Ecclesiastical Latin

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2013) |

| Ecclesiastical Latin | |

|---|---|

| Church Latin, Liturgical Latin | |

| Native to | Never spoken as a native language; other uses vary widely by period and location |

| Extinct | Still used for many purposes, mostly as liturgical language of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Holy See |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

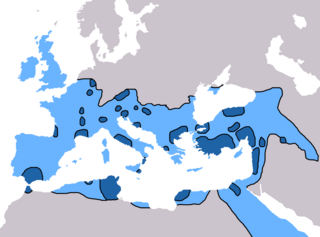

The spread of Christianity to 600 AD — the dark pockets represent initial enclaves | |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Ecclesiastical Latin, also called Liturgical Latin or Church Latin, is the form of Latin that is used in the Roman and the other Latin rites of the Catholic Church for liturgical purposes. It is distinguished from Classical Latin by some lexical variations, a simplified syntax and a pronunciation that is based on Italian.

The Ecclesiastical Latin that is used in theological works, liturgical rites and dogmatic proclamations varies in style: syntactically simple in the Vulgate Bible, hieratic in the Roman Canon of the Mass, terse and technical in Aquinas' Summa Theologica and Ciceronian in Pope John Paul II's encyclical letter Fides et Ratio.

Ecclesiastical Latin is the official language of the Holy See and the only surviving sociolect of spoken Latin.

Usage

The Church issued the dogmatic definitions of the first seven General Councils in Greek. Even in Rome, Greek remained at first the language of the liturgy and the language in which the first popes wrote. During the Late Republic and the Early Empire, educated Roman citizens were generally fluent in Greek, but state business was conducted in Latin.

The Holy See could change its official language from Latin. The chances of that happening are remote since the fact that Latin is no longer in common use makes the meaning of its words less likely to change radically from century to century. Since Latin is spoken as a native language by no modern community, the language is considered a universal, internally-consistent means of communication, without regional bias.[1]

Especially since Vatican II of 1962–1965, the Church no longer uses Latin as the exclusive language of the Roman and Ambrosian liturgies of the Latin rites of the Catholic Church. As early as 1913, the Catholic Encyclopedia commented that Latin was starting to be replaced by vernacular languages. However, the Church still produces its official liturgical texts in Latin, which provide a single clear point of reference for translations into all other languages. The same holds for the official texts of canon law and for all other doctrinal and pastoral communications and directives of the Holy See (and the Pope), such as encyclical letters, motu propriae, and declarations ex cathedra.

After the use of Latin as an everyday language died out, even among scholars, the Holy See has for some centuries usually drafted papal other documents in a modern language, but the authoritative text, the one published in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, generally appears in Latin, even if the translation is available only later. For example, the writers of the Catechism of the Catholic Church drafted it in French, the language in which it appeared in 1992. The Latin text appeared only five years later, in 1997, and the French text was corrected to match the Latin version. The Latin-language department of the Vatican Secretariat of State (formerly the Secretaria brevium ad principes et epistolarum latinarum) is charged with the preparation in Latin of papal and curial documents.

Occasionally, the official texts are published in a modern language, including such well-known texts as the motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini[2] (1903) by Pope Pius X (in Italian) and Mit brennender Sorge (1937) by Pope Pius XI (in German).

The rule now in force on the use of Latin in the Eucharistic liturgy of the Roman Rite states Mass is celebrated either in Latin or in another language, provided that the liturgical texts used have been approved according to the norm of law. Except for celebrations of the Mass that are scheduled by the ecclesiastical authorities to take place in the language of the people, priests are always and everywhere permitted to celebrate Mass in Latin.[3]

Comparison with Classical Latin

Written Church Latin does not differ radically from Classical Latin. The study of the language of Cicero and Virgil is adequate to understand Church Latin. However, those interested only in ecclesiastical texts may prefer to limit the time they devote to ancient authors, whose vocabulary covers matters of importance in that period but appear less frequently in Church documents.

In many countries, those who speak Latin for liturgical or other ecclesiastical purposes use the pronunciation that has become traditional in Rome by giving the letters the value they have in modern Italian but without distinguishing between open and close "E" and "O". "AE" and "OE" coalesce with "E"; before them and "I", "C" and "G" are pronounced /t͡ʃ/ (English "CH") and /d͡ʒ/ (English "J"), respectively. "TI" before a vowel is generally pronounced /tsi/ (unless preceded by "S", "T" or "X"). Such speakers pronounce consonantal "V" (not written as "U") as /v/ as in English, and double consonants are pronounced as such. The distinction in Classical Latin between long and short vowels is ignored, and instead of the 'macron', a horizontal line to mark the long vowel, an acute accent is used for stress. The first syllable of two-syllable words is stressed; in longer words, an acute accent is placed over the stressed vowel: adorémus 'let us adore'; Dómini 'of the Lord'.[4]

Ecclesiastics in some countries follow slightly different traditions. For instance, in Slavic and German-speaking countries, "C" commonly receives the value of /ts/ before "E" and"I", and speakers pronounce "G" in all positions hard, never as /d͡ʒ/ (English "J") . (See also Latin regional pronunciation and Latin spelling and pronunciation: Ecclesiastical pronunciation.)

Language materials

The complete text of the Bible in Latin, the revised Vulgate, appears at Nova Vulgata - Bibliorum Sacrorum Editio.[5] Another site[6] gives the entire Bible, in the Douay version, verse by verse, accompanied by the Vulgate Latin of each verse.

In 1976, the Latinitas Foundation[7] (Opus Fundatum Latinitas in Latin) was established by Pope Paul VI to promote the study and use of Latin. Its headquarters are in Vatican City. The foundation publishes an eponymous quarterly in Latin. Other initiatives of the Latinitas Foundation include the publication, in Italian, of the 15,000-word Lexicon Recentis Latinitatis (Dictionary of Recent Latin), which indicates Latin terms to use in referring to modern ideas, such as a bicycle (birota), a cigarette (fistula nicotiana), a computer (instrumentum computatorium), a cowboy (armentarius), a motel (deversorium autocineticum), shampoo (capitilavium), a strike (operistitium), a terrorist (tromocrates), a trademark (ergasterii nota), an unemployed person (invite otiosus), a waltz (chorea Vindobonensis), and even a miniskirt (tunicula minima) and hot pants (brevissimae bracae femineae). Some 600 such terms extracted from the book appear on a page[8] of the Vatican website.

Current use

Latin remains the official language of the Holy See and the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church.[9] Until the 1960s and still later in Roman colleges like the Gregorian, Roman Catholic priests studied theology using Latin textbooks, and the language of instruction in many seminaries was also Latin, which was seen as the language of the Church Fathers. The use of Latin in pedagogy and in theological research, however, has since declined. Nevertheless, canon law requires for seminary formation to provide for a thorough training in Latin.[10] Latin was still spoken in recent international gatherings of Roman Catholic leaders, such as the Second Vatican Council, and it is still used at conclaves to elect a new Pope. The Tenth Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops in 2004 was the most recent to have a Latin-language group for discussions.

Although Latin is the traditional liturgical language of the Roman (Latin) Church, the liturgical use of the vernacular has predominated since the liturgical reforms that followed the Vatican II: liturgical law for the Latin Church states that Mass may be celebrated either in Latin or another language in which the liturgical texts, translated from Latin, have been legitimately approved.[11] The permission granted for continued use of the Tridentine Mass in its 1962 form authorizes use of the vernacular language in proclaiming the Scripture readings after they are first read in Latin.[12]

See also

References

- ^ Cf. Pius XI, Apostolic Letter Officiorum omnium, 1 August 1922, and John XXIII, Apostolic Constitution Veterum sapientia, 22 February 1962

- ^ Adoremus.org

- ^ Redemptionis Sacramentum, 112 Archived February 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Roman Missal

- ^ Vatican.va

- ^ Newadvent.org

- ^ Vatican.va

- ^ Vatican.va

- ^ As stated above, official documents are frequently published in other languages. The Holy See's diplomatic languages are French and Latin (such as letters of credence from Vatican ambassadors to other countries are written in Latin [Fr. Reginald Foster, on Vatican Radio, 4 June 2005]). Laws and official regulations of Vatican City, which is an entity that is distinct from the Holy See, are issued in Italian.

- ^ Can. 249, 1983 CIC

- ^ Can. 928 Archived December 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, 1983 CIC

- ^ ["Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-01. Retrieved 2015-03-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, article 6

Sources

- The New Missal Latin by Edmund J. Baumeister, S.M., Ph.D. Published by St. Mary's Publishing Company, P.O. Box 134, St. Mary's, KS 66536-0134, USA

- A Primer of Ecclesiastical Latin by John F. Collins, (Catholic University of America Press, 1985) ISBN 0-8132-0667-7. A learner's first textbook, comparable in style, layout, and coverage to Wheelock's Latin, but featuring text selections from the liturgy and the Vulgate: unlike Wheelock, it also contains translation and composition exercises.

- Byrne, Carol (1999). "Simplicissimus". The Latin Mass Society of England and Wales. Retrieved 20 April 2011. (A course in ecclesiastical Latin.)

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (July 2012) |

Latin and the Catholic Church

- Pope John XXIII (1999) [1962]. "Veterum Sapientia: Apostolic Constitution on the Promotion of the Study of Latin". Adoremus: Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy. (in Latin here)

- "What the Church says on the Latin Language". Michael Martin.

- Una Voce - International organization promoting the Latin Tridentine Mass

- Catechism of the Catholic Church in Latin

- Fr. Nikolaus Gihr, The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass "The Language Used in the Celebration of the Holy Mass"

Bibles

- The Bible in Latin - official text of the Roman Catholic Church

- NewAdvent.org bilingual Bible

- Ordo Missae of the 1970 Roman Missal, Latin and English texts, rubrics in English only

Breviaries

Other documents

- "Documenta Latina". The Holy See. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- "Thesaurus Precum Latinarum: Treasury of Latin Prayers". Michael Martin. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

Course

- Simplicissimus, an Ecclesiastical Latin course.