East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem refers to the part of Jerusalem captured by Jordan in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and subsequently by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. It includes Jerusalem's Old City and some of the holiest sites of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, such as the Temple Mount, Western Wall, Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The term "East Jerusalem" may refer to either the area under Jordanian rule between 1949-67 which was incorporated into the municipality of Jerusalem after 1967, covering some 70 km2 (27 sq mi) or the territory of the pre-1967 Jordanian municipality, covering 6.4 km2 (2 sq mi).

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Jerusalem was divided into two parts - the western portion, populated primarily by Jews, came under Israeli sovereignty, while the eastern portion, populated mainly by Arabs, came under Jordanian rule. Arabs living in such western Jerusalem neighbourhoods as Katamon or Malha were forced to leave; the same fate befell Jews in the eastern areas, including the Old City and the City of David. The only eastern area of the city that remained in Israeli hands throughout the 19 years of Jordanian rule was Mt. Scopus, where the Hebrew University is located, which formed an enclave during that period and therefore is not considered part of East Jerusalem. Following the 1967 Six-Day War, the eastern part of Jerusalem came under Israeli rule and was merged with the western municipality, together with several neighbouring West Bank villages. In November 1967, the United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 was passed, calling for Israel to withdraw from territories occupied in "recent conflict". In 1980, Israeli Parliament passed the Jerusalem Law declaring all of Jerusalem an "eternal and indivisible capital of the State of Israel," which has not been recognised internationally.

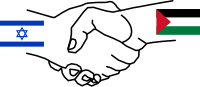

| Part of a series on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict |

| Israeli–Palestinian peace process |

|---|

|

History

Jordanian Rule

Jerusalem was designated an international city under the 1947 UN Partition Plan. It was not part of either the proposed Jewish or Arab states.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the western part of Jerusalem was captured by Israel, while East Jerusalem (including the Old City) was captured by Jordan. The 1948 Arab-Israeli War came to an end with the signing of the 1949 Armistice Agreements.[1]

Upon its capture, the Jordanians immediately expelled all the Jewish residents of the Jewish Quarter. All the main synagogues were destroyed, and the Jewish Quarter was bulldozed. The ancient Jewish cemetery on Mount of Olives was desecrated, and the tombstones there were used for construction and paving roads. Jordan also destroyed the Jewish villages of Atarot and Neve Yaakov just north of Jerusalem (their sites became Jerusalem neighborhoods after 1967).

East Jerusalem absorbed some of the refugees from West Jerusalem's Arab neighborhoods that came under Israeli rule. Thousands of Arabs were settled in the previously Jewish areas of Jerusalem.[1]

In 1950 East Jerusalem, along with the rest of the West Bank, was annexed by Jordan. However, the annexation of the West Bank was recognized only by the United Kingdom, which did not recognize the annexation of East Jerusalem. During the period of Jordanian rule, East Jerusalem lost much of its importance, as it was no longer a capital, and losing its link to the coast diminished its role as a commercial hub. It even saw a population decrease, with merchants and administrators moving to Amman. On the other hand, it maintained its religious importance, as well as its role as a regional center.

During the 1960s Jerusalem saw economic improvement and its tourism industry developed significantly, and its holy sites attracted growing numbers of pilgrims, but Israelis of all religions were not allowed into East Jerusalem.[2]. Jews were not allowed access to the Mount of Olives, Western Wall and other holy sites, in contravention of the 1949 Armistice Agreements.[1]

The Kendall Town Scheme was commissioned by the Jordanian government in 1966 to link East Jerusalem with the surrounding towns and villages, integrating them into a metropolitan area. This plan was not implemented, as East Jerusalem came under Israeli rule the following year.

Israeli Rule

During the Six-Day War of 1967 Israel captured the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and eventually incorporated 6.4 km2 (2 sq mi) of Jordanian Jerusalem and 64 km2 (25 sq mi) of the nearby West Bank into the municipality of Jerusalem, including several villages and lands from neighboring villages and towns.[3] This move excluded many of East Jerusalem's suburbs and divided several villages.

Under Israeli rule, members of all religions were largely granted access to their holy sites, with the Muslim Waqf maintaining control of the Temple Mount and Muslim holy sites there. The old Mughrabi Quarter (Morrocan) neighborhood in front of the Western Wall was demolished and replaced with a large open air plaza. The Jewish Quarter, destroyed in 1948, was rebuilt and resettled by Jews.

With the stated purpose of preventing infiltration during the Second Intifada, Israel decided to surround Jerusalem's eastern perimeter with a security barrier. The structure has separated East Jerusalem neighborhoods from the West Bank suburbs, some of which are under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority. The separation barrier has raised much criticism, and the Israeli Supreme Court has ruled that the alignment of sections of the barrier (including East Jerusalem sections) must be amended.

In the January 25, 2006 Palestinian Legislative Elections, 6,300 East Jerusalem Arabs were registered and permitted to vote locally. All other residents had to travel to West Bank polling stations. Hamas won four seats and Fatah two, even though Hamas was barred by Israel from campaigning in the city. Fewer than 6,000 residents were permitted to vote locally in the prior 1996 elections.

Demographics

The population of East Jerusalem as of 2006 was 428,304, comprising 59.5% of Jerusalem's residents. Of these, 181,457 (42%) are Jews, (comprising 39% of the Jewish population of Jerusalem), 229,004 (53%) are Muslim (comprising 99% of the Muslim population of Jerusalem and 13,638 (3%) are Christian (comprising 92% of the Christian population of Jerusalem).[4] The size of the Palestinians population living in East Jerusalem is controversial because of political implications. In 2008, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics reported the number of Palestinians living in East Jerusalem as 208,000 according to a recently completed census.[5]

East Jerusalem's main Arab neighborhoods include Shuafat (34,700), Beit Hanina (24,745), a-Sawana (22,127), Jabal Mukaber (16,030), Ras al-'Amud (14,841) and the lower part of Abu Tor (14,614). East Jerusalem's main Jewish neighborhoods include Pisgat Ze'ev (41,208), Gilo (27,258), Ramot Alon (22,460), Neve Yaakov (20,156), and East Talpiyot (12,158). The Old City has an Arab population of 32,635 and a Jewish population of 3,942.[6]

Status

Sovereignty

Since June 28 1967, East Jerusalem has been under the law, jurisdiction, and administration of the State of Israel.[7] The right of Israel to declare sovereignty over the entirety of Jerusalem is not recognized by the international community, which regarded the move as de facto annexation [8] and deemed Israeli jurisdiction invalid in a subsequent non-binding United Nations General Assembly resolution.[9] However in a reply to the resolution, Israel denied that her measures constitute annexation.[10]

In the 1980 Basic Law, or "Jerusalem Law" Israel formally declared Jerusalem "whole and united", to be "the eternal capital of Israel". The new law left the bounds of Jerusalem unspecified.[11] In response, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted the non-binding Resolution 478 (the U.S. abstained), declaring the law to be "null and void" and a violation of international law. Nevertheless, in 1988, Jordan, while rejecting Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem, withdrew all its claims to the West Bank (including East Jerusalem).

The Israeli-Palestinian Declaration of Principles, signed September 13, 1993, deferred the settlement of the permanent status of Jerusalem to the final stages of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians. The Palestinian National Authority views the future permanent status of East Jerusalem as the capital of the Palestinian state.[12] The possibility of a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem was considered by Israel for the first time in the Taba Summit in 2001,[13] though these negotiations ended without an agreement and this possibility has not been considered by Israel since.

In a 1991 letter, United States Secretary of State James Baker stated that the United States is "opposed to the Israeli annexation of east (sic) Jerusalem and the extension of Israeli law on it and the extension of Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries".[14] However, the U.S. Senate in 1990 had adopted a resolution "acknowledging Jerusalem as Israel's capital" and stating that it "strongly believes that Jerusalem must remain an undivided city."[15] Congress passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act on October 23, 1995, which declared that Jerusalem should remain undivided and that it should be recognized as Israel's capital.

Some international law experts, such as Julius Stone and Sir Elihu Lauterpacht, have argued that Israel has sovereignty over East Jerusalem under international law, since Jordan did not have legal sovereignty over the territory, and thus Israel was entitled in an act of self-defense during the Six Day War to "fill the vacuum".[16]

Residency

Following the 1967 annexation, Israel conducted a census in East Jerusalem and granted permanent Israeli residency to those Arab Jerusalemites present at the time of the census. Those not present lost the right to reside in Jerusalem. Jerusalem Palestinians were permitted to apply for Israeli citizenship, provided they met the requirements for naturalization -- such as swearing allegiance to Israel and renouncing all other citizenships -- which most of them refused to do. At the end of 2005, 93% of the Arab population of East Jerusalem had permanent residency and 5% had Israeli citizenship.[17]

As residents, East Jerusalemites rejecting Israeli citizenship have the right to vote in municipal elections and play a role in the administration of the city. Residents pay taxes, and following a 1988 Israeli Supreme Court ruling, East Jerusalem residents are guaranteed the right to social security benefits and state health care.

Until 1995, those who lived abroad for more than seven years or obtained residency or citizenship in another country were deemed liable to lose their residency status. In 1995, Israel began revoking permanent residency status from former Arab residents of Jerusalem who could not prove that their "center of life" was still in Jerusalem. This policy was rescinded four years later after it was discovered that more Arabs were moving back in order to retain their status. In March 2000, the Minister of the Interior, Natan Sharansky, stated that the "quiet deportation" policy would cease, the prior policy would be reverted, and Arab natives to Jerusalem would be able to regain residency[18] if they could prove that they have visited Israel at least once every three years. Since December 1995, permanent residency of more than 3,000 individuals "expired," leaving them with neither citizenship nor residency.[19] Despite changes in policy under Sharansky, in 2006 the number of former Arab Jerusalemites to lose their residency status was 1,363, a sixfold increase on the year before.[20] The loss of status is automatic and sometimes occurs without their knowledge.

According to the Israeli human rights organization B'Tselem, since the 1990s, policies that made construction permits harder to obtain for Arab residents have caused a housing shortage which force many of them to seek housing outside East Jerusalem.[21] Furthermore, East Jerusalem residents that are married to residents of the West Bank and Gaza have had to leave Jerusalem to join their husbands and wives due to the Citizenship Law. Furthermore, many have had to leave Jerusalem in search of work abroad since, in the aftermath of the Second Intifada East Jerusalem has increasingly been cut off from the West Bank and thereby has lost its main economic hub.[22] Israeli journalist Shahar Ilan argues that this outmigration has led many Palestinians in East Jerusalem to lose their permanent residency status.[23]

According to the American Friends Service Committee and Marshall J. Breger, such restrictions on Palestinian planning and development in East Jerusalem are part of Israel's policy of promoting a Jewish majority in the city.[24][25] On May 13, 2007, the Israeli Cabinet began discussion regarding a proposition to expand Israel's presence in East Jerusalem and boost its economy so as to attract Jewish settlers. In order to facilitate more Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem, the Cabinet is now considering an approximately 5.75 billion NIS plan to reduce taxes in the area, relocate a range of governmental offices, construct new courthouses, and build a new center for Jerusalem studies.[26] Plans to construct 25,000 Jewish homes in East Jerusalem are in the development stages. As Arab residents are hard-pressed to obtain building permits to develop existing infrastructure or housing in East Jerusalem, this proposition has received much criticism.[27][28]

Mayors of East Jerusalem

- Anwar Al-Khatib (1948-1950)

- Aref al-Aref (1950-1951)

- Hanna Atallah (1951-1952)

- Omar Wa'ari (1952-1955)

- Ruhi al-Khatib (1957-1967)

- Amin al-Majaj (1967-1999; titular)

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Israeli, Raphael. Jerusalem Divided: the armistice regime, 1947-1967, Routledge, 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Martin Gilbert, Jerusalem in the Twentieth Century (Pilmico 1996), p254.

- ^ "Israel & the Palestinians: Key Maps". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ "Table III/10 - Population of Jerusalem, By age, Population Group and Geographical Spreading, 2005" (PDF). Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem 2006/7. Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies.

- ^ Copans, Laurie (2008-02-09). "Census Finds 3.76 Million Palestinians" (HTML). WTOPnews.com. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ^ "Table III/14 - Population of Jerusalem, by Age, Quarter, Sub-Quarter and Statistical Area, 2005" (PDF). Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem 2006/7. Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies.

- ^ Law and Administration Ordinance (Amendment No. 11) Law, 1967 and Law and Administration Order (No. 1) of 28 June 1967.

- ^ Ruth Lapidoth. "Jerusalem: The Legal and Political Background". Justice No. 3, Autumn 1994. International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists.

- ^ General Assembly Resolution 2253, July 4, 1967 [1]

- ^ The letter, delivered to the U.N. Secretary General on July 10, stated: "The term 'annexation' is out of place. The measures adopted related to the integration of Jerusalem in the administrative and municipal spheres and furnish a legal basis for the protection of the Holy Places" [2].

- ^ Ian Lustick, Has Israel Annexed East Jerusalem? [3]

- ^ "On international day of solidarity with Palestinians, Secretary-General heralds Annapolis as new beginning in efforts to achieve two-state solution" (Press release). United Nations, Department of Public Information, News and Media Division. 2007-11-29. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ^ "The Moratinos' "Non-Paper" on Taba negotiations". 27 January 2001.

- ^ James Baker's Letter of Assurance to the Palestinians, 18 October 1991

- ^ "S.Con.Res.106 for the 101st Congress". Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ "Lauterpacht has offered a cogent legal analysis leading to the conclusion that sovereignty over Jerusalem has already vested in Israel. His view is that when the partition proposals were immediately rejected and aborted by Arab armed aggression, those proposals could not, both because of their inherent nature and because of the terms in which they were framed, operate as an effective legal re-disposition of the sovereign title. They might (he thinks) have been transformed by agreement of the parties concerned into a consensual root of title, but this never happened. And he points out that the idea that some kind of title remained in the United Nations is quite at odds, both with the absence of any evidence of vesting, and with complete United Nations silence on this aspect of the matter from 1950 to 1967?… In these circumstances, that writer is led to the view that there was, following the British withdrawal and the abortion of the partition proposals, a lapse or vacancy or vacuum of sovereignty. In this situation of sovereignty vacuum, he thinks, sovereignty could be forthwith acquired by any state that was in a position to assert effective and stable control without resort to unlawful means." Lacey, Ian, ed. International Law and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (pdf) - Extracts from Israel and Palestine - Assault on the Law of Nations by Julius Stone, Second Edition with additional material and commentary updated to 2003, AIJAC website. Retrieved June 28, 2007. See also Yehuda Z. Blum, The Juridical status of Jerusalem (Jerusalem, The Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations, 1974); id., "The missing Reversioner: Reflections on the Status of Judea and Samaria", 3 Israel Law Review (1968), pp. 279-301.

- ^ "Selected Statistics on Jerusalem Day 2007 (Hebrew)". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. May 14, 2007.

- ^ http://www.btselem.org/English/Jerusalem/Revocation_of_Residency.asp

- ^ http://www.btselem.org/English/Jerusalem/Revocation_of_Residency.asp

- ^ "A capital question". The Economist. May 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ^ "East Jerusalem". B'Tselem. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ Movement and access restrictions in the West Bank - Uncertainty and inefficiency in the Palestinian economy - World Bank report (9 May 2007)

- ^ Shahar Ilan (June 24, 2007). "Interior Min. increasingly revoking E. J'lem Arabs' residency permits". Haaretz.

- ^ "East Jerusalem and the Politics of Occupation" (PDF). American Friends Service Committee. Winter 2004.

- ^ Marshall J. Breger (March 1997). "Understanding Jerusalem". Middle East Quarterly. Middle East Forum.

- ^ "Cabinet discusses measures to financially strengthen Jerusalem". May 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ "New Jerusalem settlement planned". May 11, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ "Israel's Olmert says seeks to expand Jerusalem". May 13, 2007.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help)

References

- Bregman, Ahron (2002). Israel's Wars: A History Since 1947. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28716-2

- Cohen, Shaul Ephraim (1993). The Politics of Planting: Israeli-Palestinian Competition for Control of Land in the Jerusalem Periphery. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226112764

- Ghanem, As'ad (2001). The Palestinian-Arab Minority in Israel, 1948-2000: A Political Study. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791449971

- Israeli, Raphael. Jerusalem Divided: the armistice regime, 1947-1967, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0714652660, p. 118.

- Rubenberg, Cheryl A. (2003). The Palestinians: In Search of a Just Peace. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1588262251

See also

- List of East Jerusalem locations

- Jerusalem Governorate

- Rule of the West Bank and East Jerusalem by Jordan

External links

- The Legal Status of East Jerusalem Under International Law by David Storobin

- Legal status of East Jerusalem and its residents (from B'Tselem)

- History of Jerusalem (from Jewish Virtual Library)

- Jordan to reject any Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem, King tells Arafat (from Jordanian Embassy in Washington)

- The Novel Catalyst for the Jerusalem Solution A website explaining why one school for the children of the Israeli and Palestinian governments might be the missing piece needed to achieve a lasting solution

- One Jerusalem - supportive of Israel's unification of the city

- "The Hell of Israel Is Better than the Paradise of Arafat" by Daniel Pipes

- East Jerusalem and the Politics of Occupation AFSC Middle East Resource Series

- For an Equitable and Stable Jerusalem with an Agreed Political Future