Francisco Solano López

Francisco Solano López | |

|---|---|

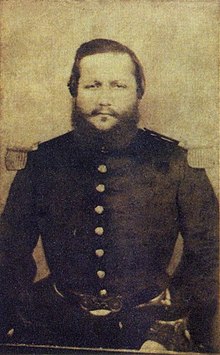

Last picture of Francisco Solano López, c. 1870 | |

| 2nd President of Paraguay | |

| In office 10 September 1862 – 1 March 1870 | |

| Vice President | Domingo Francisco Sánchez |

| Preceded by | Carlos Antonio López |

| Succeeded by | Cirilo Antonio Rivarola |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 July 1827 Asunción, Paraguay |

| Died | March 1, 1870 (aged 42) Cerro Corá, Paraguay |

| Political party | None |

| Spouse | Eliza Lynch |

| Children | Juan Francisco Corina Adelaida Enrique Venancio Federico Morgan Lloyd Carlos Honorio Leopoldo |

| Awards | |

| Signature |  |

Francisco Solano López (24 July 1827 – 1 March 1870) was President of Paraguay from 1862 until his death in 1870. He was the eldest son of Juana Pabla Carrillo and the president Carlos Antonio López. Francisco Solano López is one of the most controversial figures in Latin American history, particularly because of the Paraguayan War, known in the Plate Basin as "Guerra de la Triple Alianza".[2] From one perspective, his ambitions were the main reason for the outbreak of the war[3] while other arguments maintain he was a fierce champion of the independence of South American nations against foreign rule and interests.[4] He resisted until the very end and was killed in action during the Battle of Cerro Corá, which marked the end of the war.

Life and career

Life before the war

Solano López was born in Manorá, a barrio of Asunción in 1827. His father, Carlos Antonio Lopez, ascended to the Paraguayan Presidency in 1841 following the death of the nation's longtime dictator, José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia. The elder Lopez would commission his son as a Brigadier General in the Paraguayan Army, at the age of 18, in 1844. During the spasmodic hostilities then prevailing within Argentina, Solano Lopez was appointed commander-in-chief of Paraguayan forces stationed along the Argentine frontier.[5] He pursued his early military studies in Rio de Janeiro and Asunción (his teacher being General Hermenegildo de Albuquerque Porto Carrero[6]) specializing in fortifications and artillery.

Solano Lopez was dispatched to Europe in 1853 as minister plenipotentiary to Great Britain, France, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. Lopez went on to spend over a year and a half in Europe, most of it in Paris, where he attended military classes as a guest student in the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr, drawing the attention of Napoleon III, who decorated him with the Order of the Legion of Honour for his military skills.[7] He also served as a foreign military observer during the Crimean War.[8] He purchased large quantities of arms and military supplies, together with several steamers, on behalf of the Paraguayan military. He also modernized the Paraguayan Army with the novelties he acquired in Europe, adopting the French Code and the Prussian System of military organization (receiving some praise for this innovation many years later).[9] His diplomatic work also included organizing a project to build a new railroad and efforts to establish a French émigré colony in Paraguay. He installed the first electric telegraph in South America. Lopez also became a great admirer of the French Second Empire and developed a fascination with Napoleon Bonaparte.[10] López later equipped his army with uniforms designed to match those of the Grande Armée and it was said that he also ordered for himself an exact replica of Napoleon's crown.,[11] yet this remains unproven.[12]

It was also during his time in France that Solano Lopez met a Parisian courtesan, the Irish-born Eliza Lynch, and brought her with him back to Paraguay. There she was his concubine and de facto first lady till his death.

Solano López returned from Europe in 1855 and his father appointed him Minister of War. He was elevated to the office of Vice President in 1857.[13][14]

In November 1859, López was on board the war steamer Tacuari, which was attacked by British Royal Navy ships attempting to pressure his father into releasing a British citizen from prison. The British consul who ordered the attack was Sir William Dougal Christie, later replaced by Edward Thornton who personally supported Argentina in the War of the Triple Alliance.[15]

With his father's death in 1862, López convened Congress and was unanimously proclaimed President of Paraguay for a term of ten years.[10]

Presidency (1862–1870)

After taking office, López opted to continue most of the policies of economic protectionism and internal development adopted by his predecessors. However, he broke sharply with the traditional policy of strict isolationism in foreign affairs that was favored by previous Paraguayan leaders. López instead embarked on a more activist approach to international policy. He had, as his great ambition, to strategically position Paraguay enough to represent a credible “third force” in the ongoing political and military rivalry between Argentina and Brazil over the Rio de la Plata Basin. López wanted Paraguay to compete with the continent's major powers in the struggle for spoils and regional dominance. In pursuit of this goal López sought to organize the region’s smaller nations into a political coalition designed to off-set the power and influence of the Brazilians and the Argentines. López found an eager ally in President of Uruguay Bernardo Berro, another leader whose country was frequently menaced by the various intrigues of the continent's two great powers. Berro and López would quickly conclude an alliance and López would begin a massive expansion and reorganization of the Paraguayan military, introducing mandatory military service for all men along with other reforms. Under López, Paraguay grew to possess one of the best-trained but ill-equipped military in the region. He bought new weapons from France and England but failed to arrive because of the blockade imposed by the allies when the war broke out.

See also Fortress of Humaitá.

Role in beginning the war

In 1863, Brazil – which did not have friendly relations with Paraguay – began providing military and political support to an incipient rebellion in Uruguay led by Venancio Flores and his Colorado Party against the Blanco Party government of Berro and his successor, Atanasio Aguirre.[16] The besieged Uruguayans repeatedly asked for military assistance from their Paraguayan allies against the Brazilian-backed rebels. López manifested his support for Aguirre's government via a letter to Brazil, in which he said that any occupation of Uruguayan lands by Brazil would be considered as an attack on Paraguay.[17] When Brazil did not heed the letter and invaded Uruguay on 12 October 1864, López seized the Brazilian merchant steamer Marqués de Olinda in the harbor of Asunción[18] and imprisoned the Brazilian governor of the province of Mato Grosso, who was on board. In the following month (December 1864) Lopez formally declared war on Brazil and dispatched a force to invade Mato Grosso. The force seized and sacked the town of Corumbá and took possession of the province and its diamond mines, together with an immense quantity of arms and ammunition, including enough gunpowder to last the whole Paraguayan Army for at least a year of active war.[19] However, Paraguayan forces could not or would not seize the capital city of Cuiabá, in northern Mato Grosso.

López next intended to send troops to Uruguay to support the government of Atanasio Aguirre, yet when he requested permission from Argentina to cross Argentine soil, Argentine President Bartolomé Mitre refused to allow the Paraguayan force to cross the intervening Argentine province of Corrientes.[18] By this time the Brazilians had managed to successfully topple Aguirre and install their ally Venancio Flores as President, rendering Uruguay little more than a Brazilian puppet state.[5] The Paraguayan Congress, summoned by López, bestowed him the title of "Marshal-President" of the Paraguayan Armies (an equivalent of Grand Marshal, he was the only Paraguayan who gained that rank in his own lifetime) and gave him extraordinary war powers. On 13 April 1865, he declared war on Argentina, seizing two Argentine war vessels in the Bay of Corrientes. The next day, he occupied the town of Corrientes, instituted a provisional government of his Argentine partisans, and announced that Paraguay had annexed Corrientes Province and Argentina's Entre Ríos Province. On 1 May 1865, Brazil joined Argentina and Uruguay in signing the Treaty of the Triple Alliance, which stipulated that they should unitedly pursue war with Paraguay until the existing government of Paraguay was overthrown and "until no arms or elements of war should be left to it." This agreement was literally carried out. This treaty also stipulated that more than half of the Paraguayan territories would be conquered by the Allies after the war. The treaty, when made public, caused international outrage and voices rose in favour of Paraguay.[20]

War of the Triple Alliance

The war which ensued, lasting until 1 March 1870, was carried on with great stubbornness and with alternating fortunes, though López's disasters steadily increased. His first major setback came on June 11, 1865, when the powerless Paraguayan fleet was destroyed by the Brazilian Navy at the Battle of Riachuelo, which gave the Allies control over the various waterways surrounding Paraguay and forced Lopez to withdraw from Argentina. On 12 September 1866, López invited Mitre to a conference in Yatayty Corá. López believed that the time was right to treat for peace[21] and was ready to sign a peace treaty with the Allies.[22] No agreement was reached though since Mitre's conditions were that every article of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was still to be carried out, a condition which López refused.[18] Regardless of López's refusal, a peace treaty was not something Mitre could guarantee except on the terms of article VI of the treaty which stated that "The allies pledge themselves solemnly not to lay down their arms unless by common accord, nor until they have overthrown the present Government of Paraguay, nor to treat with the enemy separately, nor sign any Treaty of peace, truce, armistice, or Convention whatsoever for putting an end or suspending the war, unless by a perfect agreement of all".[23]

In 1868, when the allies were pressing him hard, he convinced himself that his Paraguayan supporters had actually formed a conspiracy against his life. Thereupon, several hundred prominent Paraguayan citizens were seized and executed by his order, including his brothers and brothers-in-law, cabinet ministers, judges, prefects, military officers, bishops and priests, and nine-tenths of the civil officers, together with more than two hundred foreigners, among them several members of the diplomatic legations (the San Fernando massacres). During this time, he also had his 70-year-old mother flogged and ordered her execution, because she revealed to him that he had been born out of wedlock.[24]

Battle of Cerro Corá

López was at last driven with a handful of troops to the northern frontier of Paraguay. He arrived at Cerro Corá on 14 February 1870. Two detachments were sent in pursuit of Solano López, who was accompanied by 200 men in the forests in the north, where he received news of the considerable Brazilian forces that were closing in on him. This caused some of the officials who were still with López to abandon him and approach the allied force, under the command of the Brazilian General José Antônio Correia da Câmara, which they readily joined as scouts in order to lead them to López.[25]

Upon hearing about this, López called a last war council with the remaining officers of his general staff in order to decide the course of action for the upcoming battle: whether they should escape into the hill range or stay and make a stand against the attackers. The council decided to stay and end the war once and for all by fighting to the death.[26]

The Brazilian force reached the camp on the 1 March. During the battle that ensued, López was separated from the remainder of his army and was accompanied by only his aide and a couple of officers. He had been wounded with a spear in the stomach and hit with a sword in the side of his head and so was too weak to walk by himself.[27] They led him to the Aquidabangui stream, and there they left him on the pretext of getting reinforcements. While Lopez was alone with his aide, General Câmara arrived along with six soldiers and approached him, calling on him to surrender and guaranteeing his life. López refused and shouting ¡Muero con mi patria!, (I die with my nation),[28] tried to attack Câmara with his sword. Câmara ordered him to be disarmed, but López died during the struggle with the soldiers who were trying to disarm him.[29] This incident marked the end of the war of the Triple Alliance.

Legacy

There is a debate within Paraguay as to whether he was a fearless leader who led his troops to the end or whether he foolishly led Paraguay into a war that it could never possibly win and nearly eliminated the country from the map. The debate was not helped by the revisionist stance taken by the Stroessner regime on national history. Conversely, he is considered by some Latin Americans as a champion for the rights of smaller nations against the imperialism of more powerful neighbors. For example, Eduardo Galeano argues that he and his father continued the work of José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia in defending Paraguay as "the only country that foreign capital had not deformed".[30]

There is an ongoing debate in Paraguay among historians on López's final words. The two versions are Muero por mi patria ("I die for my nation") or 'Muero con mi patria ("I die with my nation").[31] (The latter it may have been based on the testament of Luís de Camões.) In any case, Juan Silvano Godoi wrote on the event:

Marshal López died profoundly convinced that, along with him, the independence of Paraguay would disappear. He acquired this conviction upon learning that the allies had organized in Asuncion a "temporary government" made up of the Paraguayans who had taken arms against their government and fought for the Triple Alliance army.[31]

On 1 March, a national holiday in Paraguay, "Dia de los Heroes" (Heroes' Day) is held in honor of López's memory. It is the most important holiday in the country after Independence Day. López is still considered to be the greatest Paraguayan national hero, and his remains are located at the "Panteon de los Heroes" (National Pantheon of the Heroes) in Asunción. It is customary in Asunción that when something historically worth celebrating happens (such as the victory of the former President Lugo in the 2008 elections), people flock with their flags to the street in front of the Pantheon and celebrate the event.

In 2007, Argentine President Cristina Kirchner named an Argentinean military unit after Marshal Francisco Solano López. It was the 2nd Armored Artillery Group.[32] During the ceremony, the national anthems of both nations were sung and high-ranking officers of both armies were present. The Chief of the Argentine Army gave a speech at the event in which he stated: "Talking about the Paraguayan Army and the Argentine Army is talking of one and the same thing. Today, in the Argentine army, honored by the visit of Paraguay's Army Commandant, we are working intensely in fulfilling the dream of the fathers of our nation. Of those men who wanted to build a great nation, General San Martín and, precisely, Marshal López.".[32] Afterwards, Lieutenant General Bendini said:

Marshall López inspired in his men a spirit and love for their land which made them prefer to die rather than surrendering. He is an example of what a leader is, a driver, a man who knows how to reach to his people. I am sure that the men of this artillery group will take the example of this brave Paraguayan soldier and will be deemed worthy of the name their unit carries.[32]

At the end of the ceremony, the Paraguayan Army Commandant presented the unit with a portrait of López. Commenting, a leader in the Buenos Aires La Nación, a newspaper founded by Bartolomé Mitre, said under the headline "Absurd tribute to a dictator":

Naming a military unit after the dictator who trampled on the [Argentine] flag is as absurd as if France or Poland called one of their regiments "Adolf Hitler".[33]

The Paraguayan President's Office is called "Palacio de López" (Lopez's Palace), as it had been built by López before the war as his home. However, since it was not finished until after the war was over, he never resided in it.

The life of López is the basis for the play Visions by Louis Nowra.

References

- ^ "El Prendedor de Madame Lynch", written by Javier Yubi. ABC Color, (Paraguay) – 12 November 2014 (in Spanish) http://www.abc.com.py/edicion-impresa/politica/el-prendedor-de-madame-lynch-1305271.htmlarticle – It can be read, in the 5th paragraph: “Napoleón III le otorgó la Orden Imperial de la Legión de Honor en el grado de Comendador. En marzo (1854), el rey de Cerdeña le condecoró como Comendador de San Mauricio y San Lázaro. En Roma fue recibido por el secretario de Estado del papa Pío IX, el 12 de abril de 1854, donde recibió la Suprema Orden Ecuestre de la Milicia de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo (Suprema Orden de Cristo)”.

- ^ Thomas L. Whigham. "The Paraguayan War: I: Causes and Early Conduct. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2002"

- ^ Charles A. Washburn: "The history of Paraguay, with notes of personal observations, and reminiscences of diplomacy under difficulties"; Boston: Lee & Shepard; New York, Lee, Shepard, and Dillingham, 1871

- ^ Martin T. McMahon: "Paraguay and Her Enemies: and Other Texts Regarding the Paraguayan War"; New York, 1870 – ISBN 978-1482685879

- ^ a b Hanratty, Dannin M. and Meditz, Sandra W., editors. Paraguay: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1988.

- ^ Juan E. O'Leary: "El Mariscal Francisco Solano López"; Editorial Paraguaya, 1925

- ^ Manlio Cancogni and Ivan Boris: "The Napoleon of El Plata", Rizzoli Editions, Milan, 1970

- ^ Louis Schneider: "Der Krieg der Triple-Allianz"; B. Behr (E. Bock), 1872

- ^ Peter A. Schmitt: "Paraguay und Europa. Die diplomatischen Beziehungen unter Carlos Antonio Lopez und Francisco Solano Lopez 1841–1870"; Berlin: Colloquium Verl. 1963. 366 S., 12 S. Abb. 8°

- ^ a b Hanratty

- ^ Shaw, Karl (2005) [2004]. Power Mad! [Šílenství mocných] (in Czech). Praha: Metafora. pp. 29–30. ISBN 80-7359-002-6.

- ^ Hendrik Kraay, Thomas Whigham: "I Die with My Country: Perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870"; Nebraska Press, 2004

- ^ "Historical list". ABC Digital.

- ^ "Gallery". Vicepresidency of Paraguay. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ TRATADO DE LAS PUNTAS DEL ROSARIO (Guerra del Paraguay) Template:Es icon

- ^ Vasconsellos, Victor N. Resumen de Historia del Paraguay. Delimitaciones Territoriales’’, Industria Grafica Comuneros S.A. Asunción, Paraguay, 1970. Page 107.

- ^ Vasconsellos. Page 107.

- ^ a b c Vasconsellos. Page 108.

- ^ Washburn,Charles A. "History of Paraguay" Lee and Shepard, Publishers. 1871. Vol II Page 9.

- ^ George Thompson: "The War in Paraguay: With a Historical Sketch of the Country and Its People and Notes Upon the Military Engineering of the War"; Longmans, Green, and Company, 1869

- ^ Cardozo, Efrain"Breve Historia del Paraguay"El Lector. 1996. Page 87

- ^ Vasconsellos. Page 108

- ^ English translation of text from the article Treaty of the Triple Alliance, where the source is stated.

- ^ Shaw, Karl (2005) [2004]. Power Mad! [Šílenství mocných] (in Czech). Praha: Metafora. pp. 11–12. ISBN 80-7359-002-6.

- ^ Bareiro Saguier, Ruben; Villagra Marsal, Carlos. Testimonios de la Guerra Grande. Muerte del Mariscal López. Tomo I, Editorial Servilibro. Asuncion, Paraguay, 2007. Page 66.

- ^ Bareiro. Page 66.

- ^ Bareiro. Page 68, 80.

- ^ Bareiro. Page 70, 82, 98.

- ^ Bareiro. Page 90.

- ^ Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1973, 1997, pp 188–189.

- ^ a b Bareiro. Page 85.

- ^ a b c "Bautizan unidad militar Argentina en honor al prócer paraguayo Mariscal Francisco Solano López". Archived from the original on 22 January 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ La Nación, 6 December 2007.

Sources

- Bray, Arturo (1984). Solano López: soldado de la gloria y del infortunio (in Spanish) (3 ed.). Asunción: Carlos Schauman Editor.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graham, Robert Bontine Cunninghame (1933). Portrait of a dictator. London: William Heinemann.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leuchars, Chris (2002). To the bitter end: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32365-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Munro, Dana Gardner (1960). The Latin American Republics: A History (3 ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Raine, Philip (1956). Paraguay. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reber, Vera Blinn. "Francisco Solano López" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3, p. 454. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Saeger, James Schofield (2007). Francisco Solano López and the Ruination of Paraguay: Honor and Egocentrism. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-3754-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whigham, Thomas L. (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and early conduct. Vol. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4786-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - García Mellid, Atilio (1959). Proceso a los Falsificadores de la Historia del Paraguay (in Spanish) (1 ed.). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Theoria.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McMahon, Martin T. (1870). Paraguay and Her Enemies: and Other Texts Regarding the Paraguayan War (1 ed.). New York: Harper's New Monthly Magazine.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)