Bobby Fischer

| Bobby Fischer | |

|---|---|

| File:Bobby Fischer - March, 2005 (7347390).jpg | |

| Full name | Robert James Fischer |

| Country | |

| Title | Grandmaster |

| World Champion | 1972-1975 (FIDE) |

| Peak rating | 2785 (July 1972) |

Robert James "Bobby" Fischer (born March 9, 1943) is a United States-born chess Grandmaster who became famous as a teenager for his chess-playing ability, and in 1972 became the only US-born chessplayer to become the official World Chess Champion. In 1975 he refused to defend the title when FIDE, the international chess federation, refused to accept his conditions for a title defense. He is a regular candidate in discussions of who is the greatest chess player of all time.[1]

Fischer now lives in Iceland, and has also been accused by many of anti-Americanism and anti-Semitism, despite his being of Jewish descent.[2]

Early years

Robert James Fischer was born at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. His mother, Regina Wender, was a naturalized American citizen of German Jewish[3] descent, born in Switzerland but raised in St. Louis, Missouri, and later a teacher, a registered nurse and a physician.[4] Fischer's father was listed on the birth certificate as Wender's first husband, Hans-Gerhardt Fischer, a German biophysicist. The couple married in 1933 in Moscow, U.S.S.R., where Wender was studying medicine at the First Moscow Medical Institute. However, a 2002 article by Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson of The Philadelphia Inquirer suggests that Paul Nemenyi, a Jewish Hungarian physicist, may have been Fischer's biological father. Nicholas and Benson quote an FBI report that states that Regina Fischer returned to the United States in 1939 while Hans-Gerhardt Fischer never entered the United States.[5] Hans-Gerhardt and Regina Fischer divorced in 1945 when Bobby was two years old, and he grew up with his mother and older sister, Joan. In 1948, the family moved to Mobile, Arizona, where Regina taught in an elementary school. The following year they moved to Brooklyn, New York, where Regina worked as an elementary school teacher and nurse.

In May 1949, the six-year-old Fischer learned how to play chess from instructions found in a chess set that his sister had bought at a candy store below their Brooklyn apartment. He saw his first chess book a month later. For over a year he played chess on his own. At age seven, he joined the Brooklyn Chess Club and was taught by its president, Carmine Nigro. He later joined the Manhattan Chess Club. Other important early influences were provided by Master and chess journalist Hermann Helms and Grandmaster Arnold Denker. Denker served as a mentor to young Bobby, and often took him to watch professional hockey games at Madison Square Garden, to cheer the New York Rangers; Denker wrote that Bobby enjoyed those treats and never forgot them; the two became lifelong friends (The Bobby Fischer I Knew And Other Stories, by Arnold Denker and Larry Parr, Hypermodern Press 1995, p. 107). When Fischer was thirteen, his mother asked John W. Collins to be his chess tutor. Collins had coached several top players, including future grandmasters Robert Byrne and William Lombardy. Fischer spent much time at Collins' house, and some have described Collins as a father figure for Fischer. The Hawthorne Chess Club was the name for the group which Collins coached. Fischer also was involved with the Log Cabin Chess Club.

Bobby Fischer attended Erasmus Hall High School together with Barbra Streisand[6], though he later dropped out in 1959 when he turned 16. Many teachers remembered him as difficult. When his chess feats mounted, the student council of Erasmus Hall awarded him a gold medal for his chess achievements (source: Profile of a Prodigy, by Frank Brady (1965)).

Young champion (1956-57)

Fischer's first real triumph was winning the United States Junior Chess Championship in July 1956; he scored 8.5/10 at Philadelphia to become the youngest-ever junior champion,[7], a record which still stands today. In the 1956 U.S. Open Chess Championship at Oklahoma City, Fischer scored 8.5/12 to tie for 4-8th places, with Arthur Bisguier winning.[8] Then he played in the first Canadian Open Chess Championship at Montreal 1956, scoring 7/10 to tie for 8-12th places, as Larry Evans won.[9] Fischer's famous game from the 3rd Rosenwald Trophy tournament at New York 1956, against Donald Byrne, who later became an International Master, was called "The Game of the Century" by Hans Kmoch. At the age of 12, he was awarded the U.S. title of National Master, then the youngest ever.[10]

In 1957, Fischer first successfully defended his U.S. Junior title, scoring 8.5/9 at San Francisco.[11] Then he won the U.S. Open Chess Championship at Cleveland on tie-breaking points over Arthur Bisguier, scoring 10/12; he remains the youngest-ever U.S. Open champion.[12] Fischer defeated the young Filipino Master Rodolfo Tan Cardoso by 6-2 in a match in New York.[13] He next won the New Jersey Open Championship.[14] From these triumphs, Fischer was given entry into the invitational U.S. Chess Championship at New York. Many thought he was too weak, and predicted that he would finish last. Instead, he won, with 10.5/13, becoming in January 1958, at age 14, the youngest U.S. champion ever (this record still stands in 2007). He earned the title of International Master with this victory, becoming the youngest player ever to achieve this level (a record since broken).

First World title attempts (1958-59)

Fischer's victory qualified him to participate in the 1958 Portorož Interzonal, the next step toward challenging the World Champion. At 15, he was the youngest-ever Interzonal player. The top six finishers in the Interzonal would qualify for the Candidates Tournament, but few thought the youngster had much chance of this. Again he surprised the pundits, tying for 5-6th places, with 12/20, after a strong finish.[15] This made Fischer the youngest person ever to qualify for the Candidates, a record which stood until 2005 (it was broken under a different setup[16] by Magnus Carlsen), and also earned him the title of Grandmaster, making him at that time the youngest grandmaster in history.

Before the Candidates' tournament, he competed in 1959 in strong International tournaments at Mar del Plata, Argentina; Santiago, Chile; and Zurich, Switzerland. In all three events, he scored well, showing that he was of true grandmaster strength.

At the age of 16, Fischer finished a creditable equal fifth out of eight at the Candidates Tournament held in Bled/Zagreb/Belgrade, Yugoslavia in 1959. He scored 12.5/28 but was outclassed by tournament winner Mikhail Tal, who won all four of their individual games.[17]

Unsuccessful World Championship contender (1960-62)

In 1960, Fischer tied for first with the young Soviet star Boris Spassky at the strong Mar del Plata tournament in Argentina, with the two well ahead of the rest of the field, scoring 13.5/15 (Wade & O'Connell 1972:183). Fischer lost only to Spassky, and this was the start of their relationship, which began on a friendly basis and stayed that way, in spite of Fischer's troubles on the board against Spassky. Fischer struggled in the subsequent Buenos Aires tournament, finishing with 8.5/19. The tournament was won by Soviet Viktor Korchnoi and Samuel Reshevsky, the many-time U.S. Champion and one of the world's strongest players, each scoring 13/19 (Wade & O'Connell 1972:189). This was the only real failure of Fischer's competitive career.

In 1961, Fischer started a 16-game match with Reshevsky. The match was split between New York and Los Angeles. Despite Fischer's meteoric rise, the veteran Reshevsky (born in 1911, 32 years older than Fischer) was considered the favorite, since not only did he have much more match experience, but he had never lost a set match in his life. After 11 games and a tie score (2 wins apiece with 7 draws), the match ended due to a dispute between Fischer and match organizer and sponsor Jacqueline Piatigorsky. The hard-fought struggle, with many games being adjourned, had delayed the original match schedule, causing some logistical challenges for site bookings. Mrs. Piatigorsky's husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a world-class concert cellist, was giving a concert later in the afternoon of the scheduled 12th game. Mrs. Piatigorsky, who wanted to attend the concert, as well as the chess game, rescheduled the 12th game to start at 11 a.m., apparently without getting Fischer's approval. Fischer, who liked to sleep late, objected, and eventually abandoned the match after being unable to come to an agreement with the organizer. Reshevsky received the winner's share of the prizes (Profile of a Prodigy, by Frank Brady (1965)). Fischer later made up with Mrs. Piatigorsky by accepting an invitation to the 2nd Piatigorsky Cup, Santa Monica 1966, which she helped to sponsor.

Fischer was second behind former World Champion Tal at Bled 1961, a super-strong tournament. He defeated Tal head-to-head for the first time, scored 3.5/4 against the Soviet contingent, and finished as the only unbeaten player, with 13.5/19 (Wade & O'Connell 1972:199).

In the next World Championship cycle, Fischer won the 1962 Stockholm Interzonal by 2.5 points, scoring 17.5/22, making him one of the favorites for the Candidates tournament in Curaçao, which began soon afterwards. However, he had a disappointing tournament, finishing fourth out of eight with a 14-13 score. The result nonetheless established Fischer, at 19, as the strongest non-Soviet player in the world. Tal fell very ill during the tournament, and had to withdraw before completion. Fischer, a friend of Tal's, was the only player who visited him in the hospital (Profile of a Prodigy, by Frank Brady (1965)).

Following his failure in the 1962 Candidates (at which five of the eight players were from the Soviet Union), Fischer asserted that three of the Soviet players had an agreement to draw their games in order to concentrate on playing against him, and also that a fourth, Victor Korchnoi, had been forced to throw games to ensure a Soviet player won. It is generally thought that the former accusation is correct, but not the latter. (This is discussed further at the World Chess Championship 1963 article).

U.S. Championships results

Fischer played in eight United States Chess Championships, each held in New York City, winning every one. His scores were: 1957-58: 10.5/13; 1958-59: 8.5/11; 1959-60: 9/11; 1960-61: 9/11; 1962-63: 8/11; 1963-64: 11/11; 1965-66: 8.5/11; 1966-67: 9.5/11. The total is 74/90, for 82.2 percent, with only three losses.

Semi-retirement (1963-68)

In 1962, Fischer said that he had "personal problems" and began to listen to various radio ministers in a search for answers. This is how he first came to listen to The World Tomorrow radio program with Herbert W. Armstrong and his son Garner Ted Armstrong; the Armstrongs' denomination, The Worldwide Church of God, predicted an imminent apocalypse. In late 1963, Fischer began tithing to the church. According to Fischer, he lived a bifurcated life, with a rational chess component and an enthusiastic religious component.

Fischer decided not to participate in the Amsterdam Interzonal in 1964, thus taking himself out of the 1966 World Championship cycle. He held to this decision even when FIDE changed the format of the eight-player Candidates Tournament from a round-robin to a series of knockout matches, which eliminated the possibility of collusion. Fischer instead embarked on a cross-country tour lasting several months, where he played simultaneous exhibitions and gave lectures; the tour was very well attended and publicized. Fischer also turned down an invitation to play in the 1963 Piatigorsky Cup tournament in Los Angeles, which had a world-class field. Instead, he preferred to play at the same time in the much weaker Western Open in Bay City, Michigan, which he won, with 7.5/8. Fischer also won the 1963 New York State Championship at Poughkeepsie, another minor event, in late summer, with a perfect 7/7 (Bobby Fischer, Profile of a Prodigy, by Frank Brady (1965)).

Fischer wanted to play in the Capablanca Memorial Tournament, Havana 1965, but Americans were not allowed to travel to Cuba at that time. Fischer had traveled to Cuba to play as a youth, before Fidel Castro assumed power in 1959. Fischer was able to play by telegraph, staying in New York and playing from the Frank Marshall Chess Club. His games lasted longer because of the transmission delays and receipt of moves logistics. But Fischer tied for 2nd-4th places, with 15/21, behind former World Champion Vasily Smyslov, and defeated Smyslov in their game. Chess became a news item in the United States with this unusual achievement (Wade & O'Connell 1972:160, 209).

Fischer finished second at the 1966 Santa Monica supertournament, just behind world finalist Boris Spassky, scoring 11/18. The next year, he won over strong fields at Monte Carlo 1967 (7/9) and Skopje 1967 (13.5/17) (http://www.chessmetrics.com, the Bobby Fischer player file).

In the next cycle, at the 1967 Sousse Interzonal, Fischer scored a phenomenal 8.5 points in the first 10 games. His observance of the Worldwide Church of God's sabbath was honored by the organizers, but deprived Fischer of several rest days, which led to a scheduling dispute. Fischer forfeited two games in protest and later withdrew, eliminating himself from the 1969 World Championship cycle.

At home, Fischer won all eight U.S. Championships that he competed in, beginning with the 1957-1958 championship and ending with the 1966-1967 championship. This string includes his 11-0 win in the 1963-1964 championship, the only perfect score in the history of the tournament, and one of only a handful of perfect scores in high-level chess tournaments ever.

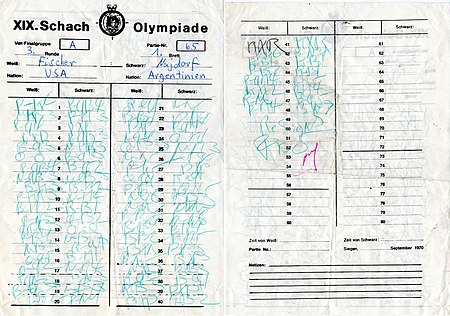

Fischer was forced to attend school, and had to miss the 1958 Olympiad. But he represented the U.S.A. on top board with great distinction at four Olympiads: (Leipzig 1960, Varna 1962, Havana 1966, and Siegen 1970). At Leipzig, he scored 13/18 for the silver medal, and the U.S.A. also won the team silver. At Varna, he scored 11/17 and the U.S.A. finished fourth. At Havana, he scored an incredible 15/17 for the individual silver, and the Americans again won team silver. Then at Siegen he again won silver with 10/13, and the U.S.A. finished fourth. His overall total was +40, =18, −7, for 49/65 or 75.4 per cent. Fischer turned down further invitations to play in 1964, 1968, and 1972, after which he retired for 20 years.

Fischer won the tournaments at Netanya 1968 (11.5/13) and Vinkovci 1968 (11/13) by large margins (http://www.chessmetrics.com, the Bobby Fischer player file). But he then stopped playing for the next 18 months, except for an amazing win in a New York Metropolitan League team match over Anthony Saidy.

The road to the world championship (1969-1972)

The 1969 U.S. Championship was also a zonal qualifier, with the top three finishers advancing to the Interzonal. Fischer, however, had sat out the U.S. Championship because of disagreements about the tournament's format and prize fund. To enable Fischer to compete for the title, Grandmaster Pal Benko gave up his Interzonal place, for which the United States Chess Federation (USCF) paid him a modest $2,000; the other zonal participants waived their right to replace Benko. This unusual arrangement was the work of Ed Edmondson, then the USCF's Executive Director.

Before the Interzonal, though, in March and April 1970, the world's best players competed in the USSR vs. Rest of the World match in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Fischer agreed to allow Bent Larsen of Denmark to play first board for the Rest of the World team in light of Larsen's recent outstanding tournament results, even though Fischer had the higher Elo rating.[18] The USSR team won the match by a hair (20.5-19.5), but on second board, Fischer beat Tigran Petrosian, whom Boris Spassky had dethroned as world champion the previous year, 3-1, winning the first two games and drawing the last two.[19]

Following the Match of the Century, the unofficial World Championship of Lightning Chess (5-minute games) was held at Herceg Novi. Fischer annihilated the super-class field with 19/22, 4.5 points ahead of Tal. Later in 1970, Fischer won tournaments at Rovinj/Zagreb with 13/17, and Buenos Aires, where he crushed the field of mostly Grandmasters with 15/17. Clearly, he had taken his game to a new level.

The Interzonal was held in Palma de Mallorca in November and December 1970. Fischer won it with a remarkable 18.5-4.5 score, 3.5 points ahead of Larsen, Efim Geller, and Robert Hübner, who tied for second at 15-8.[20] Fischer finished the tournament with seven consecutive wins (one by default).

Fischer continued his domination in the 1971 Candidates matches, defeating his opponents with a lopsided series of results unparalleled in chess history. First, he crushed Mark Taimanov of the USSR at Vancouver by 6-0. A couple of months later, he repeated the shutout against Larsen at Denver, again by 6-0 (+6−0=0).[21] The latter result was particularly shocking: just a year before, Larsen had played first board for the Rest of the World team ahead of Fischer, and had handed Fischer his only loss at the Interzonal.

Only former World Champion Petrosian, Fischer's final opponent in the Candidates matches, was able to offer resistance in their match played at Buenos Aires. Petrosian unleashed a strong theoretical novelty in the first game and had Fischer on the ropes, but Fischer defended with his customary aplomb and even won the game. This gave Fischer a remarkable streak of 20 consecutive wins, the second longest winning streak in chess history after Steinitz's 25-game streak from 1873 to 1882.[22] Petrosian won decisively in the second game, finally snapping Fischer's winning streak. After three consecutive draws, however, Fischer swept the next four games to win the match 6.5-2.5 (+5=3−1). The final match victory allowed Fischer to challenge World Champion Boris Spassky, whom he had never beaten before (+0=2−3).

1972 World Championship Match

Fischer's career-long stubbornness about match and tournament conditions was again seen in the run-up to his match with Spassky. Of the possible sites, Fischer preferred Yugoslavia, while Spassky wanted Iceland. For a time it appeared that the dispute would be resolved by splitting the match between the two locations, but that arrangement fell through. After that issue was resolved, Fischer refused to play unless the prize fund, which he considered inadequate, was doubled. London financier Jim Slater responded by donating an additional $US 125,000, which brought the prize fund to an unprecedented $250,000. Fischer finally agreed to play.

The match took place in Reykjavík, Iceland, from July through September 1972. Fischer lost the first two games in strange fashion: the first when he played a risky pawn-grab in a dead-drawn endgame, the second by forfeit when he refused to play the game in a dispute over playing conditions. Fischer would likely have forfeited the entire match, but Spassky, not wanting to win by default, yielded to Fischer's demands to move the next game to a back room, away from the cameras whose presence had upset Fischer. The rest of the match proceeded without serious incident. Fischer won seven of the next 19 games, losing only one and drawing eleven, to win the match 12.5-8.5 and become the 11th World Chess Champion.

World-class match play (i.e., a series of games between the same two opponents) often involves one or both players preparing one or two openings very deeply, and playing them often during the match. Preparation for such a match also usually involves analysis of those opening lines known to be played by the upcoming opponent. Fischer surprised Spassky by never repeating an opening line throughout the match, and often playing opening lines that he had never played before in his chess career. During the last half of the match, Spassky abandoned his prepared lines and attempted to outplay Fischer in lines that (hopefully) neither of them had prepared, but this also proved fruitless for the defending champion. [23]

Fischer's win was a momentous victory for the United States during the time of the Cold War: the iconoclastic American almost single-handedly defeating the mighty Soviet chess establishment that had dominated world chess for the past quarter-century.

Fischer was also the (then) highest-rated player in history according to the Elo rating system. He had a rating of 2780 after beating Spassky, which was actually a slight decline from the record 2785 rating he had achieved after routing Taimanov, Larsen, and Petrosian the previous year.

The match was coined "The Match of the Century", and received front-page media coverage in the United States and around the world. With his victory, Fischer became an instant celebrity. He received numerous product endorsement offers (all of which he declined) and appeared on the covers of Life and Sports Illustrated. With American Olympic swimming champion Mark Spitz, he also appeared on a Bob Hope TV special.[24] Membership in the United States Chess Federation doubled in 1972[25] and peaked in 1974; in American chess, these years are commonly referred to as the "Fischer Boom."

Fischer gave the Worldwide Church of God $61,200 of his world championship prize money. However, 1972 was a disastrous year for the church, as prophecies by Herbert W. Armstrong were unfulfilled, and the church was rocked by revelations of a series of sex scandals involving Garner Ted Armstrong.[26] Fischer, who felt betrayed and swindled by the Worldwide Church of God, left the church and publicly denounced it.

Fischer-Karpov 1975

Fischer was scheduled to defend his title against challenger Anatoly Karpov in 1975. Fischer had played no tournament games since winning the title, and he laid down numerous (a total of 64) conditions for the match. While most of them were purely game-oriented in nature, some were as bizarre as a requirement for everyone entering the room where the game is conducted to take off head covering. Many commentators supposed that Fischer's objective in making the demands was to avoid having to play the match, the outcome of which Fischer was not certain. Fischer made the following three principal demands:

- The match should continue until ten wins, without counting the draws.

- There is no limit to the total number of games played.

- In case of a 9:9 score, champion (Fischer) retains his title.

Fischer claimed the usual system (twenty-four games with the first player to get 12.5 points winning, or the champion retaining his title in the event of a 12-12 tie) encouraged the player in the lead to draw games, which he regarded as bad for chess. Fischer instead wanted a match of an unlimited number of games. However, a match based on the first two conditions could take several months (In 1927 the Capablanca-Alekhine match to achieve the condition of winning only six games continued for 34 games). Many argued that this would be an exercise in stamina rather than skill. The FIDE commission headed by FIDE president Max Euwe and consisting of both, US and USSR, representatives, ruled that the match should continue until six wins. However, Fischer replied that he would resign his crown and not participate in the match. Instead of accepting Fischer's forfeit, the commission agreed to allow the match to continue until nine wins, leaving only one of the 64 conditions set by Fischer unsatisfied. FIDE postulated that the player achieving nine victories first would win the match, eliminating any advantage for the reigning champion (Fischer). Most observers considered Fischer's demand of his win in case of 9:9 draw to be unfair. It meant that Fischer only needed to win nine games to retain the championship, while Karpov had to win by a 10-8 score. Because FIDE would not agree to that demand, Fischer resigned in a cable to FIDE president Max Euwe on June 27, 1974:

- "As I made clear in my telegram to the FIDE delegates, the match conditions I proposed were non-negotiable. Mr. Cramer informs me that the rules of the winner being the first player to win ten games, draws not counting, unlimited number of games and if nine wins to nine match is drawn with champion regaining title and prize fund split equally were rejected by the FIDE delegates. By so doing FIDE has decided against my participating in the 1975 world chess championship. I therefore resign my FIDE world chess champion title. Sincerely, Bobby Fischer."

Former U.S. Champion Arnold Denker, who was in contact with Fischer during the Karpov match negotiations, claimed that Fischer wanted a long match to be able to play himself into shape after a three-year layoff. [27] Karpov became World Champion by default in April 1975. In his 1991 autobiography, Karpov expressed profound regret that the match did not take place, and claimed that the lost opportunity to challenge Fischer held back his own chess development. Karpov met with Fischer several times after 1975, in friendly but ultimately unsuccessful attempts to arrange a match. [28] Garry Kasparov has argued that Karpov would have had a good chance to defeat Fischer in 1975. [29]

Fischer disappeared and did not play competitive chess for nearly twenty years. To this day, he claims that he is still the World Champion because he never lost a title match.

Disappearance and aftermath (1975 to present)

1975-1991

In 1982, Fischer published the pamphlet, "I Was Tortured in the Pasadena Jailhouse!", detailing his experiences following his arrest in 1981 after being mistaken for a wanted bank robber. Fischer alleged that the police treated him brutally. He was eventually charged with damaging prison property (a mattress).

The 14-page pamphlet ends with the signature: "Robert D. James (professionally known as Robert J. Fischer or Bobby Fischer, The World Chess Champion)." By this time Fischer had a Nevada driver's license and Social Security card with that name, the same one that appeared in the 1981 Pasadena police report.[30][31]

In the early 1980s, Fischer stayed for extended periods in the San Francisco-area home of his friend, the Canadian Grandmaster Peter Biyiasas. During a stretch of four months, the two played 17 five-minute games, and Fischer, despite his layoff from competitive play, won all of them, according to Biyiasas.

In 1984, Fischer wrote to the editors of the Encyclopedia Judaica, stating that he was not, and had never been, Jewish, and asking that his name be removed from the publication.[32] Encyclopedia Judaica complied with the request. [33]

Fischer arranged a financial settlement through FIDE with the Soviet Chess Federation, over the issue of many thousands of unauthorized photocopied versions of his book My 60 Memorable Games being distributed in the Soviet Union by the Soviet Federation.

1992 Spassky match

After twenty years, Fischer emerged from isolation to challenge Spassky (then placed 96-102 on the rating list) to a "Revenge Match of the 20th Century" in 1992. This match took place in Sveti Stefan and Belgrade, FR Yugoslavia, in spite of a severe United Nations embargo that included sanctions on sporting events. Fischer demanded that the organizers bill the match as "The World Chess Championship", although Garry Kasparov was the recognized FIDE World Champion. The purse for this match was reported to be $US 5,000,000 with two-thirds to go to the winner. The U.S. Department of the Treasury had warned Fischer beforehand that his participation was illegal.[34] In front of the international press, Fischer was filmed spitting on the U.S. order forbidding him to play. Following the match, the department obtained an arrest warrant for him although some dispute the legality of the Department's claim and question why others who broke the embargo have not been prosecuted.[35] Fischer won the match, 10 wins to 5, with 15 draws. Many grandmasters observing the match[who?] said that Fischer was past his prime. In the book Mortal Games, Garry Kasparov is quoted: "He is playing OK. Around 2600 or 2650. It wouldn't be close between us." He has not played any competitive games since.

Fischer insisted he was still the true world chess champion, and that all the games in the FIDE-sanctioned World Championship matches, involving Karpov, Korchnoi and Kasparov, had been pre-arranged.

Radio interviews

Fischer, whose mother and probable biological father were both Jewish[36][37], made occasional hostile comments toward Jews from at least the early 1960s. From the 1980s, however, his hatred for Jews was a major theme of his public remarks. He denied the "Holocaust of the Jews," announced his desire to make "expos[ing] the Jews for the criminals they are [...] the murderers they are" his lifework, and argued that the United States is "a farce controlled by dirty, hook-nosed, circumcised Jew bastards." [38]

In 1999, he gave a call-in interview to a radio station in Budapest, Hungary, during which he described himself as the "victim of an international Jewish conspiracy." Fischer's sudden re-emergence was apparently triggered when some of his belongings, which had been stored in a Pasadena, California storage unit, were sold by the landlord, who claimed it was in response to nonpayment of rent. Fischer interpreted this as further evidence of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy perpetrated by "the Jew-controlled U.S. Government" to defame and destroy him.[39] In 2005, some of Fischer's belongings were auctioned on eBay. In 2006, Fischer claimed that his belongings in the storage unit were worth millions.[40]

Fischer participated in at least 33 such broadcasts between 1999 and 2005, mostly with radio stations in the Philippines, but also with stations in Iceland, Colombia, and Russia.

For some years Fischer lived in Budapest, where he lived with the Jewish Polgár family. He played Chess960 blitz games as well as analyzed many games with Zsuzsa Polgar.

Radio interview after the September 11, 2001, attacks

Hours after the September 11, 2001, attacks Fischer was interviewed live[41] by Pablo Mercado on the Baguio City station of the Bombo Radyo network, shortly after midnight September 12, 2001 Philippines local time (or shortly after noon on September 11, 2001, New York time). Fischer commented on U.S and Israeli foreign policy that "nobody cares ... [that] the US and Israel have been slaughtering the Palestinians for years".[42] [43] Informed that "the White House and Pentagon have been attacked", he proclaimed "This is all wonderful news."[42][43] Fischer stated "What goes around comes around even for the United States"[42][43] and said that if the U.S. fails to change its foreign policy, it "has to be destroyed." After calling for President Bush's death, Fischer also stated he hoped that a Seven Days in May-type military coup d' etat would take over power in the U.S. and then execute "hundreds of thousands of American Jewish leaders", "arrest all the Jews" and "close all synagogues".

Subsequent to that interview, Fischer's "right to membership in the United States Chess Federation [was] canceled" by a unanimous 7-0 decision of the USCF Executive Board, taken on October 28, 2001. In 2006, that decision was subsequently "vacated" by the same Board.

Detention in 2004 and 2005

Fischer was arrested at Narita International Airport in Narita, Japan, near Tokyo for allegedly using a revoked U.S. passport while trying to board a Japan Airlines flight to Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila, Philippines. Fischer used a revoked passport that the United States Embassy in Bern, Switzerland, issued to him in 1997. The passport was revoked in 2003, although Fischer asserts that it was valid[44] and that he never received any notification that it had been canceled. Like most passports, U.S. Passports are property of the issuing government, and can be revoked without notification.

Fischer has been wanted by the United States government ostensibly for playing chess with Spassky in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1992. The match violated President George H. W. Bush's Executive Order 12810 [45] that implemented United Nations sanctions against engaging in economic activities in Yugoslavia. Fischer's supporters have stated that other U.S. citizens were present at the match, specifically reporters, and were not prosecuted. They also have stated that although Japan and the United States have a mutually binding extradition treaty, Fischer should not have been deported, as violating a U.S. executive order is not a violation of Japanese law. Tokyo-based Canadian journalist and consultant John Bosnitch set up the "Committee to Free Bobby Fischer" after meeting Fischer at Narita airport and offering to assist him. Bosnitch was subsequently allowed to participate as a friend of the court by an Immigration Bureau panel handling Fischer's case. He then worked to block the Japanese Immigration Bureau's efforts to deport Fischer to the United States and coordinated the legal and public relations campaign to free Fischer until his eventual release.

According to the Agence France-Presse, Fischer renounced his United States citizenship. A month later, it was reported that Fischer was marrying Miyoko Watai, the President of the Japanese Chess Association, with whom he had been living since 2000. Fischer also appealed to United States Secretary of State Colin Powell to help him renounce his citizenship. Under pressure from the United States, Japan's Justice Minister rejected Fischer's appeal that he be allowed to remain in the country and ordered him deported.

Political asylum in Iceland

Seeking ways to evade deportation to the United States, Fischer wrote a letter to the government of Iceland in early January 2005 and asked for an Icelandic citizenship. He also unsuccessfully requested German citizenship on the grounds that his late father, Hans Gerhardt Fischer, had been a lifelong German citizen. Sympathetic to Fischer's plight, but reluctant to grant him the full benefits of citizenship, Icelandic authorities granted him an alien's passport. When this proved insufficient for the Japanese authorities, the Althing agreed unanimously to grant Fischer full citizenship in late March for humanitarian reasons, as they felt he was being unjustly treated by the U.S. and Japanese governments.[46] Meanwhile, the U.S. government filed charges of tax evasion against Fischer in an effort to prevent him from traveling to Iceland.

When Japanese authorities received confirmation of Fischer's new citizenship, they agreed to release him and allow him to fly to Iceland. Although Iceland has an extradition treaty with the United States, Icelandic law does not permit its own citizens to be extradited. Icelandic officials reiterated their belief that the United States government had singled Fischer out for his political statements.

Shortly before his departure to Iceland on March 23, 2005, Fischer and Bosnitch appeared briefly on the BBC World Service, via a telephone link to the Tokyo airport. Bosnitch stated that Fischer would never play traditional chess again. Fischer denounced President Bush as a criminal and Japan as a puppet of the United States. He also stated that he would appeal his case to the U.S. Supreme Court and said that he would not return to the US while Bush was in power. Upon his arrival in Reykjavík, Fischer was welcomed by a crowd.

In May 2005, a delegation, including Boris Spassky, visited Iceland with the intent of "drawing Fischer back to the chessboard." Fischer appeared interested in playing a Chess960 match against a "worthy opponent." Spassky said that he was not planning to play Fischer.[47]

In 2006, Ed Trice attempted to set up a Gothic Chess match between Fischer and Anatoly Karpov.[48]

On December 10, 2006, Fischer phoned in to an Icelandic television station and pointed out a clever winning combination which was missed in a chess game which was televised in Iceland.[49]

In November 2007 some Spanish language newspapers reported that Fischer was hospitalized in Reykjavik, Iceland in for "serious physical problems and strong signs of paranoia". Inquiries by Mig Greengard confirmed that Fischer was hospitalized, but all other details were impossible to verify.[50]

Contributions to chess theory

Fischer was renowned for his opening preparation, and made numerous contributions to chess opening theory. He was considered the greatest practitioner of the White side of the Ruy Lopez; a line of the Exchange Variation (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Bxc6 dxc6 5.0-0) is sometimes called the "Fischer variation" after he successfully resurrected it at the 1966 Havana Olympiad.

He was also a recognized expert in the Black side of the Najdorf Sicilian, as well as being one of the greatest theoreticians of the King's Indian Defense. He also demonstrated several important improvements in the Grünfeld Defence. In the Nimzo-Indian Defence, the line beginning with 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e3 b6 5.Ne2 Ba6 is named for him.

Fischer established the viability of the so-called "Poisoned Pawn" variation of the Najdorf Sicilian (1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Bg5 e6 7. f4 Qb6). Although this bold queen sortie, snatching a pawn at the expense of development, had been considered dubious, Fischer succeeded in proving its soundness, a claim supported by contemporary theory. Fischer won many games with this line; his only loss was in the 11th game of his 1972 match with Spassky.

On the White side of the Sicilian, Fischer made advancements to the theory of the line beginning 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 (or e6) 6. Bc4, which is now called the Fischer-Sozin Attack.

In 1960, prompted by a painful loss to Spassky,[1] Fischer wrote an article entitled "A Bust to the King's Gambit" for the first issue of Larry Evans' American Chess Quarterly, in which he recommended 1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 d6. This variation has since become known as the Fischer Defense to the King's Gambit. After Fischer's article was published, the King's Gambit was seen even less frequently in master-level games, although Fischer took up the White side of it in three games (preferring 3.Bc4 to 3.Nf3), winning them all.

Fischer in the endgame

International Master Jeremy Silman listed Fischer as one of the five best endgame players. The others he listed were Emanuel Lasker, Akiba Rubinstein, José Capablanca, and Vasily Smyslov. Silman called him a "master of bishop endings" (Silman 2007:510–23).

The endgame of a rook and bishop versus a rook and knight (both sides with pawns) has sometimes been called the "Fischer Endgame" because of three instructive wins by Fischer in 1970 and 1971 (Müller & Lamprecht 2001:304). In all three of the games Fischer had the bishop and Mark Taimanov had the knight. One of the games was in the 1970 Interzonal and the other two were in their 1971 quarter-final candidates match in the World Championship process. Steve Mayer calls this ending the Grindable Ending, but notes that is has been sometimes called the "Fischer Ending" (Mayer 1997:201).

Other contributions to chess

Fischer clock

In 1988, Fischer filed for U.S. patent 4,884,255 for a new type of digital chess clock. Fischer's clock gave each player a fixed period of time at the start of the game and then added a small increment after each completed move. The Fischer clock soon became standard in most major chess tournaments. The patent expired in November 2001 because of overdue maintenance fees.

Fischer Random Chess

On June 19, 1996, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Fischer announced and advocated a variant of chess called Fischer Random Chess, also known as Chess960, that is intended to allow players to contest games based on their understanding of chess rather than their ability to memorize opening variations. Chess960 has gone on to be moderately popular.

- Audio clip of Bobby Fischer describing the unsavory side of chess in its current form at the highest levels.

Other talents

Fischer is an expert at solving the Fifteen puzzle, and has been timed multiple times in under 25 seconds. Fischer demonstrated this on November 8, 1972 on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Fischer was also an expert at playing pinball machines[citation needed].

In popular culture

This article may contain minor, trivial or unrelated fictional references. |

- Law & Order: Criminal Intent used his story as inspiration for the 2004-05 episode "Gone".

- Despite not narrating his life but the one of Joshua Waitzkin, the film Searching for Bobby Fischer uses his name in the title (it was named Innocent moves instead in Great Britain). In one way, the title refers to the search for Fischer's successor after his disappearance from competitive chess; in the book on which the film is based, the narrator/author actually looks for Fischer for a brief period and imagines what he would say to him if found.

- In the musical Chess, the character known variously as "The American" and in the American version of the show, as "Freddy", is based on Bobby Fischer. The seventh song of the second act, Endgame, lists his name (along with the other modern era world champions through 1980).

- Bobby Fischer's name is also used in the Saturday Night Live sketch with The Spartan Cheerleaders, played by Cheri Oteri and Will Ferrell.

Writings

- My 60 Memorable Games by Bobby Fischer (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1969, and Faber and Faber, London, 1969). This book is considered a classic text by most chess masters.

- Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess by Bobby Fischer, Donn Mosenfelder, Stuart Margulies (Bantam Books, May 1972, ISBN 0-553-26315-3). Uses programmed learning (aka programmed instruction) to help beginners learn how to see very simple chess combinations. This book is widely used by chess instructors.

- Bobby Fischer's Games of Chess by Bobby Fischer (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1959). An early collection of 34 lightly-annotated games including the famous "Game of the Century" vs. Donald Byrne.

- Checkmate by Bobby Fischer, from 1966 to 1969 in Boys' Life.

See also

Citations

- ^ Former World Champion Max Euwe, on page ix of his book Bobby Fischer--The Greatest? (Sterling Publishing Co. 1979), wrote, "One often hears the question: 'Is Fischer the best player of all time?'" Grandmaster Andrew Soltis, on page 9 of his book "Bobby Fischer Rediscovered" (Batsford 2003) called Fischer "perhaps the greatest player in history." Grandmaster Edmar Mednis, on page xiii of his book How to Beat Bobby Fischer (Dover 1997), wrote that "Fischer is a great chess champion, perhaps the greatest the world has seen . . . ." Former World Champion Garry Kasparov, on page 490 of Volume IV of My Great Predecessors (Everyman Chess 2004), wrote, "Many consider Robert Fischer to be the best chessplayer of the 20th century. Possibly this is so." Golombek's Encyclopedia of Chess (Crown Publishers, 1977) at page 117 says Fischer is "for many, the greatest player of all time." The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia (Batsford 1990) at page 67 calls him "one of the very greatest players of all time."

- ^ Bobby Fischer interviewed by Pablo Mercado, Radio Bomba, September 12, 2001, accessed September 2 2006

- ^ FBI watched chess genius and family. Fischer's mother suspected as spy November 18, 2002

- ^ Schach Nachrichten in German

- ^ Nicholas, Peter, and Clea Benson, Files reveal how FBI hounded chess king November 17, 2002, accessed February 17, 2005 via archive.org

- ^ Bobby Fischer

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p. 100

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p.101)

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p.105)

- ^ Vinay Bhat...Cal Chess Hall of Fame September 28 2002

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p.127

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p.130

- ^ http://www.chessmetrics.com, the Bobby Fischer player file

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p.347

- ^ By 2005, twice as many candidates were being selected from this tournament. Thus Magnus Carlsen took one of 16 available places, while Fischer took one of 8. Carlsen was a year younger (14 years) at the time

- ^ The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert Wade and Kevin O'Connell, Batsford 1972, p.356

- ^ USSR vs Rest of the World: Belgrade 1970 "The Match of the Century"

- ^ USSR vs the Rest of the World (1970)

- ^ World Chess Championship, 1970 Palma de Mallorca Interzonal Tournament

- ^ The Greatest Chess Player of All Time – Part II April 28, 2005

- ^ Chess Records

- ^ _Fischer vs. Spassky, The Chess Match of the Century_, by Svetozar Gligoric, (c) 1972 by The Chess Player

- ^ Bob Hope's Comedy Collection 1972

- ^ About the USCF

- ^ In Bed With Garner Ted

- ^ Arnold Denker & Larry Parr, The Bobby Fischer I Knew And Other Stories (Hypermodern Press 1995)

- ^ Anatoly Karpov, Karpov on Karpov: Memoirs of a Chess World Champion (Atheneum 1991).

- ^ Garry Kasparov, My Great Predecessors. Vol. 5.

- ^ Bobby Fischer’s Pathetic Endgame December 2002

- ^ Bobby Fischer's Pathetic Endgame (backup copy)

- ^ An Open Letter from Fischer to Encyclopedia Judaica June 28, 1984

- ^ Reply to Bobby Fischer from Encyclopedia Judaica, September 24, 1984

- ^ Threatening Letter to Bobby Fischer

- ^ Why would I want to reinstate Fischer?

- ^ Ginzburg, Ralph, Portrait of a Genius As a Young Chess Master, Harper's Magazine, January 1962, accessed October 4, 2007 via bobby-fischer.net

- ^ Nicholas, Peter, and Clea Benson Life is not a Board Game, The Philadelphia Inquirer February 8, 2003 accessed October 4, 2007 via bobby-fischer.net

- ^ Parr, Larry: "Is Bobby Fischer Anti-Semitic?", Chess News, (May 2001)

- ^ Bobby Fischer Live Interview

- ^ Fischer on Icelandic Radio April 11, 2006

- ^ Bobby Fischer interviewed by Pablo Mercado, Radio Bomba, September 12, 2001, accessed September 2, 2006

- ^ a b c Bamber, David (December 2, 2001). "Bobby Fischer speaks out to applaud Trade Centre attacks". Sunday Telegraph (London). p. 17.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "The Bin Laden defense; Diatribe; Bobby Fischer speaks out in favor of 9/11 attacks; Brief Article; Transcript". Harper's Magazine. 304 (1822): 27. March 1, 2002. 0017-789X.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Embassy of the United States of America - US Passport Revoked December 11, 2003

- ^ George Bush: Executive Order 12810 - Blocking Property of and Prohibiting Transactions With the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro)June 5, 1992

- ^ Bobby Fischer: ich bin ein Icelander! March 21, 2005

- ^ Breaking news: Fischer comeback? May 27, 2005

- ^ SOLTIS, ANDY (2006-10-29). "BOBBY, TOLYA MAY BE GAME FOR GOTHIC". The New York Post. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ Bobby Fischer and the missed combination December 17, 2006

- ^ http://www.chessninja.com/dailydirt/2007/11/fischer_hospitalized_in_reykjavik.htm

References

- Mayer, Steve (1997), Bishop versus Knight: The Verdict, Batsford, ISBN 1-879479-73-7

- Müller, Karsten; Lamprecht, Frank (2001), Fundamental Chess Endings, Gambit Publications, ISBN 1-901983-53-6

- Silman, Jeremy (2007), Silman's Complete Endgame Course: From Beginner to Master, Siles Press, ISBN 1-890085-10-3

- Wade, Robert; O'Connell, Kevin (1972), The Games of Robert J. Fischer, Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-2099-5

Further reading

- Bobby Fischer: A Study of His Approach to Chess by Elie Agur, Cadogan; 1992, ISBN 1-85744-001-3.

- Bobby Fischer Goes to War by David Edmonds and John Eidinow, Faber and Faber 2004, ISBN 0-571-21411-8.

- Bobby Fischer, Profile of a Prodigy by Frank Brady, McKay 1973. Fischer, in one of his radio interviews, said this book was "full of lies."

- Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach, Stein & Day, 1974.

- Bobby Fischer - wie er wirklich ist: Ein Jahr mit dem Schachgenie by Petra Dautov, ISBN 3-9804281-3-3.

- How to Beat Bobby Fischer by Edmar Mednis, Dover; 1998, ISBN 0-486-29844-2. This expanded edition includes Fischer's losses from the second match with Spassky.

- My Great Predecessors, Part IV: On Fischer by Garry Kasparov, London 2004, ISBN 978-1-85744-395-0.

- Russians Vs. Fischer, second edition, ed. Dmitry Plisetsky and Sergey Voronkov, Everyman, 2005, ISBN 1-85744-380-2.

- World Champion Fischer (Chessbase, CD-ROM) - includes all Fischer's games (around half annotated), biographical notes, and an examination by Robert Hübner of Fischer's annotations in My Sixty Memorable Games.

- World Chess Champions by Edward G. Winter, editor, 1981, ISBN 0-08-024094-1.

- Bobby Fischer Rediscovered, by Andrew Soltis, 2003, Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-8846-8.

- The Unknown Bobby Fischer, by John Donaldson and Eric Tangborn, International Chess Enterprises, ISBN 1-879479-85-0.

- The Games of Robert J. Fischer, edited by Robert G. Wade and Kevin J. O'Connell, Batsford, 1972, ISBN 0-7134-2099-5.

- The Bobby Fischer I Knew And Other Stories, by Arnold Denker and Larry Parr, Hypermodern Press 1995, ISBN 1-886040-18-4.

External links

- Official Site - Contains statements and radio interviews

- "Portrait of a Genius As a Young Chess Master". Ralph Ginzburg's 1962 interview.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Bobby Fischer: Demise of a chess legend, the BBC on Fischer's personality and downfall

- Fischer Watch Index of Fischer news stories

- Ambassador Report Fischer's involvement with Armstrong

- FIDE

- Chessgames

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from September 2007

- 1943 births

- Living people

- World chess champions

- Chess grandmasters

- American chess players

- American chess writers

- American expatriates

- American Jews

- Antisemitism

- Icelandic Jews

- Jewish chess players

- Refugees

- People from Brooklyn

- People from New York City

- People from Chicago

- Holocaust deniers