Draft:Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr (1871-1942)

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Auric (talk | contribs) 2 days ago. (Update) |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

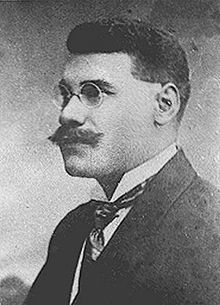

Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Mandatory Administrator of South West Africa (now Namibia) | |

| In office 1 October 1920 – 1 April 1926 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Governors‑General | |

| Preceded by | Sir Edmond Howard Lacam Gorges |

| Succeeded by | Albertus Johannes Werth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr 12 February 1871 Riversdale, Cape Colony |

| Died | 12 March 1943 (aged 72) Lakeside, Cape, Union of South Africa |

| Spouse | Ydie Louis Dankwertz Nel |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Victoria College, Stellenbosch |

Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr, CMG (1871-1942) was a South African civil servant and the first Administrator of South West Africa (now Namibia) under the League of Nations Mandate.

As a civil servant Hofmeyr had a ring-side seat on the unification of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange River colonies in 1910. The new Union of South Africa became a self-governing dominion of the British Empire.

Hofmeyr continued close to power as clerk of the new Union government’s House of Assembly from 1910 to 1920. Hofmeyr published numerous political writings including those calling for greater unity between the English and Dutch inhabitants of South Africa.

As Administrator of South West Africa from 1920 to 1926 Hofmeyr strongly encouraged white settlers from the Union and introduced numerous measures designed to ensure that the local Black and Coloured inhabitants would work for the white settlers.

Hofmeyr’s actions during the Bondelswarts Rebellion in 1922, described by Ruth First as “the Sharpeville of the 1920s”, [1] were controversial, especially the use of warplanes, aerial bombs and strafing against lightly armed Blacks.

Hofmeyr stood for election to the Parliament of South Africa for the Riversdale constituency in 1929 but lost to a nationalist opponent who taunted him about his Bondelswarts misjudgements. Thereafter the continuing rise of Afrikaner nationalism ultimately lead to the glum apartheid years.

While Hofmeyr rose above the narrow nationalism of many Afrikaners, English and Germans of his time, he, like General Smuts and other more centrist thinkers, did not match the far-sighted thinking of JW Sauer, Olive Schreiner and other contemporaries who wanted Blacks, Coloureds, Indians and Europeans (and, in the case of JW Sauer and Olive Schreiner, women) to all have the same rights and to be treated equally.

Early years[edit]

Hofmeyr was the third son and fifth child born to Afrikaner parents who farmed in Riversdale in the British Cape Colony. [2] His father, Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr (born in Cape Town in 1835, died in Riversdale in 1923) was a cousin of JH Hofmeyr, known as “Onze Jan”. His mother was Christina Jacoba van Zyl (born in 1838, died in Riversdale in 1921). Hofmeyr worked on the family farm while growing up and only had three or four years of formal education. [2] In 1895 Hofmeyr married Ydie Louise Dankwertz Nel (born in Somerset East in 1872, died in Cape Town in 1943) in Oudtshoorn. [2]. Ydie was the daughter of PAPJ Nel of Bruintes Hoogte, Somerset East. [3]

Early career[edit]

Civil service and education[edit]

In 1890, at the age of nineteen, Hofmeyr entered the Cape Civil Service [3], his first appointment being in the Lands and Deeds Office at King William’s Town. [4] Later that year Hofmeyr became Magistrate’s Clerk at Oudtshoorn, and he was subsequently attached to the Circuit Court and to various magistracies in the Cape Colony. [4] Entering the Attorney-General’s office, and after passing the relevant internal examinations, Hofmeyr acted as Civil Commissioner and Resident Magistrate at Oudtshoorn in 1894, and later in Malmesbury and then Stellenbosch. [2]

In Stellenbosch he studied after hours at Victoria College. [2] Victoria College (originally Stellenbosch College, now Stellenbosch University) had been renamed in 1887 when it acquired university status. Although later in the 20th century Stellenbosch University became a centre of strident Afrikaner nationalism, in the years that Hofmeyr was there Victoria College was a liberal institution staffed largely by Lowland Scottish “brither Presbyterians”. [5]

In 1895 the crown colony of British Bechuanaland, the southern part of the Bechuanaland Protectorate), was incorporated into the Cape Colony. The northern part remained a British Protectorate until its independence as Botswana in 1966). Hofmeyr was selected to move to Vryburg and Mafeking to assist in assimilating the system of administration there with that in vogue in the Cape Colony. [4] This early experience of incorporating British Bechuanaland into the Cape Colony would have influenced him later into thinking that integration into South Africa would be a natural progression for South West Africa.

Early political influences[edit]

Onze Jan Hofmeyr[edit]

Hofmeyr came from a family that had tried hard to foster friendliness and co-operation between English and Afrikaner (and other European nationalities). His father’s cousin was Jan Henrik Hofmeyr, known as “Onze Jan”, an influential politician and member of the Cape parliament for Stellenbosch from 1879 to 1909.

Onze Jan organisedg the farmers of the western Cape into the Afrikaner Bond [6] and by the mid 1880s, the Bond was by far the strongest party in the colony. [6] Onze Jan’s main opponent was the eloquent but erratic predicant at Paarl, the Rev Stephanus Jacobus du Toit, who in 1875 had founded a political and propagandist society call Di Genootskap van regte Afrikaners. Du Toit’s aim was for Afrikaners to “stand for our language our nation and our country”, [6] and regarded Afrikaners as a people apart who spoke Afrikaans, the taal – separate from both their Dutch ancestors and their fellow British citizens (and obviously, to him, apart from the Blacks and Coloured people). [6] Du Toit’s propositions were repugnant to Onze Jan. [6]

Onze Jan revered Dutch and did not want to reject it in favour of the simplified version of the language spoken by the people in the Cape. “I am a better man” he once said, “… I go further, I am a better Afrikander – because as well as Dutch I also know English”. [6] Onze Jan summarised it thus: “firstly, equal rights for the English and Dutch Africander; secondly, the close linking together of the Dutch and English Africander”. “Linking”, “reconciliation” and “co-operation” became favourite words of his [6], and Gysbert Reitz imbibed this philosophy, adopting the gospel of co-operation according to Onze Jan, that a South African was a white man of whatever origin who meant to live and die in the country and put its interest first. [5]

On Native policy, Onze Jan repudiated the Voortrekker dogma of racial inequality and upheld the “colour-blind” franchise of the Cape. [6] Yet he also believed (as indeed the majority of politicians in Great Britain at the time still believed) that the right to vote should be conditional on the possession of specific capacities – and only a small minority of South African Natives had as yet acquired these capacities. [6] So, although this would safeguard the voting predominance of European South Africans for a long time to come, it did leave the door open for the sharing of power in the distant future and offered in the here and now political rights to a handful of Blacks and a larger number of Coloured people, who had attained “European” standards of prosperity and later, of education. [6]

This openness of Onze Jan to allowing non-whites to vote should not be over-stated. On two occasions Onze Jan assisted in raising the voting qualifications, making it harder for Blacks and Coloureds to be allowed to vote. The Cape franchise qualification required that a person own land to the value of £25, and that communal land could be taken into account. Once the Transkei was incorporated into the Cape, the number of eligible Black voters suddenly increased. In response, in 1887 , Onze Jan supported a change to the voting qualification rules to exclude communal land.[6] In 1892 Onze Jan supported a further change to increase the required value of land held and introduce an educational qualification. [6] Onze Jan also supported the Glen Gray Act of 1894, which, among its other provisions, stimulated the Native labour supply by imposing a tax on all non-landholding Native males who did not go out to work for three months in the year. [7]

This was the world of ideas and affections within which Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr grew up. As will become evident, Onze Jan’s attitudes would strongly inform the political thought of Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr.

Hofmeyr had the deepest admiration for Onze Jan. Writing to A Brink of Kimberley on 3 April 1919, Hofmeyr states that “even making due allowance for anyone being impelled by blood relationship to a zealous veneration for the memory of a great kinsman, I venture to say that the considered verdict of the country as a whole will endorse my view that the late Onze Jan was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, stateman and patriots South Africa has produced”. [8]

Jan Smuts[edit]

Another key South African politician influenced by Onze Jan Hofmeyr and who was and would remain a strong influence on Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr was General Jan Smuts. Smuts was one year older than Hofmeyr and provided strong inspiration to Hofmeyr throughout his life as well as being his boss on numerous occasions during his career.

In 1895 Smuts in a speech in Kimberley spoke ardently of the need to fuse or consolidate the “two Teutonic peoples” of South Africa. [7] Smuts said “unless the white race closes its ranks in this country, its position will soon become untenable in the face of that overwhelming majority of prolific barbarism”. [7] Although Onze Jan Hofmeyr and Jan Smuts both wanted co-operation and equal treatment between English, Dutch (or Afrikaner) and other Europeans in South Africa, their political philosophy did not extend as far as the democratic aspirations of people like Olive Schreiner and her radical husband Samuel Cronwright, who had called upon all South Africans, irrespective of race or colour, to join forces. [7]

The political activities of both Onze Jan Hofmeyr and Jan Smuts made a deep impression on Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr, and the younger Hofmeyr decided to move closer to the corridors of power.

Cape and Transvaal parliamentary roles (1897-1907)[edit]

In 1897 Hofmeyr became Private Secretary to Dr Thomas Te Water, the Colonial Secretary of the Cape [4], and later that year Hofmeyr became the Clerk Assistant to the Cape House of Assembly [3]. In 1900 Hofmeyr was given the additional role of Registar of the Special Tribunals Court [3], and in 1904 Hofmeyr was promoted to become the Clerk of the Cape House of Assembly [3] In 1907 Hofmeyr transferred to the Transvaal Colony, becoming the first Clerk to its House of Assembly upon the formation of its Parliament under responsible government in March 1907. [4]

Early writing[edit]

Het Zuid-Afrikaanse Jaarboek (1905-1907)[edit]

From 1905 Hofmeyr was co-proprietor (with CG Murray) and editor of the annually produced Het Zuid-Afrikaanse Jaarboek en Algemeene Gids. Although the journal is presented only in Dutch, and Hofmeyr was based in Cape Town, the journal provides information on not only the Cape Colony but on all of the other British colonies and protectorates in Southern Africa too - the Transvaal Colony, the Orange River Colony, the Colony of Natal, Southern Rhodesia, and on occasion Basutoland (now Lesotho) and the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana). [9] In similar vein, the calendar lists both the British King Edward VII’s Birthday on 9 November and the Dingaan’s Day on 16 December [9] (a day commemorating the victory of 470 Voortrekkers over 20,000 Zulus). [9]

The journal presented a civil servant’s view of the world, providing a plethora of useful information. It included a calendar, replete with holy days and public holidays, school holidays in each colony, phases of the moon, sunrise and sunset times, moonrise and moonset times, tide tables and various Old Testament references. [9] Postal rates and money order details were provided. There are calculation tables showing the result of interest rates from 2.5% to 9% on different amounts over different periods in pounds, shillings and pence, tables showing how much different annual sums would provide on a monthly, weekly and daily basis, tables showing the cost of various licences, and tables showing the number of different types of sheep in each district. [9]

Longer articles described the process for the administration of estates in each colony. Census results were listed, showing the breakdown of inhabitants (split into European/ Fingo/ Maleiers/ Hottentot/ Gemengd/ Amaxosa, Zulu and other tribes), church affiliation and populations by town. The Constitution of each colony was set out (including Swaziland (now Eswatini). Members of parliament for each colony were listed, as were civil servants, attorneys and priests. The public debt and annual budget of the Cape Colony was made available. [9] Certain laws were reproduced: irrigation and water laws, hunting laws, legislation providing for half holidays for shopworkers, insolvency laws, workman’s compensation laws, agricultural laws, public health laws. [9]

Import and export figures were provided for each colony; the largest exports were gold, diamonds, wool and ostrich feathers. Two thirds of imports were from Great Britain, and almost all exports were to Great Britain. Import tariffs and railway tariffs are presented (including the rule that a short railtruck was permitted to transport no more than 16 ostriches at a time). [9]

The journal carried adverts for banks, food suppliers, hotels, furniture shops, auctioneers, schools (with St. Andrew's College, Grahamstown mentioning its exclusive annual Rhodes Scholarship), wagons, carriages (no cars), ploughs and other farm machinery, and lastly for “Dr Williams’ Pink Pills” (which was advertised as an antidote for almost every ailment imaginable). [9] The journal was not produced after 1907.

Closer Union of the South African Colonies (1908)[edit]

Hofmeyr became increasingly involved in the intellectual debate surrounding the proposed union of the British colonies and protectorates of Southern Africa.

In October 1907 Hofmeyr corresponded with Thomas B Flint, Clerk of the House of Commons of Canada, in relation to the successes of federation in Canada. [10] Flint recommended that South Africa look at the Canadian example, and use the same language relating to federations to allow it to take advantage of existing judicial determinations.[11]

In 1908 Hofmeyr published a pamphlet entitled Closer Union of the South African Colonies, in both English and Dutch. Hofmeyr regarded unification as the best scheme for the needs of the sub-continent but argued (perhaps on the strength of his Canadian correspondent) that some measure of federation must precede the bolder unification plan. Hofmeyr suggested that the Orange River Colony take over Basutoland and that the Transvaal be responsible for Swaziland. [12]

Public reaction to the pamphlet was swift. On 24 February 1908 a leader in the Transvaal Weekly complimented Hofmeyr for giving a “useful lead to other minds exercised in the same direction” and his “endeavour to form the basis of a constructive policy which must initiate all genuine progress”. [13] The leader believed that union would be the “more effective and expeditious agency in completing the cementing process between the two great white races of South Africa and by a “pooling of the best brains of the two peoples”. Hofmeyr argued that “the surrender of local self-government and prejudice must occur gradually” – but the leader criticised this as too timid and lacking boldness. The leader states, “a precarious stepping-stone (federation) is poor security, and liable to submersion when most wanted. Why not build a permanent bridge straightway of guaranteed strength and safety. This is unification”. [14]

In March 1908 Hofmeyr received a letter from M Houman, an Architect from Paterson, New Jersey, USA who had been reading the articles on Closer Union in the Transvaal Weekly. Houman advised against federation as it would not meet the aim of an independent united South Africa. [15] Houman’s advice was to not leave a “shred of autonomy or independence to any part of your country”, and to frame the body politic so that “an injury of one will be the concern of all, i.e. that England cannot injure one part without injuring the whole”.

Hofmeyr’s pamphlet was attacked in the East London Despatch, as being the views of “those of others holding high political office” or a “ballon de’essai” (a policy put forward to test reactions) of General Botha and his friends”. [16] (At the time, General Botha was Prime Minister of the Transvaal.)

In response, a leader in the Transvaal Weekly of 3 April 1908 remarked that this allegation was “decidedly unfair” and “still more unjust to Mr Hofmeyr to consider that he would act in such a capacity”. [17].

Further support for Hofmeyr came on 13 April 1908 when Lionel Phillips (President of the Transvaal Chamber of Mines) complimented Hofmeyr’s writings, saying he had presented them “in a very thoughtful and in a very dispassionate spirit” (reported in the Transvaal Weekly leader 13 April 1908). [18]

National Convention (1908-1909)[edit]

In August 1908 Hofmeyr was appointed secretary for the Transvaal delegation to the National Convention. [3] This placed him in close contact with the leading South African politicians of the day, and the debates held at the national convention strongly influenced and informed his later actions as Administrator of South West Africa.

A consensus had been emerging that the time was right for the merger of the Cape Colony, the Colony of Natal, the Orange River Colony, the Transvaal Colony and perhaps Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), Basutholand (now Lesotho), Swaziland Protectorate (now eSwatini and Bechuanaland (now Botswana. In 1908 Jan Smuts, then Colonial Secretary and Education Secretary in the Transvaal government, wrote to John X. Merriman, then Prime Minister of the Cape Colony about the need for a speedy union: during recent months, he said, a dangerous movement had been growing in the Transvaal – a movement for separatism similar to that which had existed before the Boer War. [19]

While Smuts and Merriman agreed on many things, Merriman was concerned about the Native franchise. He predicted that the Cape would not want to give it up, and the Transvaal and others would not want to adopt it. In February 1908 Merriman suggested to Smuts that their difficulty might be resolved “by leaving the question of the Native franchise to the provinces themselves”. [19]

In May 1908 delegations from the colonies met in Pretoria. Smuts moved for a resolution stating that the best interests and permanent prosperity of South Africa could only be secured by an early union of the four colonies under the Crown of Great Britain; that delegates be sent to a National South African Convention, and that it would consist of not more than twelve delegates from the Cape, eight from the Transvaal and five each from the Orange River Colony and Natal. [19]

The National Convention first met in October 1908 behind closed doors and open windows in the sultry heat of a Durban summer. [20]

Prominent members of the Transvaal delegation included General Louis Botha, then Prime Minister of the Transvaal and later the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa; General Smuts, Colonial Secretary of the Transvaal and later the second Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa (and the prime minister that appointed Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr as Administrator of South West Africa in 1920); and Sir James Percy Fitzpatrick (a mining financier and author of the classic children’s book Jock of the Bushveld), [21] who Smuts had convinced that union would be the fulfilment of the conciliation policy. [19]

Smuts also included General de la Rey in the Transvaal delegation. De la Rey knew nothing about constitutional questions but held the affectionate trust of country-dwelling Afrikaners. [19] The Transvaal delegation went with confidence and the prestige of their colony’s economic strength and political stability. Smuts was leaving nothing to chance: they also went with an expert staff of nineteen persons in all, [19] led by Hofmeyr.

The convention was held behind closed doors to foster more open debate and in the fear that a public affair would lead delegates to refuse to compromise on contentious issues. [21] The pressure on the delegates to reach agreement was intense; each delegate knew that a colony which failed to join at once could not expect to obtain ground-floor privileges later. [20]

The Convention sat at Durban from 12 October till 5 November 5 1908 and then moved to Cape Town from 23 November till February 1909. During the long debates the Transvaalers had all the advantages of wealth and preparedness over their rivals. [20]

The tide flowed strongly in the direction of unification as opposed to federation. The President, Sir Henry de Villiers, had been told much of the weaknesses of even a close federation in the course of a recent visit to Canada. [20]

Neither of the outstanding champions of federalism attended the Convention. Onze Jan Hofmeyr did not attend as he (wrongly) thought that unification had no chance of being carried. [20] William Schreiner, the leader of the Cape Bar, was unable to be there as he was defending Dinuzulu in the Natal courts for his part in the Bambatha rebellion of 1906. Schreiner believed that while such consolidation was important, human rights were vastly more important and so favoured federalism: “To embody in the South African Constitution a vertical line or barrier separating its people upon the ground of colour into a privileged class or cast and an unprivileged inferior proletariat is, as I see the problem, as imprudent as it would be to build a grand building upon unsound and sinking foundations.” [19]

Many points were settled without difficulty. Certain provisions were to be entrenched – and would require a two thirds majority to be amended. These included the legal equality of English and Dutch as official languages. [20]

Native policy and who would be entitled to vote were more contentious. Historian Eric Walker relates that a legend found currency at the time that the British authorities virtually dictated the South African bill and that the Cape delegates to the Convention did not really care much about that franchise. In Walker’s view this was not so.[20]

The British Liberal ministers brought no pressure to bear to ensure that the dominant Europeans should treat the vast non-European majority better than most of them had done hitherto, though they might have been forgiven had they done so, seeing that the very sessions of the Convention were punctuated by demands for Bantu lands from white men from all the colonies, especially from Natal. [20] The British Liberal ministers merely instructed the Earl of Selborne to make it clear to the Convention through Sir Henry de Villiers that it hoped for a general civilisation franchise. [20] The “civilisation test” would have enfranchised some at least of the non-Europeans in the ex-Republics and conversely would have disenfranchised some poor whites.[20]

This proposed breach with the traditions of the Transvaal and Orange River colonies, and, to a lesser extent, of Natal was too much for the vast majority of the delegates, and it was only with great hesitation that they agreed that the Cape should retain its non-European franchise duly entrenched and that non-Europeans should be allowed to stand for election to the Cape and Natal provincial councils.

Against these concessions, the majority succeeded in imposing a political colour bar to the extent of denying non-Europeans the right of sitting in the exclusively white Union Parliament. [20]

John X. Merriman objected to this colour bar and would not hear of the inclusion of a prayer to Almighty God in a Constitution that embodied a colour bar. When the draft bill was published, Onze Jan Hofmeyr saw to it that his Cape Town branch of the Bond should protest for the same reason. [20] The truth is that the Cape delegates cared deeply about the Cape franchise and made it clear that unless their franchise was entrenched, there would be no Union as far as the Mother Colony was concerned. [20]

Rather sadly the discussions in relation to Native policy and the proper relations between Europeans, Coloureds, Indians and Blacks did not last more than a few days of the four months of constitution-making. The principal emphasis of the discussions were on a far less difficult and far less important issue: the relationship between the two sections of the European population. [19] This approach would be replicated in Hofmeyr's approach to governing South West Africa.

Sir Henry de Villiers travelled to London to watch the passage of the bill of union at Westminster. Others went to London with a hope of influencing the British to amend the bill. William Schreiner arrived armed with a petition that a loose federation was the only means of preserving the Cape’s more liberal policies, that the incipient colour bar contained in the draft bill was “a blot on the constitution” and that the paper entrenchment of the Cape non-European franchise was a trap and no safeguard at all. [20] (All the efforts of William Schreiner could not prevent the Natal court from sentencing Dinuzulu to four years imprisonment for his almost involuntary share in the recent Bambata Rebellion.) [20]

Delegations also went to London from the African People's Organisation of Abdullah Abdurahman, and the South African Native National Conference (renamed the African National Congress in 1923), who sent John Tengo Jabavu and Walter Rubusana [20]

In the event none of these protesters were able to effect anything beyond convincing the British public that there were folk of all colours in South Africa who cared greatly for liberty and justice. [20]

It is a great pity that William Schreiner, Abdullah Abdurahman, John Tengo Jabavu and Walter Rubusana had not attended (or been invited to attend) the national convention. Had they done so Hofmeyr might have had substantial exposure to their views, and taken a more enlightened course in his administration of South West Africa.

The convention led to the adoption of the South Africa Act by the British Parliament and thereby to the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910.

Hofmeyr was appointed as Secretary to the Delimitation Committee 1909-1910, [3], the committee which was responsible for finalising the constituency boundaries ahead of the 1910 general election.

Clerk of the Assembly of the Union of South Africa (1910 to 1920)[edit]

In 1910 Hofmeyr was appointed Clerk of the House of Assembly of the newly constituted Union of South Africa, a position he held until 1920. [3] This kept him at the centre of political action in South Africa. As Clerk, Hofmeyr ranked with the Heads of Ministerial Departments. [22]

Inner History of the National Convention of South Africa (1912)[edit]

In 1912 Hofmeyr was asked, as the Clerk of the House of Assembly of the Union and as one of the secretaries to the National Convention, to read and express an opinion as to the impartiality of the record contained in Sir Edgar Walton’s book The Inner History of the National Convention of South Africa. Sir Edgar Walton had attended the National Convention as one of the Cape delegates.

As a political junior to Walton, Hofmeyr’s report was deferential. “It would be impertinent if I were to profess to be able to criticise the merits of Sir Edgar’s work”. [23]

Nonetheless Hofmeyr did suggest some amendments to the work. Hofmeyr (not without a little self-pride) felt emboldened to do so as “there is the extenuating circumstance that, as I had made a somewhat exhaustive study of the history of Closer Union movements in other countries with the view of assisting in the collection of information that might be useful to the Convention, I had taken perhaps a keener interest in the efforts of that body in their endeavours to arrive at a practical solution ... than my ordinary duties as one of the secretaries would have demanded, and for that reason perhaps the proceedings of that great gathering of South African statesmen have left on my mind a deeper and more lasting impression than would probably otherwise have been the case.” [23]

Walton’s irritation with the need for a “certification” from Hofmeyr is patent. “Mr Hofmeyr’s report is printed as an appendix to the book and it has been thought better to adopt that course rather than to attempt to reconstruct those portions to which Mr Hofmeyr alludes”. [23] Rather than prepare the seventeen page memorandum of suggested changes (infused with flattery of Walton), Hofmeyr may have done better to simply endorse Walton's account. Hofmeyr may have sensed this as he started his Memorandum with the statement that “Sir Edgar Walton’s honesty and integrity are household words with political friends and foes alike”. [23]

Hofmeyr hedges at the end of the Memorandum, stating “this manuscript was put into my hands at a time when the work of the approaching session was already coming in fast and I have, therefore, scarcely been able to give the matter the full consideration which its importance deserves.” [23] Rather than backing his output, Hofmeyr hedges further saying “I still hope it may be possible to submit the work to the scrutiny of a small committee of delegates”. [23] Walton is unlikely to have approved of a such a step.

In any event, the veracity of the book was also certified by Lord de Villiers, the President of the National Convention. [23] Walton notes in an annotation to Hofmeyr’s memorandum that he did implement the alterations suggested by Lord de Villiers (respecting his political senior).

Military inspection in Europe (1912)[edit]

The South African Defence Act 1912 created a small permanent force of 2,500 mounted police and artillery. [24] This was supplemented by some 25,000 enrolled as volunteers or conscripts drawn by lottery on a district basis, or members of Rifle Associations. These supplemental troops were very similar to the traditional commandos of the Second Boer War and were free to make their own rules and choose their officers subject to ministerial approval. [24]

General Beyers, a prominent general in the Second Boer War on the Boer side, and ex-Speaker of the pre-Union Transvaal House of Assembly, was made commandant general of the Citizen Force of the Union Defence Force. [24] In 1912 Hofmeyr accompanied General Beyers to Europe to attend military manoeuvres and inspect military institutions in each of England, Switzerland, France and Germany. [25]

This was Hofmeyr’s first trip abroad at a time when few South Africans had the opportunity to travel. [4] Newspaper reports of Hofmeyr’s travels were complimentary: “It is characteristic of Hofmeyr’s career that even now he should be able to devote little or no time to sight-seeing, but should be at the inexorable call of duty”. [4]

Award of the Order of St Michael and St George (1914)[edit]

In King George V's 1914 Birthday Honours Hofmeyr was appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in recognition of the services rendered by him as Clerk of the House of Assembly of the Union of South Africa. [26] The award was often made to holders of high office in territories of the British Empire.

Smuts’ action against white strikers (1914)[edit]

In 1914 Hofmeyr witnessed the ruthless action taken by Smuts against white strikers on the Rand.

White coal-miners in Natal went on strike at the end of 1913. In January 1914 the strike spread to the Transvaal, with white railway workers and white gold miners joining in. [24] Smuts declared martial law and called up 60,000 men from the newly constituted Union Defence Force and commandos. [24] General de la Rey led the troops, and surrounded the strikers and trained a cannon on them. The strikers capitulated. [27]

Smuts then went further. Without legal authority, he rounded up nine white labour leaders and under conditions of extreme secrecy and haste, police hustled them on board the steamship Umgeni for deportation to England [27] on the basis that they were undesirable immigrants. [24]

Later in parliament Smuts defended his actions: “we are a small white colony in a Dark Continent. Whatever divisions creep in among the whites are sure to be reflected in the conduct of the Native population, and if ever there was a country where the white people must ever be watchful and careful, and highly organised, and ready to put down with an iron hand all attempts such as were made on the present occasion, that country is South Africa”. [27]

This robust approach of Smuts is likely to have influenced Hofmeyr’s later actions as Administrator of South West Africa.

Maritz rebellion and the invasion of South West Africa (1914-1915)[edit]

Following the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, at the request of the British government, General Louis Botha, prime minister of South Africa, agreed to invade German South West Africa. South African troops were mobilised along the border between South Africa and German-controlled South West Africa. Smuts made two important decisions: to use only volunteers for the invasion of South West Africa, and secondly, to take the field himself as military commander. [21] Hofmeyr would mimic both of these decisions when faced with the Bondelswarts Rebellion in 1922.

Many of those who had fought in the Boer War regarded Smuts and Botha as traitors for being too close to the British and talk of neutrality swiftly turned into hopes of a clean break with the British empire.[1]

General Beyers, the Commandant-General of the Citizen Force of the Union Defence Force, with whom Hofmeyr had travelled to Europe for military inspections in 1912, was opposed to the South African government’s decision to undertake offensive operations against the Germans. Beyers resigned his commission on 15 September 1914. [28]

Beyers found support from a senator, General Koos de la Rey, who had been a Boer general during the Second Boer War. De la Rey (who had led the government forces against the white strikers on the Rand earlier in 1914) was a leading advocate of Boer independence and was strongly opposed to South Africa’s involvement in World War I on the side of the British and to South Africa’s proposed invasion of the German colony of South West Africa, mainly because Germany had supported the Boers during the Second Boer War. [21] Hofmeyr, as secretary to the Transvaal delegation to the National Convention, would have got to know de la Rey well as de la Rey was one of the eight Transvaal delegates. [23]

On 15 September Beyers and de la Rey set off together, travelling at night, to visit Major JCG (Jan) Kemp in Potchefstroom.[21] Kemp had also resigned his commission and had a large armoury and a force of 2,000 men who had just finished training, many of whom were thought to be sympathetic to the rebels' ideas.[21]

Although it is not known what the purpose of their visit was, the South African government believed it to be an attempt to instigate a rebellion. According to General Beyers it was to discuss plans for the simultaneous resignation of leading army officers as protest against the government's actions. [29]

A series of roadblocks had been set by police to capture the criminal gang known as the Foster gang, but the generals’ car refused to stop at one of these roadblocks and police fired on the speeding car. General de la Rey and one other were killed. [21] The subsequent judicial enquiry found that the bullet which killed de la Rey had been aimed at the back tyre of his car but had ricocheted after striking the hard road. Many believed that General de la Rey had been assassinated by the government. [21]

Lt-Col Manie Maritz, who was head of a commando of Union forces on the border of German South West Africa, allied himself with the Germans, proclaimed an independent provisional government free from British control and announced that Beyers, Kemp, Maritz and others were to be the first leaders. [21] The South African government declared martial law on 12 October 1914. [30]

Amongst Hofmeyr’s personal papers is a telegraph from “Gys” to “General Beyers, Pretoria” dated 12 October 1914, in which Hofmeyr says “Ik weet dat de opstand uw goedkeuring niet wefdraagt maar terwijl uw naam genoemd word geeft toch dadelik afkeuring publiek to kennen ten einde misbruik van uw naam hierin to voorkomen” (“I know the uprising does not have your approval, but while your name is mentioned, immediately publicly disapprove in order to prevent abuse of your name in this.”) Hofmeyr's plea went unanswered and Beyers ignored the request.

Hofmeyr’s personal papers also include a note in which he says he showed the telegraphic correspondence to WA Hofmeyr of attorneys Bisset & Hofmeyr in Adderley Street, and asked WA Hofmeyr to appeal to Steyn and Beyers. “As we were close friends, his reply shocked me beyond measure. He said “Ek sal dit .. nie doen nie. Ek keur die rebellie goed. Botha en Smuts se nekke moet gebreek word” (“I will not do that. I approve of the rebellion. Botha and Smuts' necks must be broken”). Hofmeyr continued: "I remonstrated with him to no purposes and thus ended most regrettably a valued personal friendship.” [31]

In the event, General Louis Botha and General Jan Smuts (de la Rey’s old comrades and fellow members of the Transvaal delegation to the National Convention) commanded forces loyal to the Government which greatly outnumbered the rebels and were able to swiftly put down the rebellion. [21]

Before the fighting was over Beyers was drowned as his horse was shot under him while he was trying to escape across the Vaal River. [21]

The leading Boer rebels who were captured got off relatively lightly with terms of imprisonment of six and seven years and heavy fines. Two years later they were released from prison. One notable exception was Jopie Fourie, who had failed to resign his commission before joining the rebellion. He was executed.

While the rebellion was crushed, its legacy of bitterness provided part of the political capital which put the National Party under Hertzog into office after the war. [1]

After the Maritz rebellion was suppressed, the South African army continued their operations into German South West Africa. The South Africans defeated the Germans by July 1915. It was a war without any real battles, and the South African casualties for the whole campaign totalled 113 killed and 311 wounded. [1] The German losses were very similar: 103 killed, 890 taken prisoner, 37 field guns and 22 machine guns captured. [32]

South Africa had become a self-governing British dominion in 1910, but the symbols of conquest deployed in South West Africa – the Union Jack and a banner proclaiming “Britannia still rules the waves” raised in Windhoek remained those of the British Empire. [33]

“An Undivided White South Africa: the Ideal Union” (1916)[edit]

After the bitterness and heightened emotions of the Maritz rebellion, in 1916 Hofmeyr produced a short pamphlet, in English and in Dutch, entitled “An Undivided White South Africa: The Ideal Union and how it may be achieved”. [34] In it, Hofmeyr sets out a plan to create a student “bond” or society, to foster closer union between English and Dutch (and other European) school students. [34] By way of support, letters of commendation of the plan are included, from FW Reitz (President of the South African Senate), Joel Krige (Speaker of the South African House of Assembly), and from the Superintendent of Education in each of the four provinces. [34] Each letter commends the plan, with Reitz praising the “patriotic work”, Krige being “deeply impressed with the nobility of the ideal”, commenting that it is “clear that you have given deep and anxious thought”, and others commending the “removal of the causes of racial animosity and strife”. [34]

Hofmeyr’s scheme aimed to foster closer understanding and harmony between English and Dutch children. Methods were suggested to create “fusion from the present confusion”, to dispel misunderstanding because “distrust is born of ignorance”, and to nurture adults “free from racial animosities”. [34]

The scheme’s stated objectives were to encourage respect for the Constitution, a thorough knowledge of the English and Dutch languages, mutual respect between English and Dutch, interest in South African history (and the histories of England and the Netherlands), closer contact between the child of the town and the child of the veld, pride in all great South Africans (and the purchase of portraits of them by schools), love of South African fauna, flora, scenery, climate, and interest in South African literature and arts. [34]

Under the plan students would be encouraged “to listen willingly to each other’s versions”, explore the historical origin of names, and accept that “the Dutch boy is not a rebel in embryo and that the English boy is not a jingo in the growing”. [34] Laudable aims all.

In the foreword, Hofmeyr asserted that the scheme was “entirely divorced from political questions”. [34] Nonetheless, there was of course embedded in the pamphlet a strong political programme of drawing the English and Dutch closer together, to “weld these two races into one”, and to reduce the separate identities dividing the English and Dutch. [34]

While the main focus is on English and Dutch groups, “other European children were also invited to co-operate”. [34]

At no point does it occur to Hofmeyr to extend the understanding and co-operation to all children in South Africa. Hofmeyr ignores or forgets that one of the tenets of civilisation, and certainly of the Christianity invoked in the Foreword of the pamphlet, is to treat all men and women equally. While most other white leaders at the time would also have failed to do so, there were some (such as JW Sauer and Olive Schreiner) who were more enlightened.

Hofmeyr’s aim in the pamphlet is to build up “a thoroughly united and consequently dominant white nation”. [34] He worries that “continued and permanent division of the white population must inevitably lead to their ruin. Even united, their mental and moral resources will be sorely taxed to retain that supremacy which it is essential should be preserved in a land with a vast number of inhabitants to whom civilisation has yet to be extended”. [34] Hofmeyr asserts that non-whites are not yet “civilised” but acknowledges their worth by fearing that white supremacy is at risk.

Foreshadowing the language that would be used by the League of Nations in relation to the South West Africa Mandate, Hofmeyr speaks about the duties of the Dutch and the English as the “trustees of civilisation”. [34] However tempting it is to dream about the removal of the “white” or “European” limitations of the pamphlet, and to postulate how impressive it would have been had Hofmeyr been proposing that all children in South Africa, of whatever colour, should “listen willingly to each other’s versions”, dispel the “distrust born of ignorance”, and “remove the causes of racial animosity and strife”, [34] if Hofmeyr had framed the pamphlet in those terms he would have joined a very small group of enlightened whites at the time. Even the letters of commendation speak glowingly of “improving the relationship between the two great white races” [34] without any thought of the relationships with others in South Africa. Hofmeyr was not alone in being blinkered.

The pamphlet drew positive correspondence from numerous sources in South Africa, including a Scottish teacher at the Potchefstroom High School for Boys. (14 October 1916). [35] Reading the pamphlet with the benefit of hindsight, it is heartbreaking to think that so much of Hofmeyr’s “method” was soon to be adopted by the hardline Afrikaner nationalists to build the Afrikaner nation into a defensive and divisive group that fostered enmity between races in South Africa rather than closer union. That caused substantial pain and suffering for so many for so long.

Hofmeyr continued throughout this time to be interested in constitutional affairs and was regarded by some as an expert. Indeed, In January 1920 Thomas Watt, from the office of the Minister of the Interior, writes to Hofmeyr thanking him for agreeing to write an article on the Union constitution. [36]

At the time Hofmeyr’s expressed objective was “to effect union of the white people so as to have a strong and happy nation, maintaining their virility, ruling themselves and a contented Native population in the common interests of all… governed in such a manner that the vast resources of the land might be developed … in such a way that peace and good order be continuously maintained within, and security provided against attack from without, so that the new commonwealth would add to and not draw on the strength of the Empire of which it would form part." [37] These ideals would soon be tested with Hofmeyr’s appointment as Administrator of South West Africa.

Hofmeyr’s views on language[edit]

Hofmeyr was fluent in both Dutch and English, often publishing in both languages simultaneously. In Hofmeyr’s private papers his letters to and from family are mainly in Dutch but include parts in English.

Hofmeyr was less tolerant of Afrikaans. In 1919 Hofmeyr wrote to Dr Steytler, the priest of the Dutch Reformed Church in Mouille Point, saying that he supported Dr Steytler in seeking to maintain Dutch (as opposed to Afrikaans) as the language of the church. [38] Hofmeyr spoke in the letter of “onze prachtige taal – de taal der edelste en deipste gedachten van onze voorouders” (“out beautiful language – the language of the noblest and deepest thoughts of our forefathers”).

Administrator of South West Africa (1920–1926)[edit]

After South Africa had defeated the German forces in South West Africa in 1915 it declared martial law and assumed the administration of the territory.

The German record in South West Africa was indefensible. Ruth First describes it as one of insatiable plunder first, and then, when stung beyond endurance the tribes rebelled, of ruthless, wild repression in a fury of revenge and fear. [1]

The years of martial law were, in many ways, a time of hope for the African population, many of whom genuinely expected that the new colonial masters would return land confiscated by the Germans.[39]

The new South African military administration introduced a number of reforms, which were not motivated by any commitment to humanitarianism or Cape liberalism but rather from South Africa’s desire to be permitted to retain South West Africa after the war ended. [40] The South Africans abolished flogging as a punishment for workers, removed the settlers’ ”right of paternal correction”, raised the age at which Africans were compelled to carry passes from seven to fourteen, and rescinded the ban on African ownership of livestock (but not land). [40]

Non-whites without land were given temporary reserves on vacant farmland of good quality within their former tribal areas, and were protected from ill treatment at the hands of their former masters.[41] This treatment, and the promises made by Viscount Buxton, the Governor-General of South Africa, left the Blacks and Coloureds with the impression that they would have their former tribal areas returned to them.[41]

The new administration began a post mortem on German rule. Special criminal courts tried historic cases of brutal treatment and killings by German whites of Africans. The courts took cognizance of but also railed against the former right of any German master to punish any servant. [1]

Ovamboland had remained outside of the area of German police surveillance (the “Police Zone”) and whites were not allowed access. The Ovambos were more numerous than the entire population of the Police Zone; armed and coherently organised, the Ovambos were far too serious a military obstacle to be challenged by the limited military power that had been available to the German governor. However, the South African military extended control over Ovamboland in 1917. [42]

League of Nations Mandate[edit]

In 1918 Lloyd George announced that the “desire and wishes of the peoples must be the dominant factor” in determining the fate of the German colonies.[43] “The Natives live in their various tribal organisations under chiefs and councils who are competent to consult and speak for their tribes and members and thus to represent their wishes and interests… the general principle of national self-determination is therefore as applicable in their case as those of occupied European territories”. [43]

South West Africa’s fate was only decided after World War I. However, the Great Powers heading the thirty-two countries forming the League of Nations were not ready to grant the Natives of South West Africa (or other former German possessions) self-determination. The Great Powers resolved that no territory taken from the defeated nations should be treated as spoils of war. They were to be territories under Mandate, the Mandatories to be answerable to the league for the well-being of the aboriginal people inhabiting them. [44] Britain had already paved the way for this decision.

The British “Blue Book” (1918)[edit]

To make sure that the indigenous populations would “self-determine” in favour of the British, Walter Long, the Colonial Secretary in 1918 sent secret telegrams to Viscount Buxton, the Governor-General of South Africa and others requesting them to provide “evidence of anxiety of Natives to live under British rule”.

Long received this reply from Buxton: “I cannot see how the principle of national self-determination could be applied to South West Africa …. Almost all sections of the Union would keenly resent the return of the Colony to the Germans and that would be politically disastrous, and while the Natives … would almost all certainly elect to remain under British rule they could hardly be given a more influential voice than the German inhabitants.” [43]

A plebiscite for South West Africa was never arranged.

Instead, in 1918, Britain published as a British Government Blue Book a “Report on the Natives of South West Africa and their Treatment by Germany” which had been prepared by the Administrator in Windhoek. [1]

A special Commission of Enquiry had been appointed to gather and examine accounts of conditions under German rule. The findings, the story of the German military operations against the tribes, was published in the Blue Book, [1] which carefully reported the killing of prisoners, women, girls and little boys, and of men and women who had surrendered dying at the hands of soldiers and labour overseers in camps and by the lash. [45] The Blue Book contained photographs of the crude executions, neck chains, leg and arm fetters, the flayed backs of women prisoners, and Herero refugees returning starved from the desert. [1]

The Blue Book retold the story of how in 1904, when the Herero took up arms, the Germans had the maxim and quick-firing Krupp gun which shattered the rebellion. Theodor Leutwein might at that point have negotiated peace, but before he had an opportunity to do so was superceded by General von Trotha, of Chinese Boxer rebellion notoriety. Von Trotha was not prepared to make peace until he had made a salutary example of the rebels. Herero chiefs, summoned from the field to discuss peace terms, were simply shot. Von Trotha then threw a cordon across the land to seal off all escape routes and issued his notorious extermination order which required the killing of every Herero man, woman or child [45]

Von Trotha’s proclamation was brutal: “The Herero people must now leave the country… every Herero, with or without a rifle, will be shot. I will not take over any more women and children, but I will either drive them back to their people or have them fired on".[46]

Thousands of Natives were held in the Shark Island concentration camp, where prisoners lived in fenced enclosures on the beach. Of 2,000 Nama prisoners placed on Shark Island in September 1906, 860 died from scurvy within the first four months. [45]

Theodor Leutwein later recorded the colonizer’s post-war estimate: “at the cost of several hundred millions of marks and several thousand German soldiers we have, of the three business assets of the protectorate – mining, farming and Native labour – destroyed the second entirely and two-thirds of the last”. The Herero population had been reduced from over 80,000 cattle rich tribesmen to 15,000 starving fugitives; more than half the Nama and Berg- Damara had died. [45]

The historian John Wellington is of the view that the Blue Book was nothing more than blatant propaganda for the purpose of preventing the return of the colony to Germany after the conclusion of the war. However, much of the Blue Book simply comprised translations of official reports of the Germans up to 1915.

Nonetheless, Wellington notes that the report was hypocritical, given that much of the treatment of the Natives of South West Africa by the Germans can be paralleled in British colonial history. [47]

Germany had responded to the Blue Book by producing its own “White Book”, published in Germany in 1919, (“Die Behandling der eiheimishen Befolkerung in den Kolonialen Besitzsungen Deutschlands und Englands”). This report spotlights the worst events in British Colonial History, alleging that the British were as culpable as the Germans in South West Africa. [47]

Wellington is forthright: “Let it be said at once that much of this indictment of Britain is true and it would be an ignorant and unworthy Briton who did not recognise the mistakes, the blunders, and the cruelties which stain the pages of British colonial history”. [47]

The ruthlessness of British military measures on certain occasions is incontrovertible. Field Marshall Garnet Wolseley showed no mercy at Tel-el-Kebir, nor Kitchener at Omdurman. [47]

Ruth First notes that the pacification of Algeria by the French, the rule of King Leopold’s rubber regime in the Congo, the exploitation by the Portuguese, English and Dutch of the slave-trade on the west coast of Africa, were all no less ugly. [1]

Many other examples might have been given. Caroline Elkins mentions Boris Johnson’s remark that over the last two hundred years Britain had invaded 178 countries – most of the members of the United Nations. [48] Elkins then deals in detail with the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919, the aerial bombing by the Royal Air Force during the Iraqi Revolt in 1920, the Irish War of Independence between 1919 and 1921, and the suppression of the 1919 Egyptian revolution. [49]

Elkins goes on to show that time did not bring immediate improvements. Elkins reviews British actions in the 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, the Bengal famine of 1943, the atrocities committed in the suppression of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya in ithe 1950s, in the Malayan emergency from 1948 to 1960, and in the Cyprus emergency between 1955 and 1959, amongst others. [49]

Historian John Newsinger in a chapter dealing with the use of excessive force by the British in the period 1916 to 1926 adds the Shanghai massacre of 1925. [50]

Ruth First assessed that Germany as a colonial power suffered from two substantial handicaps. It had entered the race in the last stages of colonisation, at a time when international morality had at last opened its eyes. What others had done before her, in secret or silence, she could not do without discovery and assault. Her second handicap was simply that she suffered defeat. When Britain and South Africa put on display the results of Germany’s colonial policy, it was not because they wanted to champion the African cause, but because they wanted to discredit the German one. [1]

This was the fraught context in which Hofmeyr received his appointment as Administrator of South West Africa.

Under the Mandate, Hofmeyr would have at least one of the handicaps Ruth First ascribed to the Germans: his actions would not be done in secret or in silence – they would be closely monitored by the Mandates Commission. And the League of Nations had set down principles by which Hofmeyr would be expected to govern, and to which he could be held to account.

Article 22 of the Covenant and Article 2 of the Mandate[edit]

The Mandate for South Africa to administer South West Africa, once agreed, took some time to come into effect. World War I hostilities ended on 11 November 1918. On 7 May 1919 it was agreed that South Africa would be the Mandatory power, although the Treaty of Versailles itself was only signed on 28 June 1919 [40], and the Covenant of the League of Nations only became effective on 10 January 1920. [40]

Under Article 22 of the Covenant certain “advanced nations” were mandated to administer on behalf of the League colonies and territories which as a consequence of World War I ceased to be governed by Germany and other defeated nations and which were “inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world”.[51] Each Mandatory was entrusted with the tutelage of such under-developed peoples and Article 22 stated that “the well-being and development of such peoples form a sacred trust of civilisation”.[51]

Each Mandatory was obliged to render to the Mandates Commission an annual report in respect of the territory committed to its charge. [51] The Mandates Commission sat in Geneva and met twice a year. The majority of members consisted of non-Mandatory Powers. [52]

For the first time, the administration of colonies and territories would, under the Mandate, be subject to independent international scrutiny by the Mandates Commission and not only review by the colonial power itself. Significantly, the Mandatory would not be marking its own homework.

The Mandate to administer South West Africa was given to “His Brittanic Majesty to be exercised on his behalf by the Government of the Union of South Africa”. [53]

Under Article 2 of the Mandate for German South West Africa the Mandatory was obliged to “promote to the utmost the material and moral well-being and social progress of the inhabitants of the territory”.[54] Furthermore, “the Mandatory shall see that … no forced labour is permitted except for essential public works and services, and then only for adequate remuneration”.[54]

Under the South African Treaty of Peace and South West Africa Mandate Act 1919, the administration of South West Africa was delegated by the South African parliament to the Governor General, who would exercise his functions through the Administrator of South West Africa appointed by the South African government. [55]

Appointment of Hofmeyr as Administrator of South West Africa[edit]

South West Africa remained under martial law until September 1920. [56]

Smuts chose Hofmeyr to inaugurate a civil regime with effect from 1 October 1920, and appointed Hofmeyr for a five year term.[57] The salary was set at £2,000 per year [58] (around £112,500 in 2024 money). Remuneration included a free residence in Windhoek and such local allowances as pertained to the office at such time. This represented a substantial increase from his salary of £1,584 per year at the time of his appointment. [59] The new salary was the same as the Administrator of one of the smaller Provinces in SA. [57]

Hofmeyr had benefitted from the strong recommendation given by John X Merriman to Smuts. [56] Merriman wrote to Hofmeyr on his appointment, reminding him that £1,000 had been reserved for “Bushman research” and saying that it would be “a great pity if we do not make a good show for the opportunity will soon slip by”. [60]

In early December 1920 Merriman again wrote to Hofmeyr. “How are you getting on with your Natives? Judging from faint rumbles that come through the press you will have your work cut out.” Merriman then recommends a book, The Black Problem, by Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, the son of John Tengo Jabavu, with the recommendation that the author is “worth a wilderness of Sol Plaatjes”. Merriman goes on to say that Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu is "a follower of Booker Washington of the school of work and discipline and not Du Bois and his inflated followers who thinks that salvation comes from high falutin grumbling. I wish you could get some institution like Tuskegee and someone to manage it” [60]

In the same letter, Merriman’s political acuteness is revealed: “You are going to have fine times with the League of Nations and their Mandates Commission I fear. However, my dear Excellency, I do not want to cry wolf – and at any rate you, if any one, knows the stuff of which we politicians are made.” [60]

The Cape Times greeted the appointment of Hofmeyr with approval. “It will readily be understood that … Mr Hofmeyr’s wide knowledge of constitutional forms and precedents gained as Joint Secretary in the National Convention and in the past ten builder years of the Union Parliament will be of the utmost value…. though in the House of Assembly, where he has so admirably fulfilled his important functions as Clerk of the House, he will be sorely missed, the Administrative duties to which he is to be called in the new Territory, the task of building up a civil administration and of helping to weld South West Africa into the system of the Union is one which, however, anxious and difficult it may be, must make a powerful appeal to the imagination as well as to the intellect.” [61]

Elsewhere in the Cape Times on 3 August 1920 it was reported that that “No one can doubt that the appointment, from a public point of view, is a wise one… [Hofmeyr] possesses a charm of manner and a kindness of heart which are bound to win the confidence and esteem of those with whom he will have official dealings in the South-West Protectorate… Courteous to all, he has been ever ready to help anyone over a difficulty when occasion demanded”. [62]

However, the appointment was not met with universal approval. In Hofmeyr’s papers there is an undated clipping from an unnamed newspaper (with the handwritten note “please destroy”). The article noted that Sir Howard Gorges will cease as Administrator of South West Africa and may be asked to be High Commissioner of South Africa in London, “a post that calls for far-seeing intelligence, initiative, forcefulness, tact, and administrative ability, and of these Sir Howard Gorges is a happy combination”.[63]

After lavishing praise on Sir Howard Gorges the article was decidedly lukewarm about Hofmeyr’s appointment, saying that “the selection … scarcely carries conviction with those who understand the peculiar requirements and the uncommon difficulties of the Administratorship of South-West.” [63]

Hofmeyr’s previous roles as secretary to the Transvaal delegation and clerk of the House of Assembly had required him to operate at a high-level but he had never been the principal decision maker and his appointment as Administrator may have left him feeling out of his depth.

In a letter written to Smuts on 14 December 1920, Hofmeyr seems to be under pressure and is struggling to keep up. “I am kept busy from 6am to 11pm (sometimes later)…. I am bound to say that the official atmosphere is still so pregnant with Martial Law odours that perhaps something more than disinfectants (which I have used judiciously but freely) is advisable….. I am deeply steeped in the complicated diamond question about which I have been feeling most anxious. I want to feel that all our interests are reasonably secured before Martial Law is raised. In this matter I have been greatly handicapped. A novice myself, I get very little help here. Herbst knows next to nothing; he says Gorges did not take him into his confidence. Frood is good but all a new-comer… I have had the unpleasant duty to send back to the Union one senior official, to reprimand two others and to dismiss several.” [64]

Hofmeyr’s frustration with his support team does mirror the experience of Gorges. Hancock reports that while Smuts was lucky in finding an experienced colonial administrator to put in charge of South West Africa in 1915, Gorges felt himself constrained many times to complain to Smuts about the poor quality of his subordinates in the administration and police. [21]

Hofmeyr’s early ambitions for South West Africa[edit]

Before considering Hofmeyr’s actions as Administrator, it is worth reviewing his views set out in an official Memorandum dated 4 January 1921, issued only a few months after his arrival in Windhoek as Administrator. The Memorandum sets out Hofmeyr’s early ambitions for South West Africa.

Hofmeyr noted that the Germans in South West Africa were upset with his view that “the future destiny of South-West Africa was identical with that of the Union of South Africa of which it had already become an integral or inseparable portion”. Hofmeyr suggested that as political rights and citizenship go together, German residents be regarded as British subjects by proclamation (following a precedent set in 1795 when the Dutch at the Cape were proclaimed to be British subjects) and later to be recommended by the 1921 Constitutional Commission).

However, “in the case of the Coloured and Native population, the question of the extension to them of the franchise should for the present not be considered. They will, however, also be declared to be Union subjects”. [65] No explanation for the exclusion of Coloureds and Natives from voting is given.

On education, Hofmeyr stated that he realised “the importance of one school system for European children”, and desires that wherever possible tri-lingual teachers (English/ Dutch/ German) be appointed. “Some form of education for the children of Coloured employees who hail from the Union cannot be much longer delayed”. [65] No mention is made of Black education in the memorandum.

On land, Hofmeyr’s focus would be the speed with which he can introduce white settlers. “I have bestowed much thought on the best and quickest way to get settlers on to the land and I have come to the conclusion that by a forward policy in the direction of dam construction such settlement of two thirds of the Territory could be accomplished in less than one third of the time it will take under the present system of boring for water… I am expediting the gazettal and allocation of farms as much as possible… Since 25 February 1920 when the Land Settlement Act came into force up to 31 December 1920, some 310 farms have been actually gazetted and the gazettal of 82 more is in the hands of the printer… There is urgent need for considering the quickest means of getting suitable people who desire to take up farming here on to the land”. [65]

Hofmeyr was firmly against racial mixing: “I may mention here that shortly after I took office I instructed the Land Board to insert a condition in every grant to the effect that if an allottee marries or habitually cohabits with a Coloured or Native woman he is liable to have his grant cancelled.” [65] The manner in which this complies with his Christian principles was not detailed.

Hofmeyr grappled somewhat incoherently with the “Native question”. In a statement that would become a constant refrain of his, he stated: “The Native question … in South-West Africa is synonymous with the labour question”. [65] The Native question “is one of considerable difficulty, for which the Natives are least of all to blame. They have been the unfortunate victims of untoward circumstances. Their former official masters failed to understand them for … they were sometimes very harshly treated, while at other times, the treatment was such as to bewilder a people whose mental equipment was unequal to the task of grasping such divergent methods… These unhappy people are therefore to be pitied rather than blamed where today they exhibit a spirit which is out of proper perspective…”. [65]

However, this sympathetic approach was not sustained. “ I found … that the Native drew … a sharp distinction between a German and a Union citizen and this differentiating attitude towards the white man… must be corrected at the earliest possible moment”. [65] The fact that the Native may have had cause to make such a distinction as a result of treatment detailed in the Blue Book does not occur to Hofmeyr – the attitude is something to be “corrected” in the cause of white unity.

Hofmeyr struggled to enunciate clear policies, and what he was willing to give with one hand he then tried to take back with the other. “I want to see that the aged and the women and children are well cared for and have comfortable places of abode. I want also to see that the Native who by hard work and thrift has got stock together shall have good grazing and good water for his stock. But I also want to see that there shall be no idleness which only leads to crime and punishment.” [65]

“Just as every white man has to work, so every Native must also work. Above all, they must take my advice and have nothing to do with political agitators. In times of stress and difficulty the Natives can look to me for help and protection, but on the other hand the Natives must help by working on the farms to so develop the country so that there will be food for all when hard times overtake us.” [65] For Hofmeyr, the Natives rights to fair treatment was conditional on willingness to work. “I will see that [the Natives] are well treated if they go and work and that they are paid their wages and get good food, but then I expect the Chiefs and Headmen to see that there is no idleness and that the Natives contribute their share towards making South-West Africa a good and happy country for all.” [65]

Hofmeyr was aware of the plethora of harsh laws that the Germans had introduced and expressed a desire not to repeat them. “It is because I want to avoid making ugly laws for the people that I am sending the commission to explain to them the position and to advise me as to the reasons why all the Natives who can work are not working”. [65]

Sadly, Hofmeyr ended up passing numerous “ugly laws” to ensure that Natives became available as labourers on the white owned farms, mines and elsewhere.

Hofmeyr’s indecisiveness is apparent in his views on Native risings. He bemoaned the fact that “the usual rumours of a Native rising have been floated about for weeks past and old inhabitants have urged upon me the inadvisability of moving from Windhoek without a bodyguard. I have assured these kind friends that as I was sincerely endeavouring to see that justice was done to the Natives, I feared no harm from them, did not view seriously any probability of a Native rising, and had no intention when moving about the country of increasing the discomfort by a dust-raising bodyguard which would be more likely to promote trouble than avert it.” [65] This was clear, but later in the Memorandum Hofmeyr acknowledged reports that some Natives are discontent and may rebel: “as a matter of fact I was already aware that a little drilling was going on…” [65]

On Native reserves, Hofmeyr felt that “early demarcation of reserves would facilitate and render more effective the proper registration and branding of all stock”. [65]

Hofmeyr noted that there was an immediate challenge to his authority when a draft treaty to be entered into between King George V and Kaptein Cornelis van Wijk of Rehoboth was published. Hofmeyr said he had no intention of recommending the recognition of such a treaty as the Rehoboth people were not competent to enter into it. [65] A darker side also emerges. “I would advise [the Rehoboth] to consider the expediency of putting the dogs after people who may come there again bent on drafting similar impracticable documents.” [65]

Hofmeyr also reveals a dry sense of humour. The Rehoboth claimed citizenship rights such as liquor privileges and their right to carry arms (both banned for Natives generally). Hofmeyr agreed with their contentions and agreed to consider “permits for such quantities of liquor as should be allowed to the Christian people they were”. He followed up “… I pointed out to them that South-West Africa was essentially a place where one should in all walks of life specially guard against the enticing “voice of the siren who eternally slumbers in the yellow bubbles of the whisky decanter”. [65] And finally: “If spared, I intend to spend my next birthday with [the Rehoboth] …”

The new legal framework[edit]

The transition from German rule[edit]

After the German surrender in 1915, South Africa had appointed EHL Gorges as Administrator of the Protectorate. German law remained in force except for such laws as were repealed under martial law. The German Civil Code and the German Criminal Code continued to operate, but the German administrative machinery, which included their courts, ceased to function. [66] No civil courts were established, but military magistrate’s courts exercised criminal jurisdiction. This continued up to the creation of the League of Nations Mandate over South West Africa. [66]

Martial law was withdrawn from 1 January 1921 but before this certain steps had been taken. English and Dutch replaced German as the official language. On 1 January 1920 Roman-Dutch law “as existing and applied in the Cape province” was made the “common law” of the territory and German law ceased to exist in so far as it was in conflict with this “common law”. Normal civil and criminal courts were constituted. [66]

In terms of Article 297 of the Treaty of Versailles, the Union Government was entitled to retain and liquidate all property rights and interests belonging to German nationals in the territory, but in fact no exceptional war measures were applied to landed estates belonging to German subjects.[66] The provisions of Article 297 were only applied to certain monies of diamond mining companies in the territory. [66]

Constitutional Commission[edit]

In preparation for the withdrawal of martial law, a Commission was appointed by the Union government to advise on a suitable form of civil administration to be introduced. [66] The Commission produced a muddle as it recommended that South West Africa become a fifth province of the Union albeit that the Mandate precluded this. The Commission dismissed the possibility of independence, crudely opining that “no indigenous civilisation ever existed. The Natives are still in a state of semi-barbarism, and no eventual self-government by the Native races is indicated in the Mandate.” [67]

The Commission recommended that “the form of government … should be … the form of government at present prevailing in the four Provinces of the Union, giving the population full representation in a Provincial Council and in the Union Parliament. When that stage has been reached, the Protectorate will be administered as a fifth Province of the Union… but subject always to the conditions of the Mandate. [67]

However, the commission recommended that union was only to be implemented once at least 10,000 adult male British subjects of European descent were in the Protectorate. Only those residents as would be British subjects if residing in the Union should have the right to vote. [67] “It is impossible to permit persons who do not owe allegiance to the Union to participate in shaping the political affairs of a territory which is to be administered by the Union as an integral part thereof.” [67]

The commissioners were clearly wary of the German settlers wresting political control in South West Africa away from South Africa. Probably because the Commission’s Report conflicted with the terms of the Mandate, no practical changes were made as a result of the Report.

Creation of the Advisory Counsel[edit]

The sole authority in the territory was the Administrator, who could be overridden by the Union government as the Mandatory Power. [68]

One of Hofmeyr's first acts as Administrator was to convene an Advisory Counsel of six whites to advise him. The members were to be representative of the farming, commercial, mining, wage-earning and Native interests.[69]

No Natives were to be invited onto the council. Native interests were to be looked after by Major Manning, the “Native Commissioner” (and an employee of the Administration). [70]

Under Proclamation No. 1 of 1921 the duties of the Advisory Counsel were to advise the Administrator on (a) raising of revenue, (b) appropriation of monies for public services, (c) matters of general policy and (d) any other matter requested by the Administrator.

At the first meeting Hofmeyr appealed to the Counsel, saying that “we are called upon to discourage all petty mindedness and by all means in our power to encourage broad-mindedness”. [71]

Economic measures[edit]

Hofmeyr’s objective was to establish a new colonial order, including a smooth running economy of direct benefit to South Africa. [40]