Bonyad

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Iran |

|---|

|

| History of Islam in Iran |

| Scholars |

| Sects |

| Culture |

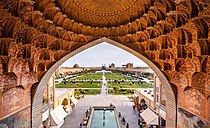

| Architecture |

| Organizations |

|

|

Bonyads (Persian: بنیاد "Foundation") are charitable trusts in Iran that play a major role in Iran's non-petroleum economy, controlling an estimated 20% of Iran's GDP,[1] and channeling revenues to groups supporting the Islamic Republic.[2] Exempt from taxes, they have been called "bloated",[3] and "a major weakness of Iran’s economy",[4] and criticized for reaping "huge subsidies from government", while siphoning off production to the lucrative black market and providing limited and inadequate charity to the poor.[3]

Background

Monarchy

Founded as royal foundations by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the original bonyads were criticized for providing a "smokescreen of charity" to patronage, economic control, for-profit wheeling and dealing done with the goal of "keep[ing] the Shah in Power."[5] Resembling more a secretive conglomerate than a charitable trust, these bonyads invested heavily in property development, such as the Kish Island resort; but the developments' housing and retail was oriented to the middle and upper classes, rather than the poor and needy.[6]

Islamic Republic

After the 1979 Iranian revolution, the Bonyads were nationalized and renamed with the declared intention of redistributing income to the poor and families of martyrs, i.e. those killed in the service of the country. The assets of many Iranians whose ideas or social positions ran contrary to the new Islamic government were also confiscated and given to the Bonyads without any compensation.

Today, there are over 100 Bonyads,[7] and they are criticized for many of the same reasons as their predecessors. They form tax-exempt, government subsidized, consortiums receiving religious donations and answerable directly (and only) to the Supreme Leader of Iran. The Bonyads are involved in everything from vast soybean and cotton fields to hotels to soft drinks to auto-manufacturing to shipping lines. The most prominent, the Bonyad-e Mostazafen va Janbazan, (Foundation for the Oppressed and Disabled), for example, "controls 20% of the country's production of textiles, 40% of soft drinks, two-thirds of all glass products and a dominant share also in tiles, chemicals, tires, foodstuffs."[8] Some economists argue that its chair, and not the Minister of Finance or president of the Central bank, is considered the most powerful economic post in Iran.[9] In addition to the very large national Bonyads, "almost every Iranian town has its own bonyad", affiliated with local mullahs.[10]

Estimates of how many people the bonyads employ ranges from in excess of 400,000[11] to "as many as 5 million".[4]

Bonyads also play a crucial role in the spread of Iranian influence through extensive transnational and international activities, including philanthropy and commerce as soft power as well as providing hard power support.[12]

Criticism

Bonyads are criticized as enormously wasteful: overstaffed,[13] corrupt, and generally unprofitable. In 1999 Mohammad Forouzandeh, a former defense minister, reported that 80% of Iran's Bonyad companies were losing money.[13]

Bonyad companies also compete with Iran's unprotected private sector, whose firms complain of the difficulty of competing with bonyad firms whose political connections provide government permits and subsidies which eliminate worries over the need to make a profit in many market sectors. These Bonyads, by their very presence, hamper healthy economic competition, efficient use of capital and other resources, and growth.[7]

Unification of Iran's social security system

As charity organizations they are supposed to provide social services to the poor and the needy; however, "since there are over 100 of these organisations operating independently, the government doesn't know what, why, how and to whom this help and assistance is given." Bonyads do not fall under Iran’s General Accounting Law and, consequently, are not subject to financial audits.[14] Unaccountable to the Central Bank governor, the bonyads "jealously guard their books from prying eyes."[15] Lack of proper oversight and control of these foundations has also hampered the government's efforts in creating a comprehensive, central and unified social security system in the country, undertaken since 2003.[7][16] Iran has 12 million people living below the poverty line, six million of whom are not supported by any foundation or organization.[17]

So as to clearly distinguish its activities from the formal Social Security Organization (SSO), bonyads would have to be in charge of vocational training centers, rehabilitation centers, socioeconomic centers, all drug-related rehabilitation centers, cooperative banking (while financing these activities with the bonyads large commercial holdings, which then could be privatized). The SSO, on the other hand, could have sole responsibility for unemployment-insurance, professional-rehabilitation/training costs, retirement-pensions, disability funds, etc.[citation needed]

Rather than charitable organizations, the bonyads have been described as "patronage-oriented holding companies that ensure the channeling of revenues to groups and milieus supporting the regime," but don't help the poor as a class.[2] Another complaint describes them as having kept to their charitable mission for the first decade of the Islamic Republic, but having "increasingly forsaken their social welfare functions for straightforward commercial activities" since the death of Imam Khomeini.[10] Local city and town bonyad have been accused of sometimes using extortionate techniques to draw the traditional Shia Islamic 20% khums donations from local business owners.[10]

Seized assets

In certain well known instances, such as the confiscation of the properties and assets of the Boroumand family of Esfahan, the Islamic Revolutionary Court judge responsible for unjustly ordering the seizure and confiscation of that family's belongings was identified as a criminal, who was subsequently executed by the Islamic regime on charges of "corruption on earth", yet his confiscation ruling was let to stand.[citation needed]

In the rare instances where courts have ordered the Bonyad Mostazafan to return the properties of individuals whose belongings were unjustly seized, the Bonyad Mostazafan has refused to do so, instead offering to remunerate those individuals at the prices prevalent at the time at which those assets were seized in 1979, effectively denying the legitimate owners over 30 years of lost income and compensating them at only a tiny fraction of the true value of their belongings.[citation needed]

List of major bonyads

- Mostazafen Foundation of Islamic Revolution, one of the largest welfare organization, A semi-public foundation founded in 1979 with the assets of the last Shah's family; it operates a wide variety of charitable activities. With a reported $10 billion in assets (2003).[18]

- Astan Quds Razavi (Imam Reza shrine Foundation), with $15 billion in assets (2003).[18]

- NAJA Cooperation Bonyad

- IRGC Cooperation Bonyad

- Bonyad Shahid va Omur-e Janbazan (Foundation of Martyrs and Veteran Affairs), one of the biggest with over 100 companies. Provides welfare assistance to families of the Martyrs of the Iran–Iraq War.

- Pilgrimage Foundation

- Housing Foundation

- Imam Khomeini Relief Committee, provides sickness, maternity, and work injury benefits to some workers in the private sector.

See also

- Smuggling in Iran

- Economy of Iran

- Privatization in Iran

- List of Iranian companies

- Iranian labor law

- International rankings of Iran

- Banking in Iran

- Healthcare in Iran

- Agriculture in Iran

- Mining in Iran

- Tourism in Iran

- Transport in Iran

- Energy in Iran

- Taxation in Iran

Further reading

- Annual Review by the Central Bank of Iran, including statistics about social security in Iran.

- "A mess." The Economist, July 19, 2001.

- "Stunted and Distorted." The Economist, January 16, 2003.

- "Still fading, still defiant." The Economist, December 9, 2004.

- "Inside Iran's Holy Money Machine." Wall Street Journal, June 2, 2007. Details about the Imam Reza shrine, the largest active bonyad in Iran.

- "Bonyad-e Mostazafen va Janbazan, (Foundation for the Oppressed and Disabled)" globalsecurity.org

- World Bank Statistics Human development, social and economic indicators for Iran

- Iran's Ministry of Welfare and Social Security policies still based on charity

- Iran Para-governmental Organizations (bonyads) By Ali A. Saeidi (Source: The Middle East Institute)

- Poverty and Inequality since the Revolution By Djavad Salehi-Isfahani (Source: The Middle East Institute)

- Iran’s Bonyads: Economic Strengths and Weaknesses. Katzman, Kenneth (2006)

External links

- Imam Khomeiny Relief Foundation

- Bonyad Shahid va Isaar-Garaan (Foundation of the Martyrs and the Affairs of Self-Sacrificers)

- Bonyad Shahid va Omur-e Janbazan (Foundation of Martyrs and Veteran Affairs)

- Bonyad-e Mostazafan va Janbazan (Foundation for the Oppressed and Disabled)

- Bonyad Panzdah Khordad (Foundation of the 15 Khordad)

- Astan Quds Razavi (Imam Reza Shrine Foundation)

References

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, Soul of Iran, Norton, (2006), p.176

- ^ a b Roy, Olivier, The Failure of Political Islam by Olivier Roy, translated by Carol Volk, Harvard University Press, 1994, p.139

- ^ a b Mackey, Sandra Iranians, Persia, Islam, and the soul of a nation, New York: Dutton, c1996 (p.370)

- ^ a b Katzman, Kenneth. Iran’s Bonyads: Economic Strengths and Weaknesses. 6 Aug 2006 Archived 2008-10-25 at the Wayback Machine accessed 15-May-2009

- ^ Graham, Robert, Iran: The Illusion of Power, St. Martin's Press, 1980, p.157, 8

- ^ Graham, Iran, (1980), p.161

- ^ a b c "Ahmadinejad's Achilles Heel: The Iranian Economy" by Dr. Abbas Bakhtiar

- ^ NHH Sam 2007, Destructive Competition [permanent dead link]

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p.176

- ^ a b c Millionaire mullahs by Paul Klebnikov, July 7, 2003, The Iranian Originally printed in Forbes, accessed 15-May-2009

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Columbia University Press, 2008, p.178

- ^ Jenkins, WB, Bonyads as Agents and Vehicles of the Islamic Republic’s Soft Power in Iran in the World: President Rouhani's Foreign Policy, eds. Akbarzadeh, S. & Conduit, D., Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp.155-176

- ^ a b "Business: A mess; Iranian privatisation", The Economist. London: Jul 21, 2001. Vol. 360, Iss. 8231; pg. 51

- ^ https://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/107234.pdf

- ^ Molavi, Soul of Iran, (2005) p.176

- ^ World bank: country brief

- ^ Tehran Times - Poverty in Iran [dead link]

- ^ a b "Millionaire Mullahs". Forbes. 2003-07-21. Retrieved 2014-03-13.