Hawazin

| Hawazin (Arabic: هوازن) | |

|---|---|

| Qaysi/Adnanite/Ishmaelites | |

Ancestry of the Hawazin Tribe | |

| Location | Ancient Arabia |

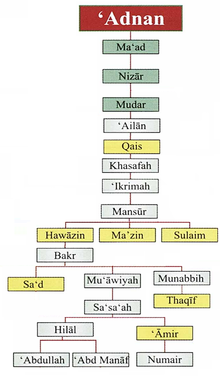

| Descended from | Hawazin ibn Mansur ibn Ikrimah ibn Khasafah ibn Qays ʿAylān ibn Mudar ibn Nizar ibn Ma'add ibn Adnan. |

| Parent tribe | Qays |

| Branches |

|

| Religion | Polytheism (Pre-Islam) Islam (Post Islam) |

The Hawazin (Arabic: هوازن / ALA-LC: Hawāzin) were an ancient Pre-Islamic Arab tribe considered to be the descendants of Hawazin son of Mansur son of Ikrimah son of Khasafah son of Qays ʿAylān son of Mudar son of Nizar son of Ma'ad son of Adnan son of Aa'd son of U'dud son of Sind son of Ya'rub son of Yashjub son of Nabeth son of Qedar son of Ishmael, or Ishmaelites, son of Abraham.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

In the oral tradition and studies on genealogy, the modern-day tribe of Otaibah in the Arabian Peninsula are the de facto descendants of the Hawazin tribe. Based in the Hejaz at the time, they formed part of the larger Qaysi tribal grouping, and were the main Qaysi force that fought the Quraysh and Kinana during the Fijar War in the late 6th century.[9][5][2]

The tribe's defeat at the Hunayn was a factor in enabling Islam to spread beyond Arabia. Upon their surrender and conversion, the tribe was told to choose between reclaiming the women who had been taken captive following the battle and the property that had been taken from them as booty. They chose the women.[10][11]

In the Pre-Islamic era, the foster-mother and wetnurse of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Halimah al-Sa‘diyah, and her husband were from the tribe of the Banu Sa'd, a subdivision of Hawazin.[12][13]

Furthermore, the tribe often clashed with their one-time patrons, the Ghatafan, and on occasion, sub-tribes of the Hawazin fought each other. The tribe had little contact with the Islamic prophet Muhammad until 630 when they were defeated by Muhammad's forces at the Battle of Hunayn. After the battle, Muhammad treated the Hawazin chief Malik ibn 'Awf al-Nasri well. Nevertheless, the Hawazin tribe were one of the one of first to rebel and fight against the religion after the death of Muhammad in the seventh century during the Wars of Apostasy.[14][14][15][16][17][18][19]

The Hawazin were a large group that included the sub-tribes of the Banu Sa'd ibn Bakr ibn Hawazin. The Banu Nasr and the Banu Jusham sons of Mu'awiyah ibn Bakr ibn Hawazin. The Banu Thaqif ibn Munabbih ibn Bakr ibn Hawazin. The Banu 'Amir ibn Sa'sa'ah.[9][20]

Furthermore, the tribe among other tribes were called 'The Great Skulls of Arabia.' The other tribes under the ancient title included the tribe of Kinana, the tribe of Tamim, the tribe of Bakr Ibn Wael, the tribe of Al Aizd, the tribe of Ghatafan, the tribe of Muthehej, the tribe of Abd Al Qays, and the tribe of Guda'a. As the rulers of the land prior to the rise of Islam, the tribes under the title were characterized by strength, abundance, superiority, and honor. The name derived from the notion that the skull is the most important part of the body.[21][22][23][24][25]

Origins and branches

The tribe formed part of the larger Qays Aylan group (also known simply as "Qays"). In the traditional sources, references to the Hawazin were often restricted to certain descendants of the tribe, known as ʿUjz Hawāzin (the rear of Hawazin); these subtribes were the Banu Sa'd, Banu Nasr and Banu Jusham. The founders of these subtribes were either the sons of Bakr ibn Hawazin or the sons of Mu'awiya ibn Bakr ibn Hawazin. Two other major branches of the Hawazin, the Banu 'Amir ibn Sa'sa' and the Banu Thaqif, were often grouped separately from the other Hawazin sub-tribes.[20]

History

Pre-Islamic era

The Hawazin were pastoral nomads that inhabited the steppes between Mecca and Medina.[26] Beginning around 550 CE, the Hawazin became a vassal tribe of the Banu 'Abs of Ghatafan under the 'Absi chieftain Zuhayr ibn Jadhima.[20][27] When the latter was killed by the Banu 'Amir ibn Sa'sa' some years later, the Hawazin discontinued their tribute to Ghatafan.[20][27] Sporadic battles and wars occurred in the following years, often between the bulk of the Hawazin, in alliance with the Banu Sulaym, on one side, and the bulk of the Ghatafan on the other.[20] Less often, there were armed feuds among certain Hawazin subtribes, particularly between the Banu Jusham and Banu Fazara.[20]

During the Fijar War in the late 6th century, the Hawazin and much of the Qays, excluding the Ghatafan but including the Banu 'Amir, Banu Muharib and Banu Sulaym, fought against the Quraysh and Kinana tribes. The war was precipitated by the murder of 'Urwa ibn al-Rahhal of the Banu 'Amir by al-Barrad ibn Qays al-Damri of Kinana while 'Urwa was escorting a Lakhmid caravan from al-Hirah to Ukaz during the holy season; this was considered sacrilegious by the pagan Arabs, hence the war's name, ḥarb al-fijār (the war of sacrilege).[28] This incident occurred amid a trade war between the Quraysh of Mecca and the Banu Thaqif of Ta'if; the latter were both kinsmen and allies of the Hawazin.[20] The war consisted of eight battle days occurring over the span of four years.[28]

After hearing news of 'Urwa's death, the Hawazin pursued al-Barrad's Qurayshi patron Harb ibn Umayya and other Qurayshi chieftains from Ukaz to Nakhla; the Quraysh were defeated, but the chieftains were able to escape to Mecca.[28] The following year, the Hawazin were again victorious against the Quraysh and Kinana at Shamta near Ukaz.[28] The latter became the site of battle during the next year, and the Hawazin once again defeated the same parties.[28] The Quraysh and Kinana defeated the Hawazin at Ukaz or a nearby site called Sharab in the fourth major battle of the Fijar War, but the Hawazin recuperated and landed a blow against the Quraysh in the al-Harrah volcanic fields north of Mecca in the fifth and final significant engagement of the war.[28] Afterward, minor clashes occurred before peace was established.[28]

Islamic era

There was scant contact between the Hawazin and the Islamic prophet Muhammad, who hailed from the Quraysh tribe.[19] However, there were generally good relations with the Banu 'Amir.[19] Also, Muhammad's wet nurse, Halima bint Abu Dhu'ayb, came from the Hawazin subtribe of Banu Sa'd.[19] It was not until Muhammad's victorious entry into Mecca, that the first major encounter between the main body of Hawazin and the Muslims under Muhammad occurred.[19] Muhammad heard that Malik ibn 'Awf of the Banu Nasr was mobilizing a large force of Hawazin and Thaqif tribesmen near Mecca, thus threatening the city and the Muslims, and prompting Muhammad's forces, including a 2,000 Qurayshi tribesmen, to confront Malik's forces at the Battle of Hunayn in 630.[19] During this engagement, the Thaqif managed to escape to Ta'if, but the Hawazin were routed and lost much of their property.[19] However, Muhammad immediately reconciled with the Hawazin by returning Malik's wife and children to him, giving him a gift of camels and recognizing his chieftainship of the Hawazin.[19] The Hawazin had to pay a sum to retrieve their captive women and children.[19]

The Hawazin discontinued the sadaqa (voluntary donation) given to Muslim authorities in Medina following Muhammad's death in 632, and like many other Arab tribes, Hawazin did take part in combat against the successor of Muhammed, Abu Bakr during the Ridda Wars. Hawazin ultimately returned to the Islamic fold by the end of the war.[29][30]

References

- ^ Quran 6:86

- ^ a b H. Kindermann-[C.E. Bosworth]. "'Utayba." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007.

- ^ "The Book of Genesis".

- ^ Al-Qthami, Hmood (1985). North of Hejaz. Jeddah: Dar Al Bayan.

- ^ a b Al Rougi, Hindees. "The Tribe of Otaibah".

- ^ Parolin, Gianluca P. (2009). Citizenship in the Arab World: Kin, Religion and Nation-State. p. 30. ISBN 978-9089640451. "The ‘arabicised or arabicising Arabs’, on the contrary, are believed to be the descendants of Ishmael through Adnan, but in this case the genealogy does not match the Biblical line exactly. The label ‘arabicised’ is due to the belief that Ishmael spoke Hebrew until he got to Mecca, where he married a Yemeni woman and learnt Arabic. Both genealogical lines go back to Sem, son of Noah, but only Adnanites can claim Abraham as their ascendant, and the lineage of Mohammed, the Seal of Prophets (khatim al-anbiya'), can therefore be traced back to Abraham. Contemporary historiography unveiled the lack of inner coherence of this genealogical system and demonstrated that it finds insufficient matching evidence; the distinction between Qahtanites and Adnanites is even believed to be a product of the Umayyad Age, when the war of factions (al-niza al-hizbi) was raging in the young Islamic Empire."

- ^ Reuven Firestone (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. p. 72. ISBN 9780791403310.

- ^ Göran Larsson (2003). Ibn García's Shuʻūbiyya Letter: Ethnic and Theological Tensions in Medieval al-Andalus. p. 170. ISBN 9004127402.

- ^ a b Al-Qthami, Hmood Dawi (1985). North of Hejaz. Jeddah: Dar Al Bayan.

- ^ Lammens, H. and Kamal, ʿAbd al-Hafez, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs (2012). "Ḥunayn", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. ISBN 9789004161214.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarar. The History of al-Tabari Vol. 9: The Last Years of the Prophet. Translated by Ismail K. Poonawala. p. 25-28. ISBN 9780887066917.

- ^ Mubarakpuri, Safiur Rahman (1979). The Sealed Nectar. Saudi Arabia: Dar-us-Salam Publications. p. 56.

- ^ Haykal, Muhammad Husyan (1968). The Life of Muhamad. India: Millat Book Center. p. 47.

- ^ a b Lammens, H. and Abd al-Hafez Kamal. "Hunayn". In P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online Edition. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- ^ "When The Moon Split". Darussalam. 1 July 1998 – via Google Books.

- ^ The sealed nectar, By S.R. Al-Mubarakpuri, Pg356

- ^ Najibabadi, Akbar S. K. HISTORY OF ISLAM - Tr. Atiqur Rehman (3 Vols. Set). Adam Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 9788174354679.

- ^ IslamKotob. Tafsir Ibn Kathir all 10 volumes. IslamKotob.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Watt 1971, p. 286.

- ^ a b c d e f g Watt 1971, p. 285.

- ^ Al Andulsi, Ibn Abd Rabuh (939). Al Aqid Al Fareed.

- ^ Al-Qthami, Hmood (1985). North of Hejaz. Jeddah: Dar Al Bayan. p. 235.

- ^ Ali Phd, Jawad (2001). "A Detailed Account of the History of Arabs Before Islam". Al Madinah Digital Library. Dar Al Saqi.

- ^ Al Zibeedi, Murtathi (1965). Taj Al Aroos min Jawahir Al Qamoos.

- ^ Al Hashimi, Muhammed Ibn Habib Ibn Omaya Ibn Amir (859). Al Mahbar. Beirut: Dar Al Afaaq.

- ^ Donner 2010, p. 95.

- ^ a b Fück 1965, p. 1023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fück 1965, p. 883.

- ^ Donner 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Ibrahim Abed; Peter Hellyer (2001). United Arab Emirates: A New Perspective. Trident Press. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-1-900724-47-0.

Bibliography

- Donner, Fred M. (2010). Muhammad and the Believers, at the Origins of Islam. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6.

- Fück, J. W. (1965). "Fidjār". In Lewis, B; Pellat, Ch; Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 2, C-G (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 883–884. ISBN 90-04-07026-5.

- Fück, J. W. (1965). "Ghatafan". In Lewis, B; Pellat, Ch; Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 2, C-G (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 1023–1024. ISBN 90-04-07026-5.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1971). "Hawāzin". In Lewis, B; Ménage, M. L.; Pellat, Ch; Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 3, H-Iram (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 285–286. ISBN 90-04-08118-6.