History of Ivory Coast

| History of Ivory Coast |

|---|

|

|

|

Human arrival in Ivory Coast (officially called Côte d'Ivoire) has been dated to the Upper Paleolithic period (15,000 to 10,000 BC), or at the minimum, the Neolithic period based on weapon and tool fragments, specifically polished shale axes and remnants of cooking and fishing.[1][2] The earliest known inhabitants of Côte d'Ivoire left traces scattered throughout the territory. Historians believe these people were all either displaced or absorbed by the ancestors of the present inhabitants.[3] Peoples who arrived before the 16th century include the Ehotilé (Aboisso), Kotrowou (Fresco), Zéhiri (Grand Lahou), Ega, and Diès (Divo).[4]

Prehistory and early history

[edit]Little is known about the original inhabitants of Côte d'Ivoire.[3] The first recorded history is in the chronicles of North African Muslims who conducted a caravan trade across the Sahara in salt, slaves, gold, and other items from early Roman times.[3] The southern terminals of the trans-Saharan trade routes were located on the edge of the desert, and from there, supplemental trade extended as far south as the edge of the rainforest.[3] The more important terminals—Djenné, Gao, and Timbuctu—grew into major commercial centers around which the great Sudanic empires developed.[3] These empires dominated neighboring states by controlling the trade routes with powerful military forces.[3]

The Sudanic empires also became centers of Islamic learning.[3] Islam was introduced into western Sudan by Arab traders from North Africa and spread rapidly after the conversion of many important rulers.[3] By the 11th century, the rulers of the Sudan empires had embraced Islam that spread south into the northern areas of contemporary Ivory Coast.[3]

Ghana was the earliest of the Sudan empires; it flourished in present-day eastern Mauritania from the fourth to the 13th century.[3] At the peak of its power in the 11th century, its realms extended from the Atlantic Ocean to Timbuctu.[3] After the decline of Ghana Empire, the Mali Empire grew into a powerful Muslim state, reaching its peak in the early 14th century.[3] The territory of the Mali Empire in Ivory Coast was limited to the northwest corner around Odienné.[3]

The Songhai Empire flourished there between the 14th and 16th centuries.[3] Songhai was weakened by internal discord, leading to factional warfare.[3] This discord spurred the migrations of peoples southward toward the forest belt.[3]

The dense rainforest in the south created barriers to large-scale political organizations like those in the north.[3] In the south, people lived in villages or village clusters whose contacts with the outside world came through long-distance traders.[5] These villagers subsisted on agriculture and hunting.[5]

Pre-European era

[edit]Five important states flourished in Ivory Coast in the pre-European era.[5] The Bono kingdom of Gyaman was established in the 17th century by the Abron, an Akan group that fled the developing Ashanti Empire in Ghana.[6] From their settlement south of Bondoukou, the Abron gradually extended their dominance of the Juula, recent emigrants from the market city of Begho.[6] Bondoukou developed into a major center of commerce and Islam.[6] The kingdom's Quranic scholars attracted students from all parts of West Africa.[6]

In the mid-18th century in east-central Ivory Coast, other Akan groups fleeing the Ashanti Empire established a Baoulé kingdom at Sakasso and two Agni kingdoms, Indénié and Sanwi.[6] The Baoulé, like the Ashanti, elaborated a highly centralized political and administrative structure under three successive rulers, but it finally split into smaller chiefdoms.[6] Despite the breakup of their kingdom, the Baoulé strongly resisted French subjugation.[6] The descendants of the rulers of the Agni kingdoms tried to retain their separate identity long after Ivory Coast's independence; as late as 1969, the Sanwi of Krinjabo attempted to break away from Ivory Coast and form an independent kingdom.[6]

In the early 18th century, the Juula established the Muslim Kong Empire in the north-central region inhabited by the Sénoufo, who fled Islamization under the Mali Empire.[5] The Kong Empire was a prosperous center of agriculture, trade, and crafts but weakened gradually because of ethnic diversity and religious discord.[6] The city of Kong was destroyed in 1895 by Samori Touré.[6]

Trade with Europe and the Americas

[edit]Because of its location between Europe and the imagined treasures of the Far East, Africa became a destination for the European explorers of the 15th century.[6] The first Europeans to explore the West African coast were the Portuguese.[6] Other European sea powers followed and established trade with many of the coastal peoples of West Africa.[6] At first, trade included gold, ivory, and pepper but the establishment of American colonies in the 16th century spurred demand for slaves.[6] This led to the kidnapping and enslaving of people from the West African coastal regions for transportation to North and South America (see African slave trade).[6] Local rulers obtained goods and slaves from the inhabitants of the interior to fulfill treaties with the Europeans.[6] By the end of the 15th century, trade with the Europeans had resulted in a strong European influence in Africa, permeating north from the West African coast.[6]

Ivory Coast, like the rest of West Africa, was subject to these influences but the absence of sheltered harbors along its coastline prevented Europeans from establishing permanent trading posts.[6] Thus, seaborne trade was irregular and played only a minor role in the penetration and eventual conquest of Ivory Coast by Europeans.[7] The slave trade, in particular, had little effect on the peoples of Ivory Coast.[7] A profitable trade in ivory existed in the 17th century and gave the area its name.[7] However, the resulting decline in elephant population ended the ivory trade by the beginning of the 18th century.[7]

The earliest recorded French voyage to West Africa was in 1483.[7] The French founded their first West African settlement, Saint Louis, in the mid-17th century in what is now Senegal; around this time, the Dutch ceded a settlement at Ile de Gorée to the French.[7] The French established a mission in 1687 at Assinie, near the Gold Coast (now Ghana) border, and it became the first European outpost in that area.[7] Although Assini's survival was precarious, the French did not establish themselves in Ivory Coast until the mid-19th century.[7] By that time, the French had settlements around the mouth of the Senegal River and at other points along the coasts of Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau.[7] Meanwhile, the British had permanent outposts in the same areas and on the Gulf of Guinea, east of Ivory Coast.[7]

In the 18th century, Ivory Coast was invaded by two related Akan groups—the Agni, who occupied the southeast, and the Baoulés, who settled in the central section. In 1843–1844, the French admiral Bouët-Willaumez signed treaties with the kings of the Grand Bassam and Assini regions, placing these territories under a French protectorate. French explorers, missionaries, trading companies, and soldiers gradually extended the area under French control inland from the lagoon region.[8]

Activity along the coast stimulated European interest in the interior, especially along Senegal and Niger rivers.[7] French exploration of West Africa began in the mid-19th century but moved slowly and was based more on individual initiative than government policy.[7] In the 1840s, the French concluded a series of treaties with local West African rulers, enabling the French to build fortified posts along the Gulf of Guinea to serve as permanent trading centers.[7] The first posts in Ivory Coast were at Assinie and Grand-Bassam, which became the colony's first capital.[7] The treaties gave the French sovereignty for trading privileges in exchange for fees or customs paid annually to the local rulers for the use of their land.[7] This arrangement was not entirely satisfactory to the French because trade was limited and misunderstandings over treaty obligations often arose.[7] Nevertheless, the French government maintained the treaties, hoping to expand trade.[7] France also wanted to maintain a presence in the region to limit the growing influence of the British along the Gulf of Guinea coast.[7]

The defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War (1871) and the subsequent annexation of the French province of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany caused the French government to abandon its colonial ambitions and withdraw its military garrisons from its West African trading posts, leaving them in the care of resident merchants.[7] The trading post at Grand-Bassam was left to Arthur Verdier, a shipper from Marseille who was named a resident minister when the Ivory Coast was established in 1878.[9]

In 1885, France and Germany brought the European powers with interests in Africa together at the Berlin Conference. The conference helped rationalize what became known as the European scramble for Africa.[10] Prince Otto von Bismarck also wanted a greater role in Africa for Germany, which he thought he could achieve in part by fostering competition between France and Britain.[10] The agreement signed by all conference participants in 1885 stipulated that on the African coastline, only European annexations or spheres of influence that involved effective occupation by Europeans would be recognized.[10] Another agreement in 1890 extended this rule to the interior of Africa and resulted in a rush for territory by France, Britain, Portugal, and Belgium.[10]

Establishment of French rule

[edit]

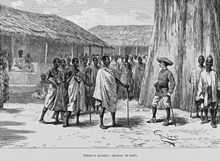

To support its claims of effective occupation, France again assumed direct control of its West African coastal trading posts and embarked on an accelerated program of exploration in the interior in 1886.[10] In 1887, Lieutenant Louis Gustave Binger began a two-year journey across Ivory Coast's interior.[11] By the end of his journey, Binger had secured four treaties that established French protectorates in Ivory Coast.[11] Also in 1887, Verdier's agent, Marcel Treich-Laplène, negotiated five additional agreements that extended French influence from the headwaters of the Niger River Basin through Ivory Coast.[11] By the end of the 1880s, France had established effective control over the coastal regions of Ivory Coast and Britain recognized French sovereignty in the area in 1889.[11] France named Treich-Laplène the titular governor of the territory in 1889.[11] In 1893, Ivory Coast was made a French colony; agreements with Liberia in 1892 and with Britain in 1893 determined the eastern and western boundaries of the colony, but the northern boundary was not fixed until 1947 when the French government wanted to attach parts of Upper Volta (present-day Burkina Faso) and French Sudan (present-day Mali) to Ivory Coast for economic and administrative reasons.[11]

Throughout the process of partition, the Africans were little concerned with the occasional European who came wandering by.[11] Many local rulers of small, isolated communities did not understand or, more often, were misled by the French about the significance of treaties that compromised their authority.[11] However, other local leaders thought that the French could solve economic problems or become allies in the event of a dispute with belligerent neighbors.[11] In the end, the loss of sovereignty by the local rulers was often the result of their inability to counter French deception and military force, rather than a result of support for French encroachment.[11]

French colonial era

[edit]

Colony of Ivory Coast Colonie de Côte d'Ivoire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1893–1960 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Grand-Bassam (1893–1896); Bingerville (1896–1934); Abidjan (1934–1960) | ||||||||

| Government | French colony | ||||||||

| President of France | |||||||||

• 1893–1894 | Sadi Carnot | ||||||||

• 1959–1960 | Charles de Gaulle | ||||||||

| Colonial governor | |||||||||

• 1893–1895 | Louis-Gustave Binger (first) | ||||||||

• 1960 | Yves Guéna (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism, First World War, Interwar period, Second World War, Decolonisation of Africa, Cold War | ||||||||

• Côte d'Ivoire officially becomes a French colony | 10 March 1893 | ||||||||

• Accession to French West Africa | 1904 | ||||||||

• Ivory Coast becomes an autonomous republic within the French Community | December 1958 | ||||||||

• Independence from France | 7 August 1960 | ||||||||

| Currency | French West African franc (1903–1945); West African CFA franc (1945–1960) (XOF) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Côte d'Ivoire officially became a French colony on 10 March 1893.[12] Louis Gustave Binger who had explored the Gold Coast frontier, was named the first governor.[12][11] He negotiated boundary treaties with Liberia and Britain (for the Gold Coast).[12] Throughout the early years of French rule, French military contingents went inland to establish new posts.[11] The French settlements encountered resistance from locals, even in areas with treaties of protection.[11] Samori Touré offered the greatest resistance; he had established the Wassoulou Empire over large parts of present-day Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast starting in 1878.[11] Tourés large, well-equipped army could manufacture and repair its own firearms, attracting strong support throughout the region.[11] Binger responded to Touré's expansion of regional control with military pressure, resulting in fierce resistance.[11] The French campaigns against the Wassoulou intensified in the mid-1890s until they captured Touré in 1898.[11]

In 1900, France imposed a head tax for a public works program in the colony, provoking several revolts.[13] The public works programs and the related exploitation of natural resources required a huge workforce.[14] The French imposed a system of forced labor, requiring each adult male Ivorian to work ten days each year without compensation as an obligation to the state.[14] This system was subject to extreme misuse and was the most hated aspect of French colonial rule by the Africans.[14] Because the population of Ivory Coast was insufficient to meet the labor demands of French-held plantations and forests, the greatest users of labor in French West Africa, the French recruited large numbers of workers from Upper Volta to Ivory Coast.[14] The forced labor was not only disadvantageous to the men forced to work but also to the Ivorian farmers as well. As farming gained importance to the economic growth of Ivory Coast, European and African farmers alike worked diligently to enlarge their businesses. This inherently caused a need for more workers, a need far greater than the number of workers available. During this time, amidst World War II, the French government systematically gave worker preference to the European farmers and made the African farmers find voluntary workers locally or close up shop entirely. These systemic injustices caused great strife between the African working class as they were growing further apart from their European counterparts and had little to no say in the matter as none of them were recognized, French citizens.[15] This labor source was so important to the economic life of Ivory Coast that in 1932 the AOF annexed a large part of Upper Volta to Ivory Coast and administered it as a single colony.[14] Many Ivorians viewed the head tax as a violation of the terms of the protectorate treaties because it seemed that France was now demanding a coutume or payment from the local kings rather than the reverse.[13] Much of the population, especially in the interior, considered the tax a humiliating symbol of submission.[13]

From 1904 to 1958, Ivory Coast was a constituent unit of the Federation of French West Africa. It was a colony and an overseas territory under the Third Republic. Until the period following World War II, governmental affairs in French West Africa were administered from Paris. France's policy in West Africa was reflected mainly in its philosophy of "association", meaning that all Africans in Ivory Coast were officially French subjects without rights to representation in Africa or France. In 1905, the French officially abolished slavery in most of French West Africa.[16]

In 1908, Gabriel Angoulvant was appointed governor of Ivory Coast.[13] Angoulvant had little prior experience in Africa but believed that the development of Ivory Coast could proceed only after the forceful conquest, or so-called pacification, of the colony.[13] He sent military expeditions into the hinterland to quell resistance.[13] As a result of these expeditions, local rulers were compelled to obey existing antislavery laws, supply porters and food to the French forces, and ensure the protection of French trade and personnel.[13] In return, the French agreed to leave local customs intact and specifically promised not to intervene in the selection of rulers.[13] However, the French often disregarded their side of the agreement, deporting or interning rulers seen as instigators of revolt.[13] They also regrouped villages and established a uniform administration throughout most of the colony.[13] Finally, they replaced the coutume system with an allowance based on performance.[17]

French colonial policy incorporated concepts of assimilation and association.[17] Assimilation presupposed the inherent superiority of French culture over all others; the assimilation policy in the colony meant the extension of the French language, institutions, laws, and customs.[17] The policy of association not only affirmed the superiority of the French but also entailed different institutions and systems of laws for the colonizer and the colonized.[17] Under this policy, the Africans in Ivory Coast were allowed to preserve their customs insofar as they were compatible with French interests.[17] An indigenous elite trained in French administrative practice formed an intermediary group between the French and the Africans.[17]

Assimilation was practiced in Ivory Coast to the extent that a small number of Westernised Ivorians were granted the right to apply for French citizenship after 1930.[17] However, most Ivorians were classified as French subjects with no political rights under the principle of association.[17][14] Moreover, they were drafted for work in mines, on plantations, as porters, and on public projects as part of their tax responsibility.[14] They were also expected to serve in the military and were subject to the indigénat, a separate system of laws for Africans.[14]

In World War II, the Vichy regime remained in control until 1943, when members of General Charles De Gaulle's provisional government assumed control of all French West Africa. The Brazzaville conference in 1944, the first Constituent Assembly of the Fourth Republic in 1946, and France's gratitude for African loyalty during World War II led to far-reaching governmental reforms in 1946. French citizenship was granted to all African "subjects," the right to organize politically was recognized, and various forms of forced labor were abolished. A turning point in relations with France was reached with the 1956 Overseas Reform Act or Loi-cadre Defferre, which transferred several powers from Paris to elected territorial governments in French West Africa and also removed remaining voting inequalities.[18]

Until 1958, governors appointed in Paris administered the colony of Ivory Coast, using a system of direct, centralized administration that left little room for Ivorian participation in policymaking.[17] The French colonial administration also adopted divide-and-rule policies, applying ideas of assimilation only to the educated elite.[17] The French were interested in ensuring that the small but influential elite was sufficiently satisfied with the status quo to refrain from any anti-French sentiment.[17] Although strongly opposed to the practices of association, educated Ivorians believed that they would achieve equality with their French peers through assimilation rather than through complete independence from France, a change that would eliminate the enormous economic advantages of remaining a French possession.[17] After postwar reforms, the Ivorian leaders realized that assimilation implied the superiority of the French over the Ivorians and that discrimination and inequality would end only with independence.[17]

Independence

[edit]As early as 1944, Charles de Gaulle proposed to change France's politics and take "the road of a new era."[19] In 1946, the French Empire was converted into the French Union which was superseded by the French Community in 1958.[19] In December 1958, Ivory Coast became an autonomous republic within the French Community as a result of a referendum on 7 August that brought community status to all members of the old Federation of French West Africa (except Guinea, which had voted against the association). On 11 July 1960, France agreed to Ivory Coast becoming fully independent.[19][20] Ivory Coast became independent on 7 August 1960, and permitted its community members to lapse. It established the commercial city Abidjan as its capital.

Ivory Coast's contemporary political history is closely associated with the career of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, president of the republic and leader of the Democratic Party of Ivory Coast (PDCI) until his death on 7 December 1993. He was one of the founders of the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA), the leading pre-independence inter-territorial political party for all of the French West African territories except Mauritania.

Houphouët-Boigny first came to political prominence in 1944 as the founder of the African Agricultural Union, an organization that won improved conditions for African farmers and formed a nucleus for the PDCI. After World War II, he was elected by a narrow margin to the first Constituent Assembly. Representing Ivory Coast in the French National Assembly from 1946 to 1959, he devoted much of his effort to inter-territorial political organization and further amelioration of labor conditions. After his thirteen years in the French National Assembly, including almost three years as a minister in the French Government, he became Ivory Coast's first prime minister in April 1959, and the following year was elected its first president.

In May 1959, Houphouët-Boigny reinforced his position as a dominant figure in West Africa by leading Ivory Coast, Niger, Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), and Dahomey (Benin) into the Council of the Entente, a regional organization promoting economic development. He maintained that the road to African solidarity was through step-by-step economic and political cooperation, recognizing the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other African states.

Houphouët-Boigny was considerably more conservative than most African leaders of the post-colonial period, maintaining close ties to the West and rejecting the leftist and anti-western stance of many leaders at the time. This contributed to the country's economic and political stability. The first multiparty presidential elections were held in October 1990 and Houphouët-Boigny won convincingly. He died on 7 December 1993.

After Houphouët-Boigny

[edit]Houphouët-Boigny was succeeded by his deputy Henri Konan Bédié, President of the Parliament. Konan Bédié was 24 December 1999, during the 1999 Ivorian coup d'état by General Robert Guéï, a former army commander who was dismissed by Bédié. This was the first coup d'état in the history of Ivory Coast. An economic downturn followed and the junta promised to return the country to democratic rule in 2000.

Guéï allowed elections to be held the following year. When he lost the election to Laurent Gbagbo, Gué at first refused to accept his defeat. However, street protests forced him to step down, and Gbagbo became president on 26 October 2000.

First Civil War

[edit]On 19 September 2002, a rebellion in the north and the west of Ivory Coast flared up and the country was divided into three parts. Mass murders occurred, notably in Abidjan from 25 to 27 March, when government forces killed more than 200 protesters, and on 20 and 21 June in Bouaké and Korhogo, where purges led to the execution of more than 100 people. In 2002, France sent troops to Ivory Coast as peacekeepers. A reconciliation process under international auspices started in 2003. In February 2004, the United Nations established the United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (UNOCI)

Disarmament was supposed to take place on 15 October 2004, but was a failure. Tensions between Ivory Coast and France increased on 6 November 2004, after Ivorian air strikes killed 9 French peacekeepers and an aid worker.[21] In response, French forces attacked the airport at Yamoussoukro, destroying all airplanes in the Ivorian Air Force. Violent protests erupted in both Abidjan and Yamoussoukro and were marked by violence between Ivorians and French peacekeepers.[22] Thousands of foreigners, especially French nationals, evacuated the two cities. Most of the fighting ended by late 2004, with the country, split between a rebel-held north under the leadership of Guillaume Soro and a government-held south under the leadership of Laurent Gbagbo.

Under this system, the quality of life dropped overall, with an increase in debt and civil unrest. To answer these problems, the concept of "ivoirité" was born, a racist term targeted denying political and economic rights to the Northern immigrants. In March 2007 the two sides signed an agreement to hold fresh elections. However, the elections were delayed until 2010, five years after Gbagbo's term of office expired.

Second Civil War

[edit]After northern candidate Alassane Ouattara was declared the victor of the 2010 Ivorian presidential election by the country's Independent Electoral Commission (CEI), the President of the Constitutional Council and an ally of Gbagbo, declared the results to be invalid and that Gbagbo was the winner. Both Gbagbo and Ouattara claimed victory and took the presidential oath of office. The international community, including the United Nations, the African Union, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the European Union, the United States, and former colonial power France affirmed their support for Ouattara and called for Gbagbo to step down. However, negotiations to resolve the dispute failed to achieve any satisfactory outcome. Hundreds of people died in escalating violence between pro-Gbagbo and pro-Ouattara partisans and at least a million people fled, mostly from Abidjan.

International organizations reported numerous instances of human rights violations by both sides, particularly in Duékoué. The United Nations and French forces took military action to protect their forces and civilians. Ouattara's forces arrested Gbagbo at his residence on 11 April 2011.[23]

After the 2011 Civil War

[edit]Alassane Ouattara has ruled Ivory Coast since 2010, when he unseated his predecessor Laurent Gbagbo. Ouattara was re-elected in 2015 presidential election.[24] In November 2020, he won a third term in the 2020 presidential election. His opponents boycotted the election, arguing that a third term was illegal.[25] Ivory Coast's Constitutional Council formally ratified Ouattara's re-election to a third term in November 2020.[26]

See also

[edit]- History of Africa

- History of West Africa

- List of heads of government of Ivory Coast

- List of heads of state of Ivory Coast

- Politics of Ivory Coast

- Abidjan history and timeline

References

[edit]- ^ Guédé, François Yiodé (1995), "Contribution à l'étude du paléolithique de la Côte d'Ivoire : État des connaissances" (PDF), Journal des Africanistes (in French), 65 (2): 79–91, doi:10.3406/jafr.1995.2432, ISSN 0399-0346, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Rougerie, Gabriel (1978), L'Encyclopédie générale de la Côte d'Ivoire (in French), Abidjan: Nouvelles publishers africaines, p. 246, ISBN 978-2-7236-0542-7, OCLC 5727980

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Rougerie, Gabriel (1978), L'Encyclopédie générale de la Côte d'Ivoire (in French), Abidjan: Nouvelles publishers africaines, p. 5, ISBN 978-2-7236-0542-7, OCLC 5727980

- ^ Kipré, Pierre (1992), Histoire de la Côte d'Ivoire (in French), Abidjan: Editions AMI, pp. 15–16, OCLC 33233462

- ^ a b c d Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 6. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 7. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 8. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 3. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 8–9. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ a b c d e Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 9. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 10. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ a b c "What Changed the Ivory Coast from an Example of Economic Development Into a Bloodbath". Docslib. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 11. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ a b c d e f g h Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 14. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Murphy, D. (1 January 2008). "French Colonialism Unmasked: The Vichy Years in French West Africa". French Studies. 62 (1): 112–113. doi:10.1093/fs/knm287. ISSN 0016-1128.

- ^ "Slave Emancipation and the Expansion of Islam, 1905–1914 Archived 2013-05-02 at the Wayback Machine". p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Handloff, Robert Earl, ed. (1988). Cote d'Ivoire: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 12. OCLC 44238009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ "France: The "Loi-Cadre" of June 23, 1956 | Internet History Sourcebooks". Fordham University. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "1960: The year of independence". France 24. 14 February 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "4 African States Attain Freedom; France Gives Independence to Ivory Coast, Niger, Dahomey, and Volta". New York Times. 12 July 1960.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (7 November 2004). "Ivory Coast Violence Flares; 9 French and 1 U.S. Death". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Carroll, Rory; correspondent, Africa; Henley, Jon (8 November 2004). "French attack sparks riots in Ivory Coast". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

{{cite news}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ "Ivory Coast's Laurent Gbagbo arrested – four months on". TheGuardian.com. 11 April 2011.

- ^ "Ivory Coast's Ouattara re-elected by a landslide". Al Jazeera. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Ivory Coast election: Alassane Ouattara wins amid boycott". BBC News. 3 November 2020.

- ^ "Ivory Coast Constitutional Council confirms Ouattara re-election". Al Jazeera. 9 November 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Chafer, Tony. The End of Empire in French West Africa: France's Successful Decolonization. Berg (2002). ISBN 1-85973-557-6