Courage Under Fire

| Courage Under Fire | |

|---|---|

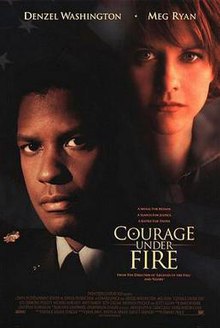

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Edward Zwick |

| Written by | Patrick Sheane Duncan |

| Produced by | John Davis Joseph M. Singer David T. Friendly |

| Starring | Denzel Washington Meg Ryan Lou Diamond Phillips Matt Damon Scott Glenn Michael Moriarty Bronson Pinchot Seth Gilliam |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Steven Rosenblum |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date | July 12, 1996 |

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $46 million[1] |

| Box office | $100,860,818 |

Courage Under Fire is a 1996 film directed by Edward Zwick, and starring Denzel Washington, Meg Ryan, Lou Diamond Phillips and Matt Damon.

Plot

Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Serling (Denzel Washington) was involved in a friendly fire incident in Al Bathra during the Gulf War. He was an M1 Abrams tank battalion commander who, during the nighttime confusion of Iraqi tanks infiltrating his unit's lines, gave the order to fire, destroying one of his own tanks and killing his friend Captain Boylar. The details were covered up (Boylar's parents were told that their son was killed by enemy fire), and Serling was shuffled off to a desk job.

Later, he is assigned to determine if Army Captain Karen Emma Walden (Meg Ryan) should be the first woman to receive (posthumously) the Medal of Honor for valor in combat. A Medevac Huey commander, she was sent to rescue the crew of a Black Hawk that had been shot down. Finding them under heavy fire from an Iraqi T-54 tank and infantry, her men dropped an auxiliary fuel bladder on the tank and ignited it with a flare gun. Shortly after, her helicopter was also hit and downed. The two crews were unable to join forces. The survivors were rescued the next day, but Walden had been killed.

At first, everything seems to be straightforward, but Serling begins to notice inconsistencies between the testimonies of the witnesses. Walden's co-pilot, Warrant Officer One A. Rady (Tim Guinee), praises Walden's character and performance, but was hit and rendered unconscious early on. Serling then sees Walden's medic, Specialist Ilario (Matt Damon), who also praises Walden; by his account, Walden was the one who came up with the idea of the improvised incendiary. Staff Sergeant Monfriez (Lou Diamond Phillips), however, tells Serling that Walden was a coward and that he was responsible for destroying the tank. The members of the other downed crew mention that they heard the distinctive sound of an M16 being used in the firefight during the rescue around the other helicopter, but Walden's crew denies firing one during the rescue, as theirs was out of ammunition. When Serling visits Walden's crew chief, Sergeant Altameyer (Seth Gilliam), who is dying of cancer in a hospital, Altameyer manages to get some words out, further confusing Serling, before self-medicating himself into unconsciousness.

Under pressure from the White House and his commander, Brigadier General Hershberg (Michael Moriarty), to wrap things up quickly, Serling leaks the story to newspaper reporter Tony Gartner (Scott Glenn) to prevent another cover up. When Serling puts pressure on Monfriez during a car ride, Monfriez forces him to get out of the vehicle at gunpoint, then commits suicide by driving into an oncoming train.

After finding an AWOL Ilario, Serling discovers that Monfriez wanted to escape under cover of darkness, which would have meant leaving Rady behind. Altameyer was ready to follow his lead and Ilario was wavering, but Walden refused to go along, resulting in an armed standoff with Monfriez. When an Iraqi infantryman appeared suddenly behind Monfriez, Walden fired at him. Mistakenly believing he was the target, Monfriez shot back and seriously wounded her. Walden, however, regained control of her men. The next morning, Walden stayed behind to cover their evacuation, firing the M16. Monfriez deliberately lied to the rescuers, telling them that she was dead so she would be left behind. Altameyer, injured and unable to say anything but "no!", was ignored. Ilario remains silent, as A-10s napalm the wreckage.

Serling presents his final report to Hershberg. Walden's young daughter receives the Medal of Honor in a White House ceremony. Later, Serling tearfully tells the Boylars the truth about the manner of their son's death and they forgive him for his role in it. In the last moments of the film, it is shown that Walden had transported Boylar's body away from the battlefield.

Cast

- Denzel Washington as Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Serling

- Meg Ryan as Captain Karen Emma Walden

- Lou Diamond Phillips as Staff Sergeant John Monfriez

- Matt Damon as Specialist Ilario

- Bronson Pinchot as Bruno, a White House aide

- Seth Gilliam as Sergeant Steven Altameyer

- Regina Taylor as Meredith Serling

- Michael Moriarty as Brigadier General Hershberg

- Zeljko Ivanek as Captain Ben Banacek

- Scott Glenn as Tony Gartner, a Washington Post reporter

- Tim Guinee as Warrant Officer One A. Rady

- Tim Ransom as Captain Boylar

- Sean Astin as Sergeant Patella

- Ned Vaughn as First Lieutenant Chelli

- Sean Patrick Thomas as Sergeant Thompson

- Manny Perez as Jenkins

- Ken Jenkins as Joel Walden

- Kathleen Widdoes as Geraldine Walden

- Christina Stojanovich as Anne Marie Walden

- Tom Schanley as Questioner

Reception

Box office

- U.S. domestic gross: US$ 59,031,057 [2]

- International: $41,829,761[2]

- Worldwide gross: $100,860,818[2]

The film opened #3 at the box office behind Independence Day and Phenomenon[3]

Critical response

The film received mostly positive reviews. As of January 14, 2013 the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 85% of critics gave the film a positive review based upon a sample of 53 reviews with an average rating of 7.3/10.[4] At the website Metacritic, which utilizes a normalized rating system, the film earned a generally favorable rating of 77/100 based on 19 mainstream critic reviews.[5]

The movie was commended by several critics. James Berardinelli of the website ReelReviews wrote that the film was, “As profound and intelligent as it is moving, and that makes this memorable motion picture one of 1996's best.”[6] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times spoke positively of the film saying that while the ending “…lays on the emotion a little heavily” the movie had been up until that point “…a fascinating emotional and logistical puzzle—almost a courtroom movie, with the desert as the courtroom.”[7]

Denzel Washington’s acting was specifically lauded as Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wrote, “In Washington's haunted eyes, in the stunning cinematography of Roger Deakins (Fargo) that plunges into the mad flare of combat, in the plot that deftly turns a whodunit into a meditation on character and in Zwick's persistent questioning of authority, Courage Under Fire honors its subject and its audience.”[8] Additionally Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle said that, “Denzel Washington is riveting.”[9]

Accolades

The film received no Academy Award, Golden Globe or BAFTA nominations. Denzel Washington was nominated for Best Actor at the 1996 Chicago Film Critics Association Awards, but lost to Billy Bob Thornton in Sling Blade.

Historical accuracy

The Medal of Honor had been awarded to a woman, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, an American Civil War doctor, but not for valor in combat. A White House aide played by Bronson Pinchot makes the distinction.

The Geneva Conventions permit military medical personnel to carry and use weapons to defend themselves and their patients.[10] (Taking offensive action would invalidate their status as protected non-combatants and would be considered perfidy.) In this respect, the portrayal of the helicopter crew was accurate in that the commanding officer, Captain Walden, carried a side-arm, while the two non-medical personnel in the helicopter (Monfriez, an infantryman, and Altameyer, the helicopter crew chief) were equipped with an M16 rifle and M249 SAW. Specialist Ilario, the crew's Combat Medic, was unarmed throughout the engagement. Based on these observations, no violation of the Geneva Convention was made by the fictional crew.

Production

The U.S. Department of Defense withdrew its cooperation for the film so the tanks Serling commanded early in the film were British Centurions shipped from Australia with sheet metal added to make them resemble M1A1 Abrams. These visually modified tanks were used to simulate the Abrams in several other motion pictures afterwards as well.

ROTC Cadets from Texas A&M University were extras in the background in some of the training camp scenes.

The Iraqi battle scenes were filmed at the Indian Cliffs Ranch, located just outside El Paso, Texas. Many of the props were left there and became a tourist attraction. The White House rose garden set was destroyed twice: once by a tornado, and once by a sandstorm.

In order to lose 40 pounds (18 kilograms) for the later scenes, Matt Damon went on a strict regimen of food deprivation and physical training. On Inside the Actors Studio, Damon said that the regimen consisted of six and a half miles of running in the morning and again at night, a diet of chicken breast, egg whites, and one plain baked potato per day, and a large amount of coffee and cigarettes. His health was affected to the extent that he had to have medical supervision for several months afterwards. His efforts, however, did not go unnoticed; director Francis Ford Coppola was so impressed by Damon's dedication to method acting that he offered him the leading role in The Rainmaker (1997). Steven Spielberg was also impressed by his performance, but thought he was too skinny and discounted him from casting considerations for Saving Private Ryan until he met Damon during the filming of Good Will Hunting when he was back at his normal weight.

References

- ^ Box office / business for Courage Under Fire (1996); imdb.com

- ^ a b c Courage Under Fire – Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information. The Numbers. Retrieved on 2013-05-11.

- ^ "July 12–14, 1996". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Courage Under Fire Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) [dead link] - ^ "Courage Under Fire Reviews". MetaCritic. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (July 1996). "Courage under Fire". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 12, 1996). "Courage Under Fire". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Travers, Peter (July 12, 1996). "Courage under Fire". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ Stack, Peter (July 12, 1996). "Fired-Up Over `Courage'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ ICRC databases on international humanitarian law. Icrc.org. Retrieved on 2013-05-11.

External links

- 1996 films

- American films

- 1990s drama films

- American war films

- Davis Entertainment films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Edward Zwick

- Films set in Iraq

- Gulf War fiction

- Films set in the United States

- Films shot in El Paso, Texas

- Gulf War films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Films shot in Connecticut

- Film scores by James Horner