Decimal

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

- This article aims to be an accessible introduction. For the mathematical definition, see Decimal representation.

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

The decimal numeral system (also called base 10 or occasionally denary) has ten as its base. It is the numerical base most widely used by modern civilizations.[1][2]

Decimal notation often refers to a base 10 positional notation such as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system or rod calculus;[3] however, it can also be used more generally to refer to non-positional systems such as Roman or Chinese numerals which are also based on powers of ten.

A decimal number, or just decimal, refers to any number written in decimal notation, although it is more commonly used to refer to numbers that have a fractional part separated from the integer part with a decimal separator (e.g. 11.25).

A decimal may be a terminating decimal, which has a finite fractional part (e.g. 15.600); a repeating decimal, which has an infinite (non-terminating) fractional part made up of a repeating sequence of digits (e.g. 5.8144); or an infinite decimal, which has a fractional part that neither terminates nor has an infinitely repeating pattern (e.g. 3.14159265...). Decimal fractions have terminating decimal representations and other fractions have repeating decimal representations, whereas irrational numbers have infinite non-repeating decimal representations.

Decimal notation

Decimal notation is the writing of numbers in a base 10 numeral system. Examples are Brahmi numerals, Greek numerals, Hebrew numerals, Roman numerals, and Chinese numerals, as well as the Hindu-Arabic numerals used by speakers of many European languages. Roman numerals have symbols for the decimal powers (1, 10, 100, 1000) and secondary symbols for half these values (5, 50, 500). Brahmi numerals have symbols for the nine numbers 1–9, the nine decades 10–90, plus a symbol for 100 and another for 1000. Chinese numerals have symbols for 1–9, and additional symbols for powers of 10, which in modern usage reach 1072.

However, when people who use Hindu-Arabic numerals speak of decimal notation, they often mean not just decimal numeration, as above, but also decimal fractions, all conveyed as part of a positional system. Positional decimal systems include a zero and use symbols (called digits) for the ten values (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) to represent any number, no matter how large or how small. These digits are often used with a decimal separator which indicates the start of a fractional part, and with a symbol such as the plus sign + (for positive) or minus sign − (for negative) adjacent to the numeral to indicate whether it is greater or less than zero, respectively.

Positional notation uses positions for each power of ten: units, tens, hundreds, thousands, etc. The position of each digit within a number denotes the multiplier (power of ten) multiplied with that digit—each position has a value ten times that of the position to its right. There were at least two presumably independent sources of positional decimal systems in ancient civilization: the Chinese counting rod system and the Hindu-Arabic numeral system (the latter descended from Brahmi numerals).

Ten is the number which is the count of fingers and thumbs on both hands (or toes on the feet). The English word digit as well as its translation in many languages is also the anatomical term for fingers and toes. In English, decimal (decimus < Lat.) means tenth, decimate means reduce by a tenth, and denary (denarius < Lat.) means the unit of ten.

The symbols for the digits in common use around the globe today are called Arabic numerals by Europeans and Indian numerals by Arabs, the two groups' terms both referring to the culture from which they learned the system. However, the symbols used in different areas are not identical; for instance, Western Arabic numerals (from which the European numerals are derived) differ from the forms used by other Arab cultures.

Decimal fractions

A decimal fraction is a fraction the denominator of which is a power of ten.[4]

Decimal fractions are commonly expressed in decimal notation rather than fraction notation by discarding the denominator and inserting the decimal separator into the numerator at the position from the right corresponding to the power of ten of the denominator and filling the gap with leading zeros if needed, e.g. decimal fractions 8/10, 1489/100, 24/100000, and 58900/10000 are expressed in decimal notation as 0.8, 14.89, 0.00024, 5.8900 respectively. In English-speaking, some Latin American and many Asian countries, a period (.) or raised period (·) is used as the decimal separator; in many other countries, particularly in Europe, a comma (,) is used.

The integer part, or integral part of a decimal number is the part to the left of the decimal separator. (See also truncation.) The part from the decimal separator to the right is the fractional part. It is usual for a decimal number that consists only of a fractional part (mathematically, a proper fraction) to have a leading zero in its notation (its numeral). This helps disambiguation between a decimal sign and other punctuation, and especially when the negative number sign is indicated, it helps visualize the sign of the numeral as a whole.

Trailing zeros after the decimal point are not necessary, although in science, engineering and statistics they can be retained to indicate a required precision or to show a level of confidence in the accuracy of the number: Although 0.080 and 0.08 are numerically equal, in engineering 0.080 suggests a measurement with an error of up to one part in two thousand (±0.0005), while 0.08 suggests a measurement with an error of up to one in two hundred (see significant figures).

Other rational numbers

Any rational number with a denominator whose only prime factors are 2 and/or 5 may be precisely expressed as a decimal fraction and has a finite decimal expansion.[5]

- 1/2 = 0.5

- 1/20 = 0.05

- 1/5 = 0.2

- 1/50 = 0.02

- 1/4 = 0.25

- 1/40 = 0.025

- 1/25 = 0.04

- 1/8 = 0.125

- 1/125 = 0.008

- 1/10 = 0.1

If a fully reduced rational number's denominator has any prime factors other than 2 or 5, it cannot be expressed as a finite decimal fraction,[5] and has a unique eventually repeating infinite decimal expansion.

- 1/3 = 0.333333... (with 3 repeating)

- 1/9 = 0.111111... (with 1 repeating)

100 − 1 = 99 = 9 × 11:

- 1/11 = 0.090909...

1000 − 1 = 9 × 111 = 27 × 37:

- 1/27 = 0.037037037...

- 1/37 = 0.027027027...

- 1/111 = 0.009009009...

also:

- 1/81 = 0.012345679012... (with 012345679 repeating)

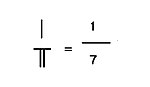

That a rational number must have a finite or recurring decimal expansion can be seen to be a consequence of the long division algorithm, in that there are at most q − 1 possible nonzero remainders on division by q, so that the recurring pattern will have a period less than q. For instance, to find 3/7 by long division:

0.4 2 8 5 7 1 4 …

7)3.0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

2 8 30 ÷ 7 = 4 with a remainder of 2

2 0

1 4 20 ÷ 7 = 2 with a remainder of 6

6 0

5 6 60 ÷ 7 = 8 with a remainder of 4

4 0

3 5 40 ÷ 7 = 5 with a remainder of 5

5 0

4 9 50 ÷ 7 = 7 with a remainder of 1

1 0

7 10 ÷ 7 = 1 with a remainder of 3

3 0

2 8 30 ÷ 7 = 4 with a remainder of 2

2 0

etc.

The converse to this observation is that every recurring decimal represents a rational number p/q. This is a consequence of the fact that the recurring part of a decimal representation is, in fact, an infinite geometric series which will sum to a rational number. For instance,

Real numbers

Every real number has a (possibly infinite) decimal representation; i.e., it can be written as

where

- sign ∈ {+,−}, which is related to the sign function,

- ℤ is the set of all integers (positive, negative, and zero), and

- ai ∈ { 0,1,...,9 } for all i ∈ ℤ are its decimal digits, equal to zero for all i greater than some number (that number being the common logarithm of |x|).

Such a sum converges as more and more negative values of i are included, even if there are infinitely many non-zero ai.

Rational numbers (e.g., p/q) with prime factors in the denominator other than 2 and 5 (when reduced to simplest terms) have a unique recurring decimal representation.

Non-uniqueness of decimal representation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

Consider those rational numbers which have only the factors 2 and 5 in the denominator, i.e., which can be written as p/2a5b. In this case there is a terminating decimal representation. For instance, 1/1 = 1, 1/2 = 0.5, 3/5 = 0.6, 3/25 = 0.12 and 1306/1250 = 1.0448. Such numbers are the only real numbers which do not have a unique decimal representation, as they can also be written as a representation that has a recurring 9, for instance 1 = 0.99999..., 1/2 = 0.499999..., etc. The number 0 = 0/1 is special in that it has no representation with recurring 9.

This leaves the irrational numbers. They also have unique infinite decimal representations, and can be characterised as the numbers whose decimal representations neither terminate nor recur.

So in general the decimal representation is unique, if one excludes representations that end in a recurring 9.

The same trichotomy holds for other base-n positional numeral systems:

- Terminating representation: rational where the denominator divides some nk

- Recurring representation: other rational

- Non-terminating, non-recurring representation: irrational

A version of this even holds for irrational-base numeration systems, such as golden mean base representation.

Decimal computation

Decimal computation was carried out in ancient times in many ways, typically in rod calculus, with decimal multiplication table used in ancient China and with sand tables in India and Middle East or with a variety of abaci.

Modern computer hardware and software systems commonly use a binary representation internally (although many early computers, such as the ENIAC or the IBM 650, used decimal representation internally).[6] For external use by computer specialists, this binary representation is sometimes presented in the related octal or hexadecimal systems.

For most purposes, however, binary values are converted to or from the equivalent decimal values for presentation to or input from humans; computer programs express literals in decimal by default. (123.1, for example, is written as such in a computer program, even though many computer languages are unable to encode that number precisely.)

Both computer hardware and software also use internal representations which are effectively decimal for storing decimal values and doing arithmetic. Often this arithmetic is done on data which are encoded using some variant of binary-coded decimal,[7][8] especially in database implementations, but there are other decimal representations in use (such as in the new IEEE 754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic).[9]

Decimal arithmetic is used in computers so that decimal fractional results can be computed exactly, which is not possible using a binary fractional representation. This is often important for financial and other calculations.[10]

History

Many ancient cultures calculated with numerals based on ten: Egyptian hieroglyphs, in evidence since around 3000 BC, used a purely decimal system,[11][12] just as the Cretan hieroglyphs (ca. 1625−1500 BC) of the Minoans whose numerals are closely based on the Egyptian model.[13][14] The decimal system was handed down to the consecutive Bronze Age cultures of Greece, including Linear A (ca. 18th century BC−1450 BC) and Linear B (ca. 1375−1200 BC) — the number system of classical Greece also used powers of ten, including, like the Roman numerals did, an intermediate base of 5.[15] Notably, the polymath Archimedes (ca. 287–212 BC) invented a decimal positional system in his Sand Reckoner which was based on 108[15] and later led the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss to lament what heights science would have already reached in his days if Archimedes had fully realized the potential of his ingenious discovery.[16] The Hittites hieroglyphs (since 15th century BC), just like the Egyptian and early numerals in Greece, was strictly decimal.[17]

The Egyptian hieratic numerals, the Greek alphabet numerals, the Hebrew alphabet numerals, the Roman numerals, the Chinese numerals and early Indian Brahmi numerals are all non-positional decimal systems, and required large numbers of symbols. For instance, Egyptian numerals used different symbols for 10, 20, to 90, 100, 200, to 900, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, to 10,000.[18] The world's earliest positional decimal system was the Chinese rod calculus[19]

Upper row vertical form

Lower row horizontal form

History of decimal fractions

According to Joseph Needham and Lam Lay Yong, decimal fractions were first developed and used by the Chinese in the 1st century BC, and then spread to the Middle East and from there to Europe.[19][20] The written Chinese decimal fractions were non-positional.[20] However, counting rod fractions were positional.[19]

Qin Jiushao in his book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections (1247) denoted 0.96644 by

- 寸

- 096644

The Jewish mathematician Immanuel Bonfils invented decimal fractions around 1350, anticipating Simon Stevin, but did not develop any notation to represent them.[22]

The Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī claimed to have discovered decimal fractions himself in the 15th century, though J. Lennart Berggren notes that positional decimal fractions were used five centuries before him by Arab mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi as early as the 10th century.[23]Al Khwarizmi introduced fraction to Islamic countries in the early 9th century, his fraction presentation was an exact copy of traditional Chinese mathematical fraction from The Mathematical Classic of Sunzi.[19] This form of fraction with numerator on top and denominator at bottom without a horizontal bar was also used by 10th century Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi and 15th century Jamshīd al-Kāshī's work "Arithmetic Key".[19][24]

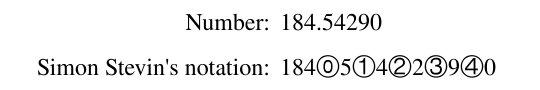

A forerunner of modern European decimal notation was introduced by Simon Stevin in the 16th century.[25]

Natural languages

The ingenious method of expressing every possible number using a set of ten symbols emerged in India. Several Indian languages show a straightforward decimal system. Many Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages have numbers between 10 and 20 expressed in a regular pattern of addition to 10.[26]

The Hungarian language also uses a straightforward decimal system. All numbers between 10 and 20 are formed regularly (e.g. 11 is expressed as "tízenegy" literally "one on ten"), as with those between 20 and 100 (23 as "huszonhárom" = "three on twenty").

A straightforward decimal rank system with a word for each order (10 十, 100 百, 1000 千, 10,000 万), and in which 11 is expressed as ten-one and 23 as two-ten-three, and 89,345 is expressed as 8 (ten thousands) 万 9 (thousand) 千 3 (hundred) 百 4 (tens) 十 5 is found in Chinese, and in Vietnamese with a few irregularities. Japanese, Korean, and Thai have imported the Chinese decimal system. Many other languages with a decimal system have special words for the numbers between 10 and 20, and decades. For example, in English 11 is "eleven" not "ten-one" or "one-teen".

Incan languages such as Quechua and Aymara have an almost straightforward decimal system, in which 11 is expressed as ten with one and 23 as two-ten with three.

Some psychologists suggest irregularities of the English names of numerals may hinder children's counting ability.[27]

Other bases

Some cultures do, or did, use other bases of numbers.

- Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures such as the Maya used a base-20 system (presumably using all twenty fingers and toes).

- The Yuki language in California and the Pamean languages[28] in Mexico have octal (base-8) systems because the speakers count using the spaces between their fingers rather than the fingers themselves.[29]

- The existence of a non-decimal base in the earliest traces of the Germanic languages, is attested by the presence of words and glosses meaning that the count is in decimal (cognates to ten-count or tenty-wise), such would be expected if normal counting is not decimal, and unusual if it were.[30][31] Where this counting system is known, it is based on the long hundred of 120 in number, and a long thousand of 1200 in number. The descriptions like 'long' only appear after the small hundred of 100 in number appeared with the Christians. Gordon's Introduction to Old Norse p 293, gives number names that belong to this system. An expression cognate to 'one hundred and eighty' is translated to 200, and the cognate to 'two hundred' is translated at 240. Goodare details the use of the long hundred in Scotland in the Middle Ages, giving examples, calculations where the carry implies i C (i.e. one hundred) as 120, etc. That the general population were not alarmed to encounter such numbers suggests common enough use. It is also possible to avoid hundred-like numbers by using intermediate units, such as stones and pounds, rather than a long count of pounds. Goodare gives examples of numbers like vii score, where one avoids the hundred by using extended scores. There is also a paper by W.H. Stevenson, on 'Long Hundred and its uses in England'. [citation needed]

- Many or all of the Chumashan languages originally used a base-4 counting system, in which the names for numbers were structured according to multiples of 4 and 16.[32]

- Many languages[33] use quinary (base-5) number systems, including Gumatj, Nunggubuyu,[34] Kuurn Kopan Noot[35] and Saraveca. Of these, Gumatj is the only true 5–25 language known, in which 25 is the higher group of 5.

- Some Nigerians use duodecimal systems.[36] So did some small communities in India and Nepal, as indicated by their languages.[37]

- The Huli language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-15 numbers.[38] Ngui means 15, ngui ki means 15 × 2 = 30, and ngui ngui means 15 × 15 = 225.

- Umbu-Ungu, also known as Kakoli, is reported to have base-24 numbers.[39] Tokapu means 24, tokapu talu means 24 × 2 = 48, and tokapu tokapu means 24 × 24 = 576.

- Ngiti is reported to have a base-32 number system with base-4 cycles.[33]

- The Ndom language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-6 numerals.[40] Mer means 6, mer an thef means 6 × 2 = 12, nif means 36, and nif thef means 36×2 = 72.

See also

References

- ^ The History of Arithmetic, Louis Charles Karpinski, 200pp, Rand McNally & Company, 1925.

- ^ Histoire universelle des chiffres, Georges Ifrah, Robert Laffont, 1994 (Also: The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer, Georges Ifrah, ISBN 0-471-39340-1, John Wiley and Sons Inc., New York, 2000. Translated from the French by David Bellos, E.F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk)

- ^ Lam Lay Yong & Ang Tian Se (2004) Fleeting Footsteps. Tracing the Conception of Arithmetic and Algebra in Ancient China, Revised Edition, World Scientific, Singapore.

- ^ "Decimal Fraction". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ a b Math Made Nice-n-Easy. Piscataway, N.J.: Research Education Association. 1999. p. 141. ISBN 0-87891-200-2.

- ^ Fingers or Fists? (The Choice of Decimal or Binary Representation), Werner Buchholz, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 2 #12, pp3–11, ACM Press, December 1959.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1983) [1974]. Decimal Computation (1 (reprint) ed.). Malabar, Florida, USA: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89874-318-4.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1974). Decimal Computation (1 ed.). Binghamton, New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-76180-X.

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers, Cowlishaw, M. F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp104-111, IEEE Comp. Soc., June 2003

- ^ Decimal Arithmetic - FAQ

- ^ Egyptian numerals

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 200-213 (Egyptian Numerals)

- ^ Graham Flegg: Numbers: their history and meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0-486-42165-0, p. 50

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp.213-218 (Cretan numerals)

- ^ a b Greek numerals

- ^ Menninger, Karl: Zahlwort und Ziffer. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Zahl, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 3rd. ed., 1979, ISBN 3-525-40725-4, pp. 150-153

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 218f. (The Hittite hieroglyphic system)

- ^ Lam Lay Yong et al The Fleeting Footsteps p 137-139

- ^ a b c d e Lam Lay Yong, "The Development of Hindu-Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic", Chinese Science, 1996 p38, Kurt Vogel notation

- ^ a b Joseph Needham (1959). "Decimal System". Science and Civilisation in China, Volume III, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Jean-Claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics, Springer 1997 ISBN 3-540-33782-2

- ^ Gandz, S.: The invention of the decimal fractions and the application of the exponential calculus by Immanuel Bonfils of Tarascon (c. 1350), Isis 25 (1936), 16–45.

- ^ Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ^ Lam Lay Yong, "A Chinese Genesis, Rewriting the history of our numeral system", Archive for History of Exact Science 38: 101–108.

- ^ B. L. van der Waerden (1985). A History of Algebra. From Khwarizmi to Emmy Noether. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ "Indian numerals". Ancient Indian mathematics. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Azar, Beth (1999). "English words may hinder math skills development". American Psychology Association Monitor. 30 (4). Archived from the original on 2007-10-21.

- ^ Avelino, Heriberto (2006). "The typology of Pame number systems and the limits of Mesoamerica as a linguistic area" (PDF). Linguistic Typology. 10 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1515/LINGTY.2006.002.

- ^ Marcia Ascher. "Ethnomathematics: A Multicultural View of Mathematical Ideas". The College Mathematics Journal. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ^ McClean, R. J. (July 1958), "Observations on the Germanic numerals", German Life and Letters, 11 (4): 293–299, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0483.1958.tb00018.x,

Some of the Germanic languages appear to show traces of an ancient blending of the decimal with the vigesimal system

. - ^ Voyles, Joseph (October 1987), "The cardinal numerals in pre-and proto-Germanic", The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 86 (4): 487–495, JSTOR 27709904.

- ^ There is a surviving list of Ventureño language number words up to 32 written down by a Spanish priest ca. 1819. "Chumashan Numerals" by Madison S. Beeler, in Native American Mathematics, edited by Michael P. Closs (1986), ISBN 0-292-75531-7.

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald (17 May 2007). "Rarities in Numeral Systems". In Wohlgemuth, Jan; Cysouw, Michael (eds.). Rethinking Universals: How rarities affect linguistic theory (PDF). Empirical Approaches to Language Typology. Vol. 45. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter (published 2010). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2007.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Harris, John (1982). Hargrave, Susanne (ed.). Facts and fallacies of aboriginal number systems (PDF). Vol. 8. pp. 153–181.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Dawson, J. "Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria (1881), p. xcviii.

- ^ Matsushita, Shuji (1998). Decimal vs. Duodecimal: An interaction between two systems of numeration. 2nd Meeting of the AFLANG, October 1998, Tokyo. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Mazaudon, Martine (2002). "Les principes de construction du nombre dans les langues tibéto-birmanes". In François, Jacques (ed.). La Pluralité (PDF). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 91–119. ISBN 90-429-1295-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Cheetham, Brian (1978). "Counting and Number in Huli". Papua New Guinea Journal of Education. 14: 16–35. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- ^ Bowers, Nancy; Lepi, Pundia (1975). "Kaugel Valley systems of reckoning" (PDF). Journal of the Polynesian Society. 84 (3): 309–324.

- ^ Owens, Kay (2001), "The Work of Glendon Lean on the Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania", Mathematics Education Research Journal, 13 (1): 47–71, doi:10.1007/BF03217098