History of Hawaii

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Hawaii |

|---|

| Topics |

The history of Hawaii includes both natural and human history. After the creation of the islands by volcanic forces, the islands began developing their flora and fauna. Sometime around 1 AD, the earliest Polynesian settlers began to populate the islands. Around 1200 AD Tahitian explorers found and began settling the area as well. This became the rise of the Hawaiian civilization and would be separated from the rest of the world for another 500 years until the arrival of the British. Within five years of contact with Great Britain, a single ruler would conquer a majority of the islands for the first time in its human history. The Kingdom of Hawaii would become important for its agriculture and strategic location in the pacific. Euro-American immigration began almost immediately after contact by Captain Cook. American style, plantation farming required extensive labor. Several waves of workers immigrated from China and Japan in large numbers. Eventually the Hawaiian monarchy would be overthrown after outside business interests organized against the kingdom through the legislature, weakening the King's rule. After the coup d'état a brief period would see a Republic of Hawaii organized by the same forces that took the islands and led to annexation as a territory and then as the state of Hawaii within the United States.

Discovery and settlement

The earliest settlements in the Hawaiian Islands are generally believed to have been made by Polynesians who reached Hawaii using large double-hulled canoes. They brought with them pigs, dogs, chickens, taro, sweet potatoes, coconut, banana, sugarcane, and other plants and animals.

Several theories describe migration to Hawaii. The "one-migration" theory suggests a single settlement. A variation on the one-migration theory instead suggests a single, continuous settlement period. Several "multiple migration" theories exist. One variation suggests that the original migration could have been followed by settlers from the Marquesas Islands, and then later by Tahitians.

Numerous accounts describe possible landings by Europeans, Chinese and others long before the arrival of Captain Cook; however, none have been documented with certainty.

On January 18, 1778 British Captain James Cook and his crew, while attempting to discover the Northwest Passage between England and Asia, encountered the islands and were surprised to find a Polynesian island so far north in the Pacific.[1] He named them the "Sandwich Islands", after the fourth Earl of Sandwich. Members of this expedition described the population of the islands as abundant, handsome and healthy. Unfortunately the British brought many new infectious diseases to the islands, in particular tuberculosis and venereal diseases that quickly propagated through the locals.[2]

In 1786, seven years after Cook, a French frigate arrived in Hawai'i and reported that most of the islanders were very sick. By 1832 only 130,000 remained.[2]

Kingdom of Hawaii

Formation of the Hawaiian Kingdom

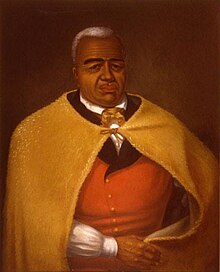

Kamehameha I united the islands into a single kingdom for the first time in 1810 with the help of foreign weapons and advisors. The monarchy adopted a flag similar to the one used as the present flag of the State of Hawaii, with the Union Flag in the canton (top quarter next to the flagpole) and eight horizontal stripes (alternating white, red, blue, from the top), representing the eight major islands.

In May 1819, Prince Liholiho became King Kamehameha II. Under pressure from his co-regent and stepmother, Kaʻahumanu, he abolished the kapu system that had ruled life in the islands. He signaled this revolutionary change by sitting down to eat with Kaʻahumanu and other women of chiefly rank, an act forbidden under the old system—see ʻAi Noa. Kekuaokalani, a cousin who thought he was to share power with Liholiho, organized supporters of the kapu system, but his forces were defeated by Kaʻahumanu and Liholiho in December 1819 at the battle of Kuamoʻo.[3]

France

In the early kingdom, Protestant ministers convinced Kamehameha I to make Catholicism illegal, deport French priests and imprison Native Hawaiian Catholic converts.

In 1839 Captain Laplace of the French frigate Artémise sailed to Hawaii. Under the threat of war, King Kamehameha III signed the Edict of Toleration on July 17, 1839 and paid $20,000 in compensation for the deportation of the priests and the incarceration and torture of converts, agreeing to Laplace's demands. The kingdom proclaimed:

That the Catholic worship be declared free, throughout all the dominions subject to the king of the Sandwich Islands; the members of this religious faith shall enjoy in them the privileges granted to Protestants.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu returned and Kamehameha III donated land for them to build a church as reparation.

In August 1849, French admiral Louis Tromelin arrived in Honolulu Harbor with his ships La Poursuivante and Gassendi. De Tromelin made ten demands to King Kamehameha III on August 22, mainly that full religious rights be given to Catholics (Catholics still enjoyed only partial religious rights). On August 25 the demands had not been met. After a second warning, French troops overwhelmed the skeleton force and captured Honolulu Fort, spiked the coastal guns and destroyed all other weapons they found (mainly muskets and ammunition). They raided government and other property in Honolulu, causing $100,000 in damages. After the raids the invasion force withdrew to the fort. De Tromelin eventually recalled his men and left Hawaii on September 5.

Great Britain

On February 10, 1843, Lord George Paulet on the Royal Navy warship HMS Carysfort entered Honolulu Harbor and demanded that King Kamehameha III cede the Hawaiian Islands to the British Crown. Under the guns of the frigate, Kamehameha stepped down under protest.[4] Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25,

- Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands?'

- Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified.

- Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843.

- Kamehameha III.

- Kekauluohi.[5]

Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the Minister of Finance, secretly sent envoys to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet's actions.[6]

The protest was forwarded to Rear Admiral Richard Darton Thomas, Paulet's commanding officer, who arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843 on HMS Dublin. Thomas repudiated Paulet's actions, and on July 31, 1843, restored the Hawaiian government. In his restoration speech, Kamehameha declared "Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono", the motto of the future State of Hawaii translated as "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness."

Kamehameha family

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family ended in 1873 after the death of Kamehameha V and a short reign of Lunalilo. The House of Kalākaua came to the throne next. These transitions were by election of candidates of noble birth.

United States

American Protestant missionaries settled in Hawaiʻi at the beginning of the 19th century and quickly gained influence and wealth. They prohibited local traditions they disliked, like hula or surfboarding. Reverend Amos Starr Cooke, who arrived in 1837, set up a school to educate the future monarchs. When one of his pupils rose to the throne, Cooke was appointed unofficial adviser to the king in 1843 and from this position devised a land reform that allowed foreigners to purchase land from locals in order to plant sugarcane. Cooke and other missionaries became big landowners and sugar producers, and got control of the economy.[2]

The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 between the Kingdom of Hawaii (explicitly acknowledged as a sovereign nation) and the United States allowed for duty-free importation of Hawaiian sugar into the United States beginning in 1876. This further promoted plantation agriculture, which was in the hands of foreign Whites. Hawai'i ceded Pearl Harbor, including Ford Island (Template:Lang-haw), together with its shoreline and four to five miles of land adjacent to the shore, free of cost to the U.S.[7] The U. S. demanded this area based on an 1873 report commissioned by the U. S. Secretary of War. Native Hawaiians protested the treaty on the streets until the revolt was suffocated by U.S. marines.[2]

The treaty also included duty-free importation of rice, which was by this time becoming a major crop in the abandoned taro patches in the wetter parts of the islands. This led to an influx of immigrants from Asia (first Chinese, and later Japanese) needed to support the escalating sugar industry and provided the impetus for expansion of rice cultivation. Water needed for growing sugarcane resulted in extensive water works to divert streams from the wet windward slopes to the dry lowlands.

Overthrow of the Kingdom

In the late 19th century the dominant White minority overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom and founded a brief Republic that was finally annexed by the United States.

Bayonet Constitution and Wilcox Rebellions

In 1887 members of the American white minority, which held most of the important government positions by that time, founded the Reform Party (also known as the Missionary Party) and an armed militia, the Honolulu Rifles.[2] That same year, the Honolulu Rifles and a group of cabinet officials and advisors to King David Kalākaua seized the royal palace and forced the king to promulgate what is known as the Bayonet Constitution. The impetus was the frustration of the Reform Party with growing debts, the King's spending habits and general governance. It was specifically triggered by a failed attempt by Kalākaua to create a Polynesian Federation and accusations of an opium bribery scandal.[note 1][9] The 1887 constitution stripped the monarchy of much of its authority, imposed significant income and property requirements for voting, and completely disenfranchised all Asians.[8]: 20 Three fourths of the votes were assigned to whites, which included all American residents thanks to a special rule from the U.S. State Department.[2]

Native Hawaiians felt the 1887 constitution was imposed by the foreign population because of the king's refusal to renew the Reciprocity Treaty. The treaty now included an amendment to permit the US Navy to establish a permanent naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oʻahu. According to bills submitted by the King, foreign policy would include an alliance with Japan and supported other countries he perceived to be suffering from colonialism. Many Native Hawaiians opposed a US military presence in their country.

A plot by Princess Liliʻuokalani was exposed to overthrow King David Kalākaua in a military coup in 1888. In 1889, a rebellion of Native Hawaiians led by Colonel Robert Wilcox attempted to replace the unpopular Bayonet Constitution and stormed ʻIolani Palace. The rebellion, known as the Wilcox rebellions, was crushed by the Honolulu Rifles.

When Kalākaua died in 1891 during a visit to San Francisco, his sister Liliʻuokalani ascended the throne. Queen Liliʻuokalani called her brother's reign "a golden age materially for Hawaii".[10]

1893

According to Queen Liliʻuokalani, immediately upon ascending the throne, she received petitions from two-thirds of her subjects and the major Native Hawaiian political party in parliament, Hui Kalaiʻaina, asking her to proclaim a new constitution. Liliʻuokalani drafted a new constitution that would restore the monarchy's authority and the suffrage requirements of the 1887 constitution.

In response to Liliʻuokalani's suspected actions, a group of European and American residents formed a Committee of Safety on January 14, 1893. After a meeting of supporters, the Committee committed itself to removing the Queen and annexation to the United States.[11]

United States Government Minister John L. Stevens summoned a company of uniformed US Marines from the USS Boston and two companies of US sailors to land and take up positions at the US Legation, Consulate and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893. The Committee of Safety had claimed an "imminent threat to American lives and property".[note 2]

The Provisional Government of Hawaii was established, led by Sanford Dole, to manage the Hawaiian islands between the overthrow and expected annexation, supported by the Honolulu Rifles White militia group.

Under this pressure, Liliʻuokalani abdicated her throne. The Queen's statement yielding authority, on January 17, 1893, pleaded for justice:

- I Liliʻuokalani, by the Grace of God and under the Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the Constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a Provisional Government of and for this Kingdom.

- That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the Provisional Government.

- Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

The Provisional Government sent members of the Missionary Party to Washington to negotiate the annexation treaty, which was signed on February 14, 1893. President Benjamin Harrison, who had just lost the presidential elections, promptly submitted it to the Senate for ratification but then an envoy from the deposed Queen arrived in Washington and made the case that the dethroning and annexation were illegal.[2] Senators opposed the ratification of the treaty and president-elect Grover Cleveland commissioned an investigation into the events of the overthrow that was conducted by former Congressman James Henderson Blount. The Blount Report was completed on July 17, 1893 and concluded that "United States diplomatic and military representatives had abused their authority and were responsible for the change in government."[12] In the meantime the Leper War on Kauaʻi was suppressed by Provisional Government troops.

Minister Stevens was recalled, and the commander of military forces in Hawaii was forced to resign. Cleveland stated "Substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair the monarchy." Cleveland further stated in his 1893 State of the Union Address[13] and that, "Upon the facts developed it seemed to me the only honorable course for our Government to pursue was to undo the wrong that had been done by those representing us and to restore as far as practicable the status existing at the time of our forcible intervention." Submitting the matter to Congress on December 18, 1893, after provisional President Sanford Dole refused to reinstate the Queen on Cleveland's command, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under chairman John Morgan continued investigation into the matter.

On February 26, 1894, the Morgan Report was submitted, contradicting the Blount Report and finding Stevens and the US troops "not guilty" of any involvement in the overthrow. The report asserted that, "The complaint by Liliʻuokalani in the protest that she sent to the President of the United States and dated the 18th day of January, is not, in the opinion of the committee, well founded in fact or in justice."[14] After submission of the Morgan Report, Cleveland ended any efforts to reinstate the monarchy, and commenced diplomatic relations with the new government. He rebuffed further entreaties from the Queen to intervene.

Republic of Hawaii

Fears grew among the Hawaiian Whites of a US intervention to restore the kingdom. A Constitutional Convention began on May 30, 1894 and the Republic of Hawaii was declared on July 4, 1894, American Independence Day, under the presidency of Sanford Dole.

In the 1895 Counter-Revolution, a group led by Colonel Robert Nowlein, Minister Joseph Nawahi, members of the Royal Household Guards and later Robert Wilcox, attempted to overthrow the Republic. The leaders including Liliʻuokalani were captured, convicted, and imprisoned.

American territory

Annexation to the United States

In March 1897, William McKinley succeeded Cleveland as President. He agreed to a treaty of annexation but it was not approved by the Senate because petitions from the islands indicated lack of popular support. A joint resolution was written by Congressman Francis G. Newlands to annex Hawaii.

In 1897 the Empire of Japan sent warships to Hawaii to oppose annexation.[15]

McKinley signed the Newlands Resolution which annexed Hawaii, illegally in the opinion of annexation opponents, on July 7, 1898 creating the Territory of Hawaii. On 22 February 1900 the Hawaiian Organic Act established a territorial government. He appointed Dole as territorial governor. The territorial legislature convened for the first time on February 20, 1901. Hawaiians formed the Hawaiian Independent Party, under the leadership of Robert Wilcox, Hawaii's first congressional delegate.

Plantation era

| Hawaii's Big Five |

|---|

Sugar plantations in Hawaii expanded during the territorial period. Some of the companies diversified and came to dominate related industries including transportation, banking and real estate. Economic and political power was concentrated in what were known as the "Big Five" corporations.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor was attacked on 7 December 1941 by the Empire of Japan, triggering the United States' entry into World War II. Most Americans had never heard of Pearl Harbor, even though it had been used by the US Navy since the Spanish–American War. Hawaii was put under martial law until the end of the war.

Democratic Party

In 1954 a nonviolent revolution of industry-wide strikes, protests and other civil disobedience transpired. In the territorial elections of 1954 the reign of the Hawaii Republican Party in the legislature came to an abrupt end, replaced by the Democratic Party of Hawaii. Democrats lobbied for statehood and gained the governorship from 1962 to 2002. The Revolution also unionized the labor force, hastening the decline of the plantations.

Statehood

President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Hawaii Admission Act on March 18, 1959 which allowed for Hawaiian statehood. After a popular referendum in which over 93% voted in favor of statehood, Hawaii was admitted as the 50th state on August 21, 1959.

Sovereignty movements

For many Native Hawaiians, the manner in which Hawaii became a US territory is a bitter part of its history. Hawaii Territory governors and judges were direct political appointees of the US president. Native Hawaiians created the Home Rule Party and seek greater self-government. Hawaii was subject to cultural and societal repression during the territorial period and the first decade of statehood. Along with other self-determination movements worldwide the 1960s Hawaiian Renaissance led to the rebirth of Hawaiian language, culture and identity.

With the support of Hawaii Senators Daniel Inouye and Daniel Akaka, Congress passed a joint resolution called the "Apology Resolution" (US Public Law 103-150). It was signed by President Bill Clinton on November 23, 1993. This resolution apologized "to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893... and the deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination." The implications of this resolution have been extensively debated.[16][17]

Akaka proposed what is called the Akaka Bill to extend federal recognition to those of Native Hawaiian ancestry as a sovereign group similar to Native American tribes.[18]

See also

- List of conflicts in Hawaii

- List of Missionaries to Hawaii

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hawaii

- Timeline of Honolulu

Notes

References

- ^ Paul Capper. "Chronology: The Third Voyage (1776-1780)". The Captain Cook Society. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bradley, James (2009). The Imperial Cruise: a secret history of empire and war. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 148–162. ISBN 978-0-316-00895-2.

- ^ Seaton, S. Lee (Feb 1974). "The Hawaiian "kapu" Abolition of 1819". American Ethnologist. 1 (1): 193–206. doi:10.1525/ae.1974.1.1.02a00100.

- ^ "The US Navy and Hawaii--A Historical Summary". Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "The Morgan Report, p500-503". Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "La Ku'ko'a: Events Leading to Independence Day, November 28, 1843". Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Ford Island History — Hawaii Aviation". Hawaii.gov. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ a b c William Adam Russ (1992) [1959]. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 0-945636-43-1.

- ^ Ernest Andrade, Jr. (1996). The Unconquerable Rebel. University Press of Colorado. pp. 42–44. ISBN 0-87081-417-6. "The opium scandal and fragmentary news concerning the Samoan embassy led to unprecedented criticism and unrest by a political opposition that had by this time gone far beyond venting its dissatisfaction through political action."

- ^ Liliʻuokalani (Queen of Hawaii) (July 25, 2007) [1898]. Hawaii's story by Hawaii's queen, Liliuokalani. Lee and Shepard, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2.

- ^ The Morgan Report, p817 "There was talk at the meeting of the committee at W.R. Castle's, on the next (Sunday) morning, of having resolutions abrogating the monarchy and pronouncing for annexation, offered at the mass meeting;"

- ^ Ball, Milner S. (1979). "Symposium: Native American Law". Georgia Law Review. 28: 303.

- ^ "Grover Cleveland, State of the Union Address, 1893". Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Reports of Committee on Foreign Relations 1789-1901 Volume 6 (The Morgan Report), p385". Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Morgan (2011). Pacific Gibraltar: U.S.-Japanese rivalry over the annexation of Hawaiʻi, 1885-1898. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-529-5.

- ^ Carolyn Lucas (December 30, 2004). "Law expert Francis Boyle urges natives to take back Hawaii". West Hawaii Today. Archived from the original on 2005-01-02. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fein, Bruce (June 6, 2005). "Hawaii Divided Against Itself Cannot Stand". Angelfire on Lycos. Waltham, MA, USA: Lycos. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Aloha, Apartheid: A court strikes down a race-based policy in Hawaii, while Congress considers enshrining one". Wall Street Journal. August 8, 2005.

Further reading

- Daws, Gavan (1968). Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-0324-8.

- Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1965) [1938]. Hawaiian Kingdom 1778-1854, foundation and transformation. Vol. Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1953). Hawaiian Kingdom 1854-1874, twenty critical years. Vol. Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1967). Hawaiian Kingdom 1874-1893, the Kalakaua Dynasty. Vol. Volume 3. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Vowell, Sarah. Unfamiliar Fishes, Riverhead, New York, 2011. (Covers 1820-1898)

External links

- Audio of Dwight D. Eisenhower Hawaii Statehood Proclamation Speech

- Public Law 103-150

- Scots in Hawai`i

- How Spain Cast Its Spell On Hawai'i, by Chris Cook in The Islander Magazine

- History of Hawaii: The Pokiki: Portuguese Traditions in The Islander Magazine

- Today in Hawai`i History

- "Russians in Hawai`i". Hawaii History Community Learning Center. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- "The French in Hawai`i". Hawaii History Community Learning Center. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- "Significant Dates in the History of Hawaiʻi". Hawaiian Historical Society. Retrieved November 12, 2014.