Confederate States of America: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

a test |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

In his farewell speech to the United States Congress, Davis made it clear that the secession crisis had been created by the Republican Party's failure "to recognize our domestic institutions [an acknowledged euphemism for slavery] which pre-existed the formation of the Union -- our property which was guarded by the Constitution."<ref>Coski pg. 23. The bracketed text was added by Coski.</ref><!--Your votes refuse to recognize our domestic institutions, which preexisted the formation of the Union--our property, which was guarded by the Constitution. You refuse us that equality without which we should be degraded if we remained in the Union.... Is there a senator on the other side who, to-day, will agree that we shall have equal enjoyment of the Territories of the United States? Is there one who will deny that we have equally paid in their purchases and equally bled in their acquisition in war?... Whose is the fault, then, if the Union be dissolved?... If you desire, at this last moment, to avert civil war, so be it; it is better so. If you will but allow us to separate from you peaceably, since we cannot live peaceably together, to leave with the rights we had before we were united, since we cannot enjoy them in the Union, then there are many relations, drawn from the associations of our (common) struggles from the Revolutionary period to the present day, which may be beneficial to you as well as to us |url=http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/gordon/gordon.html--> |

In his farewell speech to the United States Congress, Davis made it clear that the secession crisis had been created by the Republican Party's failure "to recognize our domestic institutions [an acknowledged euphemism for slavery] which pre-existed the formation of the Union -- our property which was guarded by the Constitution."<ref>Coski pg. 23. The bracketed text was added by Coski.</ref><!--Your votes refuse to recognize our domestic institutions, which preexisted the formation of the Union--our property, which was guarded by the Constitution. You refuse us that equality without which we should be degraded if we remained in the Union.... Is there a senator on the other side who, to-day, will agree that we shall have equal enjoyment of the Territories of the United States? Is there one who will deny that we have equally paid in their purchases and equally bled in their acquisition in war?... Whose is the fault, then, if the Union be dissolved?... If you desire, at this last moment, to avert civil war, so be it; it is better so. If you will but allow us to separate from you peaceably, since we cannot live peaceably together, to leave with the rights we had before we were united, since we cannot enjoy them in the Union, then there are many relations, drawn from the associations of our (common) struggles from the Revolutionary period to the present day, which may be beneficial to you as well as to us |url=http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/gordon/gordon.html--> |

||

Some southern religious leaders preached the cause of secession. [[Benjamin M. Palmer]] (1818-1902), pastor of the First [[Presbyterian Church]] of [[New Orleans]], thundered his support for secession in a [[Thanksgiving]] sermon in 1860, arguing that white Southerners had a right and duty to maintain slavery out of economic and social self-preservation, in order to act as "guardians" to the "affectionate and loyal" but "helpless" blacks, to safeguard global economic interests, and to defend religion against "atheistic" abolitionism.<ref>The text of [http://members.aol.com/jfepperson/palmer.htm Benjamin Palmer's "Thanksgiving Sermon"].</ref> His sermon was widely distributed across the region. Reverend Palmer's sermon stood in oppposition to the conservative Presbyterian position (i.e, of the [[Covenanters]], the original Presbyterians) that has taught that slavery ("man-stealing" in the Presbyterian vernacular) is against the Bible. <ref>The Presbyterian position on slavery [http://www.covenanter.org/Slavery/slaveryhome.htm "Negro Slavery Unjustifiable"].</ref> |

Some southern religious leaders preached the cause of secession. [[Benjamin M. Palmer]] (1818-1902), pastor of the First [[Presbyterian Church]] of [[New Orleans]], thundered his support for secession in a [[Thanksgiving]] sermon in 1860, arguing that white Southerners had a right and duty to maintain slavery out of economic and social self-preservation, in order to act as "guardians" to the "affectionate and loyal" but "helpless" blacks, to safeguard global economic interests, and to defend religion against "atheistic" abolitionism.<ref>The text of [http://members.aol.com/jfepperson/palmer.htm Benjamin Palmer's "Thanksgiving Sermon"].</ref> His sermon was widely distributed across the region. Reverend Palmer's sermon stood in oppposition to the conservative Presbyterian position (i.e, of the [[Covenanters]], the original Presbyterians) that has taught that slavery ("man-stealing" in the Presbyterian vernacular) is against the Bible. <ref>The Presbyterian position on slavery [http://www.covenanter.org/Slavery/slaveryhome.htm "Negro Slavery Unjustifiable"].</ref> Testing <ref>Ta me go OK, August 2008</ref> |

||

====Seceding states==== |

====Seceding states==== |

||

Revision as of 23:24, 10 August 2008

Confederate States of America | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861–1865 | |||||||||

| Motto: Deo Vindice (Latin) "With God our Vindicator" | |||||||||

| Anthem: (none official) "God Save the South" (unofficial) "The Bonnie Blue Flag" (popular) "Dixie" (traditional) | |||||||||

States under CSA control

States and territories claimed by CSA without formal secession and/or control | |||||||||

| Capital | Montgomery, Alabama (until May 29 1861) Richmond, Virginia (May 29 1861–April 2 1865) Danville, Virginia (from April 3 1865) | ||||||||

| Largest city | New Orleans (4 February 1861–May 1 1862) (captured) Richmond (May1 1862–surrender) | ||||||||

| Common languages | English (de facto) | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

| Legislature | Congress of the Confederate States | ||||||||

| Historical era | American Civil War | ||||||||

• Confederacy formed | February 4 1861 1861 | ||||||||

| April 12 1861 | |||||||||

• Dissolution | April 11 1865 1865 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 18601 | 1,995,392 km2 (770,425 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 18601 | 9,103,332 | ||||||||

• slaves2 | 3,521,110 | ||||||||

| Currency | CSA dollar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

1 Area and population values do not include Missouri and Kentucky nor the Territory of Arizona. Water area: 5.7%. 2 Slaves included in above population count 1860 Census | |||||||||

The Confederate States of America (also called the Confederacy, the Confederate States, and CSA) was the government formed by eleven southern states of the United States of America between 1861 and 1865. Its de facto control over its claimed territory varied during the war, and was linked to the fortunes of its military in battle.

Seven states declared their independence from the United States before Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as President; four more did so after the Civil War began at the Battle of Fort Sumter. The United States of America ("The Union") held secession illegal and refused recognition of the Confederacy. Although British and French commercial interests sold the Confederacy warships and materials, no European nation officially recognized the CSA as an independent country.

The CSA effectively collapsed when Robert E. Lee and Joseph Johnston surrendered their armies in April 1865. The last meeting of its Cabinet took place in Georgia in May. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured by Union troops near Irwinsville, Georgia on May 10, 1865. Nearly all remaining Confederate forces surrendered by the end of June. A decade-long process known as Reconstruction temporarily gave civil rights and the right to vote to the freedmen, expelled ex-Confederate leaders from office, and re-admitted the states to representation in Congress.

History

Causes of secession

By 1860 sectional disagreements between North and South revolved primarily around the maintenance or expansion of slavery. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust observed that, "leaders of the secession movement across the South cited slavery as the most compelling reason for southern independence."[1] Related and intertwined secondary issues also fueled the dispute; these secondary differences (real or perceived) included tariffs, agrarianism vs. industrialization, and states' rights. The immediate spark for secession was the victory of the Republican Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Civil War historian James McPherson wrote:

To southerners the election’s most ominous feature was the magnitude of Republican victory north of the 41st parallel. Lincoln won more than 60 percent of the vote in that region, losing scarcely two dozen counties. Three-quarters of the Republican congressmen and senators in the next Congress would represent this “Yankee” and antislavery portion of the free states. These facts were “full of portentous significance” declared the New Orleans Crescent. “The idle canvas prattle about Northern conservatism may now be dismissed,” agreed the Richmond Examiner. “A party founded on the single sentiment... of hatred of African slavery, is now the controlling power.” No one could any longer “be deluded... that the Black Republican party is a moderate” party, pronounced the New Orleans Delta. “It is in fact, essentially, a revolutionary party.”[2]

Four of the seceding states, the Deep South states of South Carolina,[3] Mississippi,[4] Georgia,[5] and Texas,[6] issued formal declarations of causes, each of which identified the threat to slaveholders’ rights as the cause of, or a major cause of, secession; Georgia also claimed a general Federal policy of favoring Northern over Southern economic interests. In what later came to be known as the Cornerstone Speech, C.S. Vice President Alexander Stephens declared that the "cornerstone" of the new government "rest[ed] upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth".[7]

Historian William J. Cooper Jr., in his biography of the Confederate president Jefferson Davis, wrote, “From at least the time of the American Revolution white southerners defined their liberty, in part, as the right to own slaves and to decide the fate of the institution without any outside interference.”[8] Speaking specifically of Davis, Cooper wrote:

For his entire life he believed in the superiority of the white race. He also owned slaves, defended slavery as moral and as a social good, and fought a great war to maintain it. After 1865 he opposed new rights for blacks. He rejoiced at the collapse of Reconstruction and the reassertion of white superiority with its accompanying black subordination.[9]

In his farewell speech to the United States Congress, Davis made it clear that the secession crisis had been created by the Republican Party's failure "to recognize our domestic institutions [an acknowledged euphemism for slavery] which pre-existed the formation of the Union -- our property which was guarded by the Constitution."[10]

Some southern religious leaders preached the cause of secession. Benjamin M. Palmer (1818-1902), pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of New Orleans, thundered his support for secession in a Thanksgiving sermon in 1860, arguing that white Southerners had a right and duty to maintain slavery out of economic and social self-preservation, in order to act as "guardians" to the "affectionate and loyal" but "helpless" blacks, to safeguard global economic interests, and to defend religion against "atheistic" abolitionism.[11] His sermon was widely distributed across the region. Reverend Palmer's sermon stood in oppposition to the conservative Presbyterian position (i.e, of the Covenanters, the original Presbyterians) that has taught that slavery ("man-stealing" in the Presbyterian vernacular) is against the Bible. [12] Testing [13]

Seceding states

|

|

Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territory |

|

Allied tribes in Indian Territory |

Seven states seceded by February 1861:

- South Carolina (December 20 1860),[14]

- Mississippi (January 9 1861),[15]

- Florida (January 10 1861),[16]

- Alabama (January 11 1861),[17]

- Georgia (January 19, 1861),[18]

- Louisiana (January 26 1861),[19]

- Texas (February 1 1861).[20]

After Lincoln called for troops, four more states seceded:

- Virginia (April 17 1861);[21] there was also a rump Union government of Virginia[22]

- Arkansas (May 6, 1861),[23]

- North Carolina (May 20 1861)[24]

- Tennessee (June 8 1861).[25][26]

Two more slave states had rival (or rump) secessionist governments. The Confederacy admitted them, but the pro-Confederate state governments were soon in exile and never controlled the states:

- Missouri did not secede but a rump group proclaimed secession (October 31 1861).[27][28]

- Kentucky did not secede but a rump, unelected group proclaimed secession (November 20 1861).[29][30]

Additionally, portions of modern-day Oklahoma and Arizona and New Mexico were claimed as Confederate territories.

Although the slave states of Maryland and Delaware did not secede, many citizens joined the Army of Northern Virginia.

Rise and fall of the Confederacy

The American Civil War broke out in April 1861 with the Battle of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Federal troops of the U.S. had retreated to Fort Sumter soon after South Carolina declared its secession. U.S. President Buchanan had attempted to resupply Sumter by sending the Star of the West, but Confederate forces fired upon the ship, driving it away. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln also attempted to resupply Sumter. Lincoln notified South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens that "an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, [except] in case of an attack on the fort." However, suspecting that just such an attempt to reinforce the fort would be made, the Confederate cabinet decided at a meeting in Montgomery to capture Fort Sumter before the relief fleet arrived.

On April 12 1861, Confederate troops, following orders from Davis and his Secretary of War, fired upon the federal troops occupying Fort Sumter, forcing their surrender.

Following the Battle of Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for the remaining states in the Union to send troops to recapture Sumter and other forts and customs-houses[31] in the South that Confederate forces had claimed, some by force. This proclamation was made before Congress could convene on the matter, and the original request from the War Department called for volunteers for only three months of duty.[31] Lincoln's call for troops resulted in four more states voting to secede, rather than provide troops for the Union. Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina joined the Confederacy, bringing the total to eleven states. Once Virginia joined the Confederate States, the Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia. All but two major battles (Antietam and Gettysburg) took place in Confederate territory.

Alexander H. Stephens maintained that Lincoln's attempt to reinforce Sumter had provoked the war.[32]

Kentucky was a border state during the war and, for a time, had two state governments, one supporting the Confederacy and one supporting the Union. The original government remained in the Union after a short-lived attempt at neutrality, but a rival faction from that state was accepted as a member of the Confederate States of America; it did not control any territory. A more complex situation surrounds the Missouri Secession. Although the Confederacy considered Missouri a member of the Confederate States of America; it did not control any territory. With Kentucky and Missouri, the number of Confederate states can be counted as thirteen; later versions of Confederate flags had thirteen stars, reflecting the Confederacy's claims to those states.

The five tribal governments of the Indian Territory — which became Oklahoma in 1907 — also mainly supported the Confederacy, providing troops and one General officer. They were represented in the Confederate Congress after 1863 by Elias Cornelius Boudinot representing the Cherokee, and Samuel Benton Callahan representing the Seminole and Creek people. The Cherokee, in their declaration of causes, gave as reasons for aligning with the Confederacy the similar institutions and interests of the Cherokee nation and the Southern states, alleged violations of the Constitution by the North, claimed that the North was waging war against Southern commercial and political freedom and for the abolition of slavery in general and in the Indian Territory in particular, and that the North intended to seize Indian lands as had been done in the past[33].

Citizens at Mesilla and Tucson in the southern part of New Mexico Territory formed a secession convention and voted to join the Confederacy on March 16 1861, and appointed Lewis Owings as the new territorial governor. In July, Mesilla appealed to Confederate troops in El Paso, Texas, under Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor for help in removing the Union Army under Major Isaac Lynde that was stationed nearby. The Confederates defeated Lynde at the Battle of Mesilla on July 27. After the battle, Baylor established a territorial government for the Confederate Arizona Territory and named himself governor. In 1862, a New Mexico Campaign was launched under General Henry Hopkins Sibley to take the northern half of New Mexico. Although Confederates briefly occupied the territorial capital of Santa Fe, they were defeated at Glorietta Pass in March and retreated, never to return.

The northernmost slave states (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia) were contested territory, but the Union won control by 1862. In 1861, martial law was declared in Maryland (the state which borders the U.S. capital, Washington, D.C., on three sides) to block attempts at secession. Delaware, also a slave state, never considered secession, nor did Washington, D.C. In 1861, a Unionist legislature in Wheeling, Virginia seceded from Virginia, claiming 48 counties, and joined the United States in 1863 as the state of West Virginia with a constitution that gradually abolished slavery.

Attempts to secede from the Confederate States of America by some counties in East Tennessee were held in check by Confederate declarations of martial law[34][35].

The surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia by General Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9 1865, is generally taken as the end of the Confederate States. President Davis was captured at Irwinville, Georgia, on May 10, and the remaining Confederate armies surrendered by June 1865. The last Confederate flag was hauled down from CSS Shenandoah on November 6 1865.

Government and politics

Constitution

President 1861-1865

The Southern leaders met in Montgomery, Alabama, to write their constitution. The Confederate States Constitution reveals much about the motivations for secession from the Union. Although much of it was copied verbatim from the United States Constitution, it contained several explicit protections of the institution of slavery, though the existing ban on international slave trading was maintained. In certain areas, the Confederate Constitution gave greater powers to the states, or curtailed the powers of the central government more, than the U.S. Constitution of the time did, but in other areas, the states actually lost rights they had under the U.S. Constitution. Although the Confederate Constitution, like the U.S. Constitution, contained a commerce clause, the Confederate version prohibited the central government from using revenues collected in one state for funding internal improvements in another state. The Confederate Constitution's equivalent to the U.S. Constitution's general welfare clause prohibited protective tariffs (but allowed tariffs for domestic revenue), and spoke of "carry[ing] on the Government of the Confederate States" rather than providing for the "general welfare". State legislatures were given the power to impeach officials of the Confederate government in some cases. On the other hand, the Confederate Constitution contained a necessary and proper clause and a supremacy clause that were essentially identical to those of the U.S. Constitution.

The Confederate Constitution did not specifically include a provision allowing states to secede; the Preamble spoke of each state "acting in its sovereign and independent character" but also of the formation of a "permanent federal government". During the debates on drafing the Confederate Constitution, a proposal was made that would have allowed states to secede from the Confederacy. The proposal was tabled with only the South Carolina delegates voting in favor of considering the motion.[36] States were also explicitly denied the power to bar slaveholders from other parts of the Confederacy from bringing their slaves into any state of the Confederacy or to interfere with the property rights of slave owners traveling between different parts of the Confederacy. In contrast with the secular language of the United States Constitution, the Confederate Constitution overtly asked God's blessing ("invoking the favor of Almighty God.")

The President of the Confederate States of America was to be elected to a six-year term, but could not be re-elected. (The only president was Jefferson Davis; the Confederacy was defeated by the Union before he completed his term.) One unique power granted to the Confederate president was his ability to subject a bill to a line item veto, a power held by some state governors. The Confederate Congress could overturn either the general or the line item vetoes with the same two-thirds majorities that are required in the U.S. Congress. In addition, appropriations not specifically requested by the executive branch required passage by a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress.

Printed currency in the forms of bills and stamps was authorized and put into circulation, although by the individual states in the Confederacy's name. The government considered issuing Confederate coinage. Plans, dies and four "proofs" were created, but a lack of bullion prevented any minting.

Executive

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Jefferson Davis | 1861-1865 |

| Vice President | Alexander Stephens | 1861-1865 |

| Secretary of State | Robert Toombs | 1861 |

| Robert M.T. Hunter | 1861-1862 | |

| Judah P. Benjamin | 1862-1865 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Christopher Memminger | 1861-1864 |

| George Trenholm | 1864-1865 | |

| John H. Reagan | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Leroy Pope Walker | 1861 |

| Judah P. Benjamin | 1861-1862 | |

| George W. Randolph | 1862 | |

| James Seddon | 1862-1865 | |

| John C. Breckinridge | 1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Stephen Mallory | 1861-1865 |

| Postmaster General | John H. Reagan | 1861-1865 |

| Attorney General | Judah P. Benjamin | 1861 |

| Thomas Bragg | 1861-1862 | |

| Thomas H. Watts | 1862-1863 | |

| George Davis | 1864-1865 | |

Legislative

The legislative branch of the Confederate States of America was the Confederate Congress. Like the United States Congress, the Confederate Congress consisted of two houses: the Confederate Senate, whose membership included two senators from each state (and chosen by the state legislature), and the Confederate House of Representatives, with members popularly elected by residents of the individual states.

Provisional Congress

For the first year, the unicameral Provisional Confederate Congress was the confederacy's legislative branch.

President of the Provisional Congress

- Howell Cobb, Sr. of Georgia - February 4 1861-February 17 1862

Presidents pro tempore of the Provisional Congress

- Robert Woodward Barnwell of South Carolina - February 4 1861

- Thomas Stanhope Bocock of Virginia - December 10-21, 1861 and January 7-8, 1862

- Josiah Abigail Patterson Campbell of Mississippi - December 23-24, 1861 and January 6 1862

Sessions of the Confederate Congress

Tribal Representatives to Confederate Congress

- Elias Cornelius Boudinot 1862-65 - Cherokee

- Burton Allen Holder 1864-1865 Chickasaw

- Robert McDonald Jones 1863-65 - Choctaw

Judicial

A Judicial branch of the government was outlined in the constitution, but the "Supreme Court of the Confederate States" was never created or seated because of the ongoing war; the state and local courts generally continued to operate as they had been, simply recognizing the CSA as the national government[37]. Some Confederate district courts were, however, established within some of the individual states of the Confederate States of America; namely, South Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia (and possibly others). At the end of the war, U.S. district courts resumed jurisdiction[38].

Supreme court - not established

District Court

- Asa Biggs 1861-1865

- John White Brockenbrough 1861

- Alexander Mosby Clayton 1861

- Jesse J. Finley 1861-1862

Civil liberties

The Confederacy actively used the military to arrest people suspected of loyalty to the United States. Historian Mark Neely found 2,700 names of men arrested and estimated the full list was much longer. They arrested at about the same rate as the Union arrested Confederate loyalists. Neely concludes:

The Confederate citizen was not any freer than the Union citizen — and perhaps no less likely to be arrested by military authorities. In fact, the Confederate citizen may have been in some ways less free than his Northern counterpart. For example, freedom to travel within the Confederate states was severely limited by a domestic passport system.[39]

Capital

Served as the last Confederate Capitol building.

The capital of the Confederate States of America was Montgomery, Alabama, from February 4 until May 29 1861. Richmond, Virginia, was named the new capital on May 30 1861. Shortly before the end of the war, the Confederate government evacuated Richmond, planning to relocate farther south. Little came of these plans before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House. Danville, Virginia, served as the last capital of the Confederate States of America, from April 3 to April 10 1865.

International diplomacy

Once the war with the United States began, the best hope for the survival of the Confederacy was military intervention by Britain and France. The United States realized this as well and made it clear that recognition of the Confederacy meant war with the United States — and the cutoff of food shipments into Britain. The Confederates who had believed that "cotton is king"[40] — that is, Britain had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton — were proven wrong.[41] The British instead focused more heavily on cotton and textile produced in the British Raj and Russia,[42] with the French also ramping up production in Algeria.[42] Notably, in the early years of the war, demand for textiles, and hence cotton, was weak.[43] In time, the war and Union blockade of the South caused economic hardship in textile-producing areas of England such as Lancashire, which depended heavily on cotton exports from the seceding states;[44] however, abolitionist sentiment among English workers ran counter to this economic interest in Confederate victory.[45]

During its existence, while the Confederate government sent repeated delegations to Europe, historians do not give them high marks for diplomatic skills. James M. Mason was sent to London as Confederate minister to Queen Victoria, and John Slidell was sent to Paris as minister to Napoleon III. Both were able to obtain private meetings with high British and French officials, but they failed to secure official recognition for the Confederacy. When Britain and the United States came dangerously close to war during the Trent Affair, where two Confederate agents travelling on a British ship had been illegally seized by the U.S. Navy in late 1861, it seemed possible that the Confederacy would see its much vaunted recognition.[46] When Lincoln released the two, however, tensions cooled, and in the end the episode was of no help to the Confederacy.[47]

Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord Russell, Napoleon III, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, were interested in the idea of recognition of the Confederacy, or at least of offering a mediation. Recognition meant certain war with the United States, loss of American grain, loss of exports to the United States, loss of huge investments in American securities, possible war in Canada and other North American colonies, much higher taxes, many lives lost and a severe threat to the entire British merchant marine, in exchange for the possibility of some cotton. Many party leaders and the public wanted no war with such high costs and meager benefits. Recognition was considered following the Second Battle of Bull Run when the British government was preparing to mediate in the conflict, but the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam and Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, combined with internal opposition, caused the government to back away.

In November 1863, Confederate diplomat A. Dudley Mann met Pope Pius IX and received a letter addressed "to the Illustrious and Honorable Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America.” Mann, in his dispatch to Richmond, interpreted the letter as "a positive recognition of our Government," and some have mistakenly viewed it as a de facto recognition of the C.S.A. Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, however, interpreted it as "a mere inferential recognition, unconnected with political action or the regular establishment of diplomatic relations" and thus did not assign it the weight of formal recognition.[48] For the remainder of the war, Confederate commissioners continued meeting with Cardinal Antonelli, the Vatican Secretary of State. In 1864, Catholic Bishop Patrick N. Lynch of Charleston traveled to the Vatican with an authorization from Jefferson Davis to represent the Confederacy before the Holy See. That same year, Davis sent Duncan Kenner to France and England with an offer to emancipate Southern slaves in exchange for recognition of the Confederacy from France and Great Britain.[49] This attempt was unsuccessful.

No country appointed any diplomat officially to the Confederacy, but several maintained their consuls in the South who had been appointed before the war. In 1861, Ernst Raven applied for approval as the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha consul, but he was a citizen of Texas and there is no evidence that officials in Saxe-Coburg and Gotha knew what he was doing. In 1863, the Confederacy expelled all foreign consuls (all of them British or French diplomats) for advising their subjects to refuse to serve in combat against the U.S.

Throughout the war, most European powers adopted a policy of neutrality, meeting informally with Confederate diplomats but withholding diplomatic recognition. None ever sent an ambassador or official delegation to Richmond. However, they applied international law principles that recognized the Union and Confederate sides as belligerents. Canada allowed both Confederate and Union agents to work openly within its borders, and some state governments in northern Mexico negotiated local agreements to cover trade on the Texas border.

"Died of states' rights"

Historian Frank Lawrence Owsley argued that the Confederacy "died of states' rights."[50] According to Owsley, strong-willed governors and state legislatures in the South refused to give the national government the soldiers and money it needed because they feared that Richmond was encroaching on the rights of the states. Georgia's governor Joseph Brown warned that he saw the signs of a deep-laid conspiracy on the part of Jefferson Davis to destroy states' rights and individual liberty. Brown declaimed: "Almost every act of usurpation of power, or of bad faith, has been conceived, brought forth and nurtured in secret session." To grant the Confederate government the power to draft soldiers was the "essence of military despotism."[51] In 1863 governor Pendleton Murrah of Texas insisted that Texas troops were needed for self-defense (against Indians or a threatened Union invasion), and refused to send them East.[52] Zebulon Vance, the governor of North Carolina was notoriously hostile to Davis and his demands. Opposition to conscription in North Carolina was intense and its results were disastrous for recruiting. Governor Vance's faith in states' rights drove him into a stubborn opposition.[53]

Vice President Stephens broke publicly with President Davis, saying any accommodation would only weaken the republic, and he therefore had no choice but to break publicly with the Confederate administration and the president. Stephens charged that to allow Davis to make "arbitrary arrests" and to draft state officials conferred on him more power than the English Parliament had ever bestowed on the king. "History proved the dangers of such unchecked authority." He added that Davis intended to suppress the peace meetings in North Carolina and "put a muzzle upon certain presses" (especially the antiwar newspaper Raleigh Standard) in order to control elections in that state. Echoing Patrick Henry's "give me liberty or give me death" Stephens warned the Southerners they should never view liberty as "subordinate to independence" because the cry of "independence first and liberty second" was a "fatal delusion." As historian George Rable concludes, "For Stephens, the essence of patriotism, the heart of the Confederate cause, rested on an unyielding commitment to traditional rights. In his idealist vision of politics, military necessity, pragmatism, and compromise meant nothing."[54]

The survival of the Confederacy depended on a strong base of civilians and soldiers devoted to victory. The soldiers performed well, though increasing numbers deserted in the last year, and the Confederacy was never able to replace casualties as the Union could. The civilians, although enthusiastic in 1861-62 seem to have lost faith in the nation's future by 1864, and instead looked to protect their homes and communities. As Rable explains, "As the Confederacy shrank, citizens' sense of the cause more than ever narrowed to their own states and communities. This contraction of civic vision was more than a crabbed libertarianism; it represented an increasingly widespread disillusionment with the Confederate experiment.[55]

Relations with the United States

For the four years of its existence, the Confederate States of America asserted its independence and appointed dozens of diplomatic agents abroad. The United States government, by contrast, asserted that the Southern states were states in rebellion and refused any formal recognition of their status. Thus, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward issued formal instructions to Charles Francis Adams, the new minister to Great Britain:

You will indulge in no expressions of harshness or disrespect, or even impatience concerning the seceding States, their agents, or their people. But you will, on the contrary, all the while remember that those States are now, as they always heretofore have been, and, notwithstanding their temporary self-delusion, they must always continue to be, equal and honored members of this Federal Union, and that their citizens throughout all political misunderstandings and alienations, still are and always must be our kindred and countrymen.[56]

However, if the British seemed inclined to recognize the Confederacy, or even waver in that regard, they were to be sharply warned, with a strong hint of war:

[if Britain is] tolerating the application of the so-called seceding States, or wavering about it, you will not leave them to suppose for a moment that they can grant that application and remain friends with the United States. You may even assure them promptly, in that case, that if they determine to recognize, they may at the same time prepare to enter into alliance with the enemies of this republic.[57]

The Confederate Congress responded to the hostilities by formally declaring war on the United States in May 1861 — calling it "The War between the Confederate States of America and the United States of America."[58] The Union government never declared war but conducted its war efforts under a proclamation of blockade and rebellion. After the war the states were readmitted to representation in the US Congress. Mid-war negotiations between the two sides occurred without formal political recognition, though the laws of war governed military relationships.

Four years after the war, in 1869, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Texas v. White that secession was unconstitutional and legally null. The court's opinion was authored by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Jefferson Davis, former president of the Confederacy, and Alexander Stephens, its former vice-president, both penned arguments in favor of secession's legality, most notably Davis' The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

Effect upon British North America

British North America reacted in 1867, by instituting Canadian Confederation. Covert British aid to the CSA during the War was in defence of Canada, to avoid a repetition of the War of 1812, in an era when the USA was much stronger and had just proven its mettle. Furthermore, it can be argued that contemporary issues which inspired the Whig Party (United States), also affected BNA during the Rebellions of 1837 and which were among the many frustrations which led to the change in government infrastructure by both countries, for self-preservation from Federalist expansionisms, whether along Democratic or Republican party lines. In this case, those Whigs hearkened to the tradition of British Insularism and the Hartford Convention, rather than Napoleonic Continentalism which had been adopted by the Union after the French Revolution.

The new government stipulated the relinquishment of ex-Colonial States' Rights to individually settle in pre-Indiana (see Northwest Territory), with a promised treasure of the Louisiana Purchase (cf. Southwest Territory) by the Federal government. Manifest Destiny for the cause of Continentalism was the rallying cry of the Union, which wanted to amass more land thought to be compensation for the people who fought the French and Indian War (and still expected by Britain to pay wartime expenses), having enticed Easterners to settle the quasi-British Oregon Country (which was taken to be New Albion and thus, belonging to the Crown, without license for settlement by the ex-Colonists). This all was after the Union rounded off affairs in Louisiana by acquiring Florida Territory, formerly a British Colonial possession and therefore thought to be "retaken" by the new central government, although without apparent benefit to any individual State, while these newfound American territories were the reserve of the Federal government alone. American expansion insofar as the Alaska purchase (undertaken by the newly freed hands of Washington, DC), was what put the nail in the coffin of BNA inaction, fearing that the USA did have the willpower to do to them what was done to the CSA. On the other hand, Texan and Hawaiian annexations in the context of this fear, had less of a direct impact on Canada, even though it did give cause for glaring fear, since they were similar to the suppression and annexation of the CSA as a formerly independent nation, except were like Canada, being peripheral nations without direct investment in the American system.

All of this contributed to what is known as "Canadian nationalism" and such anti-American perception that the USA has been hypocritical, for its actions in the Revolution, vis a vis subsequent periods, when it "denied the rights" of other independent nations through warfare, as the USA did consider itself an independent nation in 1776 (the supposed inspiration behind Confederate independence), when its own aspirations were fought down by the British Parliament. In truth, many of the early Founding Fathers of the United States were not complete radicals and wished to remain within the framework of the Empire, as Canada was later to do--such people included George Washington (another inspiration for the CSA). In effect, the story is quite similar to Anglocentric perceptions of the French, after the Hundred Years' War, when the French called Joan of Arc their liberator from English domination, but thenceforth became the principle expansionist country in Europe, through the House of Bourbon.

Furthermore, the type of British government which was establishmentary in the South before the American Revolution (e.g. Colony and Dominion of Virginia), but rejected in what would later become the Union (e.g. Dominion of New England) of the Civil War era, had been loosely that which was adopted in Canada (see Dominion). After the War, the USA and British Empire spent decades of cooling off their causes of conflict and it was only after the South Seas arrangement of Australia and New Zealand (where pre-Revolutionary convicts meant for Georgia were planted), as well as South Africa (a White minority establishment, albeit without institutional slavery) were brought in line with the Canadian model; only after the Spanish-American War brought criss-cross political affinities into alignment. Most American colonists and convicts left Britain through serious grievances, which affected not only the way they dealt with London, but also how they would treat a new government, even established by themselves--with only London as their model by experience to draw upon. It was through this, the UK's later exemplary concessions of colonial autonomy to the Old Commonwealth, proving something beneficial or impressive to American prejudices about imperial governent and the US's defeat of Spain, Britain's oldest colonial foe (whereupon the USA experimented with a Commonwealth-style Governor-General--see Commonwealth#Australia), that the Special Relationship (US-UK) gradually came into effect, pointedly against Germany and her allies (including the British Royal Family, which culminated in renaming the dynasty to the House of Windsor and the Edward VIII abdication crisis), as the "big three" of competing industrial nations well in the 20th century.

The fall of the CSA, ironically and eventually led to the North Atlantic triangle, which preserves for Canada many of the aspirations sought by the CSA, although obviously not within the Southern territory that was fought over to defend/promote these principles of government. The other differences between the American Confederate and Canadian Confederate systems, is that in the former there was slavery and in the latter, there is the monarchy--each of these situations were untenable within the other's polity, but there were/are otherwise, no serious differences, especially in the present era of an Anglosphere and the UK-USA Security Agreement that bridges sovereignty on account of religious, political and cultural similarities. These were also, aspirations sought by the Antebellum South, building up to the Civil War era when massive immigration in the North, had begun threatening to end, what have been deemed "Anglo-Celtic" ways treasured by so-called "old stock" Americans--a majority still, in the Southern States, known in other areas and especially to Irish Catholics, as White Anglo-Saxon Protestants.

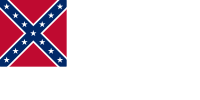

Confederate flags

The first official flag of the Confederate States of America, called the "Stars and Bars", had seven stars, for the seven states that initially formed the Confederacy. This flag was sometimes difficult to distinguish from the Union flag under battle conditions, so the flag was changed to the "Stainless Banner." The union of the Stainless Banner, known as the "Southern Cross", became the one more commonly used in military operations. The Southern Cross had 13 stars, adding the four states that joined the Confederacy after Fort Sumter, and the two divided states of Kentucky and Missouri. Due to similarities between the "Stainless Banner" and a white flag, a red stripe was appended vertically to the end of the flag, creating the third of the national flags.

Because of its depiction in 20th century popular media, the "Southern Cross" is a flag commonly associated with the Confederacy today. The actual "Southern Cross" is a square-shaped flag, but the more commonly seen rectangular flag is actually the flag of the First Tennessee Army, also known as the Naval Jack because it was first used by the Confederate Navy.

Geography

The Confederate States of America claimed a total of 2,919 miles (4,698 km) of coastline, thus a large part of its territory lay on the seacoast with level and often sandy or marshy ground. Most of the interior portion was arable farmland, though much was also hilly and mountainous, and the far western territories were deserts. The lower reaches of the Mississippi River bisected the country, with the western half often referred to as the Trans-Mississippi. The highest point (excluding Arizona and New Mexico) was Guadalupe Peak in Texas at 8,750 feet (2,667 m).

Climate

Much of the area claimed by the Confederate States of America had a humid subtropical climate with mild winters and long, hot, humid summers. The climate and terrain varied to semi-arid steppe and arid desert, west of longitude 96 degrees west. The subtropical climate made winters mild but allowed infectious diseases to flourish. Consequently, disease killed more soldiers than died in combat.

River system

In peacetime, the vast system of navigable rivers allowed for cheap and easy transportation of farm products. The railroad system was built as a supplement, tying plantation areas to the nearest river or seaport. The vast geography made for difficult Union logistics, and Union soldiers were used to garrison captured areas and protect rail lines. Nevertheless, the Union Navy seized most of the navigable rivers by 1862, making its own logistics easy and Confederate movements difficult. After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, it became impossible for units to cross the Mississippi since Union gunboats constantly patrolled it. The South thus lost use of its western regions.

Railroad system

The outbreak of war had a depressing effect on the economic fortunes of the Confederate railroad industry. With cotton crop being hoarded in an attempt to entice European intervention, railroads were bereft of their main source of income.[59] Many were forced to lay off employees, and in particular, let go skilled technicians and engineers.[59] For the early years of the war, the Confederate government had a hands off approach to the railroads. It wasn't until mid-1863 that the Confederate government initiated an overall policy, and it was confined solely to aiding the war effort.[60] With the legislation of impressment the same year, rail roads and their rolling stock, came under the defacto control of the military.

In the last year before the end of the war, the Confederate railroad system was always on the verge of collapse. The impressment policy of Quarter-master's ran the rails ragged; feeder lines would be scraped in order to lay down replacement steel for trunk lines, and the continual use of rolling stock wore them down faster than they could be replaced.[61]

Rural areas

The area claimed by the Confederate States of America was overwhelmingly rural. Small towns of more than 1,000 were few — the typical county seat had a population of fewer than 500 people. Cities were rare. New Orleans was the only Southern city in the list of the ten largest U.S. cities in the 1860 census, and it was captured by the Union in 1862. Only 13 Confederate cities ranked among the top 100 U.S. cities in 1860, most of them ports whose economic activities were shut down by the Union blockade. The population of Richmond swelled after it became the national capital, reaching an estimated 128,000 in 1864 (Dabney 1990:182). Other large Southern cities (Baltimore, St. Louis, Louisville, and Washington, as well as Wheeling, West Virginia, and Alexandria, Virginia) were never under the control of the Confederate government.

| # | City | 1860 population | 1860 U.S. rank | Return to U.S. control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | New Orleans, Louisiana | 168,675 | 6 | 1862 |

| 2. | Charleston, South Carolina | 40,522 | 22 | 1865 |

| 3. | Richmond, Virginia | 37,910 | 25 | 1865 |

| 4. | Mobile, Alabama | 29,258 | 27 | 1865 |

| 5. | Memphis, Tennessee | 22,623 | 38 | 1862 |

| 6. | Savannah, Georgia | 22,292 | 41 | 1864 |

| 7. | Petersburg, Virginia | 18,266 | 50 | 1865 |

| 8. | Nashville, Tennessee | 16,988 | 54 | 1862 |

| 9. | Norfolk, Virginia | 14,620 | 61 | 1862 |

| 10. | Augusta, Georgia | 12,493 | 77 | 1865 |

| 11. | Columbus, Georgia | 9,621 | 97 | 1865 |

| 12. | Atlanta, Georgia | 9,554 | 99 | 1864 |

| 13. | Wilmington, North Carolina | 9,553 | 100 | 1865 |

(See also Atlanta in the Civil War, Charleston, South Carolina, in the Civil War, Nashville in the Civil War, New Orleans in the Civil War, and Richmond in the Civil War).

Economy

The Confederacy had an agrarian economy with exports, to a world market, of cotton, and, to a lesser extent, tobacco and sugarcane. Local food production included grains, hogs, cattle, and gardens. The 11 states produced $155 million in manufactured goods in 1860, chiefly from local grist mills, and lumber, processed tobacco, cotton goods and naval stores such as turpentine. By the 1830s, the 11 states produced more cotton than all of the other countries in the world combined. The CSA adopted a low tariff of 15 per cent, but imposed it on all imports from other countries, including the Union states[62]. The tariff mattered little; the Confederacy's ports were blocked to commercial traffic by the Union's blockade, and very few people paid taxes on goods smuggled from the Union states. The government collected about $3.5 million in tariff revenue from the start of their war against the Union to late 1864. The lack of adequate financial resources led the Confederacy to finance the war through printing money, which led to high inflation.

Armed forces

The military armed forces of the Confederacy were composed of three branches:

The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and had been appointed to senior positions in the Confederate armed forces. Many had served in the Mexican-American War (including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis), but others had little or no military experience (such as Leonidas Polk, who had attended West Point but did not graduate.) The Confederate officer corps was composed in part of young men from slave-owning families, but many came from non-owners. The Confederacy appointed junior and field grade officers by election from the enlisted ranks. Although no Army service academy was established for the Confederacy, many colleges of the South (such as the The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute) maintained cadet corps that were seen as a training ground for Confederate military leadership. A naval academy was established at Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia[63] in 1863, but no midshipmen had graduated by the time the Confederacy collapsed.

The soldiers of the Confederate armed forces consisted mainly of white males with an average age between sixteen and twenty-eight.[citation needed] The Confederacy adopted conscription in 1862. Many thousands of slaves served as laborers, cooks, and pioneers. Some freed blacks and men of color served in local state militia units of the Confederacy, primarily in Louisiana and South Carolina, but they were used for "local defense, not combat."[64] Depleted by casualties and desertions, the military suffered chronic manpower shortages. In the spring of 1865 the Confederate Congress, influenced by the public support by General Lee, approved the recruitment of black infantry units. Contrary to Lee’s and Davis’ recommendations, the Congress refused “to guarantee the freedom of black volunteers.” No more than two hundred troops were ever raised.[65]

Military leaders

Military leaders of the Confederacy (with their state or country of birth and highest rank[66]) included:

- Robert E. Lee (Virginia) - General and General-in-Chief (1865)

- Albert Sidney Johnston (Kentucky) - General

- Joseph E. Johnston (Virginia) - General

- Braxton Bragg (North Carolina) - General

- P.G.T. Beauregard (Louisiana) - General

- Richard S. Ewell (Virginia) - Lieutenant General

- Samuel Cooper (New York) - General (Adjutant General and highest ranking general in the Army); not in combat

- James Longstreet (South Carolina) - Lieutenant General

- Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson (Virginia now West Virginia)- Lieutenant General

- John Hunt Morgan (Kentucky) - Brigadier General

- A.P. Hill (Virginia) - Lieutenant General

- John Bell Hood (Kentucky) - Lieutenant General

- Wade Hampton III (South Carolina) - Lieutenant General

- Nathan Bedford Forrest (Tennessee) - Lieutenant General

- John Singleton Mosby, the "Grey Ghost of the Confederacy" (Virginia) - Colonel

- J.E.B. Stuart (Virginia) - Major General

- Edward Porter Alexander (Georgia) - Brigadier General

- Franklin Buchanan (Maryland) - Admiral

- Raphael Semmes (Maryland) - Rear Admiral (Brigadier General)

- Josiah Tattnall (Georgia) - Commodore

- Stand Watie (Georgia) - Brigadier General (last to surrender)

- Leonidas Polk (North Carolina) - Lieutenant General

- Sterling Price (Virginia) - Major General

- Jubal Anderson Early (Virginia) - Lieutenant General

- Richard Taylor (Kentucky) - Lieutenant General (Son of U.S. President Zachary Taylor)

- Lloyd J. Beall (South Carolina) - Colonel - Commandant of the Confederate States Marine Corps

- William Lamb (Virginia) - Colonel - Commandant of Fort Fisher

- Stephen Dodson Ramseur (North Carolina) Major General

- Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac (France) Major General

- John Austin Wharton (Tennessee) Major General

- Thomas L. Rosser (Virginia) Major General

- Patrick Cleburne (Ireland) Brigadier General

Table of CSA states

See also

- Burr conspiracy

- Triangular Trade

- Golden Circle (Slavery)

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Southern United States

- History of the Southern United States

- Flags of the Confederate States of America

- Seal of the Confederate States of America

- Confederate States of America dollar

- Stamps and postal history of the Confederate States

- Confederados

- Confederate Patent Office

- United States presidential election, 1864

- 38th United States Congress

- For the 2004 motion picture, see C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America

Notes

- ^ Drew Gilpin Faust p. 59

- ^ McPherson pg. 232-233

- ^ The text of the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union.

- ^ The text of A Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union.

- ^ The text of Georgia's secession declaration.

- ^ The text of A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union.

- ^ McPherson pg. 244.The text of Alexander Stephens' "Cornerstone Speech".

- ^ Cooper pg. xv

- ^ Cooper pg. xiv

- ^ Coski pg. 23. The bracketed text was added by Coski.

- ^ The text of Benjamin Palmer's "Thanksgiving Sermon".

- ^ The Presbyterian position on slavery "Negro Slavery Unjustifiable".

- ^ Ta me go OK, August 2008

- ^ The text of South Carolina's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Mississippi's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Florida's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Alabama's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Georgia's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Louisiana's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Texas' Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Virginia's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ Virginia did not turn over its military to the Confederate States until June 8, 1861 and the Constitution of the Confederate States was ratified on June 19 1861.

- ^ The text of Arkansas' Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of North Carolina's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The text of Tennessee's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The Tennessee legislature ratified an agreement to enter a military league with the Confederate States on May 7, 1861. Tennessee voters approved the agreement on June 8, 1861.

- ^ The text of Missouri's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ The pro-Confederate politicians tried to meet in Neosho, Missouri, and then were driven out of the entire state.

- ^ The text of Kentucky's Ordinance of Secession.

- ^ Russellville Convention

- ^ a b Lincoln's proclamation calling for troops from the remaining states (bottom of page); Department of War details to States (top)

- ^ Alexander H. Stephens A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States (1870), Vol. 2, p. 36. 75 MB PDF file "I maintain that it was inaugurated and begun, though no blow had been struck, when the hostile fleet, styled the "Relief Squadron," with eleven ships, carrying two hundred and eighty-five guns and two thousand four hundred men, was sent out from New York and Norfolk, with orders from the authorities at Washington, to reinforce Fort Sumter peaceably, if permitted "but forcibly if they must."

- ^ Declaration by the People of the Cherokee Nation of the Causes Which Have Impelled Them to Unite Their Fortunes With Those of the Confederate States of America

- ^ ""Marx and Engels on the American Civil War", Army of the Cumberland and George H. Thomas source page

- ^ "Background of the Confederate States Constitution", The American Civil War Home Page

- ^ Davis p. 248

- ^ "Legal Materials on the Confederate States of America in the Schaffer Law Library", Albany Law School.

- ^ Records of District Courts of the United States, National Archives.

- ^ [Neely 11, 16]

- ^ Henry Blumenthal Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 32, No. 2. (May, 1966), pp. 152.

- ^ Henry Blumenthal Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 32, No. 2. (May, 1966), pg. 155

- ^ a b Henry Blumenthal Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 32, No. 2. (May, 1966), pg. 159

- ^ Stanley Lebergott Why the South Lost: Commercial Purpose in the Confederacy, 1861-1865 The Journal of American History, Vol. 70, No. 1. (Jun., 1983), pp. 61

- ^ International Slavery Museum, Liverpool, UK

- ^ See text of inscription on the Abraham Lincoln statue in Manchester, UK

- ^ Henry Blumenthal Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities pg. 157

- ^ ibid See articles footnote 20

- ^ Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, p. 1015.

- ^ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism's description of Kenner's diplomatic mission

- ^ Frank L. Owsley, State Rights in the Confederacy (Chicago, 1925),

- ^ Rable (1994) 257; however Wallace Hettle in The Peculiar Democracy: Southern Democrats in Peace and Civil War (2001) p. 158 says Owsley's "famous thesis... is overstated."

- ^ John Moretta; "Pendleton Murrah and States Rights in Civil War Texas," Civil War History, Vol. 45, 1999

- ^ Albert Burton Moore, Conscription and Conflict in the Confederacy. (1924) P. 295.

- ^ Rable (1994) 258-9

- ^ Rable (1994) p 265

- ^ William Seward to Charles Francis Adams, April 10, 1861 in Marion Mills Miller, Ed. Life And Works Of Abraham Lincoln (1907) Vol 6.

- ^ ibid

- ^ Moore, Frank, The Rebellion Record, Volume I, G.P. Putnam, 1861, Doc. 140, pages 195-197

- ^ a b Charles W. Ramsdell The Confederate Government and the Railroads The American Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Jul., 1917), p. 795

- ^ Mary Elizabeth Massey Ersatz in the Confederacy University of South Carolina Press, Columbia. 1952 p. 128

- ^ Charles W. Ramsdell The Confederate Government and the Railroads The American Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Jul., 1917), p. 809-810

- ^ Tariff of the Confederate States of America, May 21, 1861.

- ^ 1862blackCSN

- ^ Rubin pg. 104

- ^ Levine pg. 146-147

- ^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Confederate_States_of_America#flags

References

- Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Wilentz, Sean, The Rise of American Democracy, W.W. Norton & Co., ISBN 0-393-32921-6.

Bibliography

- Cooper, William J. Jr. Jefferson Davis, American. (2000)

- Coski, John. The Confederate Battle Flag. (2005)

- Current, Richard N., ed. Encyclopedia of the Confederacy (4 vol), 1993. 1900 pages, articles by scholars.

- Davis, William C. "A Government of Our Own". (1994) ISBN 0-8071-2177-0

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South. (1988)

- Faust, Patricia L. ed, Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War, 1986.

- Heidler, David S., et al. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War : A Political, Social, and Military History, 2002. 2400 pages (ISBN 0-393-04758-X)

- Levine, Bruce. Confederate Emancipation. (2006)

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom. (1988)

- Rubin, Sarah Anne. A Shattered Nation: The Rise & Fall of the Confederacy 1861-1868. (2005)

- Woodworth, Steven E. ed. The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research, 1996. 750 pages of historiography and bibliography

Economic and social history

see Economy of the Confederate States of America

- Black, Robert C., III. The Railroads of the Confederacy, 1988.

- Clinton, Catherine, and Silber, Nina, eds. Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War, 1992.

- Dabney, Virginius. Richmond: The Story of a City. Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8139-1274-1.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War, 1996.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South, 1988.

- Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865, 1995.

- Lentz, Perry Carlton. Our Missing Epic: A Study in the Novels about the American Civil War, 1970.

- Massey, Mary Elizabeth. Bonnet Brigades: American Women and the Civil War, 1966.

- Massey, Mary Elizabeth. Refugee Life in the Confederacy, 1964.

- Rable, George C. Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism, 1989.

- Ramsdell, Charles. Behind the Lines in the Southern Confederacy, 1994.

- Roark, James L. Masters without Slaves: Southern Planters in the Civil War and Reconstruction, 1977.

- Rubin, Anne Sarah. A Shattered Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Confederacy, 1861-1868, 2005. A cultural study of Confederates' self images.

- Thomas, Emory M. The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience, 1992.

- Wiley, Bell Irwin. Confederate Women, 1975.

- Wiley, Bell Irwin. The Plain People of the Confederacy, 1944.

- Woodward, C. Vann, ed. Mary Chesnut's Civil War, 1981.

Politics

- Alexander, Thomas B., and Beringer, Richard E. The Anatomy of the Confederate Congress: A Study of the Influences of Member Characteristics on Legislative Voting Behavior, 1861-1865, 1972.

- Boritt, Gabor S., et al, Why the Confederacy Lost, 1992.

- Cooper, William J, Jefferson Davis, American, 2000. Standard biography.

- Coulter, E. Merton. The Confederate States of America, 1861-1865, 1950.

- William C. Davis (2003). Look Away! A History of the Confederate States of America. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-86585-8.

- Eaton, Clement. A History of the Southern Confederacy, 1954.

- Eckenrode, H. J., Jefferson Davis: President of the South, 1923.

- Gallgher, Gary W., The Confederate War, 1999.

- Neely, Mark E., Jr., Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties, 1993.

- Rembert, W. Patrick. Jefferson Davis and His Cabinet, 1944.

- Rable, George C., The Confederate Republic: A Revolution against Politics, 1994.

- Roland, Charles P. The Confederacy, 1960. brief

- Thomas, Emory M. Confederate Nation: 1861-1865, 1979. Standard political-economic-social history

- Wakelyn, Jon L. Biographical Dictionary of the Confederacy Greenwood Press ISBN 0-8371-6124-X

- Williams, William M. Justice in Grey: A History of the Judicial System of the Confederate States of America, 1941.

- Yearns, Wilfred Buck. The Confederate Congress, 1960.

Primary sources

- Carter, Susan B., ed. The Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition (5 vols), 2006.

- Davis, Jefferson, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (2 vols), 1881.

- Harwell, Richard B., The Confederate Reader (1957)

- Jones, John B. A Rebel War Clerk's Diary at the Confederate States Capital, edited by Howard Swiggert, [1935] 1993. 2 vols.

- Richardson, James D., ed. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, Including the Diplomatic Correspondence 1861-1865, 2 volumes, 1906.

- Yearns, W. Buck and Barret, John G.,eds. North Carolina Civil War Documentary, 1980.

- Confederate official government documents major online collection of complete texts in HTML format, from U. of North Carolina

- Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865 (7 vols), 1904. Available online at the Library of Congress[1]

External links

- The McGavock Confederate Cemetery at Franklin, TN

- Confederate offices Index of Politicians by Office Held or Sought

- Civil War Research & Discussion Group -*Confederate States of Am. Army and Navy Uniforms, 1861

- The Countryman, 1862-1866, published weekly by Turnwold, Ga., edited by J.A. Turner

- The Federal and the Confederate Constitution Compared

- The Making of the Confederate Constitution, by A. L. Hull, 1905.

- Confederate Currency

- Photographs of the original Confederate Constitution and other Civil War documents owned by the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia Libraries.

- Photographic History of the Civil War, 10 vols., 1912.

- DocSouth: Documenting the American South - numerous online text, image, and audio collections.

- Confederate States of America: A Register of Its Records in the Library of Congress