Dixiecrat

Template:Infobox historical American political party The States' Rights Democratic Party (usually called the Dixiecrats) was a short-lived segregationist political party in the United States in 1948. It originated as a breakaway faction of the Democratic Party in 1948, determined to protect what they portrayed as the southern way of life beset by an oppressive federal government,[1] and supporters assumed control of the state Democratic parties in part or in full in several Southern states. The States' Rights Democratic Party opposed racial integration and wanted to retain Jim Crow laws and white supremacy in the face of possible federal intervention. Members were called Dixiecrats. (The term Dixiecrat is a portmanteau of Dixie, referring to the Southern United States, and Democrat.)

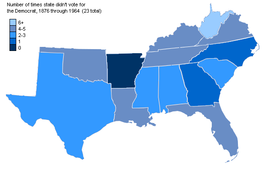

The party did not run local or state candidates, and after the 1948 election its leaders generally returned to the Democratic Party.[2] The Dixiecrats had little short-run impact on politics. However, they did have a long-term impact. The Dixiecrats began the weakening of the "Solid South" (the Democratic Party's total control of presidential elections in the South).[3]

The term "Dixiecrat" is sometimes used by Northern Democrats to refer to conservative Southern Democrats from the 1940s to the 1990s, regardless of where they stood in 1948.[4]

Background

By the 1870s, the voters of southern United States were heavily voting Democratic in national and presidential elections, and apart from minor pockets of Republican electorial strength, forming what was known as the "Solid South". The social and economic systems of the Solid South were based on Jim Crow, a combination of legal and informal segregation acts that made blacks second-class citizens with little or no political power anywhere within the southern United States.[5]

In the 1930s, the New Deal under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a realignment occurred. While many of the Democratic Party members in the southern United States had shifted toward favoring economic intervention, their own recognition of full civil rights for Black Americans was not yet incorporated within the New Deal agenda, as Southerners controlled many of the key positions of power in the U.S. Congress.

With the entry of the United States military into the Second World War, Jim Crow was indirectly challenged as two million Black Americans would serve in the U.S. military during World War II, receiving equal pay while serving within segregated units, and becoming equally entitled to receive veterans' benefits from the United States government.

Members of the Republican Party (nominating Governor of New York Thomas E. Dewey in 1944 and 1948), along with many Democrats from the northern United States, supported civil rights legislation legislation that the Deep South Democrats in Congress almost unanimously opposed.[6][7]

1948 presidential election

- See also main article, United States presidential election, 1948

When Roosevelt died, the new president Harry Truman established a highly visible President's Committee on Civil Rights and ordered an end to discrimination in the military in 1948. A group of Southern governors such as Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Fielding L. Wright of Mississippi met to consider the place of Southerners within the Democratic Party. After a tense meeting with DNC chairman and Truman confidant J. Howard McGrath, the Southern governors agreed to convene their own convention in Birmingham if Truman and civil rights supporters emerged victorious at the 1948 Democratic National Convention.[8] In July, the convention re-nominated Truman and adopted a plank proposed by Northern liberals led by Hubert Humphrey calling for civil rights; 35 southern delegates walked out. The move was on to remove Truman's name from the ballot in the southern United States. This political maneuvering required the organization of a new and distinct political party, which the Southern defectors from the Democratic Party chose to brand as the States' Rights Democratic Party.

Just days after the 1948 Democratic National Convention, the States' Rights Democrats held their own convention at Municipal Auditorium in Birmingham, Alabama on July 17.[9] While several leaders from the Deep South such as Strom Thurmond and James Eastland attended, most major Southern Democrats did not attend the conference.[10] Among those absent were Georgia Senator Richard Russell, Jr., who had finished with the second most delegates in the Democratic presidential ballot.[10]

Prior to their own States' Rights Democratic Party convention, it was not clear whether the Dixiecrats would seek to field their own candidate or simply try to prevent Southern electors from voting for Truman.[10] Many in the press predicted that if the Dixiecrats did nominate a ticket, Arkansas Governor Benjamin Travis Laney would be the presidential nominee and South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond or Mississippi Governor Fielding L. Wright would be the vice presidential nominee.[10] Laney traveled to Birmingham during the convention, but he ultimately decided that he did not want to join a third party and remained in his hotel during the convention.[10] Thurmond himself had doubts about a third-party bid, but party organizers convinced him to accept the party's nomination, with Fielding Wright as his running mate.[10] Wright's supporters had hoped that Wright would lead the ticket, but Wright deferred to Thurmond, who had greater national stature.[10] The selection of Thurmond received fairly positive reviews from the national press, as Thurmond had pursued relatively moderate policies on civil rights and did not employ the fiery rhetoric used by other segregationist leaders.[11]

The States' Rights Democrats did not formally declare themselves as being a new third party, but rather said that they were only "recommending" that state Democratic Parties vote for the Thurmond-Wright ticket.[10] The goal of the party was to win the 127 electoral votes of the Solid South in the hopes of throwing the election to the Representatives.[10] Once in the House, the Dixiecrats hoped to throw their support to whichever party would agree to their segregationist demands.[10] Even if the Republicans won an outright majority of electoral votes (as many expected in 1948), the Dixiecrats hoped that their third-party run would help the South retake its dominant position in the Democratic Party.[10] In implementing their strategy, the States' Rights Democrats faced a complicated set of state election laws, with different states having different processes for choosing presidential electors.[10] The States' Rights Democrats eventually succeeded in making the Thurmond-Wright ticket the official Democratic ticket in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.[12] In other states, they were forced to run as a third-party ticket.[13]

In numbers greater than the 6,000 that attended the first, the States' Rights Democrats held a boisterous second convention in Oklahoma City, on August 14, 1948,[14] where they adopted their party platform which stated:[15]

We stand for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race; the constitutional right to choose one's associates; to accept private employment without governmental interference, and to earn one's living in any lawful way. We oppose the elimination of segregation, the repeal of miscegenation statutes, the control of private employment by Federal bureaucrats called for by the misnamed civil rights program. We favor home-rule, local self-government and a minimum interference with individual rights.

The platform went on to say:[15]

We call upon all Democrats and upon all other loyal Americans who are opposed to totalitarianism at home and abroad to unite with us in ignominiously defeating Harry S. Truman, Thomas E. Dewey and every other candidate for public office who would establish a Police Nation in the United States of America.

In Arkansas, Democratic gubernatorial nominee Sid McMath vigorously supported Truman in speeches across the state, much to the consternation of the sitting governor, Benjamin Travis Laney, an ardent Thurmond supporter. Laney later used McMath's pro-Truman stance against him in the 1950 gubernatorial election, but McMath won re-election handily.

Efforts by States' Rights Democrats to paint other Truman loyalists as turncoats generally failed, although the seeds of discontent were planted which in years to come took their toll on Southern moderates.

On election day 1948, the Thurmond-Wright ticket carried the previously solid Democratic states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, receiving 1,169,021 popular votes and 39 electoral votes. Progressive Party nominee Henry A. Wallace drew off a nearly equal number of popular votes (1,157,172) from the Democrats' left wing, although he did not carry any states. The splits in the Democratic Party in the 1948 election had been expected to produce a victory by GOP nominee Dewey, but Truman defeated Dewey in an upset victory.

Subsequent elections

The States' Rights Democratic Party dissolved after the 1948 election, as Truman, the Democratic National Committee, and the New Deal Southern Democrats acted to ensure that the Dixiecrat movement would not return in the 1952 presidential election. Some Southern diehards, such as Leander Perez of Louisiana, attempted to keep it in existence in their districts.[16] Former Dixiecrats received some backlash at the 1952 Democratic National Convention, but all Southern delegations were seated after agreeing to a party loyalty pledge.[17] Moderate Alabama Senator John Sparkman was selected as the Democratic vice presidential nominee in 1952, helping to boost party loyalty in the South.[17] Regardless of the power struggle within the Democratic Party concerning segregation policy, the South remained a strongly Democratic voting bloc for local, state, and federal Congressional elections, but not in presidential elections.

See also

- List of political parties in the United States

- Politics of the Southern United States

- Boll weevil (politics)

- Southern Democrats

- Southern strategy

References

- ^ Lemmon, Sarah McCulloh (December 1951). "The Ideology of the 'Dixiecrat' Movement". Social Forces. 30 (2): 162–71. doi:10.2307/2571628. JSTOR 2571628.

- ^ John F. Bibby and Louis Sandy Maisel, Two parties--or more?: the American party system (1998) p 35

- ^ Kari Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968 (2001) p. 238.

- ^ see Harry Kreisler, "Institutional Change in the U.S. Congress: Conversation with Nelson W. Polsby...2002"

- ^ Perman (2009) part 4

- ^ Feldman, Glenn (August 2009). "Southern Disillusionment with the Democratic Party: Cultural Conformity and 'the Great Melding' of Racial and Economic Conservatism in Alabama during World War II". Journal of American Studies. 43 (2): 199–30. doi:10.1017/S0021875809990028.

- ^ Topping, Simon (2004). "'Never Argue with the Gallup Poll': Thomas Dewey, Civil Rights and the Election of 1948". Journal of American Studies. 38 (2): 179–98. doi:10.1017/S0021875804008400. JSTOR 27557513.

- ^ Donaldson, Gary (2000). Truman Defeats Dewey. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 118–122. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Starr, J. Barton (1970). "Birmingham and the 'Dixiecrat' Convention of 1948". Alabama Historical Quarterly. 32 (1–2): 23–50.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Frederickson, Kari (14 January 2003). The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 135–142. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Frederickson, 143

- ^ Frederickson, 145-147

- ^ Frederickson, 145-147

- ^ Kari Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968 (2001) p. 133- 147.

- ^ a b "Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party, August 14, 1948". Political Party Platforms, Parties Receiving Electoral Votes: 1840-2004. The American Presidency Project. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Glen Jeansonne, Leander Perez: Boss of the Delta (Jackson, MS:University Press of Mississippi, 1977) pp. 185-189.

- ^ a b White, William S. (25 July 1952). "Democrats Vote Today; Southerners Seated; Truman Puts His Support Behind Stevenson". New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

Further reading

- Bass, Jack, and Marilyn W. Thompson. Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond (2006)

- Black, Earl, and Merle Black. Politics and Society in the South (1989)

- Buchanan, Scott. "The Dixiecrat Rebellion: Long-Term Partisan Implications in the Deep South" (2005). Politics and Policy 33(4):754-769.

- Cohodas, Nadine. Strom Thurmond & the Politics of Southern Change (1995)

- Frederickson, Kari. The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968 (2001) 311 pp. ISBN 0-8078-4910-3. the major scholarly study online edition

- Karabell, Zachary. The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election (2001)

- Perman, Michael. Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South (2009)

External links

- Scott E. Buchanan, Dixiecrats, New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- 1948 Platform of Oklahoma's Dixiecrats

- Dixiecrats

- Defunct political parties in the United States

- History of the Southern United States

- Conservatism in the United States

- Political party factions in the United States

- Political terminology of the United States

- Democratic Party (United States)

- Far-right political parties in the United States

- White supremacy in the United States

- Political parties established in 1948

- Political repression in the United States

- 1948 establishments in the United States

- Political parties disestablished in 1948

- 1948 disestablishments in the United States