Friendly number

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2011) |

In number theory, friendly numbers are two or more natural numbers with a common abundancy, the ratio between the sum of divisors of a number and the number itself. Two numbers with the same abundancy form a friendly pair; n numbers with the same abundancy form a friendly n-tuple.

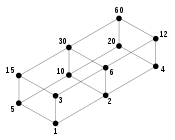

Being mutually friendly is an equivalence relation, and thus induces a partition of the positive naturals into clubs (equivalence classes) of mutually friendly numbers.

A number that is not part of any friendly pair is called solitary.

The abundancy of n is the rational number σ(n) / n, in which σ denotes the sum of divisors function. A number n is a friendly number if there exists m ≠ n such that σ(m) / m = σ(n) / n. Note that abundancy is not the same as abundance which is defined as σ(n) − 2n.

Abundancy may also be expressed as where denotes a divisor function with equal to the sum of the k-th powers of the divisors of n.

The numbers 1 through 5 are all solitary. The smallest friendly number is 6, forming for example the friendly pair 6 and 28 with abundancy σ(6) / 6 = (1+2+3+6) / 6 = 2, the same as σ(28) / 28 = (1+2+4+7+14+28) / 28 = 2. The shared value 2 is an integer in this case but not in many other cases. There are several unsolved problems related to the friendly numbers.

In spite of the similarity in name, there is no specific relationship between the friendly numbers and the amicable numbers or the sociable numbers, although the definitions of the latter two also involve the divisor function.

Examples

Blue numbers are proved friendly (sequence A074902 in the OEIS), red numbers are proved solitary (sequence A095739 in the OEIS), numbers n such that n and are coprime (sequence A014567 in the OEIS) are not coloured here, though they are known to be solitary. Other numbers have unknown status and are yellow.

| n | n | n | n | |||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 37 | 38 | 38/37 | 73 | 74 | 74/73 | 109 | 110 | 110/109 | |||

| 2 | 3 | 3/2 | 38 | 60 | 30/19 | 74 | 114 | 57/37 | 110 | 216 | 108/55 | |||

| 3 | 4 | 4/3 | 39 | 56 | 56/39 | 75 | 124 | 124/75 | 111 | 152 | 152/111 | |||

| 4 | 7 | 7/4 | 40 | 90 | 9/4 | 76 | 140 | 35/19 | 112 | 248 | 31/14 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 6/5 | 41 | 42 | 42/41 | 77 | 96 | 96/77 | 113 | 114 | 114/113 | |||

| 6 | 12 | 2 | 42 | 96 | 16/7 | 78 | 168 | 28/13 | 114 | 240 | 40/19 | |||

| 7 | 8 | 8/7 | 43 | 44 | 44/43 | 79 | 80 | 80/79 | 115 | 144 | 144/115 | |||

| 8 | 15 | 15/8 | 44 | 84 | 21/11 | 80 | 186 | 93/40 | 116 | 210 | 105/58 | |||

| 9 | 13 | 13/9 | 45 | 78 | 26/15 | 81 | 121 | 121/81 | 117 | 182 | 14/9 | |||

| 10 | 18 | 9/5 | 46 | 72 | 36/23 | 82 | 126 | 63/41 | 118 | 180 | 90/59 | |||

| 11 | 12 | 12/11 | 47 | 48 | 48/47 | 83 | 84 | 84/83 | 119 | 144 | 144/119 | |||

| 12 | 28 | 7/3 | 48 | 124 | 31/12 | 84 | 224 | 8/3 | 120 | 360 | 3 | |||

| 13 | 14 | 14/13 | 49 | 57 | 57/49 | 85 | 108 | 108/85 | 121 | 133 | 133/121 | |||

| 14 | 24 | 12/7 | 50 | 93 | 93/50 | 86 | 132 | 66/43 | 122 | 186 | 93/61 | |||

| 15 | 24 | 8/5 | 51 | 72 | 24/17 | 87 | 120 | 40/29 | 123 | 168 | 56/41 | |||

| 16 | 31 | 31/16 | 52 | 98 | 49/26 | 88 | 180 | 45/22 | 124 | 224 | 56/31 | |||

| 17 | 18 | 18/17 | 53 | 54 | 54/53 | 89 | 90 | 90/89 | 125 | 156 | 156/125 | |||

| 18 | 39 | 13/6 | 54 | 120 | 20/9 | 90 | 234 | 13/5 | 126 | 312 | 52/21 | |||

| 19 | 20 | 20/19 | 55 | 72 | 72/55 | 91 | 112 | 16/13 | 127 | 128 | 128/127 | |||

| 20 | 42 | 21/10 | 56 | 120 | 15/7 | 92 | 168 | 42/23 | 128 | 255 | 255/128 | |||

| 21 | 32 | 32/21 | 57 | 80 | 80/57 | 93 | 128 | 128/93 | 129 | 176 | 176/129 | |||

| 22 | 36 | 18/11 | 58 | 90 | 45/29 | 94 | 144 | 72/47 | 130 | 252 | 126/65 | |||

| 23 | 24 | 24/23 | 59 | 60 | 60/59 | 95 | 120 | 24/19 | 131 | 132 | 132/131 | |||

| 24 | 60 | 5/2 | 60 | 168 | 14/5 | 96 | 252 | 21/8 | 132 | 336 | 28/11 | |||

| 25 | 31 | 31/25 | 61 | 62 | 62/61 | 97 | 98 | 98/97 | 133 | 160 | 160/133 | |||

| 26 | 42 | 21/13 | 62 | 96 | 48/31 | 98 | 171 | 171/98 | 134 | 204 | 102/67 | |||

| 27 | 40 | 40/27 | 63 | 104 | 104/63 | 99 | 156 | 52/33 | 135 | 240 | 16/9 | |||

| 28 | 56 | 2 | 64 | 127 | 127/64 | 100 | 217 | 217/100 | 136 | 270 | 135/68 | |||

| 29 | 30 | 30/29 | 65 | 84 | 84/65 | 101 | 102 | 102/101 | 137 | 138 | 138/137 | |||

| 30 | 72 | 12/5 | 66 | 144 | 24/11 | 102 | 216 | 36/17 | 138 | 288 | 48/23 | |||

| 31 | 32 | 32/31 | 67 | 68 | 68/67 | 103 | 104 | 104/103 | 139 | 140 | 140/139 | |||

| 32 | 63 | 63/32 | 68 | 126 | 63/34 | 104 | 210 | 105/52 | 140 | 336 | 12/5 | |||

| 33 | 48 | 16/11 | 69 | 96 | 32/23 | 105 | 192 | 64/35 | 141 | 192 | 64/47 | |||

| 34 | 54 | 27/17 | 70 | 144 | 72/35 | 106 | 162 | 81/53 | 142 | 216 | 108/71 | |||

| 35 | 48 | 48/35 | 71 | 72 | 72/71 | 107 | 108 | 108/107 | 143 | 168 | 168/143 | |||

| 36 | 91 | 91/36 | 72 | 195 | 65/24 | 108 | 280 | 70/27 | 144 | 403 | 403/144 |

As another example, 30 and 140 form a friendly pair, because 30 and 140 have the same abundancy:

The numbers 2480, 6200 and 40640 are also members of this club, as they each have an abundancy equal to 12/5.

For an example of odd numbers being friendly, consider 135 and 819 (abundancy 16/9). There are also cases of even being friendly to odd, like 42 and 544635 (abundancy 16/7).

A perfect square can be friendly, for instance both 693479556 (the square of 26334) and 8640 have abundancy 127/36 (this example is due to Dean Hickerson).

Solitary numbers

A number that belongs to a singleton club, because no other number is friendly with it, is a solitary number. All prime numbers are known to be solitary, as are powers of prime numbers. More generally, if the numbers n and σ(n) are coprime – meaning that the greatest common divisor of these numbers is 1, so that σ(n)/n is an irreducible fraction – then the number n is solitary (sequence A014567 in the OEIS). For a prime number p we have σ(p) = p + 1, which is coprime with p.

No general method is known for determining whether a number is friendly or solitary. The smallest number whose classification is unknown (as of 2009) is 10; it is conjectured to be solitary; if not, its smallest friend is a fairly large number, like the status for the number 24, although 24 is friendly, its smallest friend is 91,963,648.

Large clubs

It is an open problem whether there are infinitely large clubs of mutually friendly numbers. The perfect numbers form a club, and it is conjectured that there are infinitely many perfect numbers (at least as many as there are Mersenne primes), but no proof is known. As of February 2016[update], 49 perfect numbers are known, the largest of which has more than 44 million digits in decimal notation. There are clubs with more known members, in particular those formed by multiply perfect numbers, which are numbers whose abundancy is an integer. As of early 2013, the club of friendly numbers with abundancy equal to 9 has 2094 known members.[1] Although some are known to be quite large, clubs of multiply perfect numbers (excluding the perfect numbers themselves) are conjectured to be finite.

Notes

- ^ Flammenkamp, Achim. "The Multiply Perfect Numbers Page". Retrieved 2008-04-20.