Black Sunday (1977 film)

| Black Sunday | |

|---|---|

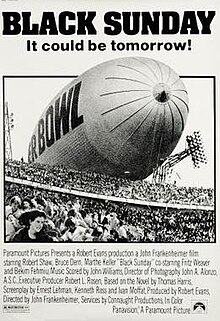

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Frankenheimer |

| Screenplay by | Ernest Lehman Kenneth Ross Ivan Moffat |

| Produced by | Robert Evans |

| Starring | Robert Shaw Bruce Dern Marthe Keller Fritz Weaver Bekim Fehmiu |

| Cinematography | John A. Alonzo |

| Edited by | Tom Rolf |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 143 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $15,769,322[1] |

Black Sunday is a 1977 American thriller film directed by John Frankenheimer, based on Thomas Harris' novel of the same name. The film was produced by Robert Evans, and stars Robert Shaw, Bruce Dern and Marthe Keller. It was nominated for the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Motion Picture in 1978.[2]

The inspiration of the story came from the Munich massacre, perpetrated by the Black September organization against Israeli athletes at the 1972 Summer Olympics, giving both the novel and film its title.[3]

Plot

Michael Lander is a pilot who flies the Goodyear Blimp over National Football League games to film them for network television. Secretly deranged by years of torture as a prisoner of war in Vietnam, he had a bitter court martial on his return and a failed marriage. He longs to commit suicide and to take with him as many as possible of the cheerful, carefree American civilians he sees from his blimp each weekend.

Lander conspires with Dahlia Iyad, an operative from the Palestinian terrorist group Black September, to launch a suicide attack using a bomb composed of plastique and a quarter million steel flechettes, housed on the underside of the gondola of the blimp, which they will detonate over the Miami Orange Bowl during Super Bowl X. Dahlia and Black September, in turn, intend the attack as a wake-up call for the American people, to turn their attention and the world's to the plight of the Palestinians.

American and Israeli intelligence, led by Mossad agent David Kabakov and Federal Bureau of Investigation agent Sam Corley, race to prevent the catastrophe. After discovering the recording Dahlia made, meant to be played after the attack, they piece together the path of the explosives into the country, and Dahlia's own movements.

The bomb-carrying blimp is chased by police helicopters as it approaches the stadium. Kabakov kills Lander and Iyad, but not before Lander lights the fuse to the blimp's bomb. Kabakov lowers himself from the helicopter to the blimp, hooks it up and hauls it out of the stadium and over the ocean where it blows up.

Cast

As appearing in Black Sunday (main roles and screen credits identified):[4]

- Robert Shaw as Major David Kabakov

- Bruce Dern as Michael Lander

- Marthe Keller as Dahlia Iyad

- Fritz Weaver as Sam Corley

- Steven Keats as Robert Moshevsky

- Bekim Fehmiu as Mohammed Fasil

- Michael V. Gazzo as Muzi

- William Daniels as Harold Pugh

- Walter Gotell as Colonel Riat

- Victor Campos as Nageeb

- Joe Robbie as Himself

- Robert Wussler as Himself

- Pat Summerall as Himself

- Tom Brookshier as Himself

- Walter Brooke as Fowler

- James Jeter as Watchman

- Clyde Kusatsu as Freighter Captain

- Tom McFadden as Farley

- Robert Patten as Vickers

- Than Wyenn as Israeli Ambassador

Production

The novel is the only one by author Thomas Harris not to involve the serial killer Hannibal Lecter.[5] In his introduction to the new printing of the novel, Harris states that the driven, focused character of terrorist Dahlia Iyad was actually an inspiration for and precursor to Clarice Starling in his later Lecter novels.[6]

The film was produced by former Paramount Pictures chief Robert Evans. He had earlier produced Chinatown (1974) and Marathon Man (1976).[7] Director John Frankenheimer's frequent line producer Robert L. Rosen was credited as executive producer.

As it hinged on filming a real Goodyear Blimp at a real Super Bowl, there were many challenges. Luckily, Frankenheimer had a good relationship with the heads of The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company as a result of working with them on his earlier film Grand Prix.[8] Frankenheimer states in Charles Champlin's biography that he helped convince Goodyear by telling them that if they declined, he would rent the only other large blimp in the world from Germany, paint it silver, and people would assume it was theirs anyway.[9]

Evans helped secure the unprecedented cooperation of the National Football League and the production was allowed to film at Super Bowl X and shoot extensive footage with the principal actors for the film's final half hour as the Dallas Cowboys played the Pittsburgh Steelers.[10]

Blimps

Goodyear granted use of all three of its U.S.-based blimps for Black Sunday, with a nose section recreated for filming its appearance over the stadium. The blimps were flown by company pilots, Nick Nicolary and Corky Belanger Sr., among the five pilots who were involved in the production.[11] The landing and hijacking scenes were photographed at the Goodyear airship base in Carson, California with Columbia (N3A); a short scene in the Spring, Texas base with the America (N10A), and the Miami, Florida Super Bowl scenes with the Mayflower (N1A), which was then based on Watson Island across the Port of Miami.[12]

While Goodyear allowed the use of their airship fleet, they did not allow the "Goodyear Wingfoot" logo (prominently featured on the side of the blimp) to be used in the advertising or the poster for the film. Thus, the words "Super Bowl" are featured in place of the logo on the blimp in the advertising collateral.[13]

Music

The film's score was composed by John Williams. In January 2010, Film Score Monthly issued a limited edition of 10,000 copies of the previously unreleased soundtrack, remixed from the original masters.[14]

Reception

Black Sunday was among the highest-scoring films ever in the history of Paramount Pictures test screenings, and was widely predicted in the industry as a second Jaws. When it came out in March 1977, however, the film fell short of expectations.

John Frankenheimer later said the film was hurt by the fact another movie about terrorism at a championship football game, Two-Minute Warning, had come out just beforehand and performed poorly. He also blamed the fact the movie was banned in Germany and Japan.[15]

Still, it became regarded by some as one of Frankenheimer's best thrillers. Although receiving generally favorable critical reviews, Black Sunday was appreciated more for its technical virtues and storyline than its character development. Reviewer Vincent Canby from The New York Times tried to rationalize his reaction: "I suspect it has to do with the constant awareness that the story is more important than anybody in it ... The characters don't motivate the drama in any real way.[7] In a later review, Christopher Null, took exception and identified the one key character who drove the plot, "... Black Sunday is distinguished by its unique focus not on the hero but on the villain: Bruce Dern ..." [16]

Homage

Quentin Tarantino has said in interviews that the sequence in Kill Bill: Volume 1 where Daryl Hannah attempts to kill The Bride in disguise as a nurse is an homage to a similar sequence in Black Sunday. More specifically, he said the fact that the sequence in his film is done with split-screens is actually an homage to the trailer for Black Sunday, which shows shots from the sequence in that manner, unlike in the actual film.[17]

Satire

Black Sunday was called "Blimp Sunday" in the December 1977 issue of Mad Magazine #195, written by Dick DeBartolo with art from Mort Drucker.[18]

References

Notes

- ^ http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=blacksunday.htm

- ^ "The Edgar® Award Winners And Nominees Award Category." Mystery Writers of America. Retrieved: August 20, 2012.

- ^ "Black Sunday (1977)." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: August 21, 2012.

- ^ "Credits: Black Sunday (1977)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: February 3, 2012.

- ^ Cowley, Jason. "Profile: Thomas Harris, Creator of a monstrous hit. The Guardian, November 19, 2008.

- ^ Dern and Crane 2007, p. 155.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent. "Black Sunday (1977)." The New York Times, April 1, 1977.

- ^ Pomerance and Palmer 2011, p. 106.

- ^ Champlin 1995, p. 147.

- ^ Pomerance and Palmer 2011, pp. 107–108.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Goodyear Blimp." World’s Strangest, 2008. Retrieved: February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Goodyear News." Goodyear, April 3, 2011. Retrieved: February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Black Sunday." ohio.com. Retrieved: February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Black Sunday." Film Score Monthly. Retrieved: November 4, 2012.

- ^ Mann, R. (1982, Sep 26). FRANKENHEIMER SPEEDS ON. Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/153254062?accountid=13902

- ^ Null, Christopher. "Black Sunday." Filmcritic.com, October 11, 2003.

- ^ Rose, Steve. "Found: where Tarantino gets his ideas". The Guardian, April 6, 2004. Retrieved: February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Issue #195 at MadCoverSite.com"

Bibliography

- Champlin, Charles, ed. John Frankenheimer: A Conversation With Charles Champlin. Bristol, UK: Riverwood Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-880756-09-6.

- Dern, Bruce and Robert Crane. Things I've Said, But Probably Shouldn't Have ... Indianapolis, Indiana: Wiley, 2007. ISBN 978-0-470-10637-2.

- Pomerance, Murray and R. Barton Palmer, eds. A Little Solitaire: John Frankenheimer and American Film. Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-8135-5060-2.

External links

- Black Sunday at IMDb

- Black Sunday at the TCM Movie Database

- Black Sunday at AllMovie

- Black Sunday at Rotten Tomatoes

- Home Movies of Orange Bowl Scene on YouTube Shot by an extra during a day of filming at The Miami Orange Bowl

- 1977 films

- 1970s action thriller films

- American action thriller films

- American disaster films

- American films

- American football films

- American mystery films

- Aviation films

- Dallas Cowboys

- English-language films

- Film scores by John Williams

- Films about terrorism

- Films directed by John Frankenheimer

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films set in Lebanon

- Films set in Los Angeles, California

- Films set in Miami, Florida

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Neo-noir

- Pittsburgh Steelers in popular culture

- Super Bowl