of water on its surface, water being considered to be an essential precursor to the development of carbon-based life.[14]

Missions specifically designed to search for life include the Viking program and Beagle 2 probes, both directed to Mars. The Viking results were inconclusive,[15] and Beagle 2 failed to transmit from the surface and is assumed to have crashed.[16] A future mission with a strong astrobiology role would have been the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, designed to study the frozen moons of Jupiter—some of which may have liquid water—had it not been cancelled. Recently, the Phoenix lander probed the environment for past and present planetary habitability of microbial life on Mars, and to research the history of water there.

In 2011, NASA plans to launch the Mars Science Laboratory rover which will continue the search for past or present life on Mars using a variety of scientific instruments. The European Space Agency has been developing the ExoMars astrobiology rover, which is to be launched on 2018.

The International Astronomical Union regularly organizes major international conferences through its Commission 51: Bioastronomy. Commission 51 - Bioastronomy: Search for Extraterrestrial Life was established by the IAU in 1982 and is now hosted by the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Hawai'i.

Methodology

Narrowing the task

When looking for life on other planets, some simplifying assumptions are useful to reduce the size of the task of astrobiologist. One is to assume that the vast majority of life forms in our galaxy are based on carbon chemistries, as are all life forms on Earth.[17] While it is possible that non-carbon-based life exists, carbon is well known for the unusually wide variety of molecules that can be formed around it.

The presence of liquid water is a useful assumption, as it is a common molecule and provides an excellent environment for the formation of complicated carbon-based molecules that could eventually lead to the emergence of life.[18] Some researchers posit environments of ammonia, or more likely water-ammonia mixtures.[19] These environments are considered suitable for carbon or noncarbon-based life, while opening more temperature ranges (and thus worlds) for life.

A third assumption is to focus on sun-like stars. This comes from the idea of planetary habitability.[20] Very big stars have relatively short lifetimes, meaning that life would not likely have time to evolve on planets orbiting them. Very small stars provide so little heat and warmth that only planets in very close orbits around them would not be frozen solid, and in such close orbits these planets would be tidally "locked" to the star.[21] Without a thick atmosphere, one side of the planet would be perpetually baked and the other perpetually frozen. In 2005, the question was brought back to the attention of the scientific community, as the long lifetimes of red dwarfs could allow some biology on planets with thick atmospheres. This is significant, as red dwarfs are extremely common. (See Habitability of red dwarf systems).

It is estimated that 10% of the stars in our galaxy are sun-like; There are about a thousand such stars within 100 light-years of our Sun. These stars would be useful primary targets for interstellar listening. Since Earth is the only planet known to harbor life, there is no evident way to know if any of the simplifying assumptions are correct.

Elements of astrobiology

Astronomy

Most astronomy-related astrobiological research falls into the category of extrasolar planet (exoplanet) detection, the hypothesis being that if life arose on Earth, then it could also arise on other planets with similar characteristics. To that end, a number of instruments designed to detect Earth-like exoplanets are under development, most notably NASA's Terrestrial Planet Finder (TPF) and ESA's Darwin programs. Additionally, NASA has launched the Kepler mission in March 2009, and the French Space Agency has launched the COROT space mission in 2006.[22][23] There are also several less ambitious ground-based efforts underway. (See exoplanet).

The goal of these missions is not only to detect Earth-sized planets, but also to directly detect light from the planet so that it may be studied spectroscopically. By examining planetary spectra, it would be possible to determine the basic composition of an extrasolar planet's atmosphere and/or surface; given this knowledge, it may be possible to assess the likelihood of life being found on that planet. A NASA research group, the Virtual Planet Laboratory,[24] is using computer modeling to generate a wide variety of virtual planets to see what they would look like if viewed by TPF or Darwin. It is hoped that once these missions come online, their spectra can be cross-checked with these virtual planetary spectra for features that might indicate the presence of life. The photometry temporal variability of extrasolar planets may also provide clues to their surface and atmospheric properties.

An estimate for the number of planets with intelligent extraterrestrial life can be gleaned from the Drake equation, essentially an equation expressing the probability of intelligent life as the product of factors such as the fraction of planets that might be habitable and the fraction of planets on which life might arise:[25]:

where, N = The number of communicative civilizations, R* = The rate of formation of suitable stars (stars such as our Sun), fp = The fraction of those stars with planets. (Current evidence indicates that planetary systems may be common for stars like the Sun), ne = The number of Earth-like worlds per planetary system, fl = The fraction of those Earth-like planets where life actually develops, fi = The fraction of life sites where intelligence develops, fc = The fraction of communicative planets (those on which electromagnetic communications technology develops), L = The "lifetime" of communicating civilizations.

However, whilst the rationale behind the equation is sound, it is unlikely that the equation will be constrained to reasonable error limits any time soon. The first term, Number of Stars, is generally constrained within a few orders of magnitude. The second and third terms, Stars with Planets and Planets with Habitable Conditions, are being evaluated for the sun's neighborhood. Another associated topic is the Fermi paradox, which suggests that if intelligent life is common in the Universe, then there should be obvious signs of it. This is the purpose of projects like SETI, which tries to detect signs of radio transmissions from intelligent extraterrestrial civilizations.

Another active research area in astrobiology is Planetary system formation. It has been suggested that the peculiarities of our Solar System (for example, the presence of Jupiter as a protective shield[26]) may have greatly increased the probability of intelligent life arising on our planet.[27][28] No firm conclusions have been reached so far.

Biology

Extremophiles (organisms able to survive in extreme environments) are a core research element for astrobiologists. Such organisms include biota able to survive kilometers below the ocean's surface near hydrothermal vents and microbes that thrive in highly acidic environments.[29]

Until the 1970s, life was believed to be entirely dependent on energy from the Sun. Plants on Earth's surface capture energy from sunlight to photosynthesize sugars from carbon dioxide and water, releasing oxygen in the process, and are then eaten by oxygen-respiring animals, passing their energy up the food chain. Even life in the ocean depths, where sunlight cannot reach, was believed to obtain its nourishment either from consuming organic detritus rained down from the surface waters or from eating animals that did.[30] A world's ability to support life was thought to depend on its access to sunlight. However, in 1977, during an exploratory dive to the Galapagos Rift in the deep-sea exploration submersible Alvin, scientists discovered colonies of giant tube worms, clams, crustaceans, mussels, and other assorted creatures clustered around undersea volcanic features known as black smokers.[30] These creatures thrive despite having no access to sunlight, and it was soon discovered that they comprise an entirely independent food chain. Instead of plants, the basis for this food chain is a form of bacterium that derives its energy from oxidization of reactive chemicals, such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, that bubble up from the Earth's interior. This chemosynthesis revolutionized the study of biology by revealing that life need not be sun-dependent; it only requires water and an energy gradient in order to exist. It is now known that extremophiles thrive in ice, boiling water, acid, the water core of nuclear reactors, salt crystals, toxic waste and in a range of other extreme habitats that were previously thought to be inhospitable for life.[31] It opened up a new avenue in astrobiology by massively expanding the number of possible extraterrestrial habitats. Characterization of these organisms—their environments and their evolutionary pathways—is considered a crucial component to understanding how life might evolve elsewhere in the Universe. Some organisms able to withstand exposure to the vacuum and radiation of space include the lichen fungi Rhizocarpon geographicum and Xanthoria elegans,[32] the bacterium Bacillus safensis,[33] Deinococcus radiodurans,[33] Bacillus subtilis,[33] yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae,[33] seeds from Arabidopsis thaliana ('mouse-ear cress'),[33] as well as the invertebrate animal Tardigrade.[33]

The origin of life, distinct from the evolution of life, is another ongoing field of research. Oparin and Haldane postulated that the conditions on the early Earth were conducive to the formation of organic compounds from inorganic elements and thus to the formation of many of the chemicals common to all forms of life we see today. The study of this process, known as prebiotic chemistry, has made some progress, but it is still unclear whether or not life could have formed in such a manner on Earth. The alternative theory of panspermia is that the first elements of life may have formed on another planet with even more favorable conditions (or even in interstellar space, asteroids, etc.) and then have been carried over to Earth by a variety of means. See Origin of life. Jupiter's moon, Europa, is now considered to be the most likely location for extant extraterrestrial life in the Solar System.[31][34][35][36][37][38]

Astrogeology

Astrogeology is a planetary science discipline concerned with the geology of the celestial bodies such as the planets and their moons, asteroids, comets, and meteorites. The information gathered by this discipline allows the measure of a planet's or a natural satellite's potential to develop and sustain life, or planetary habitability.

An additional discipline of astrogeology is geochemistry, which involves study of the chemical composition of the Earth and other planets, chemical processes and reactions that govern the composition of rocks and soils, the cycles of matter and energy and their interaction with the hydrosphere and the atmosphere of the planet. Specializations include cosmochemistry, biochemistry and organic geochemistry.

The fossil record provides the oldest known evidence for life on Earth.[39] By examining this evidence, paleontologists are able to understand better the types of organisms that arose on the early Earth. Some regions on Earth, such as the Pilbara in Western Australia and the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica, are also considered to be geological analogs to regions of Mars, and as such, might be able to provide clues on how to search for past life on Mars.

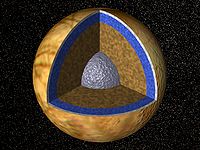

Life in the Solar System

The three most likely candidates for life in the solar system (besides Earth) are the planet Mars, the Jovian moon Europa, and Saturn's moon Titan.[40][41][42][43][44] This speculation is primarily based on the fact that (in the cases of Mars and Europa) the planetary bodies may have liquid water, a molecule essential for life as we know it, for its use as a solvent in cells.[14] Water on Mars is found in its polar ice caps, and newly carved gullies recently observed on Mars suggest that liquid water may exist, at least transiently, on the planet's surface,[45][46] and possibly in subsurface environments such as hydrothermal springs as well. At the Martian low temperatures and low pressure, liquid water is likely to be highly saline.[47] As for Europa, liquid water likely exists beneath the moon's icy outer crust.[35][40][41] This water may be warmed to a liquid state by volcanic vents on the ocean floor (an especially intriguing theory considering the various types of extremophiles that live near Earth's volcanic vents), but the primary source of heat is probably tidal heating.[48]

Another planetary body that could potentially sustain extraterrestrial life is Saturn's largest moon, Titan.[44] Titan has been described as having conditions similar to those of early Earth.[49] On its surface, scientists have discovered the first liquid lakes outside of Earth, but they seem to be composed of ethane and/or methane, not water.[50] After Cassini data was studied, it was reported on March 2008 that Titan may also have an underground ocean composed of liquid water and ammonia.[51] Additionally, Saturn's moon Enceladus may have an ocean below its icy surface.[52]

Criticisms

The systematic search for possible life outside of Earth is a valid multidisciplinary scientific endeavor.[53] The University of Glamorgan, UK, started just such a degree in 2006,[12] and the American government funds the NASA Astrobiology Institute. However, characterization of non-Earth life is unsettled; hypotheses and predictions as to its existence and origin vary widely, but at the present, the development of theories to inform and support the exploratory search for life may be considered astrobiology's most concrete practical application.

Biologist Jack Cohen and mathematician Ian Stewart, amongst others, consider xenobiology separate from astrobiology. Cohen and Stewart stipulate that astrobiology is the search for Earth-like life outside of our solar system and say that xenobiologists are concerned with the possibilities open to us once we consider that life need not be carbon-based or oxygen-breathing, so long as it has the defining characteristics of life. (See carbon chauvinism).

As with all space exploration, there is the classic argument that there is still a lot more scientists have to learn about Earth. Critics[who?] of astrobiology may prefer that public funding remain dedicated towards searching for unknown species in our own terrestrial biosphere. They[who?] feel that Earth is the most plausible and practical region to search for and study life.

Research outcomes

As of 2009, no proof of extraterrestrial life has been identified. Examination of the ALH84001 meteorite, which was recovered in Antarctica in 1984 and believed to have originated from Mars, is thought by some scientists to house microfossils of extraterrestrial origin; this interpretation is controversial.[54][55][56]

- Methane

In 2004, the spectral signature of methane was detected in the Martian atmosphere by both Earth-based telescopes as well as by the Mars Express probe. Because of solar radiation and cosmic radiation, methane is predicted to disappear from the Martian atmosphere within several years, so the gas must be actively replenished in order to maintain the present concentration.[57][58] The Mars Science Laboratory rover will perform precision measurements of oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between a geochemical and a biological origin.[59][60][61]

- Planetary systems

It is possible that some planets, like the gas giant Jupiter in our solar system, may have moons with solid surfaces or liquid oceans that are more hospitable. Most of the planets so far discovered outside our solar system are hot gas giants thought to be inhospitable to life, so it is not yet known whether our solar system, with a warm, rocky, metal-rich inner planet such as Earth, is of an aberrant composition. Improved detection methods and increased observing time will undoubtedly discover more planetary systems, and possibly some more like ours. For example, NASA's Kepler Mission seeks to discover Earth-sized planets around other stars by measuring minute changes in the star's light curve as the planet passes between the star and the spacecraft. Progress in infrared astronomy and submillimeter astronomy has revealed the constituents of other star systems. Infrared searches have detected belts of dust and asteroids around distant stars, underpinning the formation of planets.

- Planetary habitability

Efforts to answer questions such as the abundance of potentially habitable planets in habitable zones and chemical precursors have had much success. Numerous extrasolar planets have been detected using the wobble method and transit method, showing that planets around other stars are more numerous than previously postulated. The first Earth-like extrasolar planet to be discovered within its star's habitable zone is Gliese 581 c, which was found using radial velocity.[62]

Research into the environmental limits of life and the workings of extreme ecosystems is also ongoing, enabling researchers to predict what planetary environments might be most likely to harbor life. Missions such as the Phoenix lander, Mars Science Laboratory, ExoMars to Mars, the Cassini probe to Saturn's moon Titan, and the "Ice Clipper" mission to Jupiter's moon Europa hope to further explore the possibilities of life on other planets in our solar system.

Rare Earth Hypothesis

This hypothesis states that based on astrobiological findings, multi-cellular life forms found on earth may actually be more of a rarity than scientists initially assumed. It provides a possible answer to the Fermi paradox which suggests,"If extraterrestrial aliens are common, why aren't they obvious?" It is apparently in opposition to the principle of mediocrity, assumed by famed astronomers Frank Drake, Carl Sagan, and others. The Principle of Mediocrity suggests that life on Earth is not exceptional, but rather that life is more than likely to be found on innumerable other worlds.

The Anthropic Principle states that fundamental laws of the universe work specifically in a way that life would be possible. The Anthropic Principle supports the Rare Earth Hypothesis by arguing the overall elements that are needed to support life on earth are so fine-tuned that it is nigh impossible for another just like it to exist by random chance (note that these terms are used by scientists in a different way from the vernacular conception of them). However, Stephen Jay Gould compared the claim that the universe is fine-tuned for the benefit of our kind of life to saying that sausages were made long and narrow so that they could fit into modern hot dog buns, or saying that ships had been invented to house barnacles. [63][64]

See also

|

References

- ^ "Launching the Alien Debates (part 1 of 7)". Astrobiology Magazine. NASA. December 08, 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "About Astrobiology". NASA Astrobiology Institute. NASA. January 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ iTWire - Scientists will look for alien life, but Where and How?

- ^ Ward, P. D. (2004). The life and death of planet Earth. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 0805075127.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gutro, Robert (November 4, 2007). "NASA Predicts Non-Green Plants on Other Planets". Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ Elusive Earths | SpaceRef - Your Space Reference

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk (2004). Life in the Universe: Expectations and Constraints. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3540307087.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Living Universe: NASA and the Development of Astrobiology, by Steven J. Dick and James E. Strick, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 2004

- ^ "Exopaleontology at the Pathfinder Landing Site". NASA Ames Research Center. September 5, 1996. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "First European Workshop on Exo/Astrobiology". ESA Press Release. European Space Agency. 2001. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ Science | 1 June 2001 | Vol. 292 | no. 5522 pp. 1626 - 1627 | ESA Embraces Astrobiology | DOI: 10.1126/science.292.5522.1626

- ^ a b CASE Undergraduate Degrees

- ^ The Australian Centre for Astrobiology, University of New South Wales

- ^ a b NOVA | Mars | Life's Little Essential | PBS

- ^ KLEIN, HAROLD P. (1976 - 10 - 01). "The Viking Biological Investigation: Preliminary Results". Science. 194. (4260): 99–105. doi:10.1126/science.194.4260.99. PMID 17793090. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Possible evidence found for Beagle 2 location". European Space Agency. 21 December 2005. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: An Interview With Dr. Farid Salama". Astrobiology magazine. 2000. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ "Astrobiology". Macmillan Science Library: Space Sciences. 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ "The Ammonia-Oxidizing Gene". Astrobiology Magazine. August 19, 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Stars and Habitable Planets". Sol Company. 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ "M Dwarfs: The Search for Life is On". Red Orbit & Astrobiology Magazine. 29 August 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ "Kepler Mission". NASA. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ "The COROT space telescope". CNES. 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ "The Virtual Planet Laboratory". NASA. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ Ford, Steve (1995). "What is the Drake Equation?". SETI League. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Horner, Jonathan (August 24, 2007). "Jupiter: Friend or foe?". Europlanet. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jakosky, Bruce (September 14, 2001). "The Role Of Astrobiology in Solar System Exploration". NASA. SpaceRef.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bortman, Henry (September 29, 2004). "Coming Soon: "Good" Jupiters". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (7 February 2005). "Wild Things: The Most Extreme Creatures". Live Science. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ a b Chamberlin, Sean (1999). "Creatures Of The Abyss: Black Smokers and Giant Worms". Fullerton College. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ a b Cavicchioli, R. (Fall 2002). "Extremophiles and the search for extraterrestrial life". Astrobiology. 2 (3): :281–92. doi:10.1089/153110702762027862. PMID 12530238. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Article: Lichens survive in harsh environment of outer space

- ^ a b c d e f The Planetary Report, Volume XXIX, number 2, March/April 2009, "We make it happen! Who will survive? Ten hardy organisms selected for the LIFE project, by Amir Alexander

- ^ "Jupiter's Moon Europa Suspected Of Fostering Life" (PDF). Daily University Science News. 2002. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ a b Weinstock, Maia (24 August 2000). "Galileo Uncovers Compelling Evidence of Ocean On Jupiter's Moon Europa". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cavicchioli, R. (Fall 2002). "Extremophiles and the search for extraterrestrial life". Astrobiology. 2 (3): :281–92. doi:10.1089/153110702762027862. PMID 12530238. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ David, Leonard (7 February 2006). "Europa Mission: Lost In NASA Budget". Space.com. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Clues to possible life on Europa may lie buried in Antarctic ice". Marshal Space Flight Center. NASA. March 5, 1998. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Fossil SUccession". U.S. Geological Survey. 14 August 1997. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ a b Tritt, Charles S. (2002). "Possibility of Life on Europa". MilwaukeeSchool of Engineering. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ a b Friedman, Louis (December 14, 2005). "Projects: Europa Mission Campaign". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ David, Leonard (10 November 1999). "Move Over Mars -- Europa Needs Equal Billing". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ Than, Ker (28 February 2007). "New Instrument Designed to Sift for Life on Mars". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ a b Than, Ker (13 September 2005). "Scientists Reconsider Habitability of Saturn's Moon". Science.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "NASA Images Suggest Water Still Flows in Brief Spurts on Mars". NASA. 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Water ice in crater at Martian north pole". European Space Agency. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (June 1, 2001). "Martian Water: Are There Extant Halobacteria on Mars?". Astrobiology. 1 (2): 161–164. doi:10.1089/153110701753198927. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Kruszelnicki, Karl (5 November 2001). "Life on Europa, Part 1". ABC Science. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Titan: Life in the Solar System?". BBC - Science & Nature. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Britt, Robert Roy (28 July 2006). "Lakes Found on Saturn's Moon Titan". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lovett, Richard A. (March 20, 2008). "Saturn Moon Titan May Have Underground Ocean". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Saturn moon 'may have an ocean'". BBC News. 2006-03-10. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ NASA Astrobiology Institute

- ^ Crenson, Matt (2006-08-06). "After 10 years, few believe life on Mars". Associated Press (on space.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ McKay, David S., et al. (1996) "Search for Past Life on Mars: Possible Relic Biogenic Activity in Martian Meteorite ALH84001". Science, Vol. 273. no. 5277, pp. 924 - 930. URL accessed March 18, 2006.

- ^ McKay D. S., Gibson E. K., ThomasKeprta K. L., Vali H., Romanek C. S., Clemett S. J., Chillier X. D. F., Maechling C. R., Zare R. N. (1996). "Search for past life on Mars: Possible relic biogenic activity in Martian meteorite ALH84001". Science. 273: 924–930. doi:10.1126/science.273.5277.924. PMID 8688069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Vladimir A. Krasnopolsky (2005). "Some problems related to the origin of methane on Mars". Icarus. 180 (2): 359–367. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.10.015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Planetary Fourier Spectrometer website (ESA, Mars Express)

- ^ "Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite". NASA. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tenenbaum, David (June 09, 2008):). "Making Sense of Mars Methane". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Tarsitano, C.G. and Webster, C.R. (2007). "Multilaser Herriott cell for planetary tunable laser spectrometers". Applied Optics,. 46 (28): 6923–6935. doi:10.1364/AO.46.006923.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Than, Ker (24 April 2007). "Major Discovery: New Planet Could Harbor Water and Life". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Gould, Stephen Jay. "Clear Thinking in the Sciences". Lectures at Harvard University.

{{cite conference}}: Text "year 1998" ignored (help) - ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time.

Bibliography

- The International Journal of Astrobiology, published by Cambridge University Press, is the forum for practitioners in this interdisciplinary field.

- Astrobiology, published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., is a peer-reviewed journal that explores the origins of life, evolution, distribution, and destiny in the universe.

- Dick, Steven J. (2005). The Living Universe: NASA and the Development of Astrobiology. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813537339.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Grinspoon, David (2003). Lonely planets. The natural philosophy of alien life. New York: ECCO. ISBN 0060185406.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Jakosky, Bruce M. (2006). Science, Society, and the Search for Life in the Universe. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816526133.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Lunine, Jonathan I. (2005). Astrobiology. A Multidisciplinary Approach. San Francisco: Pearson Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0805380426.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gilmour, Iain (2004). An introduction to astrobiology. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-83736-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Ward, Peter (2000). Rare Earth: Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe. New York: Copernicus. ISBN 0387987010.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- International Astronomical Union Commission 51: Bioastronomy, official website

- Astrobiology Instant Expert on New Scientist

- Australian Centre for Astrobiology

- The Astrobiology Web

- Astrobiology Magazine

- NASA Astrobiology Institute

- Podcast Interview with NAI's Director Dr. Carl Pilcher

- European Astrobiology Network Association (EANA)

- Possible Connections Between Interstellar Chemistry and the Origin of Life on the Earth

- Scientists Find Clues That Life Began in Deep Space - NASA Astrobiology Institute

- Stars and Habitable Planets

- NASA-Macquarie University Pilbara Education Project

- Conditions for Life Everywhere

- Snaiad, a world-building project with creatures designed with evolutionary biology in mind.

- Astrobiology Lecture Course Network (a.y. 2005–2006)