Carbonate

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Carbonate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CO2− 3 | |

| Molar mass | 60.008 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

In chemistry, a carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid,[1] characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, CO2−

3. The name may also mean an ester of carbonic acid,[1] an organic compound containing the carbonate group C(=O)(O–)2.

The term is also used as a verb, to describe carbonation: the process of raising the concentrations of carbonate and bicarbonate ions in water to produce carbonated water and other carbonated beverages — either by the addition of carbon dioxide gas under pressure, or by dissolving carbonate or bicarbonate salts into the water.

In geology and mineralogy, the term "carbonate" can refer both to carbonate minerals and carbonate rock (which is made of chiefly carbonate minerals), and both are dominated by the carbonate ion, CO2−

3. Carbonate minerals are extremely varied and ubiquitous in chemically precipitated sedimentary rock. The most common are calcite or calcium carbonate, CaCO3, the chief constituent of limestone (as well as the main component of mollusc shells and coral skeletons); dolomite, a calcium-magnesium carbonate CaMg(CO3)2; and siderite, or iron(II) carbonate, FeCO3, an important iron ore. Sodium carbonate ("soda" or "natron") and potassium carbonate ("potash") have been used since antiquity for cleaning and preservation, as well as for the manufacture of glass. Carbonates are widely used in industry, e.g. in iron smelting, as a raw material for Portland cement and lime manufacture, in the composition of ceramic glazes, and more.

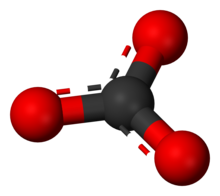

Structure and bonding

The carbonate ion is the simplest oxocarbon anion. It consists of one carbon atom surrounded by three oxygen atoms, in a trigonal planar arrangement, with D3h molecular symmetry. It has a molecular mass of 60.01 g/mol and carries a negative two formal charge. It is the conjugate base of the hydrogen carbonate (bicarbonate) ion, HCO3−

, which is the conjugate base of H2CO3, carbonic acid.

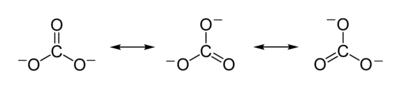

The Lewis structure of the carbonate ion has two (long) single bonds to negative oxygen atoms, and one short double bond to a neutral oxygen.

This structure is incompatible with the observed symmetry of the ion, which implies that the three bonds are equally long and that the three oxygen atoms are equivalent. As in the case of the isoelectronic nitrate ion, the symmetry can be achieved by a resonance between three structures:

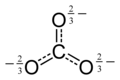

This resonance can be summarized by a model with fractional bonds and delocalized charges:

Chemical properties

Metal carbonates generally decompose on heating, liberating carbon dioxide from the long term carbon cycle to the short term carbon cycle and leaving behind an oxide of the metal.[1] This process is called calcination, after calx, the Latin name of quicklime or calcium oxide, CaO, which is obtained by roasting limestone in a lime kiln.

A carbonate salt forms when a positively charged ion, M+

, M2+

, or M3+

, attaches to the negatively charged oxygen atoms of the ion, forming an ionic compound:

- 2 M+

+ CO2−

3 → M

2CO

3

- M2+

+ CO2−

3 → MCO

3

- 2 M3+

+ 3 CO2−

3 → M

2(CO

3)

3

Most carbonate salts are insoluble in water at standard temperature and pressure, with solubility constants of less than 1 × 10−8. Exceptions include lithium, sodium, potassium and ammonium carbonates, as well as many uranium carbonates.

In aqueous solution, carbonate, bicarbonate, carbon dioxide, and carbonic acid exist together in a dynamic equilibrium. In strongly basic conditions, the carbonate ion predominates, while in weakly basic conditions, the bicarbonate ion is prevalent. In more acid conditions, aqueous carbon dioxide, CO2(aq), is the main form, which, with water, H2O, is in equilibrium with carbonic acid - the equilibrium lies strongly towards carbon dioxide. Thus sodium carbonate is basic, sodium bicarbonate is weakly basic, while carbon dioxide itself is a weak acid.

Carbonated water is formed by dissolving CO2 in water under pressure. When the partial pressure of CO2 is reduced, for example when a can of soda is opened, the equilibrium for each of the forms of carbonate (carbonate, bicarbonate, carbon dioxide, and carbonic acid) shifts until the concentration of CO2 in the solution is equal to the solubility of CO2 at that temperature and pressure. In living systems an enzyme, carbonic anhydrase, speeds the interconversion of CO2 and carbonic acid.

Although the carbonate salts of most metals are insoluble in water, the same is not true of the bicarbonate salts. In solution this equilibrium between carbonate, bicarbonate, carbon dioxide and carbonic acid changes consonant to changing temperature and pressure conditions. In the case of metal ions with insoluble carbonates, e.g. CaCO3, formation of insoluble compounds results. This is an explanation for the buildup of scale inside pipes caused by hard water.

Organic carbonates

In organic chemistry a carbonate can also refer to a functional group within a larger molecule that contains a carbon atom bound to three oxygen atoms, one of which is double bonded. These compounds are also known as organocarbonates or carbonate esters, and have the general formula ROCOOR′, or RR′CO3. Important organocarbonates include dimethyl carbonate, the cyclic compounds ethylene carbonate and propylene carbonate, and the phosgene replacement, triphosgene.

Biological significance

It works as a buffer in the blood as follows: when pH is too low, the concentration of hydrogen ions is too high, so one exhales CO2. This will cause the equation to shift left, essentially decreasing the concentration of H+ ions, causing a more basic pH.

When pH is too high, the concentration of hydrogen ions in the blood is too low, so the kidneys excrete bicarbonate (HCO−

3). This causes the equation to shift right, essentially increasing the concentration of hydrogen ions, causing a more acidic pH.

There are 3 important reversible reactions that control the above pH balance.[2]

1. H2CO3(aq) ⇌ H+(aq) + HCO−

3(aq)

2. H2CO3(aq) ⇌ CO2(aq) + H2O(l)

3. CO2(aq) ⇌ CO2(g)

Exhaled CO2(g) depletes CO2(aq) which in turn consumes H2CO3 causing the aforementioned shift left in the first reaction by Le Châtelier's principle. By the same principle when the pH is too high, the kidneys excrete bicarbonate (HCO−

3) into urine as urea via the urea cycle (a.k.a. the Krebs–Henseleit ornithine cycle). By removing the bicarbonate more H+ is generated from carbonic acid (H2CO3) which come from CO2(g) produced by cellular respiration.

Crucially this same buffer operates in the oceans. It is a major factor in climate change and the long term carbon cycle. This is due to the large number of marine organisms (especially coral) which are formed of calcium carbonate. Increased solubility of carbonate through increased temperatures results in lower production of marine calcite and increased concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide. This in turn increases Earth temperature and is a part of the carbon cycle largely ignored by the global news media. The tonnage of CO2−

3 is on a geological scale and may all be redissolved into the sea and released to the atmosphere, increasing CO2 levels even more.

Carbonate salts

- Carbonate overview:

Presence outside Earth

It is generally thought that the presence of carbonates in rock is strong evidence for the presence of liquid water. Recent observations of the planetary nebula NGC 6302 shows evidence for carbonates in space,[3] where aqueous alteration similar to that on Earth is unlikely. Other minerals have been proposed which would fit the observations.

Until recently carbonate deposits have not been found on Mars via remote sensing or in situ missions, even though Martian meteorites contain small amounts. Groundwater may have existed at both Gusev[4] and Meridiani Planum.[5]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ http://www.scifun.org/chemweek/BioBuff/BioBuffers.html

- ^ Kemper, F., Molster, F.J., Jager, C. and Waters, L.B.F.M. (2002) The mineral composition and spatial distribution of the dust ejecta of NGC 6302. Astronomy & Astrophysics 394, 679-690.

- ^ Squyres et al., (2007) doi 10.1126/science.1139045

- ^ Squyres et al., (2006) doi 10.1029/2006JE002771