Fort Baldwin

Fort Baldwin Historic Site | |

| |

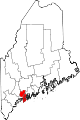

| Location | Sabino Hill, Phippsburg, Maine |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43°45′00″N 69°47′06″W / 43.75000°N 69.78500°W |

| Area | 6 acres (2.4 ha) |

| Built | 1905 |

| Architect | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| NRHP reference No. | 79000166 |

| Fort Baldwin | |

| Part of Coast Defenses of the Kennebec | |

| Phippsburg, Maine | |

| Type | Fortification |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Public - State of Maine |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1905–1912 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1912–1924, 1941–1945 |

| Materials | Reinforced concrete, earth |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison |

|

| Added to NRHP | August 3, 1979 |

Fort Baldwin is a former coastal defense fortification near the mouth of the Kennebec River in Phippsburg, Maine, United States, preserved as the Fort Baldwin State Historic Site.[1] It was named after Jeduthan Baldwin, an engineer for the Continental Army during the American Revolution. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.[2]

History

[edit]The fort was constructed between 1905 and 1912 and originally consisted of three batteries.[3][4]

Artillery batteries

[edit]- Battery Cogan with two 3-inch M1903 guns on pedestal mounts. Named in honor of a lieutenant in the 5th Continental Regiment during the American Revolution. Cogan, who had also been quartermaster of the 1st New Hampshire Regiment, died August 21, 1778.[3]

- Battery Joseph Roswell Hawley with two 6-inch M1900 guns on pedestal mounts. This battery also housed the fort's original observation station and electric equipment. Named in honor of Brigadier General Joseph R. Hawley who served with distinction during the American Civil War.[3]

- Battery Hardman with one 6-inch gun M1905 on a disappearing carriage. Named in honor of a Captain in the 2nd Maryland Regiment, Continental Army during the American Revolution. Hardman was taken prisoner at Camden, South Carolina and died while a prisoner of war on September 1, 1780.[3]

Additionally, facilities for a controlled minefield in the river were built at nearby Fort Popham.[5] The fort was in caretaker status prior to the American entry into World War I, and at some point was probably under the Coast Defenses of the Kennebec command.[3] During World War I, Fort Baldwin and Fort Popham had a garrison of 200 soldiers from the 13th and 29th Coast Artillery companies of the Coast Defenses of Portland.[2][6][7] All three 6-inch guns were withdrawn in 1917 as part of a program to put these weapons on field carriages and use them on the Western Front. Battery Hawley's guns were not sent overseas and were remounted in 1919. Battery Hardman's gun was sent to France; apparently it was eventually returned to the US but not to Fort Baldwin. A history of the Coast Artillery in World War I states that none of the regiments in France equipped with 6-inch guns completed training in time to see action before the Armistice.[8]

In 1924, Fort Baldwin was disarmed as part of a general drawdown of less-threatened coast defenses and sold to the State of Maine. Early in World War II, four circular concrete "Panama mounts" were constructed at Fort Baldwin, two of them on Battery Hawley's 6-inch gun positions. These were to provide improved firing platforms for towed 155 mm M1918 guns that were adopted by the Coast Artillery following World War I.[9] From 1941 to 1943, Battery D, 8th Coast Artillery protected Fort Baldwin and its Fire Control Tower (Built 1943) that could radio the precise position of enemy vessels to batteries in Casco Bay, notably Battery Steele with its 16-inch guns. A battery of four 155 mm guns, most likely from Fort Williams, was deployed to Fort Baldwin from early 1942 to January 17, 1944. After the war, the Army returned the property to the State of Maine in 1949.[3]

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sagadahoc County, Maine

- Seacoast defense in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "Fort Baldwin State Historic Site". Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Frank A. Beard; Robert L. Bradley (May 9, 1979). "Fort Baldwin Historic Site". National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fort Baldwin". FortWiki.

- ^ Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (2 ed.). CDSG Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- ^ "Coast Defenses of the Kennebec River: Fort Popham". American Forts Network.

- ^ Berhow, pp. 418-420

- ^ Rinaldi, Richard A. (2004). The United States Army in World War I: Orders of Battle. General Data LLC. pp. 165–166. ISBN 0-9720296-4-8.

- ^ "History of the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps during World War I". Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Berhow, p. 202

External links

[edit]- Fort Baldwin State Historic Site Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coastal Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- American Forts Network, lists forts in the US, former US territories, Canada, and Central America

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts