Genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules by which information encoded within genetic material (DNA or mRNA sequences) is translated into proteins by living cells. Biological decoding is accomplished by the ribosome, which links amino acids in an order specified by mRNA, using transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules to carry amino acids and to read the mRNA three nucleotides at a time. The genetic code is highly similar among all organisms and can be expressed in a simple table with 64 entries.

The code defines how sequences of these nucleotide triplets, called codons, specify which amino acid will be added next during protein synthesis. With some exceptions,[1] a three-nucleotide codon in a nucleic acid sequence specifies a single amino acid. Because the vast majority of genes are encoded with exactly the same code (see the RNA codon table), this particular code is often referred to as the canonical or standard genetic code, or simply the genetic code, though in fact some variant codes have evolved. For example, protein synthesis in human mitochondria relies on a genetic code that differs from the standard genetic code.

While the genetic code determines the protein sequence for a given coding region, other genomic regions can influence when and where these proteins are produced.

Discovery

Serious efforts to understand how proteins are encoded began after the structure of DNA was discovered by James Watson and Francis Crick, who used the experimental evidence of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, among others. George Gamow postulated that sets of three bases must be employed to encode the 20 standard amino acids used by living cells to build proteins. With four different nucleotides, a code of 2 nucleotides would allow for only a maximum of 42 or 16 amino acids. A code of 3 nucleotides could code for a maximum of 43 or 64 amino acids.[2]

The Crick, Brenner et al. experiment first demonstrated that codons consist of three DNA bases; Marshall Nirenberg and Heinrich J. Matthaei were the first to elucidate the nature of a codon in 1961 at the National Institutes of Health. They used a cell-free system to translate a poly-uracil RNA sequence (i.e., UUUUU...) and discovered that the polypeptide that they had synthesized consisted of only the amino acid phenylalanine.[3] They thereby deduced that the codon UUU specified the amino acid phenylalanine. This was followed by experiments in Severo Ochoa's laboratory that demonstrated that the poly-adenine RNA sequence (AAAAA...) coded for the polypeptide poly-lysine[4] and that the poly-cytosine RNA sequence (CCCCC...) coded for the polypeptide poly-proline.[5] Therefore the codon AAA specified the amino acid lysine, and the codon CCC specified the amino acid proline. Using different copolymers most of the remaining codons were then determined. Subsequent work by Har Gobind Khorana identified the rest of the genetic code. Shortly thereafter, Robert W. Holley determined the structure of transfer RNA (tRNA), the adapter molecule that facilitates the process of translating RNA into protein. This work was based upon earlier studies by Severo Ochoa, who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1959 for his work on the enzymology of RNA synthesis.[6]

Extending this work, Nirenberg and Philip Leder revealed the triplet nature of the genetic code and deciphered the codons of the standard genetic code. In these experiments, various combinations of mRNA were passed through a filter that contained ribosomes, the components of cells that translate RNA into protein. Unique triplets promoted the binding of specific tRNAs to the ribosome. Leder and Nirenberg were able to determine the sequences of 54 out of 64 codons in their experiments.[7] In 1968, Khorana, Holley and Nirenberg received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work.[8]

Salient features

Sequence reading frame

A codon is defined by the initial nucleotide from which translation starts. For example, the string GGGAAACCC, if read from the first position, contains the codons GGG, AAA, and CCC; and, if read from the second position, it contains the codons GGA and AAC; if read starting from the third position, GAA and ACC. Every sequence can, thus, be read in three reading frames, each of which will produce a different amino acid sequence (in the given example, Gly-Lys-Pro, Gly-Asn, or Glu-Thr, respectively). With double-stranded DNA, there are six possible reading frames, three in the forward orientation on one strand and three reverse on the opposite strand.[9]: 330 The actual frame in which a protein sequence is translated is defined by a start codon, usually the first AUG codon in the mRNA sequence.

Start/stop codons

Translation starts with a chain initiation codon or start codon. Unlike stop codons, the codon alone is not sufficient to begin the process. Nearby sequences such as the Shine-Dalgarno sequence in E. coli and initiation factors are also required to start translation. The most common start codon is AUG, which is read as methionine or, in bacteria, as formylmethionine. Alternative start codons depending on the organism include "GUG" or "UUG"; these codons normally represent valine and leucine, respectively, but as start codons they are translated as methionine or formylmethionine.[10]

The three stop codons have been given names: UAG is amber, UGA is opal (sometimes also called umber), and UAA is ochre. "Amber" was named by discoverers Richard Epstein and Charles Steinberg after their friend Harris Bernstein, whose last name means "amber" in German.[11] The other two stop codons were named "ochre" and "opal" in order to keep the "color names" theme. Stop codons are also called "termination" or "nonsense" codons. They signal release of the nascent polypeptide from the ribosome because there is no cognate tRNA that has anticodons complementary to these stop signals, and so a release factor binds to the ribosome instead.[12]

Effect of mutations

During the process of DNA replication, errors occasionally occur in the polymerization of the second strand. These errors, called mutations, can have an impact on the phenotype of an organism, especially if they occur within the protein coding sequence of a gene. Error rates are usually very low—1 error in every 10–100 million bases—due to the "proofreading" ability of DNA polymerases.[14][15]

Missense mutations and nonsense mutations are examples of point mutations, which can cause genetic diseases such as sickle-cell disease and thalassemia respectively.[16][17][18] Clinically important missense mutations generally change the properties of the coded amino acid residue between being basic, acidic, polar or non-polar, whereas nonsense mutations result in a stop codon.[9]: 266

Mutations that disrupt the reading frame sequence by indels (insertions or deletions) of a non-multiple of 3 nucleotide bases are known as frameshift mutations. These mutations usually result in a completely different translation from the original, and are also very likely to cause a stop codon to be read, which truncates the creation of the protein.[19] These mutations may impair the function of the resulting protein, and are thus rare in in vivo protein-coding sequences. One reason inheritance of frameshift mutations is rare is that, if the protein being translated is essential for growth under the selective pressures the organism faces, absence of a functional protein may cause death before the organism is viable.[20] Frameshift mutations may result in severe genetic diseases such as Tay-Sachs disease.[21]

Although most mutations that change protein sequences are harmful or neutral, some mutations have a benefical effect on an organism.[22] These mutations may enable the mutant organism to withstand particular environmental stresses better than wild-type organisms, or reproduce more quickly. In these cases a mutation will tend to become more common in a population through natural selection.[23] Viruses that use RNA as their genetic material have rapid mutation rates,[24] which can be an advantage, since these viruses will evolve constantly and rapidly, and thus evade the defensive responses of e.g. the human immune system.[25] In large populations of asexually reproducing organisms, for example, E. coli, multiple beneficial mutations may co-occur. This phenomenon is called clonal interference and causes competition among the mutations.[26]

Degeneracy

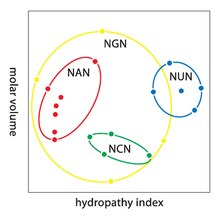

Degeneracy is the redundancy of the genetic code. The genetic code has redundancy but no ambiguity (see the codon tables below for the full correlation). For example, although codons GAA and GAG both specify glutamic acid (redundancy), neither of them specifies any other amino acid (no ambiguity). The codons encoding one amino acid may differ in any of their three positions. For example the amino acid leucine is specified by YUR or CUN (UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA, or CUG) codons (difference in the first or third position indicated using IUPAC notation), while the amino acid serine is specified by UCN or AGY (UCA, UCG, UCC, UCU, AGU, or AGC) codons (difference in the first, second, or third position).[27]: 521–522 A practical consequence of redundancy is that errors in the third position of the triplet codon cause only a silent mutation or an error that would not affect the protein because the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity is maintained by equivalent substitution of amino acids; for example, a codon of NUN (where N = any nucleotide) tends to code for hydrophobic amino acids. NCN yields amino acid residues that are small in size and moderate in hydropathy; NAN encodes average size hydrophilic residues. The genetic code is so well-structured for hydropathy that a mathematical analysis (Singular Value Decomposition) of 12 variables (4 nucleotides x 3 positions) yields a remarkable correlation (C = 0.95) for predicting the hydropathy of the encoded amino acid directly from the triplet nucleotide sequence, without translation.[28][29] Note in the table, below, eight amino acids are not affected at all by mutations at the third position of the codon, whereas in the figure to the right, a mutation at the second position is likely to cause a radical change in the physicochemical properties of the encoded amino acid.

Transfer of information via the genetic code

The genome of an organism is inscribed in DNA, or, in the case of some viruses, RNA. The portion of the genome that codes for a protein or an RNA is called a gene. Those genes that code for proteins are composed of tri-nucleotide units called codons, each coding for a single amino acid. Each nucleotide sub-unit consists of a phosphate, a deoxyribose sugar, and one of the four nitrogenous nucleobases. The purine bases adenine (A) and guanine (G) are larger and consist of two aromatic rings. The pyrimidine bases cytosine (C) and thymine (T) are smaller and consist of only one aromatic ring. In the double-helix configuration, two strands of DNA are joined to each other by hydrogen bonds in an arrangement known as base pairing. These bonds almost always form between an adenine base on one strand and a thymine base on the other strand, or between a cytosine base on one strand and a guanine base on the other. This means that the number of A and T bases will be the same in a given double helix, as will the number of G and C bases.[27]: 102–117 In RNA, thymine (T) is replaced by uracil (U), and the deoxyribose is substituted by ribose.[27]: 127

Each protein-coding gene is transcribed into a molecule of the related RNA polymer. In prokaryotes, this RNA functions as messenger RNA or mRNA; in eukaryotes, the transcript needs to be processed to produce a mature mRNA. The mRNA is, in turn, translated on a ribosome into a chain of amino acids otherwise known as a polypeptide.[27]: Chp 12 The process of translation requires transfer RNAs which are covalently attached to a specific amino acid, guanosine triphosphate as an energy source, and a number of translation factors. tRNAs have anticodons complementary to the codons in an mRNA and can be covalently "charged" with specific amino acids at their 3' terminal CCA ends by enzymes known as aminoacyl tRNA synthetases, which have high specificity for both their cognate amino acid and tRNA. The high specificity of these enzymes is a major reason why the fidelity of protein translation is maintained.[27]: 464–469

There are 4³ = 64 different codon combinations possible with a triplet codon of three nucleotides; all 64 codons are assigned to either an amino acid or a stop signal. If, for example, an RNA sequence UUUAAACCC is considered and the reading frame starts with the first U (by convention, 5' to 3'), there are three codons, namely, UUU, AAA, and CCC, each of which specifies one amino acid. Therefore, this 9 base RNA sequence will be translated into an amino acid sequence that is three amino acids long.[27]: 521–539 A given amino acid may be encoded by between one and six different codon sequences. A comparison may be made using bioinformatics tools wherein the codon is similar to a word, which is the standard data "chunk" and a nucleotide is similar to a bit, in that it is the smallest unit. This allows for powerful comparisons across species as well as within organisms.

The standard genetic code is shown in the following tables. Table 1 shows which amino acid each of the 64 codons specifies. Table 2 shows which codons specify each of the 20 standard amino acids involved in translation. These are called forward and reverse codon tables, respectively. For example, the codon "AAU" represents the amino acid asparagine, and "UGU" and "UGC" represent cysteine (standard three-letter designations, Asn and Cys, respectively).[27]: 522

RNA codon table

| Amino-acid biochemical properties | Nonpolar | Polar | Basic | Acidic | Termination: stop codon |

| 1st base |

2nd base | 3rd base | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | C | A | G | ||||||

| U | UUU | (Phe/F) Phenylalanine | UCU | (Ser/S) Serine | UAU | (Tyr/Y) Tyrosine | UGU | (Cys/C) Cysteine | U |

| UUC | UCC | UAC | UGC | C | |||||

| UUA | (Leu/L) Leucine | UCA | UAA | Stop (Ochre)[B] | UGA | Stop (Opal)[B] | A | ||

| UUG[A] | UCG | UAG | Stop (Amber)[B] | UGG | (Trp/W) Tryptophan | G | |||

| C | CUU | CCU | (Pro/P) Proline | CAU | (His/H) Histidine | CGU | (Arg/R) Arginine | U | |

| CUC | CCC | CAC | CGC | C | |||||

| CUA | CCA | CAA | (Gln/Q) Glutamine | CGA | A | ||||

| CUG | CCG | CAG | CGG | G | |||||

| A | AUU | (Ile/I) Isoleucine | ACU | (Thr/T) Threonine | AAU | (Asn/N) Asparagine | AGU | (Ser/S) Serine | U |

| AUC | ACC | AAC | AGC | C | |||||

| AUA | ACA | AAA | (Lys/K) Lysine | AGA | (Arg/R) Arginine | A | |||

| AUG[A] | (Met/M) Methionine | ACG | AAG | AGG | G | ||||

| G | GUU | (Val/V) Valine | GCU | (Ala/A) Alanine | GAU | (Asp/D) Aspartic acid | GGU | (Gly/G) Glycine | U |

| GUC | GCC | GAC | GGC | C | |||||

| GUA | GCA | GAA | (Glu/E) Glutamic acid | GGA | A | ||||

| GUG[A] | GCG | GAG | GGG | G | |||||

- A Possible start codons in NCBI table 1. AUG is most common.[31] The two other start codons listed by table 1 (GUG and UUG) are rare in eukaryotes.[32] Prokaryotes have less strigent start codon requirements; they are described by NCBI table 11.

- B ^ ^ ^ The historical basis for designating the stop codons as amber, ochre and opal is described in an autobiography by Sydney Brenner[33] and in a historical article by Bob Edgar.[34]

| Amino acid | DNA codons | Compressed | Amino acid | DNA codons | Compressed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala, A | GCU, GCC, GCA, GCG | GCN | Ile, I | AUU, AUC, AUA | AUH | |

| Arg, R | CGU, CGC, CGA, CGG; AGA, AGG | CGN, AGR; or CGY, MGR |

Leu, L | CUU, CUC, CUA, CUG; UUA, UUG | CUN, UUR; or CUY, YUR | |

| Asn, N | AAU, AAC | AAY | Lys, K | AAA, AAG | AAR | |

| Asp, D | GAU, GAC | GAY | Met, M | AUG | ||

| Asn or Asp, B | AAU, AAC; GAU, GAC | RAY | Phe, F | UUU, UUC | UUY | |

| Cys, C | UGU, UGC | UGY | Pro, P | CCU, CCC, CCA, CCG | CCN | |

| Gln, Q | CAA, CAG | CAR | Ser, S | UCU, UCC, UCA, UCG; AGU, AGC | UCN, AGY | |

| Glu, E | GAA, GAG | GAR | Thr, T | ACU, ACC, ACA, ACG | ACN | |

| Gln or Glu, Z | CAA, CAG; GAA, GAG | SAR | Trp, W | UGG | ||

| Gly, G | GGU, GGC, GGA, GGG | GGN | Tyr, Y | UAU, UAC | UAY | |

| His, H | CAU, CAC | CAY | Val, V | GUU, GUC, GUA, GUG | GUN | |

| START | AUG, CUG, UUG | HUG | STOP | UAA, UGA, UAG | URA, UAR | |

DNA codon table

The DNA codon table is essentially identical to that for RNA, but with U replaced by T.

Variations to the standard genetic code

While slight variations on the standard code had been predicted earlier,[35] none were discovered until 1979, when researchers studying human mitochondrial genes discovered they used an alternative code. Many slight variants have been discovered since then,[36] including various alternative mitochondrial codes,[37] and small variants such as translation of the codon UGA as tryptophan in Mycoplasma species, and translation of CUG as a serine rather than a leucine in yeasts of the "CTG clade" (Candida albicans is member of this group).[38][39][40] Because viruses must use the same genetic code as their hosts, modifications to the standard genetic code could interfere with the synthesis or functioning of viral proteins. However, some viruses (such as totiviruses) have adapted to the genetic code modification of the host.[41] In bacteria and archaea, GUG and UUG are common start codons, but in rare cases, certain proteins may use alternative start codons not normally used by that species.[36]

In certain proteins, non-standard amino acids are substituted for standard stop codons, depending on associated signal sequences in the messenger RNA. For example, UGA can code for selenocysteine and UAG can code for pyrrolysine. Selenocysteine is now viewed as the 21st amino acid, and pyrrolysine is viewed as the 22nd.[36] Unlike selenocysteine, pyrrolysine encoded UAG is translated with the participation of a dedicated aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase.[42] Both selenocysteine and pyrrolysine may be present in the same organism.[43] Although the genetic code is normally fixed in an organism the achaeal prokaryote Acetohalobium arabaticum can expand its genetic code from 20 to 21 amino acids (by including pyrrolysine) under different conditions of growth.[44]

Despite these differences, all known naturally-occurring codes are very similar to each other, and the coding mechanism is the same for all organisms: three-base codons, tRNA, ribosomes, reading the code in the same direction and translating the code three letters at a time into sequences of amino acids.

Predicting the genetic code

The genetic code used by a genome can be predicted by identifying the genes encoded on that genome, and comparing the codons on the DNA to the amino acids in homologous proteins in other genomes. The evolutionary conservation of protein sequences makes it possible to predict the amino acid translation for each codon as the one that is most often aligned to that codon. The program FACIL [45] allows the automated prediction of the genetic code, searching which amino acids in homologous protein domains are most often aligned to every codon. The resulting amino acid probabilities for each codon are displayed in a genetic code logo, that also shows the support for a stop codon.

Expanded genetic code

Since 2001, 40 non-natural amino acids have been added into protein by creating a unique codon (recoding) and a corresponding transfer-RNA:aminoacyl – tRNA-synthetase pair to encode it with diverse physicochemical and biological properties in order to be used as a tool to exploring protein structure and function or to create novel or enhanced proteins.[45][46]

H. Murakami and M. Sisido have extended some codons to have four and five bases. Steven A. Benner constructed a functional 65th (in vivo) codon.[47]

Origin

If amino acids were randomly assigned to triplet codons, then there would be 1.5 x 1084 possible genetic codes to choose from[48]: 163 . However, the genetic code used by all known forms of life is nearly universal with few minor variations. One could ask: Has all life on Earth descended from a single bacterium that mutated to make the final optimization in the universal genetic code? Many hypotheses on the evolutionary origins of the universal genetic code have been proposed.

Four themes run through the many hypotheses about the evolution of the genetic code:[49]

- Chemical principles govern specific RNA interaction with amino acids. Experiments with aptamers showed that some amino acids have a selective chemical affinity for the base triplets that code for them.[50] Recent experiments show that of the 8 amino acids tested, 6 show some RNA triplet-amino acid association.[48]: 170 [51]

- Biosynthetic expansion. The standard modern genetic code grew from a simpler earlier code through a process of "biosynthetic expansion". Here the idea is that primordial life "discovered" new amino acids (for example, as by-products of metabolism) and later incorporated some of these into the machinery of genetic coding. Although much circumstantial evidence has been found to suggest that fewer different amino acids were used in the past than today,[52] precise and detailed hypotheses about which amino acids entered the code in what order have proved far more controversial.[53][54]

- Natural selection has led to codon assignments of the genetic code that minimize the effects of mutations.[55] A recent hypothesis[56] suggests that the triplet code was derived from codes that used longer than triplet codons (such as quadruplet codons). Longer than triplet decoding would have higher degree of codon redundancy and would be more error resistant than the triplet decoding. This feature could allow accurate decoding in the absence of highly complex translational machinery such as the ribosome and before cells began making ribosomes.

- Information channels: Information-theoretic approaches model the process of translating the genetic code into corresponding amino acids as an error-prone information channel.[57] The inherent noise (that is, the error) in the channel poses the organism with a fundamental question: how can a genetic code be constructed to withstand the impact of noise[58] while accurately and efficiently translating information? These “rate-distortion” models[59] suggest that the genetic code originated as a result of the interplay of the three conflicting evolutionary forces: the needs for diverse amino-acids,[60] for error-tolerance[55] and for minimal cost of resources. The code emerges at a coding transition when the mapping of codons to amino-acids becomes nonrandom. The emergence of the code is governed by the topology defined by the probable errors and is related to the map coloring problem.[61]

Transfer RNA molecules appear to have evolved before modern aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, so the latter cannot be part of the explanation of its patterns.[62]

Models encompassing aspects of two or more of the above themes have also been explored. For example, models based on signaling games combine elements of game theory, natural selection and information channels. Such models have been used to suggest that the first polypeptides were likely short and had some use other than enzymatic function. Game theoretic models have also suggested that the organization of RNA strings into cells may have been necessary to prevent "deceptive" use of the genetic code, i.e. preventing the ancient equivalent of viruses from overwhelming the RNA world.[63]

The distribution of codon assignments in the genetic code is nonrandom.[64] For example, the genetic code clusters certain amino acid assignments. Amino acids that share the same biosynthetic pathway tend to have the same first base in their codons.[65] Amino acids with similar physical properties tend to have similar codons,[66][67] reducing the problems caused by point mutations and mistranslations.[64] A robust hypothesis for the origin of genetic code should also address or predict the following gross features of the codon table:[68]

- absence of codons for D-amino acids

- secondary codon patterns for some amino acids

- confinement of synonymous positions to third position

- limitation to 20 amino acids instead of a number closer to 64

- relation of stop codon patterns to amino acid coding patterns

See also

References

- ^ Turanov AA, Lobanov AV, Fomenko DE, Morrison HG, Sogin ML, Klobutcher LA, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN (January 2009). "Genetic code supports targeted insertion of two amino acids by one codon". Science. 323 (5911): 259–61. doi:10.1126/science.1164748. PMC 3088105. PMID 19131629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crick, Francis (1988). "Chapter 8: The genetic code". What mad pursuit: a personal view of scientific discovery. New York: Basic Books. pp. 89–101. ISBN 0-465-09138-5.

- ^ Marshall W. Nirenberg and J. Heinrich Matthaei (October 1961). "The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon naturally occurring or synthetic polyribonucleotides". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 47 (10): 1588–1602. PMC 223178. PMID 14479932.

- ^ Gardner RS, Wahba AJ, Basilio C, Miller RS, Lengyel P, Speyer JF (December 1962). "Synthetic polynucleotides and the amino acid code. VII". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 48 (12): 2087–94. Bibcode:1962PNAS...48.2087G. doi:10.1073/pnas.48.12.2087. PMC 221128. PMID 13946552.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wahba AJ, Gardner RS, Basilio C, Miller RS, Speyer JF, Lengyel P (January 1963). "Synthetic polynucleotides and the amino acid code. VIII". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 49 (1): 116–22. Bibcode:1963PNAS...49..116W. doi:10.1073/pnas.49.1.116. PMC 300638. PMID 13998282.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959" (Press release). The Royal Swedish Academy of Science. 1959. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 was awarded jointly to Severo Ochoa and Arthur Kornberg 'for their discovery of the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid'.

- ^ Nirenberg M, Leder P, Bernfield M, Brimacombe R, Trupin J, Rottman F, O'Neal C (May 1965). "RNA codewords and protein synthesis, VII. On the general nature of the RNA code". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 53 (5): 1161–8. Bibcode:1965PNAS...53.1161N. doi:10.1073/pnas.53.5.1161. PMC 301388. PMID 5330357.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968" (Press release). The Royal Swedish Academy of Science. 1968. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968 was awarded jointly to Robert W. Holley, Har Gobind Khorana and Marshall W. Nirenberg 'for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis'.

- ^ a b Pamela K. Mulligan; King, Robert C.; Stansfield, William D. (2006 pages = 608). A dictionary of genetics. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-530761-5.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Missing pipe in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Touriol C, Bornes S, Bonnal S, Audigier S, Prats H, Prats AC, Vagner S (2003). "Generation of protein isoform diversity by alternative initiation of translation at non-AUG codons". Biol. Cell. 95 (3–4): 169–78. doi:10.1016/S0248-4900(03)00033-9. PMID 12867081.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edgar B (2004). "The genome of bacteriophage T4: an archeological dig". Genetics. 168 (2): 575–82. PMC 1448817. PMID 15514035.

- ^ Maloy S (2003-11-29). "How nonsense mutations got their names". Microbial Genetics Course. San Diego State University. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ^ References for the image are found in Wikimedia Commons page at: Commons:File:Notable mutations.svg#References.

- ^ Griffiths, Anthony J. F.; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Suzuki, David T.; Lewontin, Richard C.; Gelbart, eds. (2000). "Spontaneous mutations". An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (7th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3520-2.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Freisinger, E; Grollman, AP; Miller, H; Kisker, C (2004). "Lesion (in)tolerance reveals insights into DNA replication fidelity". The EMBO Journal. 23 (7): 1494–505. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600158. PMC 391067. PMID 15057282.

- ^ (Boillée 2006, p. 39)

- ^ Chang JC, Kan YW (June 1979). "beta 0 thalassemia, a nonsense mutation in man". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76 (6): 2886–9. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.2886C. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.6.2886. PMC 383714. PMID 88735.

- ^ Boillée S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW (October 2006). "ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors". Neuron. 52 (1): 39–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. PMID 17015226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Isbrandt D, Hopwood JJ, von Figura K, Peters C (1996). "Two novel frameshift mutations causing premature stop codons in a patient with the severe form of Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome". Hum. Mutat. 7 (4): 361–3. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)7:4<361::AID-HUMU12>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 8723688.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crow JF (1993). "How much do we know about spontaneous human mutation rates?". Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 21 (2): 122–9. doi:10.1002/em.2850210205. PMID 8444142.

- ^ Lewis, Ricki (2005). Human Genetics: Concepts and Applications (6th ed.). Boston, Mass: McGraw Hill. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0-07-111156-5.

- ^ Sawyer SA, Parsch J, Zhang Z, Hartl DL (2007). "Prevalence of positive selection among nearly neutral amino acid replacements in Drosophila". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (16): 6504–10. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6504S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701572104. PMC 1871816. PMID 17409186.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bridges KR (2002). "Malaria and the Red Cell". Harvard.

- ^ Drake JW, Holland JJ (1999). "Mutation rates among RNA viruses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (24): 13910–3. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9613910D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.24.13910. PMC 24164. PMID 10570172.

- ^ Holland J, Spindler K, Horodyski F, Grabau E, Nichol S, VandePol S (1982). "Rapid evolution of RNA genomes". Science. 215 (4540): 1577–85. Bibcode:1982Sci...215.1577H. doi:10.1126/science.7041255. PMID 7041255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arjan J, de Visser DM, Rozen DE (2006). "Clonal Interference and the Periodic Selection of New Beneficial Mutations in Escherichia coli". Genetics, the Genetics Society of America. 172 (4): 2093–2100. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.052373. PMC 1456385. PMID 16489229.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Watson JD, Baker TA, Bell SP, Gann A, Levine M, Oosick R. (2008). Molecular Biology of the Gene. San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-9592-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yang et al. (1990) in Michel-Beyerle, M. E., ed. Reaction centers of photosynthetic bacteria: Feldafing-II-Meeting 6. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 209–18. ISBN 3-540-53420-2.

- ^ Füllen G, Youvan DC (1994). "Genetic Algorithms and Recursive Ensemble Mutagenesis in Protein Engineering". Complexity International 1.

- ^ Elzanowski A, Ostell J (7 January 2019). "The Genetic Codes". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Nakamoto T (March 2009). "Evolution and the universality of the mechanism of initiation of protein synthesis". Gene. 432 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.001. PMID 19056476.

- ^ Asano, K (2014). "Why is start codon selection so precise in eukaryotes?". Translation (Austin, Tex.). 2 (1): e28387. doi:10.4161/trla.28387. PMID 26779403.

- ^ Brenner S. A Life in Science (2001) Published by Biomed Central Limited ISBN 0-9540278-0-9 see pages 101-104

- ^ Edgar B (2004). "The genome of bacteriophage T4: an archeological dig". Genetics. 168 (2): 575–82. PMC 1448817. PMID 15514035. see pages 580-581

- ^ Crick FHC, Orgel LE (1973). "Directed panspermia". Icarus. 19 (3): 341–6. Bibcode:1973Icar...19..341C. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(73)90110-3.

It is a little surprising that organisms with somewhat different codes do not coexist.

(p. 344) (Further discussion) - ^ a b c Elzanowski A, Ostell J (2008-04-07). "The Genetic Codes". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ^ Jukes TH, Osawa S (December 1990). "The genetic code in mitochondria and chloroplasts". Experientia. 46 (11–12): 1117–26. doi:10.1007/BF01936921. PMID 2253709.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, David A (1 January 2006). "A fungal phylogeny based on 42 complete genomes derived from supertree and combined gene analysis". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 6: 99. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-99. PMC 1679813. PMID 17121679.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Santos, M.A.; Tuite, M.F. (1995). "The CUG codon is decoded in vivo as serine and not leucine in Candida albicans". Nucleic Acids Research. 23 (9): 1481–6. doi:10.1093/nar/23.9.1481. PMC 306886. PMID 7784200.

- ^ Butler, G.; Rasmussen, MD; Lin, MF; Santos, MA; Sakthikumar, S; Munro, CA; Rheinbay, E; Grabherr, M; Forche, A; et al. (2009). "Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes". Nature. 459 (7247): 657–62. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..657B. doi:10.1038/nature08064. PMC 2834264. PMID 19465905.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first13=missing|last13=(help);|first14=missing|last14=(help);|first15=missing|last15=(help);|first16=missing|last16=(help);|first17=missing|last17=(help);|first18=missing|last18=(help);|first19=missing|last19=(help);|first20=missing|last20=(help);|first21=missing|last21=(help);|first22=missing|last22=(help);|first23=missing|last23=(help);|first24=missing|last24=(help);|first25=missing|last25=(help);|first26=missing|last26=(help);|first27=missing|last27=(help);|first28=missing|last28=(help);|first29=missing|last29=(help);|first30=missing|last30=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Taylor, Derek J. (2013). "Virus-host co-evolution under a modified nuclear genetic code". PeerJ. 1: e50. doi:10.7717/peerj.50. PMC 3628385. PMID 23638388.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); no-break space character in|coauthors=at position 56 (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16256420, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16256420instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15788401, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15788401instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23185002, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23185002instead. - ^ a b Bas E. Dutilh, Rasa Jurgelenaite, Radek Szklarczyk, Sacha A.F.T. van Hijum, Harry R. Harhangi, Markus Schmid, Bart de Wild, Kees-Jan Françoijs, Hendrik G. Stunnenberg, Marc Strous, Mike S.M. Jetten, Huub J.M. Op den Camp and Martijn A. Huynen (July 2011). "FACIL: fast and accurate genetic code inference and logo". Bioinformatics. 27 (6): 1929–1933. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr316. PMC 3129529. PMID 21653513.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid16260173" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Wang Q, Parrish AR, Wang L (March 2009). "Expanding the genetic code for biological studies". Chem. Biol. 16 (3): 323–36. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.03.001. PMC 2696486. PMID 19318213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simon M (2005). Emergent computation: emphasizing bioinformatics. New York: AIP Press/Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-387-22046-1.

- ^ a b Yarus M (2010). Life from an RNA World: The Ancestor Within. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 163. ISBN 0-674-05075-4.

- ^ Knight RD, Freeland SJ, Landweber LF (June 1999). "Selection, history and chemistry: the three faces of the genetic code". Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 (6): 241–7. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01392-4. PMID 10366854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Knight RD, Landweber LF (September 1998). "Rhyme or reason: RNA-arginine interactions and the genetic code". Chem. Biol. 5 (9): R215–20. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(98)90001-1. PMID 9751648.

- ^ Yarus M, Widmann JJ, Knight R (November 2009). "RNA-amino acid binding: a stereochemical era for the genetic code". J. Mol. Evol. 69 (5): 406–29. doi:10.1007/s00239-009-9270-1. PMID 19795157.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brooks DJ, Fresco JR, Lesk AM, Singh M (October 2002). "Evolution of amino acid frequencies in proteins over deep time: inferred order of introduction of amino acids into the genetic code". Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 (10): 1645–55. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003988. PMID 12270892.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Amirnovin R (May 1997). "An analysis of the metabolic theory of the origin of the genetic code". J. Mol. Evol. 44 (5): 473–6. doi:10.1007/PL00006170. PMID 9115171.

- ^ Ronneberg TA, Landweber LF, Freeland SJ (December 2000). "Testing a biosynthetic theory of the genetic code: fact or artifact?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (25): 13690–5. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9713690R. doi:10.1073/pnas.250403097. PMC 17637. PMID 11087835.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Freeland SJ, Wu T, Keulmann N (October 2003). "The case for an error minimizing standard genetic code". Orig Life Evol Biosph. 33 (4–5): 457–77. doi:10.1023/A:1025771327614. PMID 14604186.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baranov PV, Venin M, Provan G (2009). Gemmell, Neil John (ed.). "Codon size reduction as the origin of the triplet genetic code". PLoS ONE. 4 (5): e5708. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5708B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005708. PMC 2682656. PMID 19479032.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tlusty T (Nov 2007). "A model for the emergence of the genetic code as a transition in a noisy information channel". J Theor Biol. 249 (2): 331–42. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.07.029. PMID 17826800.

- ^ Sonneborn TM (1965). Evolving genes and proteins. New York: Academic Press. pp. 377–397.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Tlusty T (Feb 2008). "Rate-distortion scenario for the emergence and evolution of noisy molecular codes". Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 (4): 048101. arXiv:1007.4149. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100d8101T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.048101. PMID 18352335.

- ^ Sella G, Ardell D (Jul 2006). "The coevolution of genes and genetic codes: Crick's frozen accident revisited". J. Mol. Evol. 63 (3): 297–313. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0176-7. PMID 16838217.

- ^ Tlusty T (Sep 2010). "A colorful origin for the genetic code: Information theory, statistical mechanics and the emergence of molecular codes". Phys. Life. Rev. 7 (3): 362–376. arXiv:1007.3906. Bibcode:2010PhLRv...7..362T. doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2010.06.002. PMID 20558115.

- ^ Ribas de Pouplana L, Turner RJ, Steer BA, Schimmel P (September 1998). "Genetic code origins: tRNAs older than their synthetases?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (19): 11295–300. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9511295D. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.19.11295. PMC 21636. PMID 9736730.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jee J, Sundstrom A, Massey SE, Mishra B (2013). "What can information-asymmetric games tell us about the context of Crick's "Frozen Accident?"". J R Soc Interface. 10 (88): 20130614. doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.0614. PMC 3785830. PMID 23985735.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Freeland SJ, Hurst LD (September 1998). "The genetic code is one in a million". J. Mol. Evol. 47 (3): 238–48. doi:10.1007/PL00006381. PMID 9732450.

- ^ Taylor FJ, Coates D (1989). "The code within the codons". BioSystems. 22 (3): 177–87. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(89)90059-2. PMID 2650752.

- ^ Di Giulio M (October 1989). "The extension reached by the minimization of the polarity distances during the evolution of the genetic code". J. Mol. Evol. 29 (4): 288–93. doi:10.1007/BF02103616. PMID 2514270.

- ^ Wong JT (February 1980). "Role of minimization of chemical distances between amino acids in the evolution of the genetic code". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 (2): 1083–6. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.1083W. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.2.1083. PMC 348428. PMID 6928661.

- ^ Erives A (2011). "A Model of Proto-Anti-Codon RNA Enzymes Requiring L-Amino Acid Homochirality". J Molecular Evolution. 73 (1–2): 10–22. doi:10.1007/s00239-011-9453-4. PMC 3223571. PMID 21779963.

Further reading

- Griffiths, Anthony J. F.; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Suzuki, David T.; Lewontin, Richard C.; Gelbart, William M. (1999). An Introduction to genetic analysis (7th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3771-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lodish, Harvey F.; Berk, Arnold; Zipursky, S. Lawrence; Matsudaira, Paul; Baltimore, David; Darnell, James E. (2000). Molecular cell biology (4th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3706-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- The Genetic Codes → Genetic Code Tables

- The Codon Usage Database → Codon frequency tables for many organisms

- History of deciphering the genetic code

- American Scientist: Ode to the code (Origin)

- Alphabet of Life (Origin)

- Symmetries in the genetic code