Death of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler killed himself by gunshot on 30 April 1945 in his Führerbunker in Berlin.[a][b][c] His wife Eva Braun committed suicide with him by taking cyanide.[d] That afternoon, in accordance with Hitler's prior instructions, their remains were carried up the stairs through the bunker's emergency exit, doused in petrol, and set alight in the Reich Chancellery garden outside the bunker.[1] Records in the Soviet archives show that their burnt remains were recovered and interred in successive locations[e] until 1970, when they were again exhumed, cremated, and the ashes scattered.[f]

Accounts differ as to the cause of death; one states that he died by poison only[g] and another that he died by a self-inflicted gunshot while biting down on a cyanide capsule.[h] Contemporary historians have rejected these accounts as being either Soviet propaganda[i][j] or an attempted compromise in order to reconcile the different conclusions.[h][k] One eyewitness recorded that the body showed signs of having been shot through the mouth, but this has been proven unlikely.[l][m] There is also controversy regarding the authenticity of skull and jaw fragments which were recovered.[n][o] In 2009, American researchers performed DNA tests on a skull Soviet officials had long believed to be that of Hitler. The tests and examination revealed that the skull was actually that of a woman less than 40 years old. The jaw fragments which had been recovered were not tested.[2][3][p]

Preceding events

By early 1945, Germany's military situation was on the verge of total collapse. Poland had fallen to the advancing Soviet forces, who were, by then, preparing to cross the Oder between Küstrin and Frankfurt with the objective of capturing Berlin, 82 kilometres (51 mi) to the west.[4] German forces had recently lost to the Allies in the Ardennes Offensive, with British and Canadian forces crossing the Rhine into the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr.[5] American forces in the south had captured Lorraine and were advancing towards Mainz, Mannheim, and the Rhine.[5] In Italy, German forces were withdrawing north, as they were pressed by the American and Commonwealth forces as part of the Spring Offensive to advance across the Po and into the foothills of the Alps.[6] In parallel to the military actions, the Allies had met at Yalta between 4–11 February to discuss the conclusion of the war in Europe.[7]

Hitler, presiding over a rapidly disintegrating Third Reich, retreated to his Führerbunker in Berlin on 16 January 1945. To the Nazi leadership, it was clear that the battle for Berlin would be the final battle of the war in Europe.[8] Some 325,000 soldiers of Germany's Army Group B were surrounded and captured on 18 April, leaving the path open for American forces to reach Berlin. By 11 April the Americans crossed the Elbe, 100 kilometres (62 mi) to the west of the city.[9] On 16 April, Soviet forces to the east crossed the Oder and commenced the battle for the Seelow Heights, the last major defensive line protecting Berlin on that side.[10] By 19 April the Germans were in full retreat from Seelow Heights, leaving no front line. Berlin was bombarded by Soviet artillery for the first time on 20 April (Hitler's birthday). By the evening of 21 April, Red Army tanks reached the outskirts of the city.[11]

At the afternoon situation conference on 22 April, Hitler suffered a total nervous collapse when he was informed that the orders he had issued the previous day for SS-General Felix Steiner's Army Detachment Steiner to move to the rescue of Berlin had not been obeyed.[12] Hitler launched a tirade against the treachery and incompetence of his commanders, culminating in a declaration—for the first time—that the war was lost. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the end, and then shoot himself.[13] Later that day he asked SS physician Dr. Werner Haase about the most reliable method of suicide. Haase suggested the "pistol-and-poison method" of combining a dose of cyanide with a gunshot to the head.[14] When head of the Luftwaffe Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring learned about this, he sent a telegram to Hitler asking for permission to take over the leadership of the Reich in accordance with Hitler's 1941 decree naming Göring his successor.[15] Hitler's influential secretary, Martin Bormann, convinced Hitler that Göring was threatening a coup.[16] In response, Hitler informed Göring that he would be executed unless he resigned all of his posts. Later that day, he sacked Göring from all of his offices and ordered his arrest.[17]

By 27 April, Berlin was cut off from the rest of Germany. Secure radio communications with defending units had been lost; the command staff in the bunker had to depend on telephone lines for passing instructions and orders and on public radio for news and information.[18] On 28 April, a BBC report originating from Reuters was picked up; a copy of the message was given to Hitler.[19] The report stated that Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had offered to surrender to the western Allies; the offer had been declined. Himmler had implied to the Allies that he had the authority to negotiate a surrender; Hitler considered this treason. During the afternoon his anger and bitterness escalated into a rage against Himmler.[20] Hitler ordered Himmler's arrest and had Hermann Fegelein (Himmler's SS representative at Hitler's headquarters in Berlin) shot.[21]

By this time, the Red Army had advanced to the Potsdamerplatz, and all indications were that they were preparing to storm the Chancellery. This report, combined with Himmler's treachery, prompted Hitler to make the last decisions of his life.[22] After midnight on 29 April, Hitler married Eva Braun in a small civil ceremony in a map room within the Führerbunker.[q] Afterwards Hitler hosted a modest wedding breakfast with his new wife. Hitler then took secretary Traudl Junge to another room and dictated his last will and testament. He signed these documents at 04:00 and then retired to bed (some sources say Hitler dictated the last will and testament immediately before the wedding, but all sources agree on the timing of the signing).[r][s]

During the course of 29 April, Hitler learned of the death of his ally, Benito Mussolini, who had been executed by Italian partisans. Mussolini's body and that of his mistress, Clara Petacci, had been strung up by their heels. The bodies were later cut down and thrown in the gutter, where vengeful Italians reviled them. It is probable that these events strengthened Hitler's resolve not to allow himself or his wife to be made "a spectacle of", as he had earlier recorded in his Testament.[23] That afternoon, Hitler expressed doubts about the cyanide capsules he had received through Himmler's SS.[24] To verify the capsules' potency, Hitler ordered Dr. Werner Haase to test one on his dog Blondi, who died as a result.[25]

Suicide

Hitler and Braun lived together as husband and wife in the bunker for fewer than 40 hours. By 01:00 on 30 April, General Wilhelm Keitel had reported that all forces which Hitler had been depending on to rescue Berlin had either been encircled or forced onto the defensive.[26] Late in the morning of 30 April, with the Soviets less than 500 metres (1,600 ft) from the bunker, Hitler had a meeting with General Helmuth Weidling, commander of the Berlin Defence Area, who told him that the garrison would probably run out of ammunition that night and that the fighting in Berlin would inevitably come to an end within the next 24 hours.[26] Weidling asked Hitler for permission for a breakout, a request he had made unsuccessfully before. Hitler did not answer, and Weidling went back to his headquarters in the Bendlerblock. At about 13:00 he received Hitler's permission to try a breakout that night.[27] Hitler, two secretaries, and his personal cook then had lunch, after which Hitler and Braun said farewell to members of the Führerbunker staff and fellow occupants, including Bormann, Joseph Goebbels and his family, the secretaries, and several military officers. At around 14:30 Adolf and Eva Hitler went into Hitler's personal study.[27]

Several witnesses later reported hearing a loud gunshot at around 15:30. After waiting a few minutes, Hitler's valet, Heinz Linge, with Bormann at his side, opened the study door.[28] Linge later stated he immediately noted a scent of burnt almonds, a common observation made in the presence of prussic acid, the aqueous form of hydrogen cyanide.[28] Hitler's adjutant, SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Günsche, entered the study and found the lifeless bodies on the sofa. Eva, with her legs drawn up, was to Hitler's left and slumped away from him. Günsche stated that Hitler "... sat ... sunken over, with blood dripping out of his right temple. He had shot himself with his own pistol, a Walther PPK 7.65".[29][28][30] The gun lay at his feet[28] and according to SS-Oberscharführer Rochus Misch, Hitler's head was lying on the table in front of him.[31] Blood dripping from Hitler's right temple and chin had made a large stain on the right arm of the sofa and was pooling on the carpet. According to Linge, Eva's body had no visible physical wounds, and her face showed how she had died—cyanide poisoning.[t] Günsche and SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke stated "unequivocally" that all outsiders and those performing duties and work in the bunker "did not have any access" to Hitler's private living quarters during the time of death (between 15:00 and 16:00).[32]

Günsche left the study and announced that the Führer was dead. The two bodies were carried up the stairs to ground level and through the bunker's emergency exit to the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were doused with petrol.[33] An eyewitness, Rochus Misch, reported someone shouting, "Hurry upstairs, they're burning the boss!"[31] After the first attempts to ignite the petrol did not work, Linge went back inside the bunker and returned with a thick roll of papers. Bormann lit the papers and threw the torch onto the bodies. As the two corpses caught fire, a small group, including Bormann, Günsche, Linge, Goebbels, Erich Kempka, Peter Högl, Ewald Lindloff, and Hans Reisser, raised their arms in salute as they stood just inside the bunker doorway.[33][34]

At around 16:15, Linge ordered SS-Untersturmführer Heinz Krüger and SS-Oberscharführer Werner Schwiedel to roll up the rug in Hitler's study to burn it. Schwiedel later stated that upon entering the study, he saw a pool of blood the size of a "large dinner plate" by the arm-rest of the sofa. Noticing a spent cartridge case, he bent down and picked it up from where it lay on the rug about 1 mm from a 7.65 pistol.[35] The two men removed the blood-stained rug, carried it up the stairs and outside to the Chancellery garden. There the rug was placed on the ground and burned.[36]

On and off during the afternoon, the Soviets shelled the area in and around the Reich Chancellery. SS guards brought over additional cans of petrol to further burn the corpses. Linge later noted the fire did not completely destroy the remains, as the corpses were being burned in the open, where the distribution of heat varies.[37] The burning of the corpses lasted from 16:00 to 18:30.[38] The remains were covered up in a shallow bomb crater at around 18:30 by Lindloff and Reisser.[39]

Aftermath

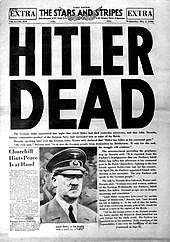

The first inkling to the outside world that Hitler was dead came from the Germans themselves. On 1 May the radio station Reichssender Hamburg interrupted their normal program to announce that an important broadcast would soon be made. After dramatic funeral music by Wagner and Bruckner, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz (appointed as Hitler's successor in his will) announced that Hitler was dead.[40] Dönitz called upon the German people to mourn their Führer, who died a hero defending the capital of the Reich.[41] Hoping to save the army and the nation by negotiating a partial surrender to the British and Americans, Dönitz authorized a fighting withdrawal to the west. His tactic was somewhat successful: it enabled about 1.8 million German soldiers to avoid capture by the Soviets, but it came at a high cost in bloodshed, as troops continued to fight until 8 May.[42]

On the morning of 1 May, thirteen hours after the event, Stalin was informed of Hitler's suicide.[43] General Hans Krebs had given this information to Soviet General Vasily Chuikov when they met at 04:00 on 1 May, when the Germans attempted to negotiate acceptable surrender terms.[44][45] Stalin demanded unconditional surrender and asked for confirmation that Hitler was dead. He wanted Hitler's corpse found.[46] In the early morning hours of 2 May, the Soviets captured the Reich Chancellery.[47] Down in the Führerbunker, General Krebs and General Wilhelm Burgdorf committed suicide by gunshot to the head.[48]

Later on 2 May, the remains of Hitler, Braun, and two dogs (thought to be Blondi and her offspring, Wulf) were discovered in a shell crater by a unit of the Red Army intelligence agency SMERSH tasked with finding Hitler's body. Stalin was wary of believing Hitler was dead, and restricted the release of information to the public.[49][50] The remains of Hitler and Braun were repeatedly buried and exhumed by SMERSH during the unit's relocation from Berlin to a new facility in Magdeburg. The bodies, along with the charred remains of propaganda minister Goebbels, his wife Magda, and their six children, were buried in an unmarked grave beneath a paved section of the front courtyard. The location was kept secret.[51]

For politically motivated reasons, various versions of Hitler's fate were presented by the Soviet Union.[52][53] In the years immediately following 1945, the Soviets maintained Hitler was not dead, but had fled and was being shielded by the former western allies.[52] This worked for a time to create doubt among western authorities. The chief of the U.S. trial counsel at Nuremberg, Thomas J. Dodd, said: "No one can say he is dead." When President Harry S. Truman asked Stalin at the Potsdam Conference in August 1945 whether or not Hitler was dead, Stalin replied bluntly, "No". But by 11 May 1945, the Soviets had already confirmed through Hitler's dentist, Hugo Blaschke, dental assistant Käthe Heusermann and dental technician Fritz Echtmann that the dental remains found were Hitler's and Braun's.[54][55] In November 1945, Dick White, then head of counter-intelligence in the British sector of Berlin (and later head of MI5 and MI6 in succession), had their agent Hugh Trevor-Roper investigate the matter to counter the Soviet claims. His findings were written in a report and published in book form in 1947.[56]

In May 1946, SMERSH agents recovered from the crater where Hitler was buried two burned skull fragments with gunshot damage. These remains were apparently forgotten in the Russian State Archives until 1993, when they were re-found.[57] In 2009 DNA and forensic tests were performed on the skull fragment, which Soviet officials had long believed to be Hitler's. According to the American researchers, the tests revealed that the skull was actually that of a woman and the examination of the sutures where the skull plates come together placed her age at less than 40 years old. The jaw fragments which had been recovered in May 1945 were not tested.[2][3]

In 1969, Soviet journalist Lev Bezymensky's book on the death of Hitler was published in the West. It included the SMERSH autopsy report, but because of the earlier disinformation attempts, western historians thought it untrustworthy.[58]

In 1970, the SMERSH facility, by then controlled by the KGB, was scheduled to be handed over to the East German government. Fearing that a known Hitler burial site might become a Neo-Nazi shrine, KGB director Yuri Andropov authorised an operation to destroy the remains that had been buried in Magdeburg on 21 February 1946.[59] A Soviet KGB team was given detailed burial charts. On 4 April 1970 they secretly exhumed five wooden boxes containing the remains of "10 or 11 bodies ... in an advanced state of decay". The remains were thoroughly burned and crushed, after which the ashes were thrown into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe.[60][u]

According to Ian Kershaw the corpses of Braun and Hitler were already thoroughly burned when the Red Army found them, and only a lower jaw with dental work could be identified as Hitler's remains.[55]

Gallery

-

Joseph Goebbels, his wife Magda, and their six children. Standing in the back is Goebbels' stepson, Harald Quandt, the sole family member to survive the war.

-

Hitler (right) visiting Berlin defenders in early April 1945 with Hermann Göring (centre) and the Chief of the OKW Field Marshal Keitel (partially hidden)

-

Heinz Linge, Hitler's valet, was one of the first people into Hitler's study after the suicide.

-

Churchill sits on a damaged chair from the Führerbunker in July 1945.

See also

Notes

- ^ "... Günsche stated he entered the study to inspect the bodies, and observed Hitler ... sat ... sunken over, with blood dripping out of his right temple. He had shot himself with his own pistol, a PPK 7.65." (Fischer 2008, p. 47).

- ^ "... Blood dripped from a bullet hole in his right temple ..."(Kershaw 2008, p. 955).

- ^ "...30 April ... During the afternoon Hitler shot himself..." (MI5 staff 2011).

- ^ "... her lips puckered from the poison." (Beevor 2002, p. 359).

- ^ "... [the bodies] were deposited initially in an unmarked grave in a forest far to the west of Berlin, reburied in 1946 in a plot of land in Magdeberg." (Kershaw 2008, p. 958).

- ^ "In 1970 the Kremlin finally disposed of the body in absolute secrecy ... body ... was exhumed and burned." (Beevor 2002, p. 431).

- ^ "... both committing suicide by biting their cyanide ampoules." (Erickson 1983, p. 606).

- ^ a b "... we have a fair answer ... to the version of ... Russian author Lev Bezymenski ... Hitler did shoot himself and did bite into the cyanide capsule, just as Professor Haase had clearly and repeatedly instructed ... " (O'Donnell 2001, pp. 322–323)

- ^ "... New versions of Hitler's fate were presented by the Soviet Union according to the political needs of the moment ..." (Eberle & Uhl 2005, p. 288).

- ^ "The intentionally misleading account of Hitler's death by cyanide poisoning put about by Soviet historians ... can be dismissed."(Kershaw 2001, p. 1037).

- ^ "... most Soviet accounts have held that Hitler also [Hitler and Eva Braun] ended his life by poison ... there are contradictions in the Soviet story ... these contradictions tend to indicate that the Soviet version of Hitler's suicide has a political colouration."(Fest 1974, p. 749).

- ^ "Axmann elaborated on his testimony when questioned about his "assumption" that Hitler had shot himself through the mouth."(Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 157).

- ^ "... the version involving a 'shot in the mouth' with secondary injuries to the temples must be rejected ... the majority of witnesses saw an entry wound in the temple.. according to all witnesses there was no injury to the back of the head." (Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 166).

- ^ "... the only thing to remain of Hitler was a gold bridge with porcelain facets from his upper jaw and the lower jawbone with some teeth and two bridges." (Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 225).

- ^ "Hitler's jaws ... had been retained by SMERSH, while the NKVD kept the cranium." (Beevor 2002, p. 431)

- ^ "Deep in the Lubyanka, headquarters of Russia's secret police, a fragment of Hitler's jaw is preserved as a trophy of the Red Army's victory over Nazi Germany. A fragment of skull with a bullet hole lies in the State Archive". (Halpin & Boyes 2009).

- ^ "In the small hours of 28–29 April ... " (MI5 staff 2011).

- ^ Using sources available to Trevor Roper (a World War II MI5 agent and historian/author of The Last Days of Hitler), MI5 records the marriage as taking place after Hitler had dictated the last will and testament. (MI5 staff 2011).

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 343 records the marriage as taking place before Hitler had dictated the last will and testament.

- ^ "Cyanide poisoning. Its 'bite' was marked in her features." (Linge 2009, p. 199).

- ^ Beevor states that "... the ashes were flushed into the town [Magdeberg] sewage system." (Beevor 2002, p. 431).

References

Citations

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 956.

- ^ a b CNN staff 2009. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCNN_staff2009 (help)

- ^ a b Goñi 2009.

- ^ Horrabin 1946, Vol. X, p. 51.

- ^ a b Horrabin 1946, Vol. X, p. 53.

- ^ Horrabin 1946, Vol. X, p. 43.

- ^ Bellamy 2007, p. 648.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 139.

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 1105.

- ^ Beevor 2002, pp. 209–217.

- ^ Beevor 2002, pp. 255–256, 262.

- ^ Erickson 1983, p. 586.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 275.

- ^ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 230, 323.

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 1116.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 289.

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 1118.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 323.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 943.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 943–946.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 946–947.

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 1194.

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 1131.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 951–952.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 952.

- ^ a b Erickson 1983, pp. 603–604.

- ^ a b Beevor 2002, p. 358.

- ^ a b c d Linge 2009, p. 199.

- ^ Fischer 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, pp. 160–182.

- ^ a b Rosenberg 2009.

- ^ Fischer 2008, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Linge 2009, p. 200.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, pp. 197, 198.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 162.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, pp. 162, 175.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 211.

- ^ Joachimsthaler 1999, pp. 217–220.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 381.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 959.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 961–963.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 368.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 367.

- ^ Eberle & Uhl 2005, p. 280.

- ^ Eberle & Uhl 2005, pp. 280, 281.

- ^ Beevor 2002, pp. 387, 388.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 387.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, pp. 1038–1039.

- ^ Dolezal 2004, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Halpin & Boyes 2009.

- ^ a b Eberle & Uhl 2005, p. 288.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 1037.

- ^ Eberle & Uhl 2005, p. 282.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2008, p. 958.

- ^ MI5 staff 2011.

- ^ Isachenkov 1993.

- ^ Petrova & Watson 1995, p. 162. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPetrovaWatson1995 (help)

- ^ Vinogradov et al. 2005, p. 333.

- ^ Vinogradov et al. 2005, pp. 335–336.

Bibliography

- Bellamy, Chris (2007). Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. New York: Alfred F. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41086-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin – The Downfall 1945. New York: Viking-Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - CNN staff (11 December 2009). "Russians insist skull fragment is Hitler's". CNN. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dolezal, Robert (2004). Truth about History: How New Evidence Is Transforming the Story of the Past. Pleasantville, NY: Readers Digest. pp. 185–6. ISBN 0-7621-0523-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eberle, Henrik; Uhl, Matthias, eds. (2005). The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared for Stalin from the Interrogations of Hitler's Personal Aides. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-366-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Erickson, John (1983). The Road to Berlin: Stalin's War with Germany: Volume 2. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-77238-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fest, Joachim C. (1974). Hitler. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-141650-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fischer, Thomas (2008). Soldiers of the Leibstandarte. Winnipeg: J.J. Fedorowicz. ISBN 978-0-921991-91-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goñi, Uki (27 September 2009). "Tests on skull fragment cast doubt on Adolf Hitler suicide story". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halpin, Tony; Boyes, Roger (9 December 2009). "Battle of Hitler's skull prompts Russia to reveal all". The Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horrabin, J.F. (1946). Vol. X: May 1944 – August 1945. An Atlas-History of the Second Great War. Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson & Sons. OCLC 464378076.

- Isachenkov, Vladimir (20 February 1993). "Russians say they have bones from Hitler's skull". Gadsen Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Joachimsthaler, Anton (1999) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, The Evidence, The Truth. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-902-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kershaw, Ian (2001) [2000]. Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. Vol. 2. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-027239-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Linge, Heinz (2009). With Hitler to the End. Frontline Books–Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-804-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MI5 staff (2011). "Hitler's last days". Her Majesty's Security Service website. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - O'Donnell, James P. (2001) [1978]. The Bunker. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80958-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Petrova, Ada; Watson, Peter (1995). The Death of Hitler: The Full Story with New Evidence from Secret Russian Archives. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-03914-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosenberg, Steven (3 September 2009). "I was in Hitler's suicide bunker". BBC News. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vinogradov, V. K.; Pogonyi, J.F.; Teptzov, N.V. (2005). Hitler's Death: Russia's Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB. London: Chaucer Press. ISBN 978-1-904449-13-3.

Further reading

Books

- Bullock, Alan (1962). Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013564-0.

- Fest, Joachim (2004). Inside Hitler's Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-13577-5.

- Galante, Pierre; Silianoff, Eugene (1989). Voices From the Bunker. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-3991-3404-3.

- Gardner, Dave (2001). The Last of the Hitlers: The story of Adolf Hitler's British Nephew and the Amazing Pact to Make Sure his Genes Die Out. Worcester, UK: BMM. ISBN 978-0-9541544-0-0.

- Lehmann, Armin D. (2004). In Hitler's Bunker: A Boy Soldier's Eyewitness Account of the Führer's Last Days. Guilford, CT: Lyon's Press. ISBN 978-1-59228-578-5.

- Rzhevskaya, Elena (1965). Берлин, май 1945. Записки военного переводчика.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Ryan, Cornelius (1966). The Last Battle. New York: Simon and Schuster. OCLC 711509.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1992) [1947]. The Last Days of Hitler. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-81224-3.

- Waite, Robert G. L. (1993) [1977]. The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler. New York: DaCapo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80514-1.

Articles

- BBC staff (26 April 2000). "Russia displays 'Hitler skull fragment'". BBC.

- CNN staff (11 December 2009). "Official: KGB chief ordered Hitler's remains destroyed". CNN.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Petrova, Ada; Watson, Peter (1995). "The Death of Hitler: The Full Story with New Evidence from Secret Russian Archives". The Washington Post.