Davidic line

| House of David בֵּית דָּוִד | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Kingdom of Israel and Judah (c. 1010 BCE–930 BCE) Kingdom of Judah (c. 930 BCE–587 BCE) |

| Place of origin | Tribe of Judah |

| Founder | David (traditional) |

| Final ruler | Zedekiah |

| Titles | |

| Estate(s) | Land of Israel |

The Davidic line refers to the descendants of Dawid ben Yishai, who established the House of David (Hebrew: בֵּית דָּוִד Bēt Dāwīḏ) in the Kingdom of Israel and Judah. In Judaism, it is based on texts from the Hebrew Bible, as well as on later Jewish traditions.

According to the biblical narrative, David of the Tribe of Judah engaged in a protracted conflict with Ish-bosheth of the Tribe of Benjamin after the latter succeeded his father Saul to become the second king of an amalgamated Israel and Judah. Amidst this struggle, God had sent his prophet Samuel to anoint David as the true king of the Israelites. Following Ish-bosheth's assassination at the hands of his own army captains, David officially acceded to the throne around 1010 BCE, replacing the House of Saul with his own and becoming the country's third king.[1][2] He was succeeded by his son Solomon, whose mother was Bathsheba. Solomon's death led to the rejection of the House of David by most of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, with only Judah and Benjamin remaining loyal: the dissenters chose Jeroboam as their monarch and formed the Kingdom of Israel in the north (Samaria); while the loyalists kept Solomon's son Rehoboam as their monarch and formed the Kingdom of Judah in the south (Judea). With the success of Jeroboam's Revolt having severed Israel's connection to the House of David, only the Judahite monarchs, except Athaliah, were part of the Davidic line.

In the aftermath of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem around 587 BCE, Solomon's Temple was destroyed and the Kingdom of Judah fell to the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Nearly 450 years later, the Hasmonean dynasty established the first independent Jewish kingdom since the Babylonian conquest, though it was not considered to be connected to the Davidic line nor to the Tribe of Judah.

In Jewish eschatology, the Messiah (מָשִׁיחַ) will be a Jewish king whose paternal bloodline traces to David. He is expected to rule over the Jewish people during the Messianic Age and in the world to come.[3][4][5]

Historicity

[edit]

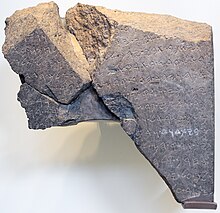

Very little is conclusively known about the House of David. The Tel Dan Stele mentions the death of the reigning king from "BYTDWD",[6] (interpreted as "House of David") and thus far is the only extrabiblical explicit mention of David himself. The stele is dated to circa 840 BCE; however, the name of the Davidic king is not totally preserved, as much of the stele has not survived since the 9th century BCE. All that remains of the name is the final syllable, the extremely common theophoric suffix -yahū. Because the stele coincides the death of the Davidic king with the death of [Jeho]ram, the king of the Kingdom of Samaria, scholars have reconstructed the second slain king as Ahaziah of Judah, the only king contemporary to Jehoram with a name ending in -yahū.[a]

The earliest unambiguously[b] attested king from the Davidic line is Uzziah, who reigned in the 8th century BCE, about 75 years after Ahaziah, who is named on bullae seals belonging to his servants Abijah and Shubnayahu.[7] Uzziah may also be mentioned in the annals of Tiglath-Pileser III; however, the texts are largely fragmentary.[8][c] Additionally, a tombstone dated to the Second Temple Period claiming to mark the grave (or, reburial) site of Uzziah, was discovered in a convent on the Mount of Olives in 1931, but there is no way of determining if the remains were genuinely Uzziah's as the stone had to have been carved more than 700 years after Uzziah died and was originally interred, and the tablet's provenance remains a mystery. A controversial artefact called the Jehoash Tablet recalls deeds performed by Jehoash of Judah, who reigned about 44 years before Uzziah; however, scholars are tensely divided on whether or not the inscription is genuine. After Uzziah, each successive king of Judah is attested to in some form, with the exception of Amon of Judah: Jotham, Uzziah's successor, is named on the seals of his own son and successor, Ahaz,[9] who ruled from 732 to 716 BCE. Hezekiah, Ahaz's son, is attested to by numerous royal seals[10][11] and Sennacherib's Annals;[12] Manasseh is recorded giving tribute to Esarhaddon;[13] Josiah has no relics explicitly naming him; however, seals belonging to his son Eliashib[14] and officials Nathan-melech[15][16] and Asaiah[17] have been discovered; and the kings Jehoahaz II, Jehoiakim, and Zedekiah are never explicitly named in historical records but are instead alluded to; however, Jeconiah is mentioned by name in Babylonian documents detailing the rations he and his sons were given while held prisoner during the Babylonian captivity.[18]

The origins of the dynasty, on the other hand, are shrouded in mystery. The Tel Dan Stele, as aforementioned, remains the only mention of David himself outside the Bible, and the historical reliability of the United Monarchy of Israel is archaeologically weak. The Stepped Stone Structure and Large Stone Structure in Jerusalem, assuming Eilat Mazar's contested stratigraphic dating of the structures to the Iron Age I is accurate, show that Jerusalem was at least somewhat populated in King David's time, and lends some credence to the biblical claim that Jerusalem was originally a Canaanite fortress; however, Jerusalem seems to have been barely developed until long after David's death,[19] bringing into question the possibility that it could have been the imperial capital described in the Bible. In David's time, the capital probably served as little more than a formidable citadel, and the Davidic "kingdom" was most likely closer to a loosely-confederated regional polity,[19] albeit a relatively substantial one. On the other hand, excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa[20] and Eglon,[21] as well as structures from Hazor, Gezer, Megiddo and other sites conventionally dated to the 10th century BCE, are interpreted by many scholars to show that Judah was capable of accommodating large-scale urban societies centuries before minimalist scholars claim,[22][23][24] and some have taken the physical archaeology of tenth-century Canaan as consistent with the former existence of a unified state on its territory,[25] as archaeological findings demonstrate substantial development and growth at several sites, plausibly related to the tenth century.[26] Even so, as for David and his immediate descendants themselves, the position of some scholars, as described by Israel Finkelstein and Neil Silberman, authors of The Bible Unearthed, espouses that David and Solomon may well be based on "certain historical kernels", and probably did exist in their own right, but their historical counterparts simply could not have ruled over a wealthy lavish empire as described in the Bible, and were more likely chieftains of a comparatively modest Israelite society in Judah and not regents over a kingdom proper.[27]

Kingdom of Israel and Judah

[edit]

According to the Tanakh, upon being chosen and becoming king, one was customarily anointed with holy oil poured on one's head. In David's case, this was done by the prophet Samuel.

Initially, David was king over the Tribe of Judah only and ruled from Hebron, but after seven and a half years, the other Israelite tribes, who found themselves leaderless after the death of Ish-bosheth, chose him to be their king as well.[28]

All subsequent kings in both the ancient first united Kingdom of Israel and the later Kingdom of Judah claimed direct descent from King David to validate their claim to the throne in order to rule over the Israelite tribes.

Division after Solomon's death

[edit]After the death of David's son, King Solomon, the ten northern tribes of the Kingdom of Israel rejected the Davidic line, refusing to accept Solomon's son, Rehoboam, and instead chose as king Jeroboam and formed the northern Kingdom of Israel. This kingdom was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BCE which exiled much of the Northern Kingdom population and ended its sovereign status. The bulk population of the Northern Kingdom of Israel was forced to relocate to Mesopotamia and mostly disappeared from history as The Ten Lost Tribes or intermixed with exiled Judean populations two centuries later, while the remaining Israelite peoples in Samaria highlands have become known as Samaritans during the classic era and to modern times.

The Exilarchate

[edit]Later rabbinical authorities granted the office of exilarch to family members that traced its patrilineal[29] descent from David, King of Israel. The highest official of Babylonian Jewry was the exilarch (Reish Galuta, "Head of the Diaspora"). Those who held the position traced their ancestry to the House of David in the male line.[29] The position holder was regarded as a king-in-waiting, residing in Babylonia in the Achaemenid Empire as well as during the classic era. The Seder Olam Zutta attributes the office to Zerubbabel, a member of the Davidic line, who is mentioned as one of the leaders of the Jewish community in the 6th century BC, holding the title of Achaemenid Governor of Yehud Medinata.

Hasmonean and Herodian periods

[edit]The Hasmoneans, also known as the Maccabees, established their own monarchy in Judea following their revolt against the Hellenistic Seleucid dynasty. The Hasmoneans were not considered connected to the Davidic line nor to the Tribe of Judah. The Levites had always been excluded from the Israelite monarchy, so when the Maccabees assumed the throne in order to rededicate the defiled Second Temple, a cardinal rule was broken. According to scholars within Orthodox Judaism, this is considered to have contributed to their downfall and the eventual downfall of Judea; internal strife allowing for Roman occupation and the violent installation of Herod the Great as client king over the Roman province of Judea; and the subsequent destruction of the Second Temple by the future Emperor Titus.

During the Hasmonean period, the Davidic line was largely excluded from the royal house in Judea, but some members had risen to prominence as religious and communal leaders. One of the most notable of those was Hillel the Elder, who moved to Judea from his birthplace in Babylon. His great-grandson Simeon ben Gamliel became one of the Jewish leaders during the First Jewish–Roman War.[30]

Middle Ages

[edit]The Exilarchate in the Sasanian Empire was briefly abolished as a result of a revolt by the Mar-Zutra II in the late 5th century CE, with his son Mar-Zutra III being denied the office and relocating to Tiberias, then within the Byzantine Empire. Mar Ahunai lived in the period succeeding Mar Zutra II, but for almost fifty years after the failed revolt he did not dare to appear in public, and it is not known whether even then (c. 550) he really acted as Exilarch. The names of Kafnai and his son Haninai, who were Exilarchs in the second half of the 6th century, have been preserved.

The Exilarchate in Mesopotamia was officially restored after the Arab conquest in the 7th century and continued to function during the early Caliphates. Exilarchs continued to be appointed until the 11th century, with some members of the Davidic line dispersing across the Islamic world. There are conflicting accounts of the fate of the Exilarch family in the 11th century; according to one version Hezekiah ben David, who was the last Exilarch and also the last Gaon, was imprisoned and tortured to death. Two of his sons fled to Al-Andalus, where they found refuge with Joseph, the son and successor of Samuel ibn Naghrillah. However, The Jewish Quarterly Review mentions that Hezekiah was liberated from prison, and became head of the academy, and is mentioned as such by a contemporary in 1046.[31] An unsuccessful attempt of David ben Daniel of the Davidic line to establish an Exilarchate in the Fatimid Caliphate failed and ended with his downfall in 1094.

In the 11th–15th century, families that descended from the Exilarchs that lived in the South of France (Narbonne and Provence) and in northern Iberian peninsula (Barcelona, Aragon and Castile) received the title "Nasi" in the communities and were called "free men". They had a special economic and social status in the Jewish community, and they were close to their respective governments, some serving as advisers and tax collectors/finance ministers.

These families had special rights in Narbonne, Barcelona, and Castile. They possessed real estate and received the title "Don" and de la Kblriih (De la Cavalleria). Among the families of the "Sons of the Free" are the families of Abravanel and Benveniste.

In his book, A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France, Arthur J. Zuckerman proposes a theory that from 768 to 900 CE a Jewish Princedom ruled by members of the Exilarchs existed in feudal France. However, this theory has been widely contested.[32] Descendants of the house of exilarchs were living in various places long after the office became extinct. The grandson of Hezekiah ben David through his eldest son David ben Chyzkia, Hiyya al-Daudi, died in 1154 in Castile according to Abraham ibn Daud and is the ancestor of the ibn Yahya family. Several families, as late as the 14th century, traced their descent back to Josiah, the brother of David ben Zakkai who had been banished to Chorasan (see the genealogies in [Lazarus 1890] pp. 180 et seq.). The descendants of the Karaite Exilarchs have been referred to above.

A number of Jewish families in the Iberian peninsula and within Mesopotamia continued to preserve the tradition of descent from Exilarchs in the Late Middle Ages, including the families of Abravanel, ibn Yahya and Ben-David. Several Ashkenazi scholars also claimed descent from King David. On his father's side, Rashi has been claimed to be a 33rd-generation descendant of Johanan HaSandlar, who was a fourth-generation descendant of Gamaliel, who was reputedly descended from the Davidic line.[33] Similarly Maimonides claimed 37 generations between him and Simeon ben Judah ha-Nasi, who was also a fourth-generation descendant of Gamaliel.[34] Meir Perels traced the ancestry of Judah Loew ben Bezalel to the Hai Gaon through Judah Loew's alleged great-great-grandfather Judah Leib the Elder and therefore also from the Davidic dynasty; however, this claim is widely disputed, by many scholars such as Otto Muneles.[35] Hai Gaon was the son of Sherira Gaon, who claimed descent from Rabbah b. Abuha, who belonged to the family of the exilarch, thereby claiming descent from the Davidic line. Sherira's son-in-law was Elijah ben Menahem HaZaken.[36][37] The patriarch of the Meisels family, Yitskhak Eizik Meisels, was an alleged 10th generation descendant of the Exilarch, Mar Ukba.[38] The Berduga family of Meknes claim paternal descent from the Exilarch, Bostanai.[39] The Jewish banking family Louis Cahen d'Anvers claimed descent from the Davidic Line[40] Rabbi Yosef Dayan, who is a modern-day claimant to the Davidic throne in Israel and the founder of the Monarchist party Malchut Israel, descends from the Dayan family of Aleppo, who paternally descend from Hasan ben Zakkai, the younger brother of the Exilarch David I (d. 940). One of Hasan's descendants Solomon ben Azariah ha-Nasi settled in Aleppo were the family became Dayan's (judges) of the city and thus adopted the surname Dayan.[41][42]

In Judaism

[edit]Eschatology

[edit]In Jewish eschatology, the term mashiach, or "Messiah", came to refer to a future Jewish king from the Davidic line, who is expected to be anointed with holy anointing oil and rule the Jewish people during the Messianic Age.[43][44][45] The Messiah is often referred to as "King Messiah", or, in Hebrew, מלך משיח (melekh mashiach), and, in Aramaic, malka meshiḥa.[46]

Orthodox views have generally held that the Messiah will be a patrilineal descendant of King David,[47] and will gather the Jews back into the Land of Israel, usher in an era of peace, build the Third Temple, father a male heir, re-institute the Sanhedrin, and so on. Jewish tradition alludes to two redeemers, both of whom are called mashiach and are involved in ushering in the Messianic age: Mashiach ben David; and Mashiach ben Yosef. In general, the term Messiah unqualified refers to Mashiach ben David (Messiah, son of David).[43][44]

Modern legacy

[edit]In 2012, The Jerusalem Post reported that philanthropist Susan Roth created Davidic Dynasty as subsidiary of her Eshet Chayil Foundation, dedicated to finding, databasing, and connecting Davidic descendants and running the King David Legacy Center in Jerusalem.[48] In 2020, Roth chose Brando Crawford, a descendant from both grandfathers, to represent the organization internationally.[49][50] The King David Legacy Center has seen support from Haredi Jews in Jerusalem.[51]

In other Abrahamic religions

[edit]Christianity

[edit]In the Christian interpretation the "Davidic covenant" of a Davidic line in 2 Samuel 7 is understood in various ways, traditionally referring to the genealogies of Jesus in the New Testament. One Christian interpretation of the Davidic line counts the line as continuing to Jesus son of Joseph, according to the genealogies which are written in Matthew 1:1-16 descendants of Solomon and Luke 3:23-38 descendants of Nathan son of David through the line of Mary.

Because Jews have historically believed that the Messiah will be a male-line descendant of David, the lineage of Jesus is sometimes cited as a reason why Jews do not believe that he was the Messiah. As the proposed son of God, he could not have been a male descendant of David because according to the genealogy of his earthly parents, Mary and Joseph, he did not have the proper lineage, because he would not have been a male descendant of Mary, and Joseph, who was a descendant of Jeconiah, because Jeconiah's descendants are explicitly barred from ever ruling Israel by God.[52]

Another Christian interpretation emphasizes the minor, non-royal, line of David through Solomon's brother Nathan as it is recorded in the Gospel of Luke chapter 3 (entirely undocumented in the Hebrew Bible), which is often understood to be the family tree of Mary's father. A widely spread traditional Christian interpretation relates the non-continuation of the main Davidic line from Solomon to the godlessness of the line of Jehoiachin which started in the early 500s BC, when Jeremiah cursed the main branch of the Solomonic line, by saying that no descendant of "[Je]Coniah" would ever reign on the throne of Israel again (Jeremiah 22:30).[53] Some Christian commentators also believe that this same "curse" is the reason why Zerubbabel, the rightful Solomonic king during the time of Nehemiah, was not given a kingship under the Persian empire.[54]

The Tree of Jesse (a reference to David's father) is a traditional Christian artistic representation of Jesus' genealogical connection to David.

Islam

[edit]The Quran mentions the House of David once: "Work, O family of David, in gratitude. And few of My servants are grateful."[55] and mentions David himself sixteen times.

According to some Islamic sources, some of the Jewish settlers in Arabia were of the Davidic line, Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi recorded: "A Jewish man from the Davidic line entered Medina and found the people in deep sorrow. He enquired the people, 'What is wrong?' Some of the people replied: Prophet Muhammad passed away".[56]

See also

[edit]- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- Abravanel family, a Sephardic Jewish family claiming descent from David

- Bagrationi dynasty, a Georgian dynasty claiming descent from David

- Solomonic dynasty, an Ethiopian dynasty claiming descent from David's son Solomon

- Tree of Jesse, a Christian artistic depiction of Jesus' family tree beginning with David's father Jesse

References

[edit]- ^ Carr, David M. (2011). An Introduction to the Old Testament: Sacred Texts and Imperial Contexts of the Hebrew Bible. John Wiley & Sons. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-44435623-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Falk, Avner (1996). A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-83863660-2. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Schochet, Rabbi Prof. Dr. Jacob Immanuel. "Moshiach ben Yossef". Tutorial. moshiach.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Blidstein, Prof. Dr. Gerald J. "Messiah in Rabbinic Thought". MESSIAH. Jewish Virtual Library and Encyclopaedia Judaica 2008 The Gale Group. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph. "The Messiah". The Jewish Virtual Library Jewish Literacy. NY: William Morrow and Co., 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Pioske 2015, p. 180.

- ^ Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals. N. Avigad and B. Sass. Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1997, nos. 4 and 3 respectively; Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200–539 B.C.E. Lawrence J. Mykytiuk. SBL Academia Biblica 12. Atlanta, 2004, 153–59, 219.

- ^ Haydn, Howell M. Azariah of Judah and Tiglath-Pileser III in Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1909), pp. 182–199

- ^ Deutsch, Robert. "First Impression: What We Learn from King Ahaz's Seal Archived 4 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine". Biblical Archaeology Review, July 1998, pp. 54–56, 62

- ^ Heilpern, Will (4 December 2015). "Biblical King's seal discovered in dump site". CNN. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Cross, Frank Moore (March–April 1999). "King Hezekiah's Seal Bears Phoenician Imagery". Biblical Archaeology Review.

- ^ Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, pp. 287–288

- ^ Oppenheim, A. L. in Pritchard 1969, p. 291

- ^ Albright, W. F. in Pritchard 1969, p. 569

- ^ Weiss, Bari.The Story Behind a 2,600-Year-Old Seal Who was Natan-Melech, the king's servant? New York Times. March 30, 2019

- ^ 2,600-year old seal discovered in City of David. Jerusalem Post. April 1, 2019

- ^ Heltzer, Michael, THE SEAL OF ˓AŚAYĀHŪ. In Hallo, 2000, Vol. II p. 204

- ^ James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969) 308.

- ^ a b Mazar, Amihai. "Archaeology and the Biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy". One God – One Cult – One Nation. Archaeological and Biblical Perspectives, Edited by Reinhard G. Kratz and Hermann Spieckermann in Collaboration with Björn Corzilius and Tanja Pilger, (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 405). Berlin/ New York: 29–58. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Garfinkel, Yossi; Ganor, Sa'ar; Hasel, Michael (19 April 2012). "Journal 124: Khirbat Qeiyafa preliminary report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "Proof of King David? Not yet. But riveting site shores up roots of Israelite era". Times of Israel. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Halpern, Baruch (2017). "The United Monarchy: David between Saul and Solomon". In Ebeling, Jennie R.; Wright, J. Edward; Elliott, Mark Adam; Flesher, Paul V. McCracken (eds.). The Old Testament in Archaeology and History. Baylor University Press. pp. 337–62. ISBN 978-1-4813-0743-7.

- ^ Johnson, Benjamin J. M. (2021). "Israel at the time of the united monarchy". In Dell, Katharine J. (ed.). The Biblical World (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 498–519. ISBN 978-1-317-39255-2.

- ^ Dever, William G. (2021). "Solomon, Scripture, and Science: The Rise of the Judahite State in the 10th Century BCE". Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. 1: 102–125. doi:10.52486/01.00001.4.

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-80280-396-2.

- ^ Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East, c. 3000-330 BC, Band 1. New York: Routledge. p. 438. ISBN 978-0-41516-762-8.

- ^ ———; Silberman, Neil Asher (2006). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-4362-9. p. 20

- ^ Mandel, David. Who's Who in the Jewish Bible. Jewish Publication Society, 1 Jan 2010, p. 85

- ^ a b Max A Margolis and Alexander Marx, A History of the Jewish People (1927), p. 235.

- ^ Wilhelm Bacher, Jacob Zallel Lauterbach (1906). "Simeon II. (Ben Gamaliel I.)", Jewish Encyclopedia. N.b.: the Jewish Encyclopedia speaks of "his grandfather Hillel", but the sequence was Hillel the Elder-Simeon ben Hillel-Gamaliel the Elder-Simeon ben Gamliel, thus great-grandson is correct.

- ^ Jewish Quarterly Review, hereafter "J. Q. R.", xv. 80.

- ^ Zuckerman, Arthur J. (1972). A Jewish princedom in feudal France, 768-900. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03298-6. OCLC 333768.

- ^ "Rabbi Yehiel Ben Shlomo Heilprin - (Circa 5420-5506; 1660-1746)". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Early Years". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ See The Maharal of Prague's Descent from King David, by Chaim Freedman, published in Avotaynu Vol 22 No 1, Spring 2006

- ^ "SHERIRA B. ḤANINA - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "HAI BEN SHERIRA - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Meizels family tree" (PDF). Davidicdynasty.org.

- ^ Bar-Asher, Moshe (1 October 2010). "Berdugo Family". Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World.

- ^ "Jews of Turkey Archives • Point of No Return". Point of No Return.

- ^ "Dayyan | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Harel, Yaron (1 October 2010). "Dayan Family". Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World.

- ^ a b Schochet, Jacob Immanuel. "Moshiach ben Yossef". Tutorial. Moshiach.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ a b Blidstein, Prof. Dr. Gerald J. "Messiah in Rabbinic Thought". MESSIAH. Jewish Virtual Library and Encyclopaedia Judaica 2008 The Gale Group. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph (1991). "The Messiah". William Morrow and Co. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Flusser, David. "Second Temple Period". Messiah. Encyclopaedia Judaica 2008 The Gale Group. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ See Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan: "The Real Messiah A Jewish Response to Missionaries" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Are you a descendant of the House of David?". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Leadership". Davidic Dynasty is dedicated to uniting the Jewish descendants of King David. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Twersky, David (10 November 2008). "We Are Family: King David's Descendants Gather for 'Reunion'". The Forward. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Grapevine: Yes, Prime Minister…". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ This is what the LORD says: 'Record this man as if he is childless, a man who will not prosper in his lifetime, for none of his offspring will prosper, none of them will sit on the throne of David or rule in Judah anymore.— Jeremiah 22:30, NIV

- ^ H. Wayne House Israel: Land and the People 1998 114 "And yet, Judah has also been without a king of the Solomonic line since the Babylonian exile. Because of Jeremiah's curse on Jehoiachin (Coniah) in the early 500s BC (Jer. 22:30), the high priests of Israel, while serving as the ..."

- ^ Warren W. Wiersbe -The Wiersbe Bible Commentary: The Complete Old Testament - 2007 p. 1497 "Zerubbabel was the grandson of King Jehoiachin (Jeconiah, Matt. 1:12; Coniah, Jer. 22:24, 28), and therefore of the royal line of David. But instead of wearing a crown and sitting on a throne, Zerubbabel was the humble governor of a ..."

- ^ Quran 34:13

- ^ Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi, Bihār al-Anwār, Dar Al-Rida Publication, Beirut, (1983), volume 30 page 99

- Sources

- Pioske, Daniel (2015). David's Jerusalem: Between Memory and History. Routledge Studies in Religion. Vol. 45. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317548911.

- The Holy Bible: 1611 Edition (Thos. Nelson, 1993)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Jehoram's reign in Israel saw three kings of Judah — Jehoshaphat, his son Jehoram of Judah, and his son, Ahaziah

- ^ 'Unambiguous' as Ahaziah's name on the Tel Dan Stele is incomplete, and there is no explicit confirmation that the apical ancestor David of Bayt-David was a king

- ^ The name in the annals is Azariah, not "Uzziah". While Uzziah is called "Azariah" several times in the Bible, scholars consider this to be the result of a later scribal error. Thus it is unlikely that Tiglath-Pileser's scribes would have used this name to refer to Uzziah.

External links

[edit]- "King David Dynasty"

- Jewish Encyclopedia.com: "Exilarchs"

- A genealogy of the Exilarchs: "From Judah to Bustanai"

- Davidic Dynasty

- House of David Judaica

- Rabbinic Sources and Seder Olam Zuta: "Seder Olam Zuta" & "Rav-SIG"