Board game

A board game is a game that involves counters or pieces moved or placed on a pre-marked surface or "board", according to a set of rules. Games can be based on pure strategy, chance (e.g. rolling dice) or a mixture of the two, and usually have a goal that a player aims to achieve. Early board games represented a battle between two armies, and most current board games are still based on defeating opposing players in terms of counters, winning position or accrual of points (often expressed as in-game currency).

There are many different types and styles of board games. Their representation of real-life situations can range from having no inherent theme, as with checkers, to having a specific theme and narrative, as with Cluedo. Rules can range from the very simple, as in Tic-tac-toe, to those describing a game universe in great detail, as in Dungeons & Dragons (although most of the latter are role-playing games where the board is secondary to the game, helping to visualize the game scenario).

The amount of time required to learn to play or master a game varies greatly from game to game. Learning time does not necessarily correlate with the number or complexity of rules; some games, such as chess or Go, have simple rulesets while possessing profound strategies.

History

Board games have been played in most cultures and societies throughout history; some even pre-date literacy skill development in the earliest civilizations. [citation needed] A number of important historical sites, artifacts, and documents shed light on early board games. These include:

- Jiroft civilization gameboards

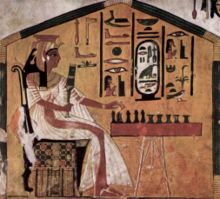

- Senet has been found in Predynastic and First Dynasty burials of Egypt, c. 3500 BC and 3100 BC respectively.[1] Senet is the oldest board game known to have existed, and was pictured in a fresco found in Merknera's tomb (3300–2700 BC).[2]

- Mehen, another ancient board game from Predynastic Egypt

- Go, an ancient strategic board game originating in China

- Patolli, a board game originating in Mesoamerica played by the ancient Aztec

- Royal Game of Ur, the Royal Tombs of Ur contain this game, among others

- Buddha games list, the earliest known list of games

- Pachisi and Chaupar, ancient board games of India

Timeline

- c. 3500 BC: Senet is played in Predynastic Egypt as evidenced by its inclusion in burial sites;[1] also depicted in the tomb of Merknera.

- c. 3000 BC: The Mehen board game from Predynastic Egypt, played with lion-shaped game pieces and marbles.

- c. 3000 BC: Ancient backgammon set, found in the Burnt City in Iran.[3][4]

- c. 2560 BC: Board of the Royal Game of Ur (found at Ur Tombs)

- c. 2500 BC: Paintings of Senet and Han being played depicted in the tomb of Rashepes[citation needed]

- c. 1500 BC: Painting of board game at Knossos.[5]

- c. 500 BC: The Buddha games list mentions board games played on 8 or 10 rows.

- c. 500 BC: The earliest reference to Pachisi in the Mahabharata, the Indian epic.

- c. 400 BC: Two ornately decorated liubo gameboards from a royal tomb of the State of Zhongshan in China.[6]

- c. 400 BC: The earliest written reference to Go (weiqi) in the historical annal Zuo Zhuan. Go is also mentioned in the Analects of Confucius (c. 5th century BC).[7]

- 116–27 BC: Marcus Terentius Varro's Lingua Latina X (II, par. 20) contains earliest known reference to Latrunculi[8] (often confused with Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum, Ovid's game mentioned below).

- 1 BC – 8 AD: Ovid's Ars Amatoria contains earliest known reference to Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum.

- 1 BC – 8 AD: The Roman Game of kings is a game of which little is known, and is more or less contemporary with the Latrunculi.

- c. 43 AD: The Stanway Game is buried with the Druid of Colchester.[9]

- c. 200 AD: A stone Go board with a 17×17 grid from a tomb at Wangdu County in Hebei, China.[10]

- 220–265: Backgammon enters China under the name t'shu-p'u (Source: Hun Tsun Sii)[citation needed]

- c. 400 onwards: Tafl games played in Northern Europe.[11]

- c. 600: The earliest references to chaturanga written in Subandhu's Vasavadatta and Banabhatta's Harsha Charitha early Indian books.[citation needed]

- c. 600: The earliest reference to shatranj written in Karnamak-i-Artakhshatr-i-Papakan.[citation needed]

- c. 700: Date of the oldest evidence of Mancala games, found in Matara, Eritrea and Yeha.

- c. 1283: Alfonso X of Castile in Spain commissioned Libro de ajedrez, dados, y tablas (Libro de los Juegos (The Book of Games)) translated into Castilian from Arabic and added illustrations with the goal of perfecting the work.[12][13]

- 1759: A Journey Through Europe published by John Jefferys, the earliest board game with a designer whose name is known.

- 1874: Parcheesi is trademarked by Selchow & Righter.

- c. 1930: Monopoly stabilises into the version that is currently popular.

- 1938: The first version of Scrabble published by Alfred Butts under the name "Criss-Crosswords".

- 1957: Risk is released.

- 1970: The code-breaking board game Mastermind is designed by Mordecai Meirowitz.

- c. 1980: German-style board games begin to develop as a genre.

Many board games are now available as video games, which can include the computer itself as one of several players, or as a sole opponent. The rise of computer use is one of the reasons said to have led to a relative decline in board games.[citation needed] Many board games can now be played online against a computer and/or other players. Some websites allow play in real time and immediately show the opponents' moves, while others use email to notify the players after each move (see the links at the end of this article). [citation needed] Modern technology (the internet and cheaper home printing) has also influenced board games via the phenomenon of print-and-play board games that you buy and print yourself.

Some board games make use of components in addition to—or instead of—a board and playing pieces. Some games use CDs, video cassettes, and, more recently, DVDs in accompaniment to the game.[citation needed]

Around the year 2000 the board gaming industry began to grow with companies such as Fantasy Flight Games, Z-Man Games, or Indie Boards and Cards, churning out new games which are being sold to a growing (and slightly massive) audience worldwide.[14]

In America

Colonial America

In seventeenth and eighteenth century colonial America, the agrarian life of the country left little time for game playing though draughts (checkers), bowling, and card games were not unknown. The Pilgrims and Puritans of New England frowned on game playing and viewed dice as instruments of the devil. When the Governor William Bradford discovered a group of non-Puritans playing stool-ball, pitching the bar, and pursuing other sports in the streets on Christmas Day, 1622, he confiscated their implements, reprimanded them, and told them their devotion for the day should be confined to their homes.

Early United States

In Thoughts on Lotteries (1826) Thomas Jefferson wrote, "Almost all these pursuits of chance [i.e., of human industry] produce something useful to society. But there are some which produce nothing, and endanger the well-being of the individuals engaged in them or of others depending on them. Such are games with cards, dice, billiards, etc. And although the pursuit of them is a matter of natural right, yet society, perceiving the irresistible bent of some of its members to pursue them, and the ruin produced by them to the families depending on these individuals, consider it as a case of insanity, quoad hoc, step in to protect the family and the party himself, as in other cases of insanity, infancy, imbecility, etc., and suppress the pursuit altogether, and the natural right of following it. There are some other games of chance, useful on certain occasions, and injurious only when carried beyond their useful bounds. Such are insurances, lotteries, raffles, etc. These they do not suppress, but take their regulation under their own discretion."

The board game, Traveller's Tour Through the United States was published by New York City bookseller F. Lockwood in 1822 and today claims the distinction of being the first board game published in the United States.

As the United States shifted from agrarian to urban living in the nineteenth century, greater leisure time and a rise in income became available to the middles class. The American home, once the center of economic production, became the locus of entertainment, enlightenment, and education under the supervision of mothers. Children were encouraged to play board games that developed literacy skills and provided moral instruction.[15]

The earliest board games published in the United States were based upon Christian morality. The Mansion of Happiness (1843), for example, sent players along a path of virtues and vices that led to the Mansion of Happiness (Heaven).[15] The Game of Pope or Pagan, or The Siege of the Stronghold of Satan by the Christian Army (1844) pitted an image on its board of a Hindu woman committing suttee against missionaries landing on a foreign shore. The missionaries are cast in white as "the symbol of innocence, temperance, and hope" while the pope and pagan are cast in black, the color of "gloom of error, and...grief at the daily loss of empire".[16]

Commercially-produced board games in the middle nineteenth century were monochrome prints laboriously hand-colored by teams of low paid young factory women. Advances in paper making and printmaking during the period enabled the commercial production of relatively inexpensive board games. The most significant advance was the development of chromolithography, a technological achievement that made bold, richly colored images available at affordable prices. Games cost as little as US$.25 for a small boxed card game to $3.00 for more elaborate games.

American Protestants believed a virtuous life led to success, but the belief was challenged mid-century when Americans embraced materialism and capitalism. The accumulation of material goods was viewed as a divine blessing. In 1860, The Checkered Game of Life rewarded players for mundane activities such as attending college, marrying, and getting rich. Daily life rather than eternal life became the focus of board games.The game was the first to focus on secular virtues rather than religious virtues,[15] and sold 40,000 copies its first year.[17]

Game of the District Messenger Boy, or Merit Rewarded is a board game published in 1886 by the New York City firm of McLoughlin Brothers. The game is a typical roll-and-move track board game. Players move their tokens along the track at the spin of the arrow toward the goal at track's end. Some spaces on the track will advance the player while others will send him back.

In the affluent 1880s, Americans witnessed the publication of Algeresque rags to riches games that permitted players to emulate the capitalist heroes of the age. One of the first such games, The Game of the District Messenger Boy, encouraged the idea that the lowliest messenger boy could ascend the corporate ladder to its topmost rung. Such games insinuated that the accumulation of wealth brought increased social status.[15] Competitive capitalistic games culminated in 1935 with Monopoly, the most commercially successful board game in United States history.[18]

McLoughlin Brothers published similar games based on the telegraph boy theme including Game of the Telegraph Boy, or Merit Rewarded (1888). Greg Downey notes in his essay, "Information Networks and Urban Spaces: The Case of the Telegraph Messenger Boy" that families who could afford the deluxe version of the game in its chromolithographed, wood-sided box would not "have sent their sons out for such a rough apprenticeship in the working world."[19]

Psychology

While there has been a fair amount of scientific research on the psychology of older board games (e.g., chess, Go, mancala), less has been done on contemporary board games such as Monopoly, Scrabble, and Risk.[20] Much research has been carried out on chess, in part because many tournament players are publicly ranked in national and international lists, which makes it possible to compare their levels of expertise. The works of Adriaan de Groot, William Chase, Herbert A. Simon, and Fernand Gobet have established that knowledge, more than the ability to anticipate moves, plays an essential role in chess-playing. This seems to be the case in other traditional games such as Go and Oware (a type of mancala game), but data is lacking in regard to contemporary board games. [citation needed]

Additionally, board games can be therapeutic. Bruce Halpenny, a games inventor said when interviewed about his game, “With crime you deal with every basic human emotion and also have enough elements to combine action with melodrama. The player’s imagination is fired as they plan to rob the train. Because of the gamble they take in the early stage of the game there is a build up of tension, which is immediately released once the train is robbed. Release of tension is therapeutic and useful in our society, because most jobs are boring and repetitive.”[21]

Linearly arranged board games have been shown to improve children's spatial numerical understanding. This is because the game is similar to a number line in that they promote a linear understanding of numbers rather than the innate logarithmic one.[22]

Luck, strategy and diplomacy

Most board games involve both luck and strategy. But an important feature of them is the amount of randomness/luck involved, as opposed to skill. Some games, such as chess, depend almost entirely on player skill. But many children's games are mainly decided by luck: e.g. Candy Land and Chutes and Ladders require no decisions by the players. A player may be hampered by a few poor rolls of the dice in Risk or Monopoly, but over many games a good player will win more often. While some purists consider luck not to be a desirable component of a game, others counter that elements of luck can make for far more diverse and multi-faceted strategies, as concepts such as expected value and risk management must be considered.

A second feature is the game information available to players. Some games (chess being the classic example) are perfect information games: every player has complete information on the state of the game. In other games, such as Tigris and Euphrates, some information is hidden from players. This makes finding the best move more difficult, but also requires the players to estimate probabilities by the players. Tigris and Euphrates also has completely deterministic action resolution.[clarification needed]

Another important feature of a game is the importance of diplomacy, i.e. players making deals with each other. A game of solitaire, for obvious reasons, has no player interaction. Two player games usually do not involve diplomacy (cooperative games being the exception). Thus, negotiation generally features only in games for three or more people. An important facet of The Settlers of Catan, for example, is convincing people to trade with you rather than with other players. In Risk, two or more players may team up against others. Easy diplomacy involves convincing other players that someone else is winning and should therefore be teamed up against. Advanced diplomacy (e.g. in the aptly named game Diplomacy) consists of making elaborate plans together, with the possibility of betrayal.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Luck may be introduced into a game by a number of methods. The most common method is the use of dice, generally six-sided. These can decide everything from how many steps a player moves their token, as in Monopoly, to how their forces fare in battle, such as in Risk, or which resources a player gains, such as in The Settlers of Catan. Other games such as Sorry! use a deck of special cards that, when shuffled, create randomness. Scrabble does something similar with randomly picked letters. Other games use spinners, timers of random length, or other sources of randomness. Trivia games have a great deal of randomness based on the questions a player has to answer. German-style board games are notable for often having rather less of a luck factor than many North American board games.

Common terms

Although many board games have a jargon all their own, there is a generalized terminology to describe concepts applicable to basic game mechanics and attributes common to nearly all board games.

- Gameboard (or simply board)—the (usually quadrilateral) surface on which one plays a board game. The namesake of the board game, gameboards would seem to be a necessary and sufficient condition of the genre, though card games that do not use a standard deck of cards (as well as games that use neither cards nor a gameboard) are often colloquially included. Most games use a standardized and unchanging board (chess, Go, and backgammon each have such a board), but many games use a modular board whose component tiles or cards can assume varying layouts from one session to another, or even while the game is played.

- Game piece (or gamepiece, counter, token, bit, meeple, mover, pawn, man, playing piece, player piece)—a player's representative on the gameboard made of a piece of material made to look like a known object (such as a scale model of a person, animal, or inanimate object) or otherwise general symbol. Each player may control one or more game pieces. Some games involve commanding multiple game pieces (or units), such as chess pieces or Monopoly houses and hotels, that have unique designations and capabilities within the parameters of the game; in other games, such as Go, all pieces controlled by a player have the same capabilities. In some modern board games, such as Clue, there are other pieces that are not a player's representative (i.e. weapons). In some games, pieces may not represent or belong to any particular player. See also: Counter (board wargames)

- Jump (or leap)—to bypass one or more game pieces or spaces. Depending on the context, jumping may also involve capturing or conquering an opponent's game piece. (See also: capture)

- Space (or square)—a physical unit of progress on a gameboard delimited by a distinct border. Alternatively, a unique position on the board on which a game piece may be located while in play. (In Go, for example, the pieces are placed on intersections of lines on the grid, not in the areas bounded by borders, as in chess.) (See also: movement)

- Hex (or cell)—in hexagon-based board games, this is the common term for a standard space on the board. This is most often used in wargaming, though many abstract strategy games such as Abalone, Agon, hexagonal chess, and connection games use hexagonal layouts.

- Card—a piece of cardboard often bearing instructions, and usually chosen randomly from a deck by shuffling.

- Deck—a stack of cards.

- Capture—a method that removes another player's game piece(s) from the board. For example: in checkers, if a player jumps the opponent's piece, that piece is captured.

Categories

There are a number of different categories that board games can be broken up into, although considerable overlap exists, and a game may belong in several categories. The following is a list of some of the most common:

- Abstract strategy games—like chess, Tafl games, Checkers, Go, Reversi, or modern games such as Abalone, Stratego, or Hive

- Alignment games—like Renju, Gomoku, Connect6, Nine Men's Morris, or Tic-tac-toe

- Chess variants—like Grand Chess or xiangqi

- Configuration games—like Lines of Action, Hexade, or Entropy

- Connection games—like Havannah or Hex

- Cooperative games—like Max, Caves and Claws or Pandemic

- Dexterity games—like Tumblin' Dice or Pitch Car

- Educational games—like Arthur Saves the Planet, Cleopatra and the Society of Architects, or Shakespeare: The Bard Game

- Elimination games—like Yoté, Alquerque, Fanorona, or draughts

- Family games—like Roll Through the Ages, Birds on a Wire, or For Sale

- German-style board games or Eurogames—like The Settlers of Catan, Carson City or Puerto Rico

- Historical simulation games—like Through the Ages or Railways of the World

- Large multiplayer games—like Take It Easy or Swat (2010)

- Mancala games—like Oware or The Glass Bead Game

- Musical games—like Spontuneous

- Paper-and-pencil games—like Tic-tac-toe or Dots and Boxes

- Position games (no captures; win by leaving the opponent unable to move)—like Mū Tōrere or the L game

- Race games—like Pachisi, backgammon, or Worm Up

- Roll-and-move games—like Monopoly or Life

- Share-buying games—in which players buy stakes in each other's positions; typically longer economic-management games

- Single-player puzzle games—like Peg solitaire or Sudoku

- Spiritual development games (games that have no winners or losers)—like Transformation Game or Psyche's Key

- Stacking games—like Lasca or DVONN

- Territory games—like Go or Reversi

- Train games—like Ticket to Ride, Steam, or 18xx

- Trivia games—like Trivial Pursuit

- Two-player-only games—like En Garde or Dos de Mayo

- Unequal forces (or "hunt") games—like Fox and Geese or Tablut

- Wargames—ranging from Risk or Diplomacy or Axis & Allies, to Attack! or Conquest of the Empire

- Word games—like Scrabble, Boggle, or What's My Word? (2010)

See also

- Going Cardboard (Documentary, including interviews with game designers and game publishers)

- Interactive movie - DVD games

- History of games

- List of board games

- List of game manufacturers

- Mind sport

- Tabletop game

- Snakes and Lattes, a board game café

- BoardGameGeek, a board game community and website database

References

- ^ a b Piccione, Peter A. (1980). "In Search of the Meaning of Senet". Archaeology: 55–58. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "''Okno do svita deskovych her''". Hrejsi.cz. 1998-04-27. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

- ^ "World's Oldest Backgammon Discovered In Burnt City". Payvand News. December 4, 2004. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Schädler , Dunn-Vaturi, Ulrich , Anne-Elizabeth. "BOARD GAMES in pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brumbaugh, Robert S. (1975). "The Knossos Game Board". American Journal of Archaeology. 79 (2). Archaeological Institute of America: 135–137. doi:10.2307/503893. JSTOR 503893. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica (1996). Mysteries of Ancient China. London: British Museum Press. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-7141-1472-3.

- ^ "Confucius". Senseis.xmp.net. 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

- ^ "Varro: Lingua Latina X". Thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

- ^ Games Britannia – 1. Dicing with Destiny, BBC Four, 1:05am Tuesday 8th December 2009

- ^ John Fairbairn's Go in Ancient China[dead link]

- ^ Murray 1951, pp.56, 57.

- ^ Burns, Robert I. "Stupor Mundi: Alfonso X of Castile, the Learned." Emperor of Culture: Alfonso X the Learned of Castile and His Thirteenth-Century Renaissance. Ed. Robert I. Burns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania P, 1990. 1–13.

- ^ Sonja Musser Golladay, "Los Libros de Acedrex Dados E Tablas: Historical, Artistic and Metaphysical Dimensions of Alfonso X’s Book of Games" (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007), 31. Although Golladay is not the first to assert that 1283 is the finish date of the Libro de Juegos, the a quo information compiled in her dissertation consolidates the range of research concerning the initiation and completion dates of the Libro de Juegos.

- ^ Smith, Quinti (2012). "The Board Game Golden Age". Retrieved 2013-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Jensen, Jennifer (2003). "Teaching Success Through Play: American Board and Table Games, 1840-1900". Magazine Antiques. bnet. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ Fessenden, Tracy (2007). Culture and Redemption: Religion, the Secular, and American Literature. Princeton University Press. p. 271. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ Hofer, Margaret K. (2003). The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board & Table Games. Princeton Architectural Press. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ Weber, Susan, and Susie McGee (n.d.). "History of the Game Monopoly". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Downey, Greg (1999-11). "Information Networks and Urban Spaces: The Case of the Telegraph Messenger Boy". Antenna. Mercurians. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) [dead link] - ^ de Voogt, Alex, & Retschitzki, Jean (2004). Moves in mind: The psychology of board games. Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-336-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stealing the show. Toy Retailing News, Volume 2 Number 4 (December 1976), p. 2

- ^ "Playing Linear Number Board Games—But Not Circular Ones—Improves Low-Income Preschoolers' Numerical Understanding" (PDF).

- ^ Murray 1913, p.80

Further reading

- Austin, Roland G. "Greek Board Games." Antiquity 14. September 1940: 257–271

- Bell, Robert Charles. The Boardgame Book. London: Bookthrift Company, 1979.

- Bell, Robert Charles. Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-486-23855-5

- Reprint: New York: Exeter Books, 1983.

- Falkener, Edward. Games Ancient and Oriental, and How To Play Them. Longmans, Green and Co., 1892.

- Fiske, Willard. Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature—with historical notes on other table-games. Florentine Typographical Society, 1905.

- Gobet, Fernand; de Voogt, Alex, & Retschitzki, Jean (2004). Moves in mind: The psychology of board games. Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-336-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Golladay, Sonja Musser, "Los Libros de Acedrex Dados E Tablas: Historical, Artistic and Metaphysical Dimensions of Alfonso X’s Book of Games" (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007)

- Gordon, Stewart (2009). "The Game of Kings". Saudi Aramco World. 60 (4). Houston: Aramco Services Company: 18–23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) (PDF version) - Murray, Harold. A History of Chess. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1913.

- Murray, Harold. A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess. Gardners Books, 1969.

- Parlett, David. Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-212998-8

- Rollefson, Gary O., "A Neolithic Game Board from Ain Ghazal, Jordan," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 286. (May 1992), pp. 1–5.

- Sackson, Sid. A Gamut of Games. Arrow Books, 1983. ISBN 0-09-153340-6

- Reprint: Dover Publications, 1992. ISBN 0-486-27347-4

- Schmittberger, R. Wayne. New Rules for Classic Games. John Wiley & Sons, 1992. ISBN 0-471-53621-0

- Reprint: Random House Value Publishing, 1994. ISBN 0-517-12955-8