Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe | |

|---|---|

Claude Chappe | |

| Born | December 25, 1763 |

| Died | January 23, 1805 (Aged 42) |

| Nationality | France |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects | semaphore system |

| Significant advance | telecommunications |

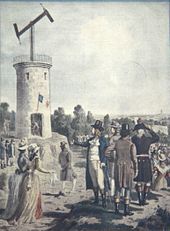

Claude Chappe (December 25, 1763 – January 23, 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. This was the first practical telecommunications system of the industrial age, making Chappe the first telecom mogul with his "mechanical internet."[1]

Life

Chappe was born in Brûlon, Sarthe, France, the grandson of a French baron. He was raised for church service, but lost his sinecure during the French Revolution. He was educated at the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen.[2]

His uncle was the astronomer Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche famed for his observations of the Transit of Venus in 1761 and again in 1769. The first book Claude read in his youth was his uncle's journal of the 1761 trip, "Voyage en Siberie". His brother, Abraham, wrote "Reading this book greatly inspired him, and gave him a taste for the physical sciences. From this point on, all his studies, and even his pastimes, were focused on that subject." Because of his astronomer uncle, Claude may also have become familiar with the properties of telescopes.[3]

He and his four unemployed brothers decided to develop a practical system of semaphore relay stations, a task proposed in antiquity, yet never realized.

Claude's brother, Ignace Chappe (1760–1829) was a member of the Legislative Assembly during the French Revolution. With his help, the Assembly supported a proposal to build a relay line from Paris to Lille (fifteen stations, about 120 miles), to carry dispatches from the war.

The Chappe brothers determined by experiment that the angles of a rod were easier to see than the presence or absence of panels. Their final design had two arms connected by a cross-arm. Each arm had seven positions, and the cross-arm had four more permitting a 196-combination code. The arms were from three to thirty feet long, black, and counterweighted, moved by only two handles. Lamps mounted on the arms proved unsatisfactory for night use. The relay towers were placed from 12 to 25 km (10 to 20 miles) apart. Each tower had a telescope pointing both up and down the relay line. Chappe first called his invention the "tachygraph", which means fast writer. A friend suggested a name meaning a far writer, telegraph.[1]

In 1792, the first messages were successfully sent between Paris and Lille.[4] In 1794 the semaphore line informed Parisians of the capture of Condé-sur-l'Escaut from the Austrians less than an hour after it occurred. Other lines were built, including a line from Paris to Toulon. The system was widely copied by other European states, and was used by Napoleon to coordinate his empire and army.[4]

In 1805, Claude Chappe committed suicide in Paris by throwing himself down a well at his hotel.[5] He was said to be depressed by illness, and claims by rivals that he had plagiarized from military semaphore systems.

In 1824 Ignace Chappe attempted to increase interest in using the semaphore line for commercial messages, such as commodity prices; however, the business community resisted.

In 1846, the government of France committed to a new system of electric telegraph lines. Many contemporaries warned of the ease of sabotage and interruption of service by cutting a wire. With the emergence of the electric telegraph, slowly the Chappe telegraph ended in 1852.[4]

Popular culture

The Chappe semaphore figures prominently in Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo. The Count bribes an underpaid operator to transmit a false message.

A bronze sculpture of Claude Chappe was erected at the crossing of Rue du Bac and Boulevard Raspail, in Paris. It was removed and melted down during the Nazi occupation of Paris, in 1941 or 1942.[6]

See also

References

- ^ a b Beyer, p. 60

- ^ Lycée Pierre Corneille de Rouen - History

- ^ The Early History of Data Networks

- ^ a b c French source: Tour du télégraphe Chappe

- ^ "Claude Chappe (French engineer)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ http://www.messynessychic.com/2016/01/07/where-the-statues-of-paris-were-sent-to-die/?utm_content=bufferb7325&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=buffer

Bibliography

- Beyer, Rick, The Greatest Stories Never Told, A&E Television Networks / The History Channel, ISBN 0-06-001401-6

External links

- French article: Les Télégraphes Chappe, l'Ecole Centrale de Lyon

- French article: Le télégraphe aérien, in Les merveilles de la science, de Louis Figuier, t. 2, pages 20-68

- Italian article: Francesco Frasca, Il telegrafo ottico dalla Rivoluzione francese alla guerra di Crimea, in Informazioni della Difesa, n°1, 2000, Roma: Stato Maggiore della Difesa, pp. 44-51