Carniola

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2010) |

Carniola | |

|---|---|

Landscape of Lower Carniola in Slepšek | |

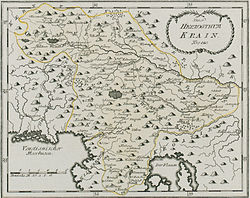

1791 map of Carniola | |

| Country | Slovenia |

| Elevation | 400 m (1,300 ft) |

Carniola (Slovene, Serbo-Croatian Latin: Kranjska;[1][2] German: Krain; Italian: Carniola; Hungarian: Krajna) was a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region still tend to identify with its traditional parts Upper Carniola, Lower Carniola (with the sub-part of White Carniola), and to a lesser degree with Inner Carniola. In 1991, 47% of the population of Slovenia lived within the borders of the former Duchy of Carniola.

|

| 1 Slovenian Littoral; Carniola: 2a Upper 2b Inner, 2c Lower 3 Carinthia; 4 Styria; 5 Prekmurje |

General

A state of the Holy Roman Empire in the Austrian Circle and a duchy in the hereditary possession of the Habsburgs, later part of the Austrian Empire and of Austria-Hungary, the region was a crown land from 1849, when it was also subdivided into Upper Carniola, Lower Carniola, and Inner Carniola, until 1918. Its capital was originally Krainburg, for a short period Stein, and from the second half of the 13th century, Laibach or Ljubljana. Nowadays, its territory (in the extent at its dissolution) is almost entirely located in Slovenia, except for a small part in the northwest Italy, around Fusine in Valromana.[3][notes 1] Carniola in its final form, established in 1815,[4] encompassed 9,904 km2 (3,824 sq mi).[5] In 1914, before the beginning of World War I, it had a population of slightly under 530,000 inhabitants.[4]

Geography

This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2015) |

The Julian and Karavanken Alps traverse the country. The highest mountain peaks are Nanos, 4,200 feet (1,300 m); Vremščica, 3,360 feet (1,020 m); Snežnik, 5,900 feet (1,800 m); and Triglav, 9,300 feet (2,800 m). The principal rivers are Sava, Tržič Bistrica, Kokra, Kamnik Bistrica, Sora, Ljubljanica, Mirna, Krka, and Kolpa, which serves as a boundary with Croatia. The principal lakes are Black Lake (Slovene: Črno jezero), spreading into seven lakes, of which the highest is over 6,000 feet (1,800 m) above sea level; Lake Bohinj; Lake Bled, in the middle of which on an island is built a church to the Blessed Virgin, amidst most picturesque scenery; Lake Cerknica, 1,700 feet (520 m) above sea level, varies annually in extent from about 5 to 10 square miles (13 to 26 km2). It was known to the Romans as Lugea palus, and is a natural curiosity. Dante Alighieri mentions it in his Divine Comedy (Inferno, xxxii). The Ljubljana Marshes cover an area of 76 square miles (200 km2). Hot and mineral springs are to be found at Sušica, Šmarjetske, and Medijske. There is an interesting cave at Postojna.

Agriculture thrives better in Upper than in Lower Carniola. The Vipava Valley is especially famous for its wine and vegetables, and for its mild climate. The principal exports are all kinds of vegetables, clover-seed, lumber, carvings, cattle, and honey. In the mineral kingdom the principal products are iron, coal, quicksilver, manganese, lead, and zinc. Upper Carniola has the most industries, among the products being lumber, linen, woollen stuffs, and lace (in Idrija), bells, straw hats, wicker-work, and tobacco. The railroads are[when?] the Juzna, the Prince Rudolf, the Bohinjska, the Kamniska, the Dolenjska, and the Vrhniska. The principal cities and towns are: Kamnik, Kranj, Tržič, Vrhnika, Vipava, Idrija (which has the richest quicksilver mine in the world), Turjak, Ribnica, Metlika, Novo Mesto, Vače (famous for its prehistoric graveyard). The mean average temperature in spring is 56 °F (13 °C); in summer, 77 °F (25 °C); in autumn, 59 °F (15 °C) and in winter, 26 °F (−3 °C).

Of the inhabitants 95 per cent were[when?] Slovenes, kinsmen to the Croats; the remainder are Germans, 700 Croats, and Italians. In the districts of Gottschee and Črnomelj dwell the people of White Carniola (Slovene: Bela Krajina) for a connecting link between the Croats and Slovenes. One-half of the Germans live in Gottschee, 5000 in Ljubljana, 3500 at Novo Mesto, and 1000 at Radovljica. The Germans at Gottschee were settled there by Otho, Count of Ortenburg, in the fourteenth century, and they preserve their Tyrolean German dialect.

History

Overview

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Lombards settled in Carniola, followed by Slavs around the 6th century AD.[6][7][8] As a part of the Holy Roman Empire, the area was successively ruled by Bavarian, Frankish and local nobility, and eventually by the Austrian Habsburgs almost continuously from 1335 to 1918, though beset by many raids from the Ottomans and rebellions by local residents against Habsburg rule from the 15th to the 17th centuries. From about 900 AD until the 20th century, Carniola's ruling classes and urban areas spoke German, while the peasantry spoke Slovene.

The capital of Carniola, originally situated at Kranj (Krainburg), was briefly moved to Kamnik (Stein) and finally to the current capital of Slovenia, Ljubljana (Laibach).

Chronology

- Sixth century – Slovene settlements.

- Eighth century – Carniola a part of the Empire of Charles the Great.

- Tenth century – Carniola a separate country.

- 1278 – Death of Ottokar II of Bohemia. Carniola absorbed in the Habsburg dominions.

- Fourteenth century – The province under Albert III.

- Fifteenth and sixteenth centuries – Ravages of the Turks.

- 1527–64 – Progress of the Reformation in Carniola.

- 1564 – Death of Ferdinand I. Carniola under the Archduke Charles. Religious persecutions begin.

- 1763 – Political administration of "Inner Austria" centralized at Graz.

- 1790 – Accession of Leopold II. Partial revival of autonomy.

- 1797 – First French invasion.

- 1805 – Second French invasion.

- 1809 – Treaty of Schönbrunn. Carniola under French rule.

- 1814 – Congress of Vienna. Carniola restored to Austria.[9]

Antiquity and Middle Ages

Before the coming of the Romans (c. 200 BC), the Taurisci dwelt in the north of Carniola, the Pannonians in the southeast, the Iapodes or Carni, a Celtic tribe, in the southwest.

Carniola formed part of the Roman province of Pannonia; the northern part was joined to Noricum, the south-western and south-eastern parts and the city of Aemona to Venice and Istria. In the time of Augustus all the region from Aemona to the Kolpa river (Culpa) belonged to the province of Savia.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476), Carniola was incorporated into Odoacer's the Kingdom of Italy, and then in 493, under Theodoric, it formed part of the Ostrogothic kingdom. Between the upper Sava and the Soča rivers lived the Carni, and towards the end of the sixth century Slavs settled the region called by Latin writers Carnia, or Carniola meaning 'little Carnia'; i.e., part of greater Carnia. The Latin name was later borrowed into Slavic, becoming Kranjska,[10] and into German as Chrainmark, Krain.

The new inhabitants, to whom modern historiography frequently refers to as Alpine Slavs, were subjected to the Avars, but around 623 they joined the Slavic tribal union of Samo. After Samo's death in 658 AD, they fell again under the Avar rule, but most probably enjoyed partial autonomy.

March of Carniola

Carniola was governed by the Franks about the year 788, and was Christianized by missionaries from the Patriarchate of Aquileia and others. When Charlemagne established the margraviate of Friuli, he added to it a part of Carniola. After the division of Friuli, it became an independent margraviate, having its own Slavic margrave residing at Kranj, subject to the governor of Bavaria at first, and after 976 to the Dukes of Carinthia. Henry IV gave it to the Patriarch of Aquileia (1071) and it formed part of the Patriarchal State of Friuli.

Several sources from the High Middle Ages suggest that there was a common Carantanian (that is, Carinthian) identity that slowly vanished after the 14th century and was replaced by a regional Carniolan identity.

In the Middle Ages the Church held much property in Carniola, thus in Upper and Lower Carniola the Bishop of Freising became in 974 a feudal lord of the city of Škofja Loka, the Bishop of Brixen held Bled and possessions in the valley of Bohinj, and the Bishop of Lavant got Mokronog.

Among secular potentates the Dukes of Meran, Gorizia (from Slovenian name Gorica), Babenberg, and Zilli held possessions given to them in fief by the patriarchs of Aquileia. The dukes governed the province nearly half a century.

Finally Carniola was given in fief with the consent of the patriarch to Frederick II of Austria, who obtained the title of duke in 1245. Frederick was succeeded by Ulrich III, Duke of Carinthia, who married Agnes of Andechs a relative of the patriarch and endowed the churches and monasteries, established the government mint at the city of Kostanjevica, and finally (1268) willed to Ottokar II, King of Bohemia, all his possessions and the government of Carinthia and Carniola.

Duchy of Carniola

Ottokar was defeated by Rudolph I of Germany, and at the meeting at Augsburg in 1282, he gave in fief to his sons Albrecht and Rudolf the province of Carniola, but it was leased to Meinhard, count of Gorizia-Tirol. Duke Henry of Carinthia claimed Carniola; and the Dukes of Austria asserted their claim as successors to the Bohemian kingdom. When Henry died 1335 Jan, King of Bohemia, renounced his claims, and Albrecht, Duke of Austria, received Carniola; it was proclaimed a duchy by Rudolf IV, in 1364. Emperor Frederick III united Upper, Lower, and Central Carniola as Metlika and Pivka into one duchy. The union of the dismembered parts was completed by 1607.

French Intermezzo

The French revolutionary troops occupied Carniola in 1797, and from 1805 to 1806. Under the Treaty of Vienna, Carniola became part of the Illyrian provinces of France (1809–1814), with Ljubljana as its capital, and Carniola formed a part of the new territory from 1809 to 1813. The defeat of Napoleon restored Carniola to Austrian Emperor Francis I, with larger boundaries, but at the extinction of the Illyrian Kingdom Carniola was confined to the limits outlined at the Congress of Vienna, 1815. From 1816 to 1849 Carniola was part of the Austrian Kingdom of Illyria with capital in Ljubljana.

Ecclesiastical history

In early Christian times the duchy was under the jurisdiction of the metropolitans of Aquileia (who became Patriarchs), Syrmium, and Salona. In consequence of the immigration of the pagan Slovenes, this arrangement was not a lasting one. After they had embraced Christianity in the seventh and eighth centuries Charlemagne conferred the major part of Carniola on the Patriarchate of Aquileia, and the remainder on the Diocese of Trieste. In 1100 that patriarchate was divided into five archdeaconries, of which Krain was one.

The diocese of Ljubljana or Laibach was established by Emperor Frederick III on 6 December 1461. It was directly subject to the pope. This was confirmed by a Bull of Pope Pius II, 10 September 1462. The new diocese consisted of part of Upper Carniola, two parishes in Lower Carniola, and a portion of Lower Styria and Carinthia; the remaining portion of Carniola was attached to Aquileia, later on to Gorizia and Trieste. At the redistribution of dioceses (1787 to 1791) not all the parishes in Carniola were included in the Diocese of Ljubljana, but this was accomplished in 1833, by taking two deaneries from the Diocese of Trieste, one from Gorizia, and one parish from the Diocese of Lavant, so as to include all the territory within the political boundaries of the crownland.

Austrian administration

The Austrian Empire reorganized the territory in 1849 as a duchy and a Cisleithanian crownland in Austria-Hungary known as the Duchy of Carniola. It was bounded on the north by Carinthia, on the north-east by Styria, on the south-east and south by Croatia, and on the west by Trieste, Goritza, and Istria; with area of 3,857 square miles (9,990 km2) and population of 510,000. The capital, Ljubljana, was the see of a prince-bishop, population, 40,000; it was known to the Romans as Aemona, and was destroyed by Obri in the sixth century. Carniola was divided into Upper Carniola (Slovenian name: Gorenjska), Lower Carniola (Slovenian: Dolenjska), and Inner Carniola (Slovenian: Notranjska). Politically the province was divided into eleven districts consisting of 359 municipalities; the provincial capital was the residence of the imperial governor. The districts were: Kamnik, Kranj, Radovljica, the neighbourhood of Ljubljana, Logatec, Postojna, Litija, Krsko, Novo Mesto, Crnomelj, and Gotschee or Kocevje. There were 31 judicial circuits.

The duchy was constituted by rescript of 20 December 1860, and by imperial patent of 26 February 1861, modified by legislation of 21 December 1867, granting power to the home parliament to enact all laws not reserved to the imperial diet, at which it was represented by eleven delegates, of whom two elected by the landowners, three by the cities, towns, commercial and industrial boards, five by the village communes, and one by a fifth curia by secret ballot, every duly registered male twenty-four years of age has the right to vote. The home legislature consisted of a single chamber of thirty-seven members, among whom the prince-bishop sits ex-officio. The emperor convened the legislature, and it is presided over by the governor. The landed interests elected ten members, the cities and towns eight, the commercial and industrial boards two, the village communes sixteen. In 1907, instead of these rules, universal and equal suffrage for all men was introduced. The business of the chamber was restricted to legislating on agriculture, public and charitable institutions, administration of communes, church and school affairs, the transportation and housing of soldiers in war and during manoeuvres, and other local matters. The land budget of 1901 amounted to 3,573,280 crowns ($714,656).

Modern era

In 1918, the duchy ceased to exist and its territory became part of the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and subsequently part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). The western part of the duchy, with the towns of Postojna, Ilirska Bistrica, Idrija and Šturje was annexed to Italy in 1920, but was subsequently also included into Yugoslavia in 1947.[11] Since 1991, the region has been part of an independent Slovenia.

Notes and references

- ^ In the extent at its dissolution.

- ^ Slovene pronunciation: [ˈkràːnska]. Source: "Slovenski pravopis 2001: Kranjska".

- ^ Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [krâːɲskaː]. Source: "Hrvatski jezični portal: Kranjska".

- ^ Perko, Drago; Orožen Adamič, Milan (1998). "Zgodovinske dežele Slovenije". Slovenija: pokrajina in ljudje (in Slovenian) (3. izdaja ed.). Mladinska knjiga. p. 16. ISBN 9788611150338.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Pipp, Lojze (1935). "Razvoj števila prebivalstva Ljubljane in bivše vojvodine Kranjske". Kronika slovenskih mest (in Slovenian). 2 (1). City Municipality of Ljubljana.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Perko, Drago; Orožen Adamič, Milan, eds. (1998). Slovenija – pokrajine in ljudje (in Slovenian). Mladinska knjiga. p. 16. ISBN 9788611150338.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Minahan, James. 2000. One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, p. 633.

- ^ Staab, Franz. 1976. Ostrogothic Geographers at the Court of Theodoric the Great: A Study of Some Sources of the Anonymous Cosmographer of Ravenna. Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies 7: 27–64, p. 54.

- ^ Plut-Pregelj, Leopoldina & Carole Rogel. 2010. The A to Z of Slovenia. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, p. 48.

- ^ Prothero, GW; Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section (1920). Carniola, Carinthia and Styria. Peace handbooks. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 11. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ Snoj, Marko. 2009. Etimološki slovar slovenskih zemljepisnih imen. Ljubljana: Modrijan and Založba ZRC, pp. 210–211.

- ^ See: Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

Further reading

- Dimitz, August (2013) [1875], History of Carniola: From Primeval Times to the death of Emperor Frederick III (1493), vol. I, Witter, Andrew J., translator, Slovenian Genealogical Society International, ISBN 978-1-48360-408-4

- Dimitz, August (2013) [1875], History of Carniola: From the Accession of Maximilian I (1493) to the Year 1813, vol. II, Witter, Andrew J., translator, Slovenian Genealogical Society International, ISBN 978-1-48360-410-7

- Dimitz, August (2013) [1875], History of Carniola: From the Accession of Archduke Karl to Leopold I (1564–1657), vol. III, Witter, Andrew J., translator, Slovenian Genealogical Society International, ISBN 978-1-48360-412-1

- Dimitz, August (2013) [1875], History of Carniola: To the end of French Rule in Illyria (1813), vol. IV, Witter, Andrew J., translator, Slovenian Genealogical Society International, ISBN 978-1-48360-417-6

See also

- History of Slovenia

- Duchy of Carniola

- March of Carniola

- Inner Austria

- Battle of Sisak

- Johann Weikhard von Valvasor

- The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola

- Flag of Slovenia

External links

- Slovenian Genealogical Society International, Inc. Announcement of publication of English translation of History of Carniola by August Dimitz from 1875

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Catholic Encyclopaedia

- Map – Carniola in 1849