Great Mosque of Xi'an

| Great Mosque of Xi'an | |

|---|---|

西安大清真寺 | |

Second courtyard of the Great Mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Xi'an, China |

| Geographic coordinates | 34°15′48″N 108°56′11″E / 34.2633°N 108.9364°E |

The Great Mosque of Xi'an (Chinese: 西安大清真寺; pinyin: Xīān Dà Qīngzhēnsì) is the largest mosque in China.[1]: 128 An active place of worship within Xi'an Muslim Quarter, this courtyard complex is also a popular tourist site. The majority of the mosque was built during the early Ming dynasty.[2]: 121 It now houses more than twenty buildings in its five courtyards, and covers 12,000 square meters.

Etymology

The mosque is also known as the Huajue Mosque (Chinese: 化觉巷清真寺; pinyin: Huàjué Xiàng Qīngzhēnsì), for its location on 30 Huajue Lane. It is sometimes called the Great Eastern Mosque (Chinese: 东大寺; pinyin: Dōng Dàsì), as well, because it sits east of another of Xi’an’s oldest mosques, Daxuexi Mosque (Chinese: 大学习巷清真寺; pinyin: Dàxuéxí Xiàng Qīngzhēnsì).

History

The mosque was constructed during the Hongwu reign of the Ming dynasty, with further additions during the Qing dynasty.[2]: 121 Previous religious complexes (Tanmingsi and Huihui Wanshansi) are known to have stood on the same site, dating to as early as the Tang dynasty.[2]: 121

In 1956, the mosque was declared a Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the Shaanxi Province Level, and was later promoted to a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level in 1988. The mosque is still used as a place of worship by Chinese Muslims, primarily Hui people, today.

Architecture

The mosque is a walled complex of five courtyards, with the prayer hall located in the fourth courtyard. Each courtyard contains a central monument, such as a gate, and is lined with greenery as well as subsidiary buildings. The first courtyard, for instance, contains a Qing dynasty monumental gate, while the fourth courtyard houses the Phoenix Pavilion, a hexagonal gazebo. Many walls throughout the complex are filled with inscriptions of birds, plants, objects, and text, both in Chinese and Arabic. Stone steles record repairs to the mosque and feature calligraphic works. In the second courtyard, two steles feature scripts of the calligrapher Mi Fu of the Song dynasty and Dong Qichang, a calligrapher of the Ming dynasty.[citation needed]

Overall, the mosque's architecture combines a traditional Chinese architectural form with Islamic functionality. For example, whereas traditional Chinese buildings align along a north-south axis in accordance with feng shui, the mosque is directed west towards Mecca, while still conforming to the axes of the imperial city. Furthermore, calligraphy in both Chinese and Arabic writing appears throughout the complex, sometimes exhibiting a fusion of styles called Sini, referring to Arabic text written in Chinese-influenced script. Some scholars also speculate that the three-story, octagonal pagoda in the third courtyard, called the Shengxinlou or “Examining the Heart Tower,” originally served as the mosque's minaret, used for the call to prayer.[3]: 346

The prayer hall is a monumentally sized timber building with a turquoise hip roof, painted dougong (wooden brackets), a six-pillared portico, and five doors. It is raised upon a large stone platform lined with balustrades. The expansive prayer hall consists of three conjoined buildings, set one behind the other. Interior ornamentation is centered on the rear qibla wall, which has wooden carvings of floral and calligraphic designs.

Gallery

-

“Examining the Heart Tower” in the third courtyard

-

Wahbi Al-Hariri's graphite drawing of the Great Mosque of Xi'an

-

Phoenix Pavilion in the fourth courtyard

-

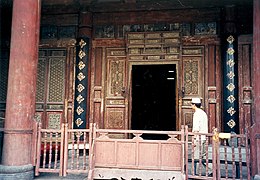

Facing the prayer hall of the Great Mosque of Xi'an, in the fourth courtyard

-

Entrance to the prayer hall

-

Calligraphy on a plaque in the Great Mosque of Xi'an

See also

- Islam in China

- Timeline of Islamic history

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic art

- List of the oldest mosques in the world

- List of famous mosques

- List of mosques in China

References

- ^ Liu, Zhiping (1985). Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu [Islamic architecture in China]. Xinjiang Renmin Chubanshe.

- ^ a b c Steinhardt, Nancy S. (2015). China’s Early Mosques. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748670413.

- ^ Steinhardt, Nancy S. (2008). "China's Earliest Mosques". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 67 (3).